Cohen Edenfield writes games and plays them. You can find them on Twitter, Twitch, and Youtube. They have a Master’s degree in literature in a landfill somewhere.

I played more games than usual in 2021, just like I did in 2020, for the extremely obvious reason that we’re living in what threatens to be a forever-plague. Desperate as I was for distraction, it seems strange to judge games for how “good” they were. Any game that got me to stop thinking about the circumstances of our shared existence for longer than a few minutes gets a 10/10 from me. I was an easy A.

That caveat aside, some discrete elements of the new games I played this year have managed to stick in my head for weeks and even months after I put them down. My list is an attempt to explore and examine these things. Some of them impressed me, some delighted me, and some of them pissed me off, but they’re all still on my mind. Given the state of my mind these days, that’s quite the accomplishment.

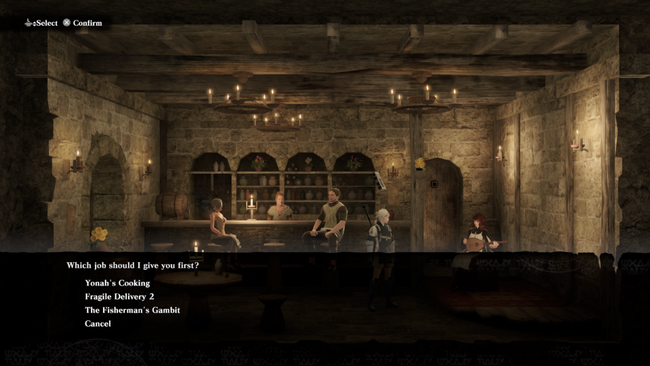

Nier: Replicant Ver. 1.22’s intentional tedium

Nier Automata is a 2017 Yoko Taro game I connected with on a “Matrix plug that goes into the back of my head” level. Everything about its melancholic, decaying world drew me in. And the questions it asked! What, exactly, constitutes a post-apocalypse? If the world ends so hard that only steel and concrete survive, but so much time passes that another world grows up around it, is it still the post-apocalypse? Aren’t we living in the post-apocalypse of the Aztecs, the ancient Greeks, the Neanderthals? What is a robot? What is a soul? Does the steppy robot lady have an Onlyfans? What is a person? Provocative stuff!

When I finished Automata, I started looking into its 2010 predecessor, Nier, and quickly found out I’d need an Xbox 360 to play it in English. Since mine was freezing in a storage unit on the other side of the country, I gave up hope… until this year! Remakes, baby! Everything old is new again, and that includes video games that are boring on purpose. If you make it through this list, you’ll see I’m not easily bored. Nier: Replicant Ver. 1.22 sees my infinite patience and responds “we’ll fucking see.”

Nier: Replicant Ver. 1.22 is stuffed with intentionally tedious, repetitive sidequests, ostensibly as a criticism of other games stuffed with tedious, repetitive sidequests. Most of them are simple fetch quests where the only difficulty comes from travelling across the enormous, empty landscape, occasionally harried by easily-defeated shadow creatures (fast travel is limited, and only becomes available in the second half of the game, at which point the player is locked out of completing most of the sidequests). As you complete these errands, a pedantic living book bobs along in the air behind you, mocking you for your easily-exploited altruism. The rewards for completing these quests are largely useless: weapons that are usually weaker than those you already have, or gold to buy more useless weapons. Some of the quest-givers do mix things up by requiring a large number of rare-drop materials or by requiring you to kill a monster that has an extremely low chance of even appearing.

And yet! And yet! I did all of them. There’s something very interesting about a game that is up-front about being intentionally boring. The stories the sidequests tell are surprisingly affecting, and the game’s frequent acknowledgement of the tediousness of completion, initially frustrating, begins to feel like encouragement to continue. “I know it sucks, but stick with this. I’m making a point here.” There’s intentional tedium and frustration in a lot of the main story, too. At the time, I kind of hated it. But now, half a year later, I think it was great? Maybe that’s the point being made? Is life a series of arbitrary obligations, loosely chained together by a vague sense of purpose that can only be glimpsed in hindsight? I can’t say, since I still have to beat the entire second half of the game several more times to see the rest of the story. I’ll circle back on this next year.

