(If you have not played The Walking Dead: 400 Days, do not read this. Spoilers abound!)

It’s taken far too long, but Faces of Death has returned.

For the newcomers among us, when Telltale Games released each episode of The Walking Dead last year, I’d spend an hour on the phone with the talented individuals behind the horror. These are spoiler-filled affairs, as we’re walking through the thought process behind each moral quandary.

The Walking Dead: 400 Days was released a short time ago, and served several functions. It’s a teaser for the next season, scheduled to kick off sometime later this year, and to remind people the series is still alive, kicking, and trying out new tricks. Rather than expand upon a side character from the first season or explore a lost plot thread, Telltale spun a series of short stories that introduced and dispatched characters as quickly as they appeared.

Some of it worked and some of it didn’t. It did produce the first moment where my wife, who makes the decisions in our playthrough while I hold the controller, refused to make a judgement call. You spend just enough time to get to know and empathize with these new faces. 15 minutes felt painfully short for how much more could be explored, and even if we never see these characters again, it was fun to stress with them.

Designer Sean Ainsorth, writer Nick Breckon (yes, that Nick), and writer/designer Mark Darin took some time to chat with me recently, and here’s the entirety of our conversation. Sadly, the audio was not good enough to produce an accompanying Interview Dumptruck, but I hope to continue this feature into season two of The Walking Dead, and we’ll make sure audio happens.

- Faces of Death, Part 1: A New Day

- Faces of Death, Part 2: Starved For Help

- Faces of Death, Part 3: Long Road Ahead

- Faces of Death, Part 4: Around Every Corner

- Faces of Death, Part 5: No Time Left

--

Giant Bomb: What did you want people to come away with when the credits rolled?

Sean Ainsworth: When we originally sat down and talked about it, we thought it would be really interesting to do something that wasn’t season one. That was our main goal at first. We didn’t want to completely differentiate it from season one, but we want people to come away with a new thing, you know? Those were the things that, when we initially started talking, we were excited about. It’s the idea of “okay, I guess we’re going to do DLC, what is DLC?” And trying to make something that made sense, instead of something that was tacked on to season one.

Mark Darin: We talked a lot about what DLC would be, and when we were approached for just doing an extra episode, and we talked about “is this just going to be another episode? Are we going to spin off a story of one of our side characters?” It never really felt like it was good enough and in service to the franchise. We really wanted to do something that felt like it was worthy of a standalone episode, something that was different but very, very much in The Walking Dead universe. We knew we weren’t going to have time for a season, and building up the character relationships like we did with Lee and Clementine, in just a single episode. With that in mind, we brainstormed “what is going to make the most sense for a single episode, when we can’t build those kind of relationships?” We came up with the idea of telling short stories that would, instead of building really strong relationships, should have the time to build relationships with the character and quickly force you into those grey, moral dilemmas. Putting those people in the mindset of “what the hell would I do in this situation?” and being able to present them with a lot of different kinds of those situations. That became the most appealing thing to do within this Walking Dead universe that we could do in a single episode. Still make it really feel like that Walking Dead experience that you got in season one [but] really compacted into these short stories.

"We looked at it as a little bit of an experiment, too. How quickly could we make somebody feel like they would care about this person?"

Ainsworth: To that point, we looked at it as a little bit of an experiment, too. How quickly could we make somebody feel like they would care about this person? How quickly can we put somebody in somebody’s shoes--the player in the character’s shoes--and have them make decisions that are actually meaningful to them? In that way, we really were interested in exploring new ways to do the sort of things we did in season one.

GB: What proved to be the biggest challenge in build these relationships and the characters, so you can produce some manner of empathy when you get to the big moments?

Ainsworth: [laughs] We had a lot of challenges there, actually. We had to figure out our baseline for how long a chapter would be in the episode. That was the first thing. We talked about five minutes, we talked about 10 minutes, 15, half-an-hour. What was going to be the amount of time that you had? We eventually settled on 15 minutes, a good way to sit down and figure out exactly, “okay, we have time to set this up, we have some time to meet people first, and then we can throw the decision at you. Or we can throw the decision at you up front!” We talked about it a whole bunch of different ways. When do we introduce this decision? Do we do them all at the end? Do we one at the beginning? Can we do that? Can we just throw a decision right at somebody right off the bat? We found out the answer was no. [laughs] Those were the main things. People were coming to expect those decisions from The Walking Dead, so we thought “okay, well, how long can we go before we get to one of those, before it gets interesting?” After a lot of discussion--we had a lot of discussion about it, I remember it--we came to 15 minutes.

