Rediscovering the mysteries beyond the sea

By nateandrews 3 Comments

"I came to this place to build the impossible. You came to rob what you could never build. A Hun, gaping at the gates of Rome. Even the air you breathe is sponged from my account. Well, breathe deep ... so later you might remember the taste.”

Often I think that exploring the mysteries of a piece of fiction, be it a video game, a film, or novel, is only an excellent experience the first time through. Perhaps my most damningly disappointing example involves my second watch of 2001: A Space Odyssey, a film that had me utterly transfixed on every beat of its weird, orchestral heart, but that on a second viewing felt more like watching a sort of languid dream version of what I thought I remember the film being. Is it still one of my favorites? Absolutely. Will I watch it a third time? That's a trickier question.

Bioshock is a game that I played through quite a number of times back in the day. But with the dawn of the current generation of consoles I left Rapture behind, having successfully collected every audio diary, explored every cranny (and all the nooks, too), and even completed the whole thing on Hard without using those Vita-Chambers. It's a testament to how much BioShock's wonderfully imaginative world and inspired story grabbed me that I was able to play through it as many times as I did, but I was unsure how it would feel going back to it now after so many years, this time as part of the Bioshock Collection.

BioShock has always been a collection of moments for me, both large and small, narrative and gameplay-related. All of these contribute to how positively alien the city of Rapture feels, so hopelessly lost in its grandest ambitions that it was blind to all of the lesser vices, hiccups, and other flaws that together would prove fatal to the society's structural integrity. All the chain metaphors in the world couldn't save Andrew Ryan's utopia from the pitfalls of faction rivalry, rampant drug addiction, and poverty. If leaking pipes and ceilings in a city underwater is the least of someone's problems, something has gone terribly wrong. What's amazing is that rediscovering Rapture and its numerous failures is just as enthralling as it was the first go-around, in large part because those moments still hit so well.

A Buckshot Ballet

One of my favorite moments occurs early on in BioShock, in the Medical Pavilion. It's time to get a shotgun, a supremely satisfying weapon that's... actually not that great on Hard. But for about 30 seconds after picking the shotgun up, it's the best gun in the world.

With BioShock, Irrational Games sought to give players a chance to use new weapons and Plasmids immediately after acquiring them. This particular shotgun is located in a dimly lit room next to a bloody corpse illuminated by a fallen sign. A case of buckshot next to it helpfully indicates that the weapon is ready to go, which is nice because the lights immediately go out after grabbing it. Following a bit of maniacal laughter and the pattering of footsteps, a spotlight shines down on the center of the room and a murderous dance of gunfire and bodies begins. Splicers attack from all sides, running in from the shadows to beat Jack into the ground. But Jack has a shotgun.

You can use Plasmids and the Pistol here, but that would be missing the point. Jack has a shotgun, and it absolutely flattens the attacking Splicers. In any other game, this moment of player empowerment happening at a time when Jack is supposed to be in over his head would feel out of place. But the Splicers planned this exact moment, knowing full well that Jack would be equipped with a weapon so devastating in close quarters the Germans protested its use in the First World War. And thus it becomes clear that the wanton casting away of human lives is the order of the day in Rapture.

It's worth mentioning too just how entertaining Splicers are as Jack's primary opponent. They're absolutely crazy and completely fearless of both death and the embarrassment of someone eavesdropping on their inane conversations with themselves. They sing, complain, and rant, usually to no one in particular. They're unbelievable fun to mess with in combat. A single hit with the Enrage Plasmid will turn a Splicer against his or her compatriots; if a Big Daddy wanders into the scene and catches the wrath of the Enraged Splicer, a comically one-sided affair unfolds. It's ridiculous.

It’s What You Don’t See

One of my favorite tricks in games is having things in the environment change when the player looks away. BioShock isn’t quite a horror game, but it gets some decent mileage out of changing things behind your back to spook you. There’s a great one late in the game, when exploring an optional flooded room that has some treasure in the back corner. The room has a bunch of discarded mannequins standing about when you enter, but when you pick up the loot in the corner some of these mannequins are replaced with motionless Splicers. If you don’t notice the change, like myself, you’ll get a good jump from the upcoming ambush.

