Time travel's often viewed as a cheap, desperate tactic for storytellers, an all encompassing deus ex machina that both solves and creates a million different problems.

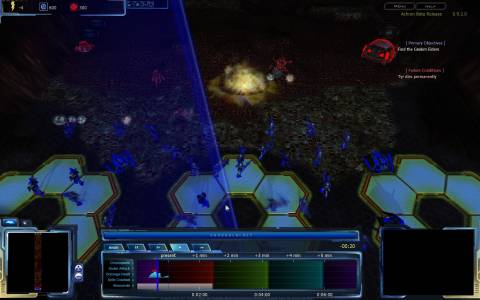

Hazardous Software founder Christopher Hazard came up with the idea for his time travelling real-time-strategy game, Achron, back in 1999, and spent the years after working out the kinks.

Turns out there were a bunch of kinks.

"There was a lot of balancing aspects that I don't think people fully appreciate that went into Achron," said Hazard.

I spoke with Hazard while on a business trip recently, and already filed a story on the game's 10 years of development and involvement with our nation's military (no, our government doesn't have time travel), but part of our conversation never made it into the story. Hazard watched our Quick Look (it's below) and read the comments from all of us--including you.

He wasn't upset, since many of the observations had been echoed elsewhere before. Instead, he started explaining the reasons behind them.

One of the basic decisions we puzzled at was having to select all your units simultaneously to chronoport, letting you warp across the map, rather than just telling the commander to do so, as in other games.

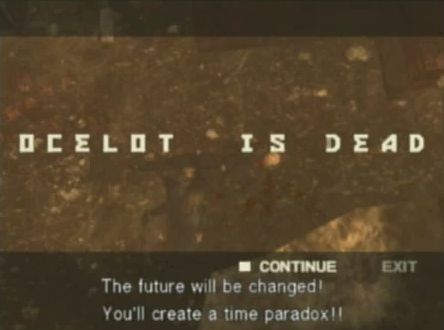

"You wouldn't believe the amount of balancing and thought that went into that simple decision," said Hazard. "You can send something back in time, and now, if you wait until the arrival--let's say the arrival was a minute ago--if you wait until that falls off the timeline that was committed into the past and now you undo the departure, now you end up with a permanent clone of that unit--a permalone, as we call it."

But if movies and books have taught us anything, clones (and paradoxes) are an intrinsic part of time travel. Hazard didn't want to erase it, only to ensure cloning didn't break the game and make Achron an interesting experiment, rather than fun to play.

"Early on," he said, "we knew this would happen and we had a whole bunch of tools to mitigate it, but we didn't want to break that mechanic because it's so consistent in our engine, so we wanted to come up with economic ways to mitigate that."

In Achron, players are responsible for actions in the past just as much as actions in the present, and are often flipping between the two in order to achieve victory. The game keeps time travel abuse in check through a resource called chrono energy and eventually cutting off how far back you can go.

Another issue raised has been the inability to undo certain actions, such as building a unit. Once you've asked a building to create a unit, you're stuck--unless you head into the past before it happened. If players could create and undo at will and also jump back and forth through time, it would break the game's engine. Back, forth, back forth, back, forth--woops! Crash.

"There are quite probably literally hundreds of little things that we've had to solve like this," he said.

Here's another head scratcher: factories within Achron cannot create units significantly more expensive than the factory itself, if that unit has the ability to chrono port.

"If you do, the person will take another factory, build the unit, send it back in time, destroy the factory, and now get the unit for free--if they time the way the paradox falls on the timeline properly," said Hazard.

The one exception is the mech's ability to create a carrier--but carriers cannot go through regular chrono porters, a solution that came to Hazard in the shower after he'd nearly given up on carriers being in the game.

"Making a carrier...if anyone's taken a single semester of a computer science course, you make a container, you throw stuff in it--that's easy," he said. "Stupid simple. Given the constraints that we're faced up against, that was extremely difficult."

These limitations were driven by the endless rabbit hole that is time travel. And while time travel is the feature that makes Achron largely unique amongst its peers, it makes it terribly difficult to grasp for players used to more traditional real-time-strategy games.

Hazard's explanations aside, Achron is not a perfect game, but if there's anything I learned from my 45 minutes talking to Hazard, almost any criticism of Achron is something he's already thought it through a million times.

If only Hazard could go back in time and give the 1999 version of himself all of this information.