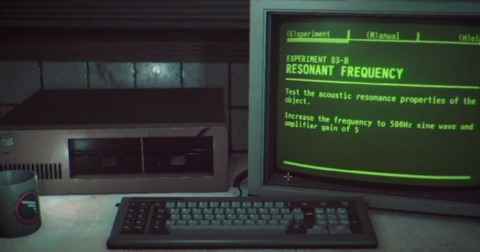

It’s a strange thing, as someone coming from the interactive fiction community, playing Devolver Digital’s Stories Untold. It’s a horror game that’s hard to describe; the first episode (out of four contained in the game) was released ahead of time and made it seem like Stories Untold was a straight piece of interactive fiction, an old-fashioned text adventure presented as a game-within-a-game. You type commands to interact with a text-based game presented in a vintage computer, in a lovingly detailed (but limited) view of what looks like a den in the early to mid eighties.

The full game, however, splits its time between that kind of interaction, point-and-click segments where you’re interacting with other types of “vintage” machinery, and even first-person walking-around sections. It’s also the kind of psychological horror game where details of the plot can’t really be talked about without spoiling them.

But what really interests me here isn’t the plot, as such, but rather the use of the text parser interface. It’s a type of game with a long history, and one that I know decently well. But playing the text adventure sections of Stories Untold made it clear to me that the call was very much not coming from inside the house; Stories Untold is more interested in the idea of what a text adventure is, than in the reality of the parser interactive fiction that has existed for the last 40 years.

The game lacks almost all of the affordances parser games have developed to better understand player commands, and it’s not really structured as a traditional parser game. Those games have a layer of simulation, a world model, that players interact with. Text adventures are historically about the manipulation of “middle-sized dry goods”, the sort of items (a crowbar, a can of soup, a screwdriver, a box of matches) that adventure game protagonists compulsively pick up as they are found. Stories Untold’s text adventure segments feel more like a choose-your-own-adventure story; only instead of being given explicitly listed options of what you can do next, you have to type in commands that match those pre-determined choices. Failing to type a valid command is met with a plaintive “I’m sorry, I don’t understand,” and players are so expected to hit that wall at one point or another, that the phrase itself takes on plot significance later on.

This is, of course, a stylistic choice; Stories Untold is all about the friction of interacting with old, finicky machinery. It’s about deliberately uncomfortable design; its machines are meant to evoke dread with their dumbfounding incomprehension of what you want to do.

But it does mean that the game deliberately pushes away its own history, distancing itself from its parser IF predecessors. Which is something of a shame, because Stories Untold can’t fully escape the shadow of what came before it. To understand how, it’s helpful to look at those predecessors; to put Stories Untold in the exact IF context that it seems to resist.

The Lurking Horror (Dave Lebling, 1987) is Infocom’s first foray into horror. Infocom, a US-based developer of interactive fiction, had its heyday roughly around the same era that Stories Untold is referencing. This was a time when parser-based, text-driven adventure games were the main vector for narrative gaming, and Infocom made the most sophisticated examples of the form. As interested in literary genres as anything, Infocom brought many themes and ideas that were new to games: Romance, mystery stories, political allegory, and, of course, horror.

Lurking Horror is an odd, transitional piece. It’s still very committed to Infocom-isms even as it explores a genre (Lovecraftian horror) that was new to them. Set in a stand-in for the MIT campus, it already draws a line between computers and horror; instead of a book of forbidden knowledge, the protagonist inadvertently connects to a server containing such a document. Many of the standards of the survival horror genre show up here: A weak and confused protagonist; a conveniently isolated setting (in this case, the campus is snowed in by a blizzard); collecting pieces of text as a way of advancing the plot. It doesn’t have the benefit of jump scares (though it does introduce audio as a way of building atmosphere) or horrifying visuals; it’s much more about slowly mounting dread than about shock.

And it’s odd seeing Stories Untold reference the tropes of the survival horror genre; some of those ideas do go back to The Lurking Horror, but they’ve clearly been filtered by generations of games in between; gone is the clever spatiality of Lurking Horror’s puzzles. Instead, at one point, Stories Untold asks us to type a code into a four-digit keypad lock; a moment that feels almost like a dig at the triteness of modern horror game interaction.

