The SNES Classic Mk. II: Episode V: Isometric Exercise, Care To Join Me?

By Mento 0 Comments

The SNES Classic had a sterling assortment of games from Nintendo's 16-bit star console, but it's hardly all that system has to offer a modern audience. In each installment of this fortnightly feature, I judge two games for their suitability for a Classic successor based on four criteria, with the ultimate goal of assembling another collection of 25 SNES games that not only shine as brightly as those in the first SNES Classic, but have equally stood the test of time. The rules, list of games considered so far, and links to previous episodes can all be found at The SNES Classic Mk II Intro and Contents.

Episode V: Isometric Exercise, Care To Join Me?

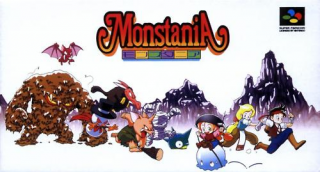

The Candidate: Bits Laboratory's Monstania

We have a couple of isometric bangers this week, as a distinctive visual format that actually saw a decent amount of use on the SNES; being a British gamer of a certain age, I'm more acquainted with what is also known as "3/4 view" due to older Rare games like Sabre Wulf, but the Japanese were fond of it also: it was because of a game Artdink created, A-Train III, that caused the isometric perspective to briefly take over the SimCity franchise for a while. It's very common in strategy RPGs also, which brings us to this week's candidate game: Monstania, from Bits Laboratory.

If you've not heard of the developer Bits Laboratory before, don't worry: they were a fairly obscure company that mostly worked with corporations like Bandai to produce forgettable anime license games. They also worked with Square for some of their lesser NES titles, like Thexder and King's Knight, and Masaya for a few of their weird-as-hell Cho Aniki shoot 'em ups. Of their few wholly original games, however, Monstania stands tall as a both an imaginative and mostly future-proof SNES game: exactly what we're after here on the SNES Classic Mk. II.

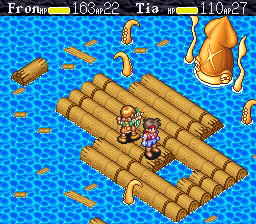

Monstania begins with the adventurer couple Fron and Tia chasing a floating ball of light into a nearby patch of forest. Fron has been looking for fairies since he was a child, and Tia mostly just tags along to ensure he doesn't get too badly hurt. The plot builds from there, with the duo befriending a young fairy named Chitta as they head around the world to foil the plans of a couple of moustache-twirling villains, one SRPG map at a time. However, beyond the isometric and grid-based movement, Monstania is streamlined in many ways that makes it almost unrecognizable when compared to its many peers on the system, like the comparatively more traditional Bahamut Lagoon, Front Mission or Tactics Ogre. For one, you only ever have two characters active for any map, and while characters only act in turns it's more like a roguelike with the simultaneous movement of your characters and the enemy side - some enemies can even move twice for every one of your turns, while others are slow enough that you can move twice for one of theirs. It gets crazier: your characters don't have separate turns, but instead the player can move either of them, even the same one multiple times consecutively. The "resting" character instead replenishes some of their action points, used for special attacks and spells. The player can choose to skip both characters' turn by having them stand still, which also replenishes action points. Characters can spend zero points to either team-up or separate, the former means that both move simultaneously in procession for each turn, but spreading out also comes with a wealth of tactical options. It should also be noted that there's barely any menus: you only need to bring them up to use a technique or an item, and the rest of the time you use the D-pad and face buttons to perform standard actions like movement, attacking, or waiting a turn.

