Reflections on the thought-provoking Opera Omnia

By RagingLion 2 Comments

I wanted to write a little about a free indie game called Opera Omnia that I played recently because it does a number of unique or unusual things that are worth thinking about. It's certainly provoked an awful lot of thought in my own head during and after playing it at the very least.

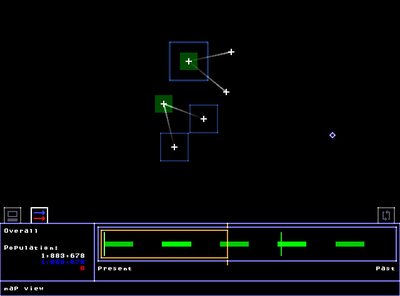

In brief, this is game in which you play a young historian who examines a number of historical scenarios and by positing when migrations took place between different cities over the course of time, tries to demonstrate how the populations of different peoples has fluctuated in the past, sometimes being influenced by famine or war. Each of these scenarios are explored after a conversation with another individual, who largely provides the historical scenarios you are meant to be investigating. So the pattern of the game is of 20 sections where your character and this other guy have a chat resulting in you playing around with various migration routes till the population shift matches up with the starting conditions that you are provided with. You then 'Submit your thesis', have a brief summing up with the other character and move on to the next section. It's worth pointing out that this is all done with very basic graphics and the interface for plotting these migration routes is fairly abstract although perfectly sufficient for showing the population shifts over time.

And that very nature of what this game is about and its subject matter is the first thing of note. This is a game about being a historian. The core gameplay is about plotting migration routes. I love it for having this unique set-up, not that it is superior to any other but it is so thoroughly different and refreshing to inhabit such a niche role and I want games to explore a greater depth of roles and scenarios than they currently do.

That's the nature of the mechanics, but that in itself isn't what's interesting. From this point onwards I'm not sure if everything that I'm inferring was intended by Increpare, the game's creator, but all of the following are thoughts that I feel are being provoked by the game's design as I experienced it. For each section's task you are given these sets of conditions for what the overall population or the population of certain cities should exceed or be less than at the earliest point in the timeline. However, as you mess around with different possible migration routes it became clear to me that the population at the earliest point in the timeline could vary wildly depending on if large amounts of people were in a city during a time of famine or not. There's not always a convincing justification for why you are theorising migration routes at certain times and in certain places. All that seems to matter is that you meet these initial starting conditions, which themselves seem questionable having been provided by the other character who you learn fairly early on is a senior politician in your fictional nation. For a scenario in which a known large population in the past has now been reduced to a far smaller one it seemed presumptuous to simply assume that starvation was the only possible cause (though that's the only option you have to work with in the game). Surely that explanation could just as easily be covering up some kind of mass genocide that had occurred in history. You are praised by the politician for the work you submit in your theses and yet I always had the uneasiness that I hadn't really done anything other than somewhat arbitrarily drawn migration routes onto a map. My character on screen though was clearly thrilled to be producing such important work and enamoured by his position as historian.

Thus, a large part of the game for me was trying to ascertain the true motivations and thoughts of both my character and the politician's. At one point the historian pronounces that his job is 'not to make predictions or establish causality', just to submit the evidence of what occurred plainly it would seem and yet this seemed at odds with the arbitrariness of the mechanics. Things develop as you learn of the existence of the Others, another nation who is supposedly hostile in nature, and has been to your nation in the past, although you seem to be living in relative peace with just some racially motivated rioting in a few cities. I was fully anticipating the two game protagonists to be fully against the Others once they were first mentioned in the narrative and then to falsify history to the ends of their/your own nation ... well yes, that kind of does happen, but it's more nuanced than that. The politician even stands up for the Others at one stage and says they're not as war-like as the majority of your nation considers them to be and that that's all just rumour and yet you then go on to have 2 of the most blatant sections that expose motivations of the characters. One involves claiming the world's greatest artist as your own rather than belonging to the Others by showing that the town he was brought up in originally belonged (could have belonged?) to your people. Then you also manipulate another scenario to suggest that the Others appeared out of nowhere, rather than always belonging on the earth like your people by just playing around with the stats cleverly. Politics meeting history it would seem. That seems to be a point that the game is making. The weird, but also very interesting thing, is that your character the historian seems to implicitly believe everything he is 'proving' is the reality of the past. The very character you are semi-inhabiting is one that I felt pushed away from as I was unable to see eye-to-eye with the interpretations he was bringing to bear on the scenarios he was examining. It's the very opposite of a game such as Half Life (that eternal example in discussing games) where Valve openly state that they make Gordon Freeman a silent protagonist so that the player can fully inhabit the character without feeling distanced by Freeman potentially speaking dialogue that doesn't mesh with what the player would say at that time. The final underlining of my suspicions about the narrow-sightedness and virtual brainwashing of the historian came with the last section where you are now questioning the historian at some point in the distant future and discover that The Others had been almost wiped out in a war that you had already seen was brewing previously. In a city that was in the midst of starvation you only see the numbers of The Others fall while your nation grows slowly. That simple graphic was quite touching and horrifying. It is immediately clear what that represents by this stage of the game. The historian says that many of his people had died in the war and yet it is clear that those numbers were nothing compared to those of the Others and he simply rejoices in the prosperity that it brought for his own nation. He also claims that he had nothing to do with the war although the implication is clearly that his own work was used as propoganda tools to unite his own nation and undermine the history of the Others.

So yeah, that's pretty unusual and thought-provoking. It raises subject matter that is practically unheard of for a game. I don't feel like it particularly changed any beliefs I hold but the power of games is to immerse you in the perspective of another and even with the limited graphics and text-based narrative, this game was still able to achieve that for me and that's a powerful thing.