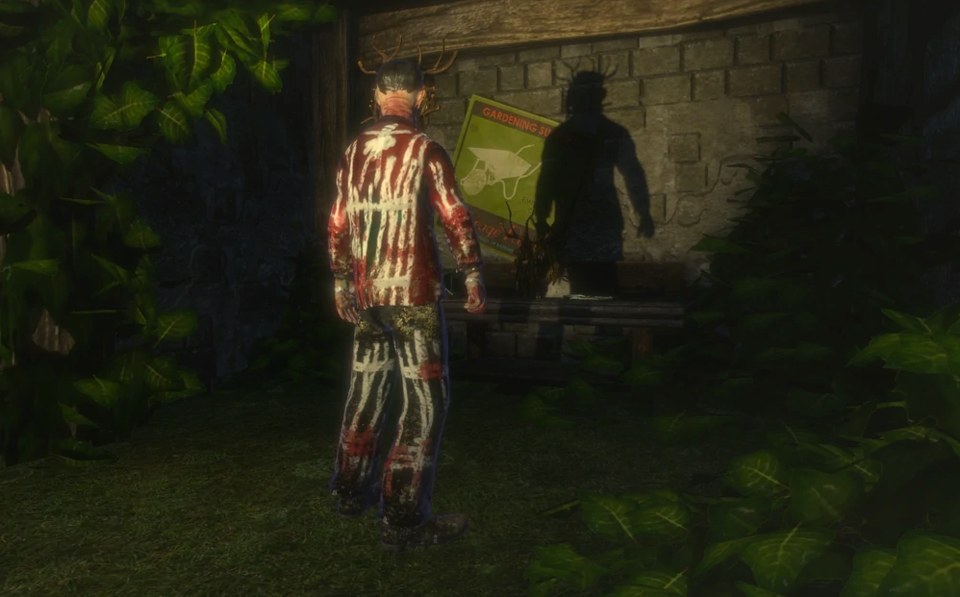

My personal favorite occurs in Arcadia, an arboretum in Rapture that acts as an oxygen supply for the city. A Houdini Splicer tempts you to chase after him through a twisting passageway beneath creaking floorboards. Eventually you come to a table with some money on it, where the light flickers and his silhouette unexpectedly appears on the wall. Turning around reveals the Splicer standing just a foot away, who then remarks, “Hello beautiful!” before vanishing.

BioShock has plenty of exciting scraps with groups of hostiles, but this scene manages to pull off a terrific and powerful encounter with just a single enemy. I get a kick out of reading how other players reacted to it, especially the ones who walked away to take a smoke break.

Sander Cohen's Masterpiece

“Ohh, I can smell the malt vinegar in this one…"

After following the instructions of the affable silver-tongued Atlas for a few hours, having spent just enough time to get accustomed to the way of life in the big city, an enormous curveball is thrown and the bathysphere that's supposed to take Jack to the next level suddenly descends into the sea. Moldy, bleach white human figures rise up on both sides of the platform as if presenting the grand opening of an extraordinary event about to take place. At center stage, a colossal rabbit mask ascends in place of the bathysphere. A man comes over the radio, having successfully jammed Atlas' transmissions. It's time for a show.

Sander Cohen is to art what the mad Dr. Steinman, encountered early in the game, is to medicine. Though he may have been a paint-and-canvas artist early in his career, Cohen’s creative method as encountered in BioShock is more closely related to human experimentation than anything else. Killing his own students is his way of dishing out punishment for poor performance. And those papier-mâché-looking figures found around Fort Frolic are in fact human corpses set up in various poses, a fact you wouldn’t actually know unless you took a swing at one with a wrench and saw the blood.

Jack is given the task of killing several of Cohen’s students and taking a photograph of each corpse to display in the artist’s latest masterpiece. These encounters take Jack all around Fort Frolic and serve as miniature boss fights. Regardless of the ambitions or egos of these pupils, they all end up sharing the same fate: corpses in murky, sepia-toned photos adorning the quadriptych of a madman.

Cohen belittles Jack frequently during his stay at Fort Frolic, calling him “little moth” in between outbursts of rage against his haters. In a particularly memorable moment, after installing the third photograph Cohen suddenly screams out his disdain for the doubters before unleashing a group of Splicers to attack while Waltz of the Flowers plays over loudspeakers. “Fly away, little moth!” he shouts to Jack who, in a moment similar to the shotgun ambush, finds himself dancing around enemies in a spotlight trying to avoid having a death soundtracked by Tchaikovsky. It’s a moment so passionately absurd you might find yourself believing in the joy of this particular brand of destructive chaos if only for a moment.