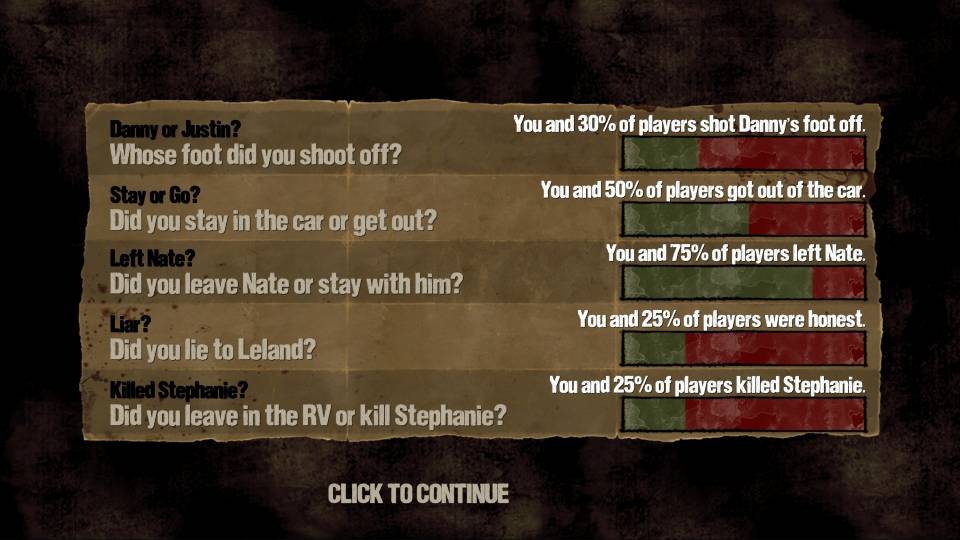

"Whose foot did you shoot off?"

GB: When I encountered that moment, it certainly felt like there were some echoes of the axe chopping moment at the beginning of episode two in season one. Was that a conscious decision, or was that my own projection onto that horrifying scenario?

Darin: There was a little bit of consciousness there about that. I don’t think it was specifically a conscious effort to mirror that. They are similar but different enough where each situation stands on its own, but can subconsciously call back to one and have you reflect on what you did the first time. How is that going to make you feel this time? We knew that, but it wasn’t really built in; we knew people had experienced these things but we really wanted to focus on getting you into that situation where you get to know a couple of characters who are really unsavory guys. But both have good points and both have bad points and you get to know them as people. You first kind of know them as their stereotypes and how their crimes are, and what your interpretation of what their crime is. We give you a little bit of time to get to know them as people, allow you to reassess how you feel about them based on that, and then we jump into some action and give you a third way to judge the characters, based on their actual actions. Then, using all this information, put you in a situation where you have to make a choice and the choices really have to be reflective on the things that have built up specifically in this episode and try not to rely on your past experiences so much. But as far as The Walking Dead world, every experience that you had is on your mind coming forward, so we were conscious of that, but it wasn’t built into the design of that moment.

Ainsworth: We initially talked about this as a standalone episode, a completely standalone episode, when we were originally talking about. Then, we decided to make it DLC, and we could tie it in from season one to season two--but you can play it or not. When we were originally talking about it being its own thing, some of those decisions were “okay, well, you didn’t play season one, so we couldn’t build it that way.” We tried to build it in a way that if you played season one, those sorts of things could enrich [it], you could definitely see echoes of things that happened in season one. When you see someone like Becca, who’s kind of a Clementine-ish figure. Not really, but we tried to differentiate her as best we could. But you can see the links to season one in that way. Here’s a different situation, but the same sorts of emotions are going through it. It was important for it to stand on its own. You can play episode one of season one and then skip 400 Days. You even just have to own episode one, and you can play 400 Days right off the bat. It had to stand on its own.

GB: The reason it echoed for me was because when you actually do pick somebody and it’s time to pull the trigger, my first thought was “these assholes aren’t going to let me do this once, they’re going to make me pull this trigger twice.” Then, of course, I had to pull the trigger twice to get the leg to blow clean off. How do you decide on...twice?

