The Witness provides further evidence that video games are approaching the same degree of authorship as more traditional forms of media, in the sense that Braid players will immediately recognize this as another game made by Jonathan Blow. Both games offer devilishly, sometimes painfully tough puzzles built around detailed logic systems that you're expected to intuit and employ with next to no guidance. Both have the uncanny ability to alternately make you feel like a genius and an idiot. Both games tend toward an austere style of philosophizing that can come off as heavy handed or self-indulgent, but which nonetheless seems to flow directly from the individual consciousness of their creator. The Witness matches and then surpasses the exhilarating a-ha moments of Braid's most unconventional puzzles, while also one-upping the simple, discrete platforming levels of Blow's previous game with a sprawling world that's as impressively interconnected as it is starkly beautiful and laden with secrets.

This game has been dogged by comparisons to Myst throughout its production, but the comparison is so apt that it's hard not to use that old CD-ROM standard as a starting point. The similarities are overt--again you're a nameless, wordless protagonist exploring a deserted island full of bespoke contraptions and no small amount of mystery--and also tonal, with a softly brooding atmosphere punctuated only by your footsteps and the wind. But the way you engage with the world of The Witness is more focused than Myst's legion of various levers and dials, since all of your interactions with the game come in the form of maze-like line puzzles displayed on screens dotted all over the island. Hundreds of them. There's no inventory, no physics objects to play with, no jumping or even stepping off of ledges. Just panel after panel after panel to complete as you peel back the many layers of the island's intricate secrets.

But The Witness is much, much more than just a series of standalone logic puzzles packaged up in a pretty graphical wrapper. Ferreting out the nature of the many different types of puzzles that exist on the island--how their individual rule sets work and interact with one another, what effect they have on their surroundings, and in turn how their surroundings can affect them--is 100 percent of what there is for you to do in this game, and the extent to which you have to really work for many of the solutions can be exceptionally gratifying as you fumble and reason your way through the game's many hours. As such, ruining any of the surprise about how these things work would do a disservice to the people who are really going to enjoy this game, so I'll try to be vague in describing what's in here, and I'd encourage you to read and watch no more about this game than you need to decide if you're interested in playing it.

The game never offers a word of explicit tutorial, instead loading you directly into the game world and turning you loose to explore and learn and solve. Most of the island's distinctive areas offer a relatively simple starting set of puzzles that "teach" you the puzzle rules that apply to that area. In practice, the game doesn't spell anything out whatsoever. You learn entirely by doing, and the sparse information you can glean from the trial and error of figuring out the starter puzzles is immediately useful in some cases--allowing you to go forth and apply what you've just learned to more complex problems and push forward in the game--but agonizingly unclear in others. In a couple of spots, after being stuck on more complex later puzzles for hours, I had to return to earlier similar puzzles and simply stare at them, asking myself questions about how they worked and what sorts of pieces they were made out of, before the lightbulb flickered on and I could progress.

But the lightbulb moment is why you play this game. It's certainly possible to overthink what it is the game wants out of you--in a few instances, I eventually realized the puzzle I was trying to solve in my mind was harder than what was actually in front of me--and in general, the puzzles in each area are consistent about adhering to the theme of that area, so frequently, you just need to stop and focus your thought process. The iterative nature of the puzzle design, the way subsequent harder puzzles build on the concepts and lessons you've already absorbed--not to mention the specific, nearly hint-less environment in which I played the game--often made me realize that I was actually capable of solving harder problems than I thought I was, if I just invested a little more time, modified my approach, and focused on different concepts or details. At those moments I had to consciously stop and ask myself what I could do differently (and I could actually feel myself suppressing that impatient urge to just run to the Internet for help), which actually felt like a fun little voyage of self-discovery. Absent any sort of guide or hints, you'll have to think, a lot, to put some of this stuff together.

The puzzles run a fairly even split between two distinctive styles. Many are abstract problems that operate entirely on their own self-contained logic--typically signified by various colored symbols that appear directly on the maze screen--and feel like the sort of thing you'd see on a standardized aptitude test. Then there's a more organic style of puzzle that often requires you to look and think outside of the maze's borders to the larger game world to hit on a solution. Sometimes these two types of puzzles mix and overlap. Sometimes they subvert or seemingly break their own rules. Absolutely everything about both the puzzles and your surroundings is in play, from your perspective to the lighting to the type of input method you use. You learn very quickly that you can't necessarily take any detail in this game for granted, no matter how minor it might seem. That uncertainty creates a profound mystique, a feeling that anything could happen on this strange island where the rules of reality are more than a little flexible. It's hard to convey the range of creativity in the more complex puzzles and the way they integrate into the game's world without diving into a lot of specific examples, but the range is significant. It's the kind of thing you get really excited about and desperately want to share or discuss with other people when you see and solve it. It's great stuff.

The Witness didn't need to be a beautiful game for most of its important parts to work, but it sure doesn't hurt that the island is exceptionally gorgeous. The art design takes a profound less-is-more tack, building a world out of simple geometry and sparse texture mapping, and instead focusing its attention on a strong use of color and lighting to bring out a significant amount of organic detail that's too exaggerated to be called realistic, but also stops short of becoming cartoonish. This saturated, brightly lit aesthetic repeatedly brought The Wind Waker to mind, which is about as respectable a comparison as you can make in my book. The game also seems to use the trick (one that I first remember making the zones in World of Warcraft so moody) of subtly shifting the color grading as you cross the boundary between regions, so that you rapidly get the feeling you're in a different place than the one you just left. That's a handy trick to have in a relatively small land mass that jams desert, swamp, ice, mountain, jungle and forest locations all together in close proximity. And again, the visuals aren't just for show; so many of the presentational aspects play into puzzle solutions and other secrets in clever, satisfying ways. Once again I'm sitting here wondering if I should drop a couple of neat examples to illustrate the point, but no. That stuff is too much fun to discover for yourself.

