(If you have not played The Walking Dead up through episode four, do not read this. Spoilers abound!)

- The Walking Dead's Faces of Death, Part 1

- The Walking Dead's Faces of Death, Part 2

- The Walking Dead’s Faces of Death, Part 3

It’s almost over. After Jurassic Park, few could have predicted Telltale Games would have come up swinging as hard as it did with The Walking Dead, but few games have proved as emotionally affecting as the harsh journey of survival for Lee and Clementine in a world gone totally mad.

If you’ve been following along the past few months, I’ve been chatting with various members of The Walking Dead team at Telltale as each episode closes, and the new one approaches. There is (sadly) only one episode left, and episode three was one hell of a tough act to follow. The final moments with Kenny’s son, Duck, will be remembered by players long after this season has come to a close.

The huge reaction to episode three prompted the designers of episode four, Around Every Corner, to head in a different direction.

“We’ve stuck to a lot of the things that we were doing in one, two, and three just because of production reasons," said episode director Nick Herman. “And with four, we wanted to give some new experiences to the player. You’re alone with Lee for the first time, there’s some sneaking around, and there’s this big mystery about the episode--it’s really compelling. If you look at the season as a whole, you look at the structure of everything, and one, three, and five have the critical things that have to happen, and two and four allowed the player to do something different.”

Episode four was penned by a familiar face to Giant Bomb fans: Gary Whitta. Though Whitta has been a story consultant for the entire season, he actually wrote the script this time.

“Each episode has its own energy,” said Whitta. “Episode one feels like a pilot, which is almost what it is. Episode two was a cool, creepy, self-contained horror movie. Three is the all-out emotional drama. Four is the action thriller, where we allowed ourselves to cut loose and do a few things we think the players [needed]. We put them through such an emotional meat grinder in episode three.”

In previous entries, we’ve specifically focused on the influence players have with death in the series. There’s not as much of that in episode four, so I decided to walk through each of the main stats that Telltale was tracking (and continues to at www.walkingdeadstats.com) and make that the focus of our conversation. That, of course, still includes plenty of death talk, including how Whitta and Herman convinced some of you to finally cut ties with Ben.

We’ll return to talk about the final episode of The Walking Dead, No Time Left, in the next few weeks. Telltale has not announced a formal release date for the last episode, but it’s coming soon. From what I've heard it, it's...damn.

GB: It seemed like this decision was framed to echo a choice you recently had at the end of episode three. You have the dynamic between Lee and Kenny and someone of similar build and age to Duck. You’re given the chance--again--to be the person who takes care of this situation or allow Kenny to do it. I chose to take care of it myself again, but was honestly surprised more people didn’t view this as a cathartic moment for Kenny, and actually have him do it.

Herman: I didn’t have any expectations for that. When we were building that moment, we knew it was going to be close to some of the moments in three. We put more time into the moment after that--Kenny recovering from whatever happened in the attic, and burying the kid with his dog. Getting a chance to put the kid to rest. I don’t know. I wasn’t really surprised by what people did in the attic.

Whitta: I think it’s one of the more interesting choices in the game, in that we talked about how we try to present these morally ambiguous choices [and] this choice is ambiguous. Not necessarily from a moral standpoint, but it really depends on how the player interprets what the choice means. It’s very easy to look at it in terms as you said it--an emotional echo of the dark choice in three. You feel like you’re protecting Kenny by taking care of this and not putting him through that horror again. But at least 25% of people assumed that it meant the other interpretation, which is to say that you’re actually helping Kenny by helping him get back on the horse, and by taking this action, you’re helping him. In a way, it is cathartic and it is therapeutic and it helps him deal with the horror of what happened to Duck. People that played that choice through and had Kenny do it, you’ll notice that it actually plays through in a very sympathetic way. It’s not about Lee giving Kenny the gun and saying “I can’t do this, you’ve got to do it, I don’t care about your feelings.” It’s “you need to do this for yourself, this is something that can help you.” That’s certainly what we intended, and if I don’t know if everybody saw it that way, but people that did make that choice did understand that both choices could be perceived as protective of Kenny in their own way.

Herman: And you can walk out of the room. That’s an option that people don’t know they have.

GB: Wait, really?

Herman: Yeah!

Whitta: People don’t know you can do that, and that’s a choice that we worked with to make sure all the hot spots are visible, and you can just walk out of the attic trap door, which is probably the only “bad” choice there.

Herman: Even then, though, Lee looks back up to Kenny and says “let’s go, man, let’s get out of here. We don’t have to do this.” Kenny wants to stay and wants to handle it.