Ainsworth: It was really more down to the...the way that the puzzle, if you want to call it that, was designed, was that you were trying to get at the cuffs and not at the leg. If you’re aiming at the cuffs, the leg is going to absorb some of the impact. You have to shoot it again because it didn’t work the first time, but that’s just a side effect. Blowing the foot off is a side effect of actually trying to get the cuff off the guy’s leg.

Nick Breckon: We just really wanted that moment to feel very punchy...just gruesome. That choice was always about taking a blue collar guy who denies his crime and having a guy who has committed a white collar crime and is specifically admitting that he’s done it and allowing you to make that choice at the end. We didn’t want the player to get away with having that be an easy choice.

Darin: The first pass of design actually was a single shot, and we tested it, and that single shot wasn’t enough time for you to absorb what you’ve done before the thing ended.

Breckon: Right.

Darin: You didn’t get to sit in that moment with the guilt and, then, being faced with having to continue through it. To have the player really be able to absorb them, we have to have those moments where you have time to do it, and that’s where you evaluate “is it one shot or is it two? Is it three? How much time do we need for you to absorb what the horror of what you’re doing is and contemplate, ‘maybe I shouldn’t have done it? But now it’s too late, I have to keep going with it, I’m this far in it already.”

Ainsworth: You have a plan and that plan doesn’t work. What now? Well, I have to keep going! You just have a couple more seconds, and those zombies are pounding on the door, trying to get in.

Did you stay in the car or get out?

GB: I stayed in the car because it seemed like leaving would be crazy. When I’ve talked to you guys in the past about these sorts of moments, it seems like the big challenge is trying to make sure that you’re coming up with moments where the writing reflects that both choices are viable. At least, trying to make an argument in for both of them.

Ainsworth: If you’re in that situation, I’m always trying to think about as many things that somebody would try and do. You’re never going to figure them all out, but you kind of look at it from the character’s perspective. Who is this character? What were they thinking? And you marry those two together, which I think is really nice when it works out. It doesn’t always work out. When you have a choice like that, there’s no way I’m going to walk through this dark foggy road and try and look for this guy who I’m not even sure is a human being. There’s plenty of people out there who are going to say “no way, buddy!” You gotta make sure that’s there. There are some other people who are gonna go “alright, I’ll go!” It all boils down to what the scene is.

Darin: Something I found interesting in the episode was Wyatt. What was really experimental for us was that you, as a player, could really push hard either way to try go out or stay in the car. You can force it, but you really had to push. The premise around this episode is your fate is left to a game of chance. That was very experimental for us to try, and it came down to a game of rock-paper-scissors. It really is just chance, and it’s fate imposing a chance upon you and how you feel about that, as a player, character, and a person in that situation. Are you okay with putting your faith up to chance, or are you going to push really, really hard to one side or another to try and maintain control of that? For me, that was one of the exciting, more experimental things that we were able to do in the DLC. We wouldn’t have been able to put that in season one or a regular season as easily.

Ainsworth: We probably pushed it a little too hard--Eddie pushes a little too hard.

Darin: But he loves rock-paper-scissors! [laughs]

Sean: He really wants to play rock-paper-scissors.

GB: With some of the choices, the consequences are pretty immediate, and someone dies in the most extreme cases. In this case, you make your choice and it’s not really clear what happens. Here, you’ve left him behind, but there’s a lot of ambiguity for the player about what the result of that choice is.

Darin: For me, that was an important part of the way we were structuring these stories. We knew were only getting 15 or 20-minute chunks, and we weren’t going to have the space to explore what happens next, although we wanted to give you enough information and enough narrative meat to really think about what it is that’s happening. What would I do in this situation? And then continue to ponder that after the chapter ends. You don’t really know where it ended up, but you have a pretty good idea where it’s heading, and you can finish the story on your own. It’s probably very similar to what would actually happen. We don’t need to give you that closure. Plus, we can leave some of it open to interpretation and allow discussion between people about what they think would happen. I think that is a really interesting thing to leave with players.

Ainsworth: It’s really interesting to watch the way people react to it. We have a certain idea about what might happen, but it’s not necessarily the canon idea until it is. It’s really interesting to hear people discuss it, and the interesting thing, too, is that life is messier than that. You make a decision, and you may not see the ramifications of it for a very long time or never. It might affect somebody else, but you might not see those ramifications. It feels a little truer to life.