This structural novelty also extends to the battles themselves, which rarely repeat themselves. This is partly due to how short the game is - you're unlikely to see more than forty battles in a single playthrough, and they all move relatively fast given the small group of playable characters - but it offers everything from solo combat, team combat, boss fights, stealth sequences, puzzle sequences, escort sequences, fights where you're trying to escape a rolling ball trap (which is always kinda weird in a turn-based game), fights where you need to survive endless waves for a fixed duration, and - oddly enough - at least one set of puzzles where you have to cross every space on the map without touching the same spot twice. It fits a lot into its slight frame, and its many guest characters and enemy types offer a wide variety. That said, the difficulty curve is all over the place, but usually errs towards the easy side - the enemy AI is fairly bad so characters can endlessly regenerate their action points by waiting it out a sufficient distance away, which allows them to recover all their lost health via cheap cure spells, and the game is generous with its heal-all consumables to boot - and the game runs out of new abilities to give the heroes after the game's halfway point. The fan localization is a bit... well, I actually enjoyed it, but there's some strange word choices which you can see in the screenshots below. I think Aeon Genesis, which has translated a lot of SFC games in the past, had a bit more fun with this game's script than was perhaps warranted. But hey, that just makes the game all that more unique and fun.

- Preservation: A lot of what I've been doing with this feature, in what is perhaps a case of serendipity, is finding what were regarded as flawed games at the time and discovering that those flaws have aged into positives, as the demands of a fickle audience have shifted over time. In Monstania's case, you could point to a few elements - it has a relatively complex movement system that's unlike its contemporaries, it's very short and its battles move lightning fast, and it's intended for a younger audience and yet is filled with unusual little asides and phrase choices - and see an ugly duckling that has since matured into a swan. 4.

- Originality: I assumed it would be "SRPGs for babies" territory, but Monstania's structure and progression has rendered it a singular example of the genre, albeit a not particularly replayable one. The combination of SRPG group combat and roguelike simultaneous movement isn't something I've seen too often - in fact, the only examples coming to mind are Vandal Hearts II and the Frozen Synapse games - and the multitude of options that its unusual list of abilities provides offer far more versatility than you'd perhaps ever need. I'd say that fan translation is pretty original too, for better or worse. 4.

- Gameplay: Though brief, it really puts its engine through as many concepts as the designers could devise, such as the stealth sequences, puzzles, and trap escapes mentioned previously. I've also mentioned the game's tactical versatility, where you can fight as a melee character several turns in a row while your healer slowly regenerates their spell points to keep that melee in the fight, or sacrifice some of their own to allow the melee character to heal themselves. That said, as a pure SRPG it has about three or four truly difficult encounters and the rest are a breeze: its not balanced particularly well, and some guest characters are better developed than others. 3.

- Style: I'm a big fan of the isometric perspective in video games, and the characters and monsters in Monstania all have detailed and expressive sprites that suit their characterization. There's a certain Secret of Mana vibe to the main trio - boy, girl, and sprite - and to the overall cuteness level of the world. The backgrounds and scenes have less to distinguish themselves, unfortunately. However, the music is uniformly excellent, thanks to composer Noriyuki Iwadare; he's better known for his work with the Grandia and Lunar franchises. (Curiously, the portraits look like Harvest Moon characters - that game's developer, Amccus, provided some design work to this game also.) 3.

Total: 14.

Other images:

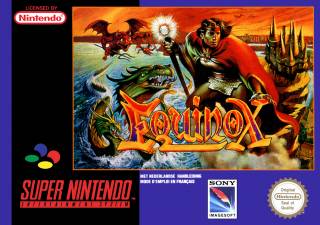

The Nominee: Software Creations's Equinox

The United Kingdom isn't generally a country that comes to mind when you think of hotbeds of game development for the 16-bit era of consoles. In the early 90s the UK largely stayed loyal to the Commodore Amiga and Atari ST platforms (both of which were actually American computers, but let's not split hairs), and occasionally one or more of those games would find their way onto the SNES and Genesis via some manner of cultural osmosis: those considered big enough to be released in wider distribution, like Populous, Lemmings, Cannon Fodder, and so on. Beyond the few odd times when a UK developer was risen up to major prominence by Nintendo itself - as was the case for Rare's Donkey Kong Country franchise or Argonaut Games's support crafting the polygons in Star Fox and Star Fox 2 - console-exclusive games from the UK were few and far between, and actually good ones were rarer still.