Whitta: Basically, if you leave, Christa goes up there and takes care of it and brings the body down and says “you didn’t want to face this, you can at least bury the kid.” It’s interesting in the sense that it’s the scene in the game that got revamped the most. This was actually originally a tension-type scene--the kid was crawling towards you and you had the moment where you had to make a choice before the boy could maybe grab you and bite you.

Herman: It was a sad scene. You were trying to pick him up, and he was falling apart in your hands. It was really gross.

Whitta: In the end, we felt it worked better as an emotional echo. It was less about tension, and more about tragedy. We really, really overhauled that scene, we took the timer off, we really wanted players to sit in that moment and think about what the choice meant to either take care of it yourself or give it to Kenny to do. When we listen to people play through and listen to their commentaries, it definitely is one of the harder [choices], all the way up to having to bury the kid. It’s one of the darker moments in the episode.

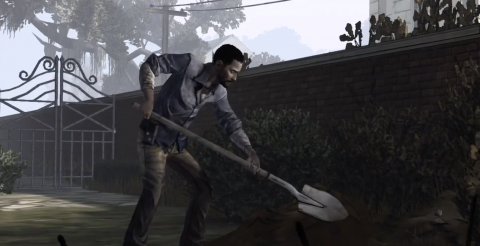

GB: It seems like it would have been very easy to make the scene where you have to bury the kid and have button prompts to fill up the dirt--that could have easily been a cut-scene.

Herman: It got toned down a little bit after playtesting. It was much more involved, many more clicks. [laughs]

Whitta: It used to be one click to do the dirt, and then another to dump it, and it was too laborious. We had to scale it back.

Herman: We always wanted the player to feel like they were involved with the act of burying this kid. In hindsight, I wish we could turn it down a bit--it seems like it might go on for a bit too long. It’s just so dark, and especially when you’re putting the kid in his grave with his dog, it’s just a boy and his dog. It’s so sad. It’s a good transition into the next scene with Kenny, and it just had to go there.

Whitta: Again, I think if we had it over again, we may have scaled it back a little bit even more. Having the player do it makes it slightly more grim, and, in a way, worked. Right at the moment the player is saying “okay, I’m done shoveling dirt,” we hit them with what I think is the best jump scare in the game. In terms of pacing that out, it actually worked out pretty well.

GB: The game is certainly, up to that point, creepy and unnerving, but that was probably the first time the game managed to get me with a jump scare. As a horror aficionado, jump scares take a lot to get me, but to your credit, you did.

Whitta: Yeah. It’s interesting to talk to someone like yourself, who I know is a big fan of horror. I’m very strongly of the opinion that jump scares are the cheapest and easiest and laziest way to get a reaction out of an audience. We use them a few times, but we ration them. We have a few good ones, but especially when they’re bogus ones--a cat jumps landing on a ledge or something--and there’s a big sound to go with it, it’s just a forced alarm. What’s interesting is the most effective one in the game is the one outside the fence there. It’s just a quiet moment, and it’s very clever that Nick directed it. You go to that shot the first time, he bends down, and there’s nothing there. The second time, there is something there. I think it’s directed very, very well to get the right reaction.

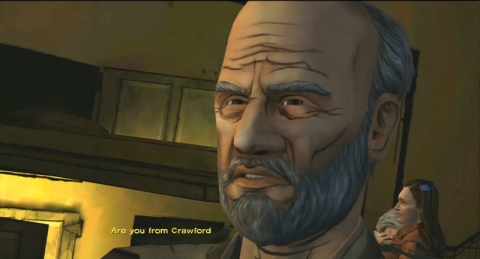

GB: When you have the chance to rationalize with Vernon or threaten him, this wasn’t a decision where someone can die as a consequence. This is a moment where you don’t have Clementine at your side. Based on my own experience of how I’ve played, when people don’t have Clementine at their side, they indulge in their darker side a little bit. I wasn’t surprised when the stat choice here split more-or-less 50/50.

Whitta: It’s interesting, actually. Once you get separated and go down into the sewers, that’s actually the first time in the entire game that you’re completely on your own and separated from the rest of the group since you met Clementine in the beginning of episode one. We deliberately separated them, obviously. It’s interesting what you say about people feeling better about maybe acting a bit more renegade when they feel like Clems not around. A lot of players are still afraid that Clem might still be there. [laughs] When you killed that St. John brother in episode two and Clem was there...

Herman: That scarred people.

Whitta: It instilled a fear in them that we might pull that trick on them again! It would give them license to do something bad, and people are constantly looking over their shoulder to see if Clem might be watching them. They felt fairly safe in this instance, and they were definitively separated from her. If you do choose to threaten Vernon, it does lead to some of the more fun Lee stuff in the game. He gets to act like a total bad ass, and probably the most bad tough guy character in the game up until that point. You can definitely have some fun with it.

I think most players, obviously, are going to, again, try and reason and try to be the good guy. What I think is interesting, as well, is not all the choices in the game are telegraphed. Sometimes when you have a long timer and a binary choice, it’s very obvious that you’re being faced with one of the five big choices in the game. With Vernon, whether or not you chose to threaten or lie to him, isn’t really telegraphed. You don’t necessarily know it’s one of the most important choices until the game is over. I think that’s something we might want to do more of in the future. We don’t always make it clear to you that this is a very consequential choice. You may not realize that until after the fact.

Herman: It just reinforces the fact that everything you do in this game, everything you say, we’re tracking. We can make decisions on them, and people should always be on edge about what they say, even if Clementine isn’t around. It’s important what the people around you think. They have an effect on your life, as you see at the end of episode four. It’s not just the big choices that add up in the game, it’s how you’ve treated these people this entire journey, and it comes back to you.

Whitta: It’s just an opportunity for the player to roleplay. “This is the kind of character I want to be. I’m not necessarily going to be thinking about consequence.” But just making their own internal moral choice about how they want to treat people.

GB: In that situation, there’s no rationale way to say Clementine would have been stalking you into those sewers. Even if it’s not the idea that Clementine is watching, it’s that ever since that moment, you see people err on the side of trying to be the good guy. Somehow, this is going to come back to haunt you in a way you can’t expect because that moment with Clementine set this expectation.

Whitta: Absolutely. One of the interesting things about doing an episodic game is seeing how people have reacted to previous episodes, as we’re continuing to make the latest ones. One of the big things that we learned was that in a world with these morally ambiguous choices, people really tend to urge towards taking the righteous path, the heroic protagonist. In a game like Mass Effect, you’re given these morally unambiguous renegade and paragon choices, and a lot of people choose renegade because it’s fun and delicious to be the anti-hero. But in a game like this, where it feels emotionally more grounded, more shades of gray, people don’t find playing the bad guy as much fun. The game feels more realistic to them, and they want to act the way they would in real-life, and everybody wants to feel like they would be the good guy.

GB: When you have the choice of whether or not to bring Clementine with you, or to leave her at the house, that split about 75/25. When I’ve talked to Sean Vanaman and Jake Rodkin in the past, it’s not that every decision needs to be 50/50, but the goal is to err towards presenting an argument that gives people two reasonable options, even if more people trend towards one. With this decision, do you feel it going 75/25 was because it was an unwinnable argument about why Clementine should be left in this house with this guy dying?

Whitta: What I’ve learned is that the raw number doesn’t always tell you the whole story. Again, I watched a lot of playthroughs--a lot. It was fascinating to me to see how people reacted, and when that timer comes up, and they’re given that choice to leave Clementine or bring her with, a lot of people pause the game at that moment because they agonize a lot over that choice. Even though three-quarters of people went one way, one-quarter went the other, if you look at the actual decision making process, it’s a much more difficult choice than the numbers suggest. And it’s been really interesting to go onto forums, and probably only second only to Ben, it’s been the most contentious choice in terms of the ongoing discussion. You talk to people that left Clem behind, and they have what they believe are very, very solid, very well thought out, reasoned arguments for why you left her behind. No matter what you chose, you can’t possibly believe that anyone else would have done the other thing. [laughs] It’s by far the most polarizing choice. Even on Ben, they can say “well, I understand why you would save him.” If you talked to people about Clementine, whatever they chose, they’re convinced that’s the only choice and the other choice is madness. I actually think that choice worked out really well.

Herman: I wish more people had left Clem because when you’re with Molly in the hallway, if you don’t bring Clem, you’re responsible for saving her life, and just I like that being a thing. And Molly can be left behind. You can shoot her, you can miss, and let her just get taken down.

Whitta: It’s the only choice in the game where I want to nudge people one way or the other. If you take Clem, you get is my personal favorite moment in the game, which is Clem saving Molly. It’s really, really tough, and we did put a lot of work into it, always trying to weight the scale. How can we make a convincing argument to the player for keeping her here? How can we make a convincing argument for leaving? We have Clem bring up the idea that Amid could turn, right? And maybe bite her. A lot of people are worried about the guy outside the door, the guy outside the fence--he might come back. Eventually, what I think weighted it to the majority for people bringing her was that people ultimately feel that even in a more dangerous situation, Clementine is always safest with Lee, with the player.

GB: Anytime Clementine comes up, given that she is this Kryptonite for the player, it really ups the stakes. There can be a diminishing impact of that, if every time she is put into danger, there is actually no consequence. As designers, you have only so many times you can play that card before the player starts to catch on. How do you balance against the impact you can get from involving her without getting players to think “oh, well, they’re not going to do anything”?

Whitta: In four, she’s not in danger that often. Earlier, she’s not in mortal danger that many times. As a larger idea of Clem, I think you’re right. We are constantly aware of how potent a character she has become. People are so emotionally attached to her, they care about her so much. I’ve genuinely never seen anything like it in video games. We are very aware of not wanting to overplay that and be aware of the fact that with Clementine, a little bit goes a long way as an emotional totem, as a way to make the player afraid for her. You’re right that it’s pretty easy to overdo it.

Herman: Just as people started to catch on that we might be using her as a card, we took her away, right? [laughs] Keeping it fresh! [laughs]

Whitta: That’s really the trump card that we play at the end of four. We take her out of your own ability to protect her entirely, and the episode ends with her in the wind, and you know you can’t protect her anymore, which is why people hated us so much at the end of the episode. Rightly so. One of the things that comes up often is when we’re dealing with a story problem and “how can we make this more interesting?” someone will eventually say “let’s put Clem in the room” or “let’s take Clem out of the room.” We’re very aware that can sometimes be a storytelling or emotional crux to tip the scales either way, and we want to save those moments for when they’re the most potent, when they’re the most appropriate. Otherwise, you can overuse her in a number of different ways, and you’re right, you could get into a world of diminishing returns.

Whitta: I think the one that we spent the most time agonizing over was Ben. The attic boy and Ben were the two that we spent the most time on. Ben was the one that we were most worried about. We’ve put a lot of work into this idea that there are no black-and-white moral decisions in this game, everything is gray, and as a result we get these 50/50 splits whenever possible. Dropping or saving Ben was the most morally unambiguous choice presented to players so far. We’re deep enough into the season now to know that most players want to be the good guy, and they’re not going to kill anyone unnecessarily, they’re trying to play the righteous, paragon-type path. When we playtested that episode, nobody dropped Ben. We were zero-for-nine on people dropping Ben, and we went “This is broken, we’ve got to find ways to convince people to drop Ben, basically.” [laughs] Otherwise, it won’t be interesting. [pause] Not to convince people to drop him, but to make it a more difficult choice.

Herman: Without making Ben a villain, though. That was something I was worried about.

Whitta: I think Ben is really interesting in that he’s not the typical antagonistic threat to the group. If you look at someone like Merle in the TV show, it’s very easy to understand why people don’t like him or don’t want him to be in the group--he’s a douchebag. He’s a threat to the group, he’s a danger. When you’ve got someone like Ben, who’s just a good natured kid that wants to help but he’s just kind of an [idiot], he’s constantly putting people in danger despite his good intentions. That’s a much more difficult question. What do you with a guy like that? Do you cut him loose for the good of the group, or do you say “We’re going to buck it up and be a group and absorb him and try to help, be a bit more charitable about it.”

After the playtest where nobody dropped him, we went back and looked at what we could do try and move the needle back towards the center. Having him abandon Clem, for example, in the street in the opening scene, that’s something we added back in. That ended up being a huge motivator for players. That was the straw that broke the camel’s back for Ben in many ways. We actually went back and re-recorded a lot of Ben’d dialogue to make him a lot more assertive, a lot less whiny. We totally redid all of the dialogue with him in the sequence in the bell tower to make it--again, try to make arguments for dropping him and saving him that felt really strong, and letting players decide. In the end, the 2/3rd to 1/3rd split we got was better than I hoped. Given, again, we expected most people to try and do the right thing. We got 33, 34% of the players to drop him, I think is pretty impressive.

GB: I chose to not be a monster and to not drop him.

Group: [laughs]

GB: For me, it was a consequence of an earlier choice to bring Clementine along with to gather the equipment. There’s a specific moment in the group conversation where you can give Clementine a vote, and she comes to Ben’s defense. Clementine has this ability to disable the player--it’s Kryptonite. Because she came to his defense, I’m pretty sure that’s what rang true when I was given this moment to let him go, and had that moment not occurred, I don’t know if I would have made that same decision.