Magic the Gathering: Arena’s excellent tutorial

2021 saw the release of the Adventures in the Forgotten Realms set of Magic: The Gathering. I saw friends posting pictures of the lands, which come with little D&D-appropriate story hooks.

I had a half-formed idea of using them in D&D – I figured I’d get my players to draw from a stack of them, then send them through a hole in reality to briefly participate in the combat/story beat implied by the text. I went to my local game store (hey, The Deck Box!), got some Adventures in the Forgotten Realms booster packs, and, on a whim, also picked up Planar Portal, a preconstructed Commander deck in the AFR set. Flipping through it, I was entranced by the complex strategies implied by the interaction of the cards. Vaxxed to the gills and looking to make more friends in a new city, I decided to attend the store’s “Casual Commander” night. I didn’t actually know how to play Magic, but that seemed like a minor hurdle. I just needed a crash course.

Magic the Gathering: Arena seemed like a good fit. And it was! The game has a friendly, engaging tutorial that starts with the basics of playing lands, summoning monsters, and casting spells in semi-scripted duels against bots whose personalities reflect the theme of their decks. Magic is a famously complicated game, but MTGA is dense with helpful hints, highlighting all the cards in a hand that can currently be played, defining keywords like “trample” or “deathtouch” when clicked on, or warning me when I tried to play a card that I might be misunderstanding.

After a couple afternoons with Arena, I felt like I understood the rules well enough to go to the in-person Casual Commander without feeling like a burden to the other people at the table. I’ve gone back week after week, getting to know the other players by their decks and how they played, just like in the tutorial, riding the high of a new special interest and membership in a thriving subculture (word up to the Magic group DM).

I kept playing Arena, primarily because it was the easiest way to play more Magic between the weekly Commander nights. I climbed the ranks in PVP, feeling like a cards genius every time I beat somebody. But all too soon, I ran into decks that I simply didn’t have the right cards to beat, and playing with the starter decks was getting me eaten alive. I didn’t want to pay actual money for digital cardboard cards, so I leaned on the weekly and daily challenges that are Arena’s main source of “free” cards. These challenges gradually became an obligation. Whenever I didn’t complete them, well, shit. That was like throwing cards away! And I needed cards. I needed cards so I could beat people in PVP, so I could get more cards, so I could beat people in PVP, so I could…etc. I wasn’t even enjoying playing anymore. I just had to win, and when I lost, I felt like I was getting robbed. Totally healthy mindset, right? Very healthy.

In a moment of clarity, I uninstalled the game. I’ve got an addictive personality (more on this below), and while Arena is significantly less predatory than some free-to-play games I’ve been suckered by, it still has lots of little fishhooks in its design that tore at my fingertips whenever I’d try to put it down. The point where I’m playing a game less because I’m having a good time and more because I’m anxious about the opportunity cost of not playing the game is the point where I need to walk away from it.

Unpacking’s silent story

I don’t have much of an interior design aesthetic when it comes to video games. Given the opportunity to build/decorate a home base, I lean hard towards the utilitarian. I’m happiest with drab lockers to sort my crafting materials, named weapons, and all the other shit I’m afraid to sell because I might need it later. This is also how I live my life. Beyond putting up art because blank walls invite spiraling depression, I’m content for my things to just end up wherever, so long as I can find them later.