Upon the completion of the masterpiece, the artist himself makes an appearance, descending a grand staircase to canned applause and confetti. He thanks Jack for his help in the endeavor, restores communications with Altas, and unlocks the way forward. You can actually kill Cohen here and take a picture of his corpse to unlock a trophy/achievement called Irony, or let him live. In a terrific coda to his depraved existence, he can be fought and killed later on by attacking two dancing Splicers in his apartment.

In a game full of characters pushing the limits of their own sanity, Sander Cohen is perhaps the most far-gone of them all. To have no choice but to play by his rules, with no chance of contacting anyone outside of his domain, makes this entire section of BioShock absolutely unforgettable.

Dear Diary, Etc

In the years since BioShock, countless games have deployed audio logs as a means to supplement narratives with the expository musings of various characters, both major and minor. Curiously, I can’t think of any game that has done it quite as well the first BioShock, which I’d also put above the other two entries in the series. Of course, no matter how you slice it the placement of these audio diaries in the environment, and the improbability that they’d still be there intact, is completely ludicrous. But that’s beside the point.

BioShock's audio diaries, aside from being terrifically well-written and acted, allow the player to follow the stories of side characters in addition to fleshing out important scientific, social, political, and economic elements of the city. Diana McClintock leaves a trail of entries detailing the fall of Rapture as it happened and her own transformation in its aftermath. Another series involves a couple trying to find their daughter, who has become a Little Sister. There are entries from scheming businessmen and mechanics, as well as from major players like Andrew Ryan and Yi Suchong discussing their own work and philosophies.

This kind of a narrative delivery mechanism became a sort of running joke due to its increasing prevalence in games, but I’ll always appreciate BioShock's diaries for being as compelling as they are.

Andrew Ryan is Here to Ask You a Question

“Before the final rat has eaten the last gram of you, Rapture will have returned. I will lead a parade. "Who was that," they'll say, as they point to the sad shape hanging on my wall, "who was that?”

"I'd explain the science that renders what you're trying to do impossible, but that would be like playing Mozart for a tree frog.”

"Imagine the will it took to create a place like this. And what have you built? Nothing, you can only loot and break. You're not a man... you're just a termite at Versailles.”

In truth, it’s unlikely much else needs to be said about Andrew Ryan. But as I continue to play games that fail to make their villains compelling, I’m drawn back to this particularly ill-fated visionary time and time again.

The BioShock games love grand ideas and the people who embody them. A great deal of Ryan’s success as the big bad is in part due to his unwavering commitment to his ideals, no matter how flawed. But it’s also in the way he carries himself, in his use of language to expound on the significance of his vision and to denigrate those who would seek to undermine it. He’s an absolute quote machine, especially when Jack begins closing in late in the game and his insults and threats become even more pointed and creative.

The climactic confrontation with Ryan really sells his legacy. His death-by-9-iron lacks the sort of finality one might expect from the killing of a cult of personality figurehead. His final moments aren't even spent fighting for his prized creation; instead he's hitting some golf balls in his office. Ryan achieved what he had set out to do, and though Frank Fontaine may have gotten the better of him in the end, he still built a city under the sea, just as he said he would. He goes to his death knowing that no one else will achieve a similar feat, and likely gains a bit of satisfaction from the fact. After all, it's Jack and Fontaine who are now stuck in the confines of his creation, a fact they'll never forget.

Even now as I write this there's a pull that I feel to jump back into BioShock yet again, to experience everything it has and to marvel at what the team at Irrational was able to craft. It not only changed how I think about narrative in games, it instilled in me the importance of the many worlds and characters that fiction creates and how crucial it is for these things to be well-realized. Of all the games I wish I could experience again for the first time, it's likely that BioShock tops the list. But unlike other mysteries, where some of the magic wears off once you know the secrets, BioShock's allure never quite fades.

"Rapture is coming back to life. Even now, can't you hear the breath returning to her lung? The shops reopening, the schools humming with the thoughts of young minds? My city will live. My city will thrive. And, when that day comes, we'll use your tombstone for paving tiles."