Whitta: I don’t think it’s a coincidence at all that taking Clem to Crawford and saving Ben are both the majority choices. I think one very much leads into the other. What we’ve learned, especially in episode two when Clem saw you kill one of the St. John brothers, is that people are very worried about how their actions reflect on Clem. They want to protect Clem, not just physically, but emotionally, and she is the moral compass in the game. I watched a lot of those Let’s Play videos, and they’re incredibly instructive because you see how people act in these moments in real-time. You hear their thought process live as they’re playing the game. When that discussion came up to vote Ben out, people who brought Clem were all ready to vote against him, and then Clementine registered her vote, and you heard “oh, shit, now I can’t vote against him!” Because they’re so concerned with how Clementine views Lee and the moral choices she’s exposed to. If you brought Clem, you were most likely to save Ben, basically.

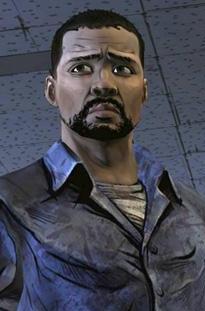

GB: When Lee is bitten by a zombie, I have to imagine this was a plot point established internally pretty early. The entire episode is framed around this big moment that changes everything that’s happened before it, and frames everything for what’s to occur in episode five. How did you approach how that scene played out, when to reveal it, and whether anything significantly changed?

Whitta: This one actually didn’t change that much.

Herman: We knew this from the beginning. Gary had always been saying “we want to keep saying ‘Clementine stay close to me, stay close to me.’” And, then, when she’s so far away from you, there’s this huge “oh my god, what do we do now?” [moment]. We knew this was going to be at the end of the episode, so we had the moment earlier in the episode where you’re looking for her and she’s missing, and it’s this little bit of a fake out but also a little bit of a foreshadowing of what’s to going to happen at the end. We were always playing towards it.

Whitta: In a way, it’s a double cliffhanger. Obviously, you have the one element in that Lee’s been bitten, and what does that mean? Again, it’s been very interesting to see players have fits over that, digging up old quotes from Robert Kirkman about whether a bite is always fatal. [laughs] People are really holding onto the idea that Lee might be the chosen one or immune or that they could cut the arm off and that would save him. Other people are saying “deal with, deal with it. He’s gonna die.” Some people have made their peace with it, other people are still in denial over [it]. Did we effectively kill Lee at the end of episode four? You’ll have to wait until episode five to find out, I guess.

People certainly had a very strong reaction to it. The other side being that Clem ends up in danger, and basically out of the game at this point. When we did the first start of that, when you come back from the sewers, and she’s gone and people are freaking out until they find her in the boathouse, that’s when I felt like that moment was going to work. Any time that Clem’s whereabouts are unknown, even for a brief time, players start to panic. The fact that we ended an episode that way, with her in danger and you have to wait until the whole next episode to see what’s going to happen, that, more than the bite, might be why people are freaking out so much. I think a lot of people are holding on to the notion that Lee is salvageable. I’m not saying he is or he isn’t, but it’s been very interesting to see people argue over what it really means.

GB: I think that tells you the moment was effective--people are trying to rationalize something that’s completely crazy. It tells you that people have come to really care about this character, and will do all they can, including digging up quotes about the fiction, to justify this personal narrative that they want to play out, even if all the evidence in front of them points in the complete opposite direction.

Whitta: It’s very satisfying, it feels like we’ve done our jobs, that players love Lee. I said to Sean Vanaman earlier in the week--and I’m not blowing my own trumpet here, this is all about what Sean and Jake and the rest of the guys did--I genuinely think with Lee and Clementine, they’ve created video game icons. They are now going to live on in the pantheon of great video game characters of all time. I’ve never seen an emotional reaction to video game characters like I’ve seen to Lee and Clementine. And that’s why people are freaking out so much, that we’ve jeopardized both of them so heineously at the end of episode four. We don’t know if either of them are going to survive. Watching people panic is very satisfying because it means we’ve done our job in making players fall in love with those characters.

In term of the choice, the only choice in the game that I wasn’t satisfied with was the bite. Going back, I would have done it slightly differently. Talking about the 50/50? Sean Vanaman doesn’t actually believe in the 50/50 mantra, and I don’t anymore, either. I kind of do believe in 50/50, but in a different way. If you can get in the middle 50, so 75/25 each way, as long as you’re in that middle 50%, I think you’re okay. This is the only choice in the episode that fell outside of that, it was 80/20.