Unpacking asked me to inhabit the mindset of a person who actually cares where their stuff gets put, telling the story of someone’s life through glimpses of the days they moved somewhere new. The core loop is pretty simple. Given a room (or several) and some taped-up cardboard boxes, unpack the boxes, one item at a time, and find a place for each item. The only limitations are common-sense: clothes go in closets, shoes don’t go on the bed, towels go in the bathroom, etc. There aren’t any puzzles beyond the true-to-life conundrum of trying to fit more stuff into a spot than there’s room for. That’s good, because contrived puzzles would have undercut the verisimilitude that gives Unpacking’s storyits charm–and its teeth.

It’s a story told through inference and the accumulation of small details. In the “1997” level, I could feel the young protagonist’s excitement at finally having their own room well before the labeled photograph at the end of the level spelled it out explicitly. In “2007,” the shared interests between the protagonist and their new roommates can be divined through their matching tabletop game figurines and DVD box sets. When the protagonist moves in with someone who has a skyline view, but no room for the protagonist’s art supplies, well, that tells a story too. I don’t want to give too much away, but it’s a charming, cathartic experience, something I needed at the end of 2021.

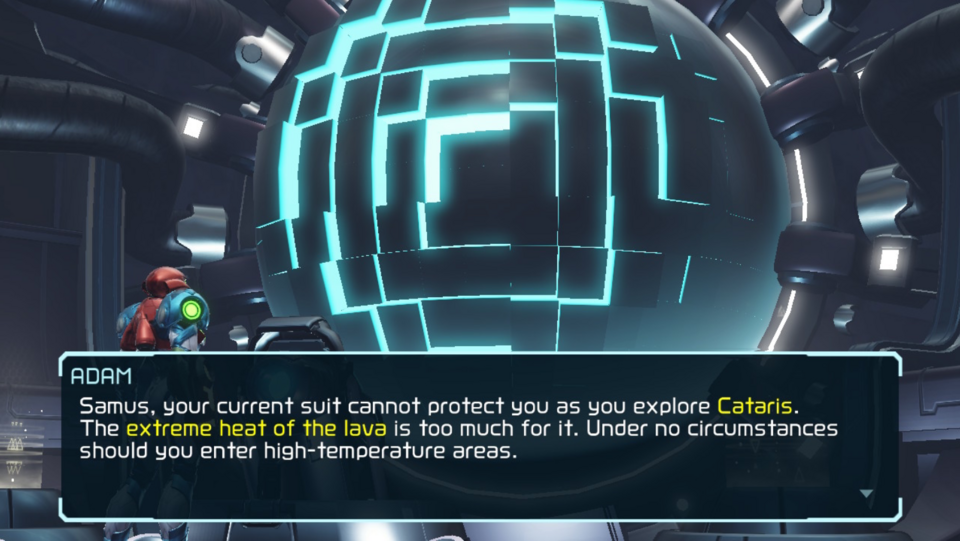

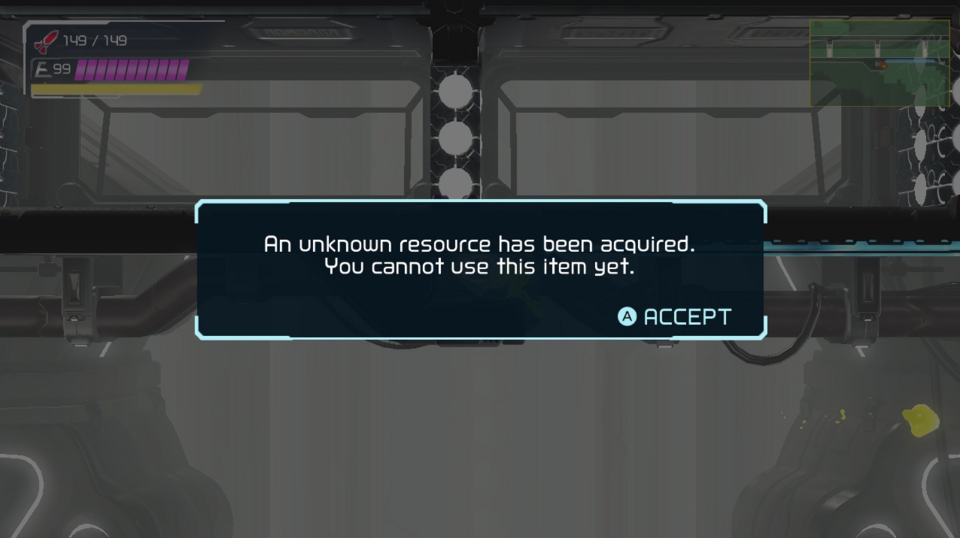

Metroid Dread’s linear exploration

Imagine a beautiful mansion where every door is closed. Imagine walking inside, trying to open a door, and discovering it locked. So you try another–locked! You try and try, jiggling every handle until you find a door that’s unlocked, and you open it. Behind it, you find a key! But what’s this? Why, this key’s the same color as one of the locked doors you already passed! Better backtrack to see what’s behind that door. Oh, it’s a key of a different color! Repeat until you unlock the door that rolls the credits.

The locked-door mansion is one of the irreducible progression models of game design (see also: “participate in a series of fights” and “gather resources in order to become more efficient at gathering resources”). The keys can be literal keys, but they can just as easily be something else: the fire arrow “key” opens the “locked door” of a progress-blocking spiderweb. The double-jump ability key unlocks the gap that can’t be crossed with a single jump. Bombs unlock cracked walls, fire armor unlocks fire. Killing a boss in one place unlocks a door somewhere else. Sometimes, instead of core-path progress, a door guards a health boost, ammunition, or a time-saving shortcut facilitating quicker passage through the mansion. It’s all keys and doors.

Metroid: Dread dangles its keys in a specific, intended order, one after another, funneling the player towards core-path progression with one-way doors and a helpful robot assistant to tell the player exactly what’s blocking their progress and where to go to clear it. I was a little disappointed with this aspect, honestly. When I backtracked to an earlier area to use a new weapon to unlock a door I’d noticed earlier, I received an “upgrade” for a weapon I didn’t have yet, which felt like yet another nudge back onto the path and away from exploration. Movement through the mansion of Metroid: Dread feels less like exploration and more like a guided tour, complete with frequent reminders to stay with the group.

That’s not to say the game isn’t great! I didn’t just put it on this list to complain that it’s a linear experience. It’s gorgeous, and the sound design is haunting, especially for the extremely tense E.M.M.I. encounters. The boss fights are a hoot. But it’s just a bit sad that the descendant of Metroid, a game so nonlinear that it inspired an entire subgenre built around aimless exploration, seems so afraid to let players get lost.

Powerwash Simulator’s meditative hum

I’m autistic, which in my case means I enjoy chores and repetitive tasks that non-autistic people typically find boring. I’m often recommended games from the simulator/simulation genre: Farming Simulator, Euro Truck Simulator, etc. For whatever reason, none of them particularly appealed to me (except for Train Simulator, which I’ve never touched for the same reason I’ve never touched heroin. Like I said, autistic.) But this year, I started hearing about a game that seemed like it might offer repetitive satisfaction without awakening a life-destroying trains obsession: Powerwash Simulator.

I grew up in the country, in a house built in the middle of a huge, dry riverbed. When it rained, the sand and clay would splatter, creeping up the outside walls, there to be baked by the south Georgia sun into long, forking fingers that threatened to grab the house and drag it under. One of my many country-boy chores was to haul out the pressure washer and break their grip. A pressure washer, as a brief aside, is basically a powerwasher but not heated. I loved it. The dull hum of the machine drowning out all distraction, the nigh-supernatural power of pointing at dirt forty feet away and watching it disappear, the satisfaction of seeing pristine emerge from filthy with a relative minimum of effort…it all coalesced into an immensely satisfying and meditative experience. As it does in Powerwash Simulator. The greatest compliment I can pay Powerwash Simulator is that it feels like powerwashing.

Conventional wisdom says games need power progression, so of course cleaning the vans, houses, and skate parks is not just its own meditative reward. I begrudgingly earn money that I use to buy soaps and upgrades to make the powerwashing go quicker. It’s an old trick, this dopamine rush: offer a repetitive task, then offer some upgrade that makes it go faster. There’s also an artificial scarcity to how many soaps can be purchased, encouraging that they be saved for when they’ll have the most impact. With every gamified element added, I feel myself getting further from the true soul of powerwashing.

But as the dirt falls away, so too do my worries, and I am lost once more to the hum.

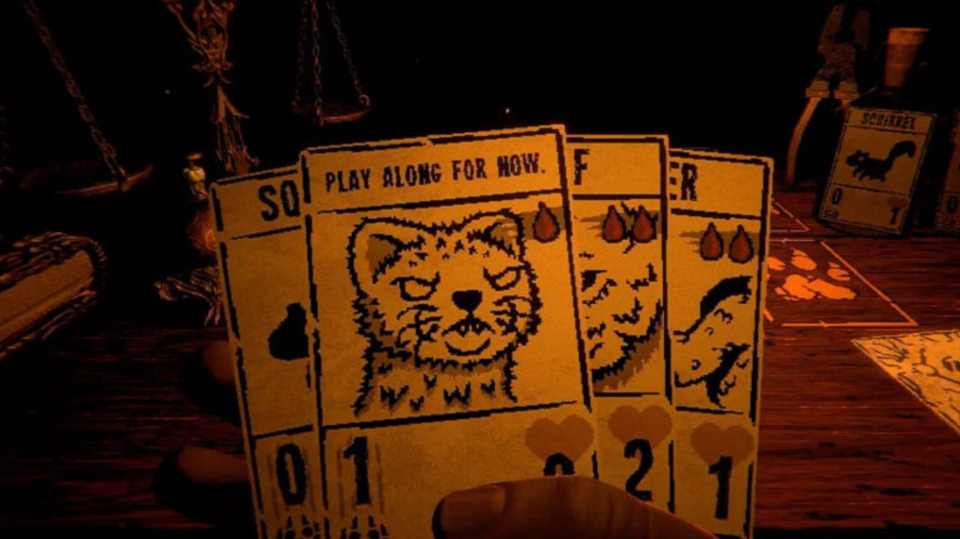

Inscryption’s Infinite Abstraction

Daniel Mullins’ games exist at the intersection of Mark Z. Danielewsky’s House of Leaves and a haunted Majora’s Mask cartridge creepypasta. Mullins seems to enjoy stacking his games with layers of narrative abstraction, here defined as a step of removal inserted between the media and the audience. In Mullins’ games, the player often plays as a person playing a game within the larger game being played by the player themselves, a conceit Mullins seems to have honed in his game jams (and previous release Pony Island).

Inscryption, his latest performance, begins at one layer of abstraction–the “new game” button is grayed out, with “continue” as the only selectable option. We are not playing our own game. We’re continuing someone else’s. Doing so opens to a first-person perspective shot of a hand holding several cards. A shadowy figure across the table unspools a style-heavy tutorial for a tabletop card game. So we’re already playing a game within the game–and then one of the cards starts talking.

The game pulls back again, the card game revealed to be connected to a separate gameboard/map. Branching paths on the map leading to story encounters/games played against a cast of characters (all played by the same shadowy figure wearing a host of wooden masks, another layer of abstraction).

One encounter/game asks the player to make a prediction based on three cards drawn from their deck; another is a game of chicken that lets the player strengthen a card at the risk of having it eaten. These games muddy the waters further: is the card game supplemented by the choices made on the map, or does the game being played on the map merely feature card games? Is the shadowy figure across the table our opponent in the card game, or a gamemaster simply playing that role? All of these layers of abstraction are already dueling for supremacy before the player is able to stand up from the table and move around the cabin, complicating things further. And that’s to say nothing of what happens within Inscryption when you lose–or if you win.