Which is why Software Creations's Equinox (and another game of theirs to come much later) holds a special place in my heart. It wasn't just a "local" SNES game, but one of the system's best, abandoned in obscurity in part due to its European roots and niche appeal. The direct sequel to the NES game Solstice (it even refers to itself as Solstince II during its intro) Equinox was the last big hurrah for the isometric puzzle action-adventure game: those that emphasized open-world exploration seen more commonly in games like Super Metroid, along with puzzle-solving and difficult combat challenges that required you to evade and pick your moment to strike. It also has a healthy dose of weirdness, both with its overall vibe of an Arabian adventurer fighting giant naked trolls, floating demonic skulls, colorful Pac-Man ghosts and more, and with the sublime ambient soundtrack provided by musical maestros Tim and Geoff Follin. The Follins pushed the SNES's S-SMP sound chip to places it had never seen before or has since, and beyond an incongruously hard-pounding boss theme and the rousing intro music, most of the game's soundtrack was comprised entirely of an eerie ambience that establishes the game's tone (and leisurely pace) so perfectly.

In pure mechanical terms, the game is separated into multiple dungeons, each one blocked off until a boss has been defeated. These dungeons have multiple entrances and contain twelve glowing dark orbs: by finding all twelve and bringing them to a specific room, you can summon and subsequently destroy the boss of that zone and move onto the next. Each dungeon also has a new weapon and a new magic spell - sometimes better hidden than the summon orbs - and once per level you can increase your maximum health by defeating gigantic overworld enemies. Dungeons get progressively harder, and the isometric perspective can sometimes create some visual confusion - is a platform on the ground at the back, or floating in the air closer to the camera? - but overall, the unhurried exploration (aided in no small amount by the chill soundtrack) and frequent influx of new platforming and puzzle-solving challenges keeps the game fresh until the end.

- Preservation: I still submit that games that use the isometric perspective, especially in the context of an action game rather than a sim or SRPG, are rare enough that they haven't aged as badly as some other retro games. The two major causes for a game to age like Donovan (not that one) at the end of The Last Crusade is that they either come from a genre popular enough to have been iterated upon so often that the genre has effectively evolved into something unrecognizable, or the technology behind them has progressed to the point of leaving them feeling antiquated by comparison. Equinox's charms are as potent today as they've ever been - we wouldn't have had 2016's Lumo if there wasn't some steam in that very specific, very British format. 3.

- Originality: It all depends on how you contextualize a game's distinctiveness. If we're taking into account the various games that Rare's made over the years, as well as Equinox's NES predecessor Solstice and games like Monster Max for the Game Boy, it doesn't quite stand out as much. If we're just talking the SNES library, it's practically unique - and that's taking into account that the SNES/SFC has something like 1,700 games. 4.

- Gameplay: Equinox can be a bit too challenging for its own good at times, between the aforementioned visual confusion and some limited air control when jumping, but for the most part its mix of platforming, exploration, and combat puts it somewhere in the region of a Zelda game - you aren't going to conquer those dungeons without putting in the work of figuring them out and maybe making a mental map of where you still need to go and what keys and doors you've found so far. For an action game, it's surprisingly contemplative, and not one you can expect to rush through without injury. 4.

- Style: Graphically, the game is a little garish - I think the developers were a little too beholden to the gaudy neon colors of the game's ZX Spectrum spiritual ancestors. The main character looks like a goofy weirdo with a permanent cocky expression, except during the brief interstitial scenes whenever he enters a dungeon in which he looks far more human, and the enemies - besides bosses - have fairly generic, cartoony designs. If there's no remarkable style to be seen, there's plenty to be heard. Like I've said, the Follins really were on a whole different level than most SNES composers. 3.

Total: 14.

Other images: