(I'd recommend at least checking out Warbler's Nest before reading too far. It's free, and will take less than an hour!)

Playing a text adventure sounds easy. (At first, definitely not.) Type actions, then watch them play out. (Or, often, no.) It’s not that simple, though. (Correct.) There is not an actively learning artificial intelligence driving the on-screen text--it was all written by a person. That person is tasked with a hugely daunting task: predict all player behavior.

In a game full of shooting where you cannot open random door X, that’s no big deal. It’s a game about shooting, so you can go around the corner and keep shooting. Plus, in most games, players today are expecting a sense of linearity. Not so in the text adventure, which explains why things like this exist for beginning players. It’s all about exploration, and that requires the designer to have answers prepared to all your poking and prodding.

Say, for example, you enter a room, you’re told your Grandpa is sitting in a chair, and you type:

push grandma.

Now, why would the player push Grandma? First, who does that? Second, the game said Grandpa. Part of a text adventure is learning the limits of the adventure, and the player has to, at first, explore all of their boundaries.

“You can type whatever you want, and most of what you can type causes absolutely nothing to happen,” said Jason McIntosh, designer and author enjoyably creepy text adventure Warbler’s Nest.

McIntosh also had the honor of introducing me to the text adventure. Yes, a shameful secret revealed. Having played Warbler’s Nest, though, I’m now psyched to see what else the genre has to offer, especially since it’s hardly a dead one, which was certainly a surprise to yours truly. Sure, the text adventure isn’t getting a billboard in Times Square these days, but devotees of interactive fiction, the fancier term for the text adventure, are keeping the genre alive. McIntosh is one of those people.

(I’m about to spoil some parts of Warbler’s Next, so if you want it to remain a mystery, play and come back. It’s free!)

Warbler’s Nest is McIntosh’s take on the changeling myth from Western Europe, a tragically real belief from the 19th century wherein parents came to believe their child had been kidnapped and replaced with the child of a goblin, troll, or other creature. These days, we’d come to understand these children were developmentally disabled, diseased, or suffering from some other disorder. This wasn’t understood concept back then, so the parents would go to great lengths to get their children back, including drowning the children, placing them into a heated oven, and other horrific acts.

It’s easy to look back and scoff, but in the absence of science, imagine being a parent who believed their child had been kidnapped, and this child-like thing left behind was not theirs. Often, McIntosh noted, there’s a reference to a friendly tailor, a confidant who advises what to do. In this case, collect...eggs. (It's also part of the myth.)

“Wouldn’t it be really disturbing to have a short video game where the player character is the mother of a baby during this time period, in this setting, and has no reason not to believe this is a thing that happens?” he said. “Could we make a game about the decisions that you would have to face, and her reality, without making it a fantasy story? Setting it in a realistic setting, but making it about the way that her sense of reality projects, if you will, onto the world around her, and makes this unthinkable thing real to her.”

The original idea bubbled to McIntosh while exploring a museum full of pikes and swords in Boston, and he soon began researching the concept of the changeling. At roughly the same time, he had started regularly listening to the amateur horror fiction podcast Pseudopod, despite not caring for the genre, and playing through ACE Team’s Zeno Clash, an unsettling first-person brawler with a similar sub-plot. He admired that game's sense of place.

“It takes reality, turns it by two degrees, and then follows that down a path,” said McIntosh.

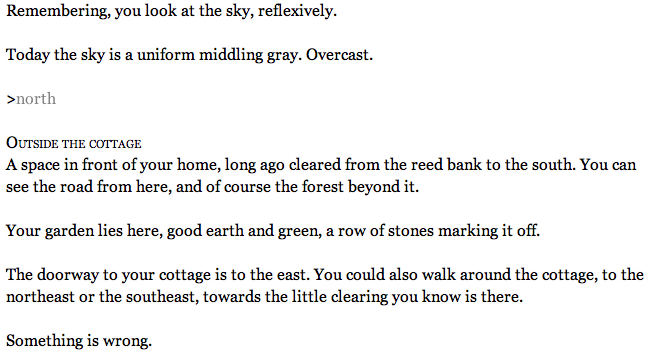

The changeling angle isn’t revealed up-front in Warbler’s Nest. Instead, the game simply alludes to something horrific inside the main character’s home. Here’s an excerpt from the very beginning:

It’s eventually revealed that “something” that is “wrong” is your child. The scene inside your home, the crux of the story and gameplay, is the first scene that McIntosh started piecing together, right around the time he was playing Zeno Clash. There’s a baby in the room, and what happens next is up to you. There are multiple ways for this scene to play out, and it’s where McIntosh got incredibly playful with the interaction between player and creator.

“If you type in a violent action,” he said, “if you type in ‘hit baby,’ or ‘cut the baby with the shears’ or whatever, the player will not carry out that action, but you have now permanently darkened the game because the attitude I wanted to present was ‘Oh, that’s the game we’re playing? Okay.’”

This is a case where experimentation can backfire on the player, depending on how they “wanted” the story to play out.

“That’s how you get to the ‘bad ending’ and the player character starts to believe maybe the tailor was right,” he continued, “maybe this actually isn’t my baby, and it starts to fill in this past where it’s actually suggested that maybe the mother has tried hitting the kid in the past. This does not come up if you do not do that. I wanted to make it very unsettling. If you treat the child with affection, it goes the other way.”

If you treat the child with affection, it's implied you accept the child as it is, changeling and all.

This scene is also where I had the most trouble with the game, unaware of what language to use. As someone without much text adventure experience, it was easily most frustrating part of the experience. Relative to modern "standards," a term I use rather loosely, the game is providing precious few drops of feedback. (I also realize this can be, and this case is, a very good thing. It's just different.) But for every moment of frustration in Warbler’s Nest came one of extraordinary euphoria, as I discovered the phrases that unlocked the next area, the next piece of story.

Juuuuust often enough, though, when I was typing ideas that didn’t accomplish anything, the game was had a piece of useful feedback in response or a new slice of plot to keep my interested, a testament to McIntosh’s extensive playtesting. Playtesting a text adventure game in the modern age is easier, as players can simply send along their entire transcripts, and the creator can make adjustments based on how the game did or didn’t respond.

“The only way to make a game that’s actually playable by people who are not dyed-in-the-wool IF [interactive fiction] fans is to have a lot of people test it, and find a whole lot of paths that don’t work and spend a lot of time,” he said.

McIntosh figures probably 50% of his code is spent simply responding to potential behavior that has nothing to do with the path he wants players to go down, but will hopefully nudge them back to it. It’s this struggle between explicit and implicit that underscores what McIntosh loves about the genre.

“Why I like it so much, both as a player and as a developer, is that specifically in how it lets you play with ambiguity and, to a great extent, the game I created is about ambiguity,” he said.

By the end of our conversation, there was an itch, and McIntosh helped me scratch it. Ever since the MolyJam came and went earlier this year, I’ve talked about how developing a video game, even a tiny, dumb one, would be a useful exercise. Since I’m so used to writing for a living, why not start with a game that’s entirely word-based? A big reason the text adventure remains a viable genre, McIntosh told me, is specifically because of the software that makes creating new stories so easy, a testament to the community.

McIntosh recommended would-be creators to download Inform7, a free download at www.inform7.com, and read the Aaron Reed’s Creating Interactive Fiction With Inform 7+. The book guides you through creating a sprawling text adventure using Inform7. Inform7 even has the ability to spit out a Javascript version of the game, which means you can dump that into Dropbox and, voila, anybody can begin playing your probably not great game on the web!

I’d had ambitions of creating something small and stupid to be released alongside this article, but so far, all I’ve done is drag Inform7 into my Applications section. Status quo achieved!

The best thing you can do, though, is play loads and loads of good text adventure games, and soak it all in. Fortunately, the Boston-based group McIntosh is part of, People’s Republic of Interactive Fiction, has a list of must-play games that’s constantly updated on their website. That seems like a good place to start for you and me.