Breckon: I think the way that we approach choices that I find interesting is that you don’t always have that immediate result, which is often a very...it allows for the domino effect of life, the chaos of it, to come to fruition in a way that you wouldn’t expect, which is not exactly what you would do if you were just sitting down and thinking about “well, we’ve gotta have X and it has to branch A or B.” But if it can go down the line and do that in a way that is more interesting and the less rote, I think that’s always better.

Ainsworth: I feel like those are the most interesting stories to me, the ones that aren’t exactly a pat narrative. You don’t have the one-hundred percent “oh, this happens in act one, this happens in act two, this happens in act three--these things are all causal and everything is related.” What’s most interesting are the ones that have that room to breathe and we try pretty hard to make that part of the game.

Did you leave Nate or stay with him?

GB: With Nate, you’re kind of just writing a complete asshole. From your guys’ perspective, is it fun to write those characters who are, I would hope, completely different than your own personalities? How do you get in that headspace, when you have to write a guy like that?

Breckon: [laughs] That chapter was written by Sean Vanaman, and I know that he based that one a character in his life that he knows personally. But also, everybody, in writing characters, you identify elements of them that either you picked up in life or just elements of yourself that you can take to an insane degree that you wouldn’t as a person. I definitely picked up a few lines in there where I said “oh, I think Sean would say that if he was just really drunk.” [laughs] That’s what so great about Nate. He feels very real to me, and I think that’s what Sean [was doing], basing him on somebody that he knew.

Darin: But writing for somebody like Nate or Larry, it’s always the best. You really get to go out and write the best lines for those characters, they can get away with things that the other characters just can’t. You can pour yourself into it and have fun with them.

GB: It seemed like with those two characters in particular, Nate’s the kind of guy that’s just embraced the chaos and does whatever he wants in the world, whereas Russell, maybe to an extreme, is naive and wants to remain pure. It felt like they were very distinctly setting up those two polar opposites, so that when you were confronted with choices, it made it very surprising when you had someone like Nate be try a bit of a protector.

"In writing characters, you identify elements of them that either you picked up in life or just elements of yourself that you can take to an insane degree that you wouldn’t as a person."

Ainsworth: Sean did a really good job balancing that, making Nate just crazy enough that he was on the edge but still human enough that you kind of trust him a little bit. You see where he’s coming from, at least. I think that worked out really well. And you need somebody like Russell, who’s a little bit more of a naive, blank slate kind of guy, to let that character bounce off of. Nate is way more interesting when he’s antagonizing Russell for being boring.

Breckon: I thought it’s really interesting, too, that they highlight each other’s differences. Thinking about Nate, Nate feels like the kind of guy that would play a game like GTA just, basically, killing everyone in the world, whereas Russell is the kind of guy that would be taken advantage of. [When you] just throw them together and have these two very different personalities, and let the player decide what kind of person they are, and view them through that lens. I think it’s interesting.

Did you lie to Leland?

GB: The whole scene in the field felt like the most like an old school horror film, kind of like the cannibals in season one. What were you guys cribbing from inspiration?

Ainsworth: You know, that scene actually, in its entirety, came out of Wyatt. Originally, when the Wyatt scene was written, when you stayed inside the car, you got chased into a cornfield. Some of the other stuff happened, but the cornfield started there. It was just something that was nearby to the road they were in, and it made sense for that moment. But it was way too big for that chapter. It was making it bigger than any of the other ones. We split it off and it ended up being where Bonnie’s story came from. That’s sort of where it was. I think, honestly, it came from E.T. more than anything else.

Darin: Once we had the cornfield and we knew it was going to be a thing, there were elements that were leftover from a gameplay standpoint from way back in season one, episode two, where we wanted to a cornfield chase and it never happened. This was a great opportunity to explore new types of gameplay that we didn’t see in season one, and it all just came together in a really nice mesh for this.

GB: For that scene in particular, a Telltale take on stealth, was that challenging to build? You essentially want to build it so the player gets to the other side, but you don’t want there to be any lack of risk the choices players are making.

Sean: Oh, boy.

Darin: A process of iteration of trying to make you feel the tension. It was a process of seeing what type of gameplay that the player could interpret easily while moving through the cornfield. We tried a lot of different concepts in prototyping and spatial relations. We knew the feel that we wanted, so just had to keep iterating on it until we hit that right spot that felt that you were in control, that you were hiding, it was adaptive, you didn’t spend a lot of time learning a new mechanic, and it didn’t fight the tone of what was going on. It was just a process of trying, setting up, seeing if it’s not working, and trying it again.