Anchorhead (Michael Gentry, 1998) is, for the “classical” era of hobbyist parser IF, the ur-horror text. It’s larger and more complex than Lurking Horror, an enormously ambitious piece. It’s also dripping with the sort of overwrought Gothic atmosphere we associate with HP Lovecraft. Here, the mechanics of world-simulation, which Stories Untold eschews, are used to deliver atmosphere. Any outdoor location might batter you with rain; crossing from inside to outside entails the player character opening her umbrella. It’s first and foremost an atmosphere and mood piece, even though it still wraps itself in the traditional puzzles-and-plot structure of a parser adventure.

And atmosphere is really where Stories Untold puts most of its attention. Depending on the chapter, rain or snow might pour outside; thunder might crash at opportune moments, or the lights might flicker. Sometimes there’s clinical fluorescent lighting overhead; sometimes the environment is lit only by the machines you’re interacting with. But in Anchorhead, there’s this tighter integration between atmosphere and interaction; the game works harder to “sell” its environment through the actions the player is forced to take. You’re occasionally compelled to manually open the umbrella, so as to stop the player character from getting soaked. You might squeeze into dusty crawlspaces or descend muddy inclines. In Stories Untold, there are first-person walking segments that are a little too detached to quite place you in that space as effectively as the text-based interaction in Anchorhead does.

Slouching Towards Bedlam (Star Forster and Daniel Ravipinto) is as much a metatextual, Borgesian piece as it is a horror story. It uses the format itself, the conventions of video games and adventure games in particular, as a narrative device and a source of dread. Saving, loading, and restarting the game are treated as plot mechanics; and, in places, needed to fully explore the story. Slouching wants you to do things in the game before you explore or interact with the world enough to understand why you would do them; it wants you to restart and use knowledge you got from a previous play session. And in this, it achieves the sensation of really being a horror protagonist, of having terrible knowledge and bringing yourself to act on it.

Stories Untold is too much of a psychological piece to really achieve this. It keeps the player in the dark, more or less constantly, operating exclusively on nightmare logic. But, using its limited palette of options, it still constantly presents the player with the forced choice of doing something horrific; of being the object of horror in the nightmare, rather than merely encountering an object of horror. Like Bedlam, it uses its own structure to gradually build the player’s knowledge of horrifying events, but it never really drives into the payoff of having the player make a choice based on that knowledge.

Lime Ergot (Caleb Wilson, 2014) is entirely about perception and genre convention; in a way, it steps outside of psychological horror and in the direction of social horror. Lime Ergot is a bird’s eye view of horror, built around bending the idea of space and proximity in a way only a text game could, in order to produce an effect of complete dislocation. In Lime Ergot, you essentially move by looking at things, your “vision” telescoping around time and space in a sickening motion as you feel around for the objects you need to complete the story.

Stories Untold, too, relies on dislocation. More than once, it uses its game-within-a-game conceit to put the player character in two places at once, to great, horrific effect. Again, here, text is key to perpetrating the effect; there are two layers of reality that seem wholly separate, until they’re crashing into each other.

But all this isn’t to say that Stories Untold compares poorly to what came before it. It’s very much its own thing, and worth playing. But it’s such a different experience to play it when you have all this context; to know the references it’s not making, almost pointedly. Games have been around for long enough, now, that the earliest days of the medium can be referenced in a vague way, an indirect way, that doesn’t quite represent what they were like. The reality and complexity of early parser games has been abstracted, in the way that all mediums ultimately start to digest and simplify their own history. People working in the medium make choices about what, in those early formats, is characteristic and worth preserving; we’ve all seen the way that “pixel art” has conventionalized the technical limitations of early platforms in ways that are not always true to the original hardware.

Stories Untold represents a similar step for the text adventure. It cares about the screeching sound of the ZX Spectrum extracting data from cassette tapes. It cares about the eerie amber glow of those screens, and about the act of typing into a text box. But it doesn’t necessarily care about the world modeling that came with that style of game, or about the specific tropes of interaction and perspective that those games embodied.

And it’s different, too, in that parser IF is still a living practice today; a few months from now, the Interactive Fiction Competition will happen once again, and there will be parser games in it. Some will be long and ambitious pieces like Anchorhead; some will be short and direct like Lime Ergot. And the existence of that continued practice makes Stories Untold feel so much like an artifact deliberately trying to escape both the time that made it, and the time it’s trying to reference. It’s a piece about nostalgia for a thing that isn’t quite dead yet.