While everyone is free to play games however they want and I wouldn't begrudge anyone who wants to follow a guide and just see what this game has to offer, I got a tremendous amount of satisfaction out of exploring The Witness prior to release, when no hints were even available. Playing The Witness in a vacuum--and feeling the occasional frustration and desperation that come with sometimes not knowing what the hell is going on--acts as a nice counterpart to the solitary feeling inherent to your time alone with the sometimes stifling quietude of the island. I can think back on a handful of puzzles whose solutions felt a little clumsy, or where I came away not exactly sure how I solved what I just solved, but the vast majority of the puzzle solutions are some satisfying mix of inventive, elegant, and clever that made me absolutely delight in working them out myself.

All that said, I highly doubt I'll ever figure out everything myself, and I envision a rabid community effort getting underway to plumb all of this game's deepest secrets--and there are some that seem to be buried really deep--shortly after release, much like what happened with Fez. The Witness doesn't get quite as crypto-crazy as that game did--you aren't going to be deducing an entire system of writing or anything--but a lot of what there is to find and solve in this game is in the same spirit. To be fair, there were a few puzzles that simply left me to yell angrily at the television and confer with a couple of similarly confused other reviewers before I finally got what was going on hours or even days later. Serious frustration is inevitable in The Witness, but in the era of ubiquitous walkthroughs and video guides, I can't really fault a puzzle game that goes to the occasional extreme. If you enjoy the sort of game where you frequently place your brain on an anvil and then hammer away at it until you either break it or forge a deeper understanding, you'll find a whole lot to like about this game.

Much has been made about the length of The Witness, and all that ballyhoo isn't for nothing. It's possible to see an ending of sorts after probably two or three dozen hours, but reaching that ending only requires you to solve a little over half of the game's numerous regions (though ironically, if you don't at least dabble in the types of puzzles in a handful of specific regions, you'll be ill-equipped to finish the game's brutal final area). Once you exit the tiny starting courtyard, the only thing gating your access to every nook and cranny of the island is your own knowledge, and you're free to solve whichever of those regions in whatever order you want. In practical terms, some of the areas are dramatically harder than others--and indeed some of them require you to learn the lessons of other areas before they'll even make sense--but it's easy enough to traipse back and forth between puzzles in different areas whenever you get stuck, so your path through the game will undoubtedly feel more organic than simply knocking down one area wholesale before moving on to another.

On top of what's required to "finish" the game, there's also an almost baffling number of other puzzles to tackle in this game that seem to have no bearing on the main campaign, as it were. The game is constantly teasing you with other sorts of less conventional puzzles and hidden areas that don't fit into the familiar categories you've been working with, and frankly after probably 40 hours in The Witness I still don't know what the hell a lot of those puzzles do at all, nor how to solve them, nor how to open up quite a few of the optional buildings, caves, and passageways that I passed over when I first saw them. Without saying too much, the game also contains what might be my favorite take ever on the video game collectible. If you were to do all this stuff yourself without just looking up a guide to breeze you through it, I have no problem believing that 80 hour figure that's been floating around to be roughly accurate. The hindsight of having "finished" the game, and knowing how much more there is left to do, makes the recent hand-wringing about the game's $40 price tag seem especially absurd.

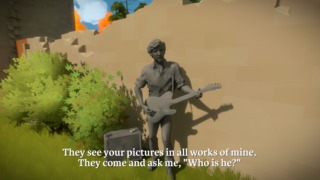

If you're wondering why there's no mention about any sort of story in this review, well, there isn't any to discuss, really. Braid told the personal tale of a failed relationship--and the inherent biases of the people involved in it--in deliberate fits and starts that made you reflect on what it was you thought the game had been trying to say by the time you finished it. The Witness is way less focused by contrast. It's best described as a loose meditation on epistemology and spirituality (not to mention literal meditation), which takes the form of a bunch of stone statues scattered around the world that pantomime exaggerated actions, and voice recorders that rattle off quotations from various scientists, religious figures, and other thinkers throughout the ages. A couple of the quotations resonated with me on an individual basis--there's a touching Apollo astronaut's soliloquy that feels extra urgent in the context of the present day--but the ideas as presented are too scattered to form much in the way of obvious thematic intent, and more than once I was left thinking "OK, and...?" after listening to one of the lengthier voiceovers.

Your interpretation of this stuff--or indeed, how much you even care about it--will largely depend on what you yourself bring to the game, and if you're feeling especially snide you could certainly dismiss it all as overly artsy or trying a bit too hard. For my part I wasn't really put off by what the game was going for, despite sometimes feeling like I was being bludgeoned with a philosophy textbook, and all that quiet reflection certainly gives the game its own specific feel, for better or worse. Actually, the worst thing you could say about this stuff is that it's easily ignored (you don't even have to activate any of the voice logs), and given everything else The Witness does marvelously well, it's not hard to forgive it when its more self-indulgent tendencies assert themselves. As much as I hate myself for saying this game is more about the journey than the destination... well, it is.

It's hard to believe nearly eight years have passed since Braid came along and helped elevate ideas about what smaller indie games could be, and while I don't think I'd say any game is worth waiting eight years for, there's also not a whole lot I'd change about The Witness or the time I spent with it. Slowly and deliberately exploring this resplendent island, picking my way through its elaborately constructed secrets, and occasionally bathing in the warm glow of revelation all cohered into a singular experience I'm not going to forget, or even stop thinking about, anytime soon. The Witness isn't just an example of how video games can be similar to other creative works; it's also a great reminder of the special things only games can do.