Ainsworth: We went through a bunch of different ways that didn’t work. [pause] Lots! [laughs]

GB: One of the moments that really sticks out is when you have the conversation with his wife after you’ve smashed her face in. The way the woman’s face looks really stuck with me after I was finished with 400 Days. How do you guys go about even designing and iterating on how a smashed up face is supposed to look?

Sean: Very little iteration on that one, man. The character artist just nailed it on the first go. We might have said “I think it’s a little too bloody” at first. That’s right. There was one minor iteration. It came back and it was too bloody. You couldn’t tell that her face had been caved in at all, so we said “pull some of the blood back a little bit, so that we can see that she’s severely damaged here.” And, then, the eye not moving was really important, too.

GB: The eye! The eye is the thing that stuck with me. I kept staring it at during the conversation. It was terribly unsettling.

Group: [laughs]

Ainsworth: Yeah. You knew something was wrong when you see that eye isn’t moving, right? That was really important. We have a couple of people in the studio that I feel really sorry for, they just have to keep staring all kind of traumatic from life images of people who are just horribly, horribly damaged to recreate some of the stuff that we put into these games. They’re doing it to these quasi-cartoonish characters, which makes it a little bit easier, but even so, some of the references they have to look at is...I don’t envy them.

Darin: I’m with you.

GB: But it must make it a lot of fun when you come up with these things, and you have to say “alright, go figure this out, not my problem anymore.”

Group: [laughs]

Ainsworth: Well, you explain what you want. The horrible thing is when somebody work on it, and then you see it and then you go “man, can we make this bloodier? Can we mess this up even more?” You feel like a horrible human being even talking about “there’s not enough bristles.” Things like that. It’s an odd thing to be doing for a living, but it’s awesome.

GB: This choice, in particular, was a stressful one. How much are you guys considering if the player is making that choice based on what they think they would do in that situation or what they think the character should do in that situation?

Ainsworth: Ideally, you want the player to be making the choice. You really want the person with the controller or mouse and keyboard in their hands to be the ones who is stressed out. There’s so many different reasons that can be the case that if we just set up those empathetic moral quandaries well enough, people will just do that inherently. They have that empathic response, they want to help this person out. Some people don’t play that way, which is totally fine, but that’s just the type of person they are, the way that they view that choice. It’s about the character and whether or not you relate to them, which is key. That’s the important thing.

"You’re never going to be in a situation where what you want to do is completely against what the character wants to do. If that happens, we’ve designed it all wrong."

Darin: We put a lot of thought into that question. How much is it character motivated and how much is it player motivated? From the start, we have to think about these things together. These things have to be something that comes out in the experience and are part of the design of the character. The character has their own motivations, but the character is also carrying your own motivations and what you would do in this situation. There’s a lot of thought that goes into building the nuances, so that we have the room to say “this is your character, this is your character’s experiences, you’re also bringing your own experiences into this. You can have the room to play whatever way you want to, whether it’s best for the character.” You’re never going to be in a situation where what you want to do is completely against what the character wants to do. If that happens, we’ve designed it all wrong. We have to re-design a situation or re-frame the situation, so that you and your character know where you stand in the world and your choices are similar enough that you have some room to play it the way you want to and play the character the way you want to, but it’s still you and it’s still that same character. You’re still going down a path in a certain direction. It takes a lot of work.

Ainsworth: [laughs] There’s no way to know who’s going to play the game. Whoever you are, you’re going to bring all sorts of stuff to the table. Our job is to make that transition easier.

Darin: Sometimes, writing a story and thinking about character motivations, that gives you a great story but it doesn’t give you a great game. That’s a balance we have to find.

Breckon: From a story perspective, it’s about finding the range in which that character would make a choice and making sure that, either way, it’s believable, based on what has occurred prior. That character could go either way. No matter how the player feels at that moment, you want it to feel like a story that is cohesive.

Did you leave in the RV or kill Stephanie?

GB: I enjoyed this quite a bit, especially contrasted to the rest of them, because it did feel like it had the most room to breathe. It was one of the few ones where you could walk around, talk to people, and get a sense of place. For putting that together, was that a breath of fresh air?