Inscryption’s metagame/narrative abstraction layers extend beyond the boundaries of game itself, raising the question of whether Inscryption itself is just a piece of the larger Inscryption ARG that played out on Mullins’ discord server, featuring clues hidden in Mullins’ old games and in custom cards he made for an entirely different card game. At every expected endpoint in this branching, there’s another another layer to peel back, another recursive plunge inwards. It’s a truly impressive effort that both encourages interpretation and resists simple answers, a narrative puzzle with shifting pieces borrowed from other puzzles. The more you zoom in, the more the game pulls back, the metanarrative equivalent of a vertigo shot.

Oh, and yeah. The game itself is really fun to play!

Resident Evil: Village’s power progression

So, spoilers for the first half of Resident Evil: Village. No way to avoid them, sorry. But man, I love the way this game handles power progression! You start off so weak, just trying to escape from scripted combat encounters. You’re hounded through a snowy village by infinitely spawning enemies, only to be inevitably bound and captured, forced to listen passively while the Four Lords argue over who gets to kill you. You crawl and scrape through Heisenberg Jigsaw’s mean bean machine, then sneak around the lavish Castle Dimitrescu, barely evading the seemingly-immortal vampire ladies keen to prey on you.

And then you’re caught again, and you just barely slip away, again, by ripping apart your own hand. But then, oh baby! You ever-so-gradually get more resilient and better-equipped, killing your captors one by one, the first almost by accident, the subsequent ones with intention. The hunted becomes the hunter! You get to know the Duke, breathing easy in his impregnable pop-up store as you spend the vampires’ treasure to upgrade your weapons. By the time you fight Lady Dimitrescu, the game’s first real boss, the power progression has inclined so gradually and steadily that your victory over a vampiric centaur-dragon seems only natural. You’ve gotten pretty strong now. You explore the village, much better-equipped than you were earlier, capable of killing anything you encounter. The helpful Duke points you towards your next goal: the Beneviento manor. Just a house! Not even a castle! How hard could it be?

Right at this moment, when nothing seems like a real threat anymore, the game pulls the rug out from under you, taking all of your weapons and forcing you to creep around again. You’re taunted with jumpscares and creepy notes from beyond the grave and forced into an extended lights-out escape-room segment where guns would be useless even if you had them. Suffice it to say you’re back on the bottom of the food chain.

By functionally resetting the power progression halfway through the game, Resident Evil: Village avoids the survival horror power creep that’s so poisonous to maintaining an atmosphere of dread. Following the Beneviento manor segment, the slow, steady incline established in Castle Dimitrescu resumes, culminating beautifully at the end of the fourth act. You do, in fact, get strong again. But Resident Evil: Village keeps the tension high by peppering in the odd high-health miniboss or unbeatable fish monster, reminding you regularly that it’s their village. You’re just visiting.

Psychonauts 2’s empathy

I was raised on Tim Schafer games and Jesus, but Day of the Tentacle and Grim Fandango made a deeper mark on my soul than anything in the Bible (Except the plagues. I couldn’t get enough of the plagues. Be careful what you wish for!). When Psychonauts came out in 2005, I was one of the several dozen people who bought it. I absolutely loved it, but, as we all know, the game didn’t do very well initially. I abandoned my faith in the god of Abraham that same year. I’m not saying they’re directly related, but, well. You can connect the dots. The pale march of time vindicated Psychonauts, however, allowing for a full sequel, all these many years later (At least one of my teenage belief systems paid off!).