Herman: What bums me out about it is that if you show the bite, Christa and Omid come no matter what. That blows away some of the “let’s reflect on how you treated people and they’ll make that decision based on that.” Which makes sense when we were designing it, it’s just now seeing what the stats are like...

Whitta: In this part of the episode, that scene at the end, there’s at least eight different outcomes to that scene, and there’s multiple ways to get to each of those eight outcomes. It was a nightmarish scene.

GB: I can’t imagine what the script looked like.

Whitta: It was awful. It was even worse in episode five because all those outcomes have to be dealt with in episode five, and the opening act of episode five is so radically different, based on who you brought with you. It’s going to be really, really interesting to see all those play out.

The one thing that I would have done...I think most people assumed that Kenny and Christa and Omid are basically good people that are on your side, and showing them the bite wouldn’t necessarily have a negative repercussion. Hiding it might because they know, in the world of the Walking Dead, it’s going to come back soon or later, and you may as well be honest about it now. If there was a character like Larry still in the group, who you can imagine might make an argument to cast you out for being bitten, people might have been more afraid to show it. And, again, playtesting doesn’t always tell you everything. In playtesting, it was 50/50. But you don’t know until you get it out into the world what the real stat’s going to be, and so I was slightly disappointed that more people didn’t hide it. If we were doing it over, we might have rearranged some elements to make a better argument for hiding the bite.

Herman: Another thing that might have played into that is that when you hide the bite, you get a chance to show it again. That shot us in the foot.

Whitta: The other mistake we made is that it’s the only choice in the game that you get two chances at. I don’t even remember now why we did it.

Herman: It was because it felt like a natural thing to do. If you said “no, I want to hide the bite,” and then someone came along and said “Lee, you’re my best friend, you tell me everything,” you would have the opportunity to say “look, dude, I hid this from you earlier, but here’s the bite.” That’s what happened.

Whitta: The one thing that would have pushed the stat back into my comfort zone--again, Telltale tracks everything, we know how many people revealed the bite on the first opportunity, how many people revealed it on the second--and it was a statistically significant number of people that revealed it on the second opportunity. I think two things were happening. People either had more time to think about their decision and second guessed themselves, or they saw the fact that we gave them a second choice and somehow felt the game was trying to push towards doing that, that it was the right choice. In retrospect, if I could put one band-aid on it right now, I would take away the second opportunity to reveal the bite.

GB: Part of the reason people feel so strongly about what occurs in that moment is that the series, has done a pretty brilliant job of, at times, giving players influence and agency over the actions occurring. But at the same time, constantly taking that away from the player. It’s a fairly linear game, but the choices make it feel like a much more non-linear. When Lee is bitten, there was no QTE, no dialogue choice. There was nothing the player could have done differently, and that’s an instance where the story is going in a specific direction, and the player has no real impact on whether that could or could not have occurred. People are upset because it’s happening to Lee, not that it’s cheap and the game is putting something in a cut-scene that I would normally would have had influence over.

Herman: We were pretty worried about how people were going to take that. We were worried about what you were just saying was going to be a problem. If people were saying “what the hell? I didn’t want to do that. I had no control over that!” So there’s actually two things you can click on. You can click on the walky talky, or you can click on the trash where the zombie is. We wanted to throw that in just because if people rewound, we didn’t want to force them to one spot, so we gave them another option to catch the zombie no matter what.

Whitta: A lot of the game is, as many works of art I guess, are smoke-and-mirrors. We’re creating an illusion of a choice there that isn’t really there, but ultimately players often come away feeling like something different could have happened, and that’s good enough for them. A story point as consequential as that was always going to be the critical path. I don’t think we ever could have the player choose to be bitten or not and have different directions based on that because it’s part of the ultimate story that we want to tell. Nobody complained too much about feeling that they couldn’t control the bite, they accepted that as part of the story. Players complained a lot about not being able to save Doug or Carley in episode three, but as Nick has talked about before, it’s interesting when you give a player agency, they often assume that means they should be masters of the universe, and they should have control over everything that happens. When they don’t, the game is cheating somehow.

But the reality is that in The Walking Dead and in real-life, you don’t have control. You’re not the master of the universe, you’re not the master of your destiny. Shit happens, and you don’t always have a say in it. When someone just pulls out a gun and blows someone’s brain out too quickly for you to react, that’s just something you have to deal with it. You’re often powerless. That’s an easy thing to do in linear storytelling, but when you give players a choice, you have to ration those moments so they don’t feel like they have agency taken away from them.