I went into Psychonauts 2 with loud enthusiasm and quiet doubts. As excited as I was to pick up where things had left off…things had left off in 2005. The world’s moved on substantially since then, and the best of us have moved with it. In this particular case, we’ve evolved in how we depict mental illness. It’s easy to forget just how much of a punching bag the neurodivergent were in the comedy of the 1990s and 2000s. This is somewhat true, unfortunately, in Psychonauts. The back half takes place in an abandoned mental institution and the minds of its mentally ill former patients. While these characters are sympathetic, and ultimately healed by Raz, the basic nature of their mental illness is still played for laughs–look, this crazy guy’s in a straightjacket, so he has to play the board game with his teeth! Hilarious!

Just to be clear, this isn’t some decade-and-half-late, bad-faith callout post for Psychonauts. It’s ultimately a game with a lot of empathy for those suffering mental illness, especially considering the climate it was released in. That said, I was still a little nervous about it going into Psychonauts 2.

I needn’t have worried. Psychonauts 2 is an extremely kind, empathetic game, with an even more nuanced conception of the relationship between trauma and neurodivergence than its predecessor. In “Hollis' Classroom,” an early Psychonauts 2 level, Raz, the main character, changes some things around in his teacher Forsythe Hollis’ mind in order to get her to let him go on a mission, and the results are disastrous. After the damage is undone–which takes some time, as it takes a lot more work to heal a mind than it does to harm it–Hollis and Raz have a conversation about how violating his actions were, and what a betrayal of trust they represented. The wild thing is, entering people’s minds without their permission and changing things around to get past real-world obstacles was the entire premise of the back half of Psychonauts! This shift is all over Psychonauts 2–just as another example, Raz always gets permission from people before he first enters their mind through his psycho-portal, whereas in Psychonauts he mostly just sneaks up and dives right in.

This resonated with me most deeply in “Bob’s Bottles,” the level set in the mind of Bob Zanotto. Bob is an alcoholic mourning the loss of his husband, for which he blames himself. He’s withdrawn from the world completely, locking himself in a greenhouse and drinking himself into isolated, self-loathing oblivion.

I’m also an alcoholic, though fortunately I’m one in recovery. Alcoholism is a disease. Like most diseases, it’s not something you do to yourself. It’s something that you catch, something that germinates inside you, waiting for the right conditions to sprout. It usually stems from what’s called a “root”--some past trauma that causes us to turn to alcohol as a comfort, or an escape, or a means of self-medicating something else. Bob’s root is his aunt, who, like Bob in the present, dealt with the pain of losing her husband by isolating herself in a greenhouse and drinking to numb the grief. When she died herself, Bob entered her greenhouse, and his addiction and psychic powers blossomed.

Alcohol addiction is complicated. It can make you cocky, make you believe you’re in control of something that’s in control of you, like Bob’s severed head believing he’s in control of the bird that’s carrying him by the hair. “Caught?” Bulb Bob asks, rejecting Raz’s offer of help. “I got this feathered ferry service right where I want him.” At the same time, it can make you believe you don’t deserve love. It can poison your ability to accept help from people who care about you, even when you do realize you need it. Bob’s mental projections of his friends and family members all say awful things about him. But they’re mirroring his own self-hatred, not reality. As Raz points out, Bob’s mental image of his niece Lili has a totally different voice than the real Lili because Bob’s never met her. He doesn’t think he deserves to.

But alcoholism can be comfortable in the short term. It can seem easier than the alternative. The moth that represents Bob’s drinking problem spins him into a safe little cocoon, tucked away from the world, warm and numb. That can be a hard cocoon to break out of. Ultimately, it takes Bob’s mental projection of his husband saying something Bob knows he never would to shake Bob out of his detached oblivion. We call this a “moment of clarity.” It’s not just the recognition that you have a problem, but the sudden awareness that you’re the only one capable of fixing it.

I’m almost six years dry as I write this, but, like Bob, I’m still an alcoholic, because it’s not something that dies when it’s starved. It just stays hungry. It’s always there, watching, waiting for weakness. The past couple years have not been especially easy, but I take them one day at a time. Or as Bob says, once he’s back on the road to recovery, “Inch by inch, row by row..."