Darin: It was a conscious decision. We had known the pacing of the chapters that you were going to play, but we also knew that you could play them in any order, so we couldn’t control that pacing as tightly as we might otherwise. Knowing there were chapters like the prison bus, where it’s just beat after beat after beat, we were conscious that we needed some time to open it up and be able to explore and have some of the other types of gameplay that are represented in The Walking Dead. We tried to really balance it out and make sure that everything was represented, and give you that breath of fresh air that isn’t quite as fast paced. It was important to have that element there to balance it with the other ones that were part of the spin-up of each of the other chapters.

Ainsworth: From a pacing standpoint, it was super important to have a quieter chapter. We also wanted to see if we could do one that took place over a longer period of time. Most of these, being short stories, there are so many different types of short stories you can tell. A lot of these are very quick, they’re about one moment or they’re about several successive moments. But that chapter takes place over a fairly long period of time, and it’s about consequences over time. You actually get a few choices in that chapter, it’s pretty cool. You can see how they play out.

Darin: I do think with some of that chapter, I was expecting people to carry over their thoughts from season one, and played with some of those expectations a little bit. When you saw Becca and you instantly had this Clementine connection, and you think “I know how to play this. This is my Clementine.” And then really quickly you feel “oh, it’s not Clementine. How am I going to react to this person? This is not the same situation. I have to readdress how I think about this situation.” You don’t need to have that information from season one, but if you did, it really changes how you came into the chapter feeling about.

GB: I certainly did not expect the girl to be the one who was going to be gung-ho about killing Stephanie. There’s some buildup to that, but it’s certainly one of those left turn moments, especially as you’re being confronted with that choice. In some ways, it feels like she acts as the devil on your shoulder to say “no, this is fine, you can do this.”

Darin: I think that’s pretty accurate. We were trying to get that kind of reflection through Becca, and the chapter was more about Becca than it was about Shel. It was a little bit of a mirror of season one, in that respect, but trying to turn its on end and put you in the more immediate situations and still try to show how those things react over time. And still within a 20-minute story.

GB: It’s funny. I didn’t know you could leave in the RV. The Walking Dead series, in general, will sometimes present the false choices of “oh, here’s maybe an option and then you can’t do anything with it.” So I didn’t even examine the keys, I just assumed I cannot leave in the RV, that’s not going to be an option. I just decided to buck up and kill Stephanie.

Ainsworth: Oof!

Group: [laughs]

Ainsworth: You’re ready for this world.

GB: It made me feel like a real asshole when I found out that it was an actual choice.

Group: [laughs]

Darin: That’s why those choices aren’t black and white. Just because you left doesn’t mean that’s necessarily the best thing.

GB: That’s definitely part of the reason why I’ve played the series with the notifications turned off. I’ve always felt, at least for the way I play that game, that makes it too much of a game for me, I guess? If I’m constantly aware of the fact that this person is taking notice of this, then I’m thinking “oh, well, that’s part of a branch,” and I start thinking too much about how that reflects my choices, as opposed to just making a choice in the moment. Not messing with the keys was similar to that.

Ainsworth: I think it’s interesting with the choice notifications. Some people love them, some people don’t like them. They can cause you stress, but I also feel like with them off, just as much stress. It’s something we found by watching people play the game, really interesting to watch them respond kind of the same way whether they have them on or not.

Darin: It’s definitely there to remind you that world is paying attention to you, but there is no right or wrong answers in The Walking Dead universe. They’re not telling you that what you’ve done is better or worse than whatever other choice is presented to you, it’s just letting you know that it’s going to matter one way or the other.

GB: My wife is a big zombie fan, she doesn’t play a lot of games, but she was really interested in checking this one out. So I steer the controls, so she doesn’t have to jump over that hurdle, and then she makes all the choices in the game for me and I’m forced to live with them, even if I completely disagree. This was the one choice in this episode where she just said that she refused, and shoved it off on me.

Group: [laughs]

Darin: That’s good. She weighed the consequences of both actions and all of it seemed shitty. I’ve done my job. [laughs]

Ainsworth: It’s a Walking Dead choice. If everything seems shitty, we’ve done our job. [laughs]

GB: With that choice, you make it and it fades to black. Was there any consideration of explicitly showing more of the consequences?

Darin: There was never really any consideration of showing any further outcome from that decision. You knew the weight of it, and you knew your choice. Just letting you sit with that and not showing one way or the other what happened was always the way we wanted it to end. The important thing was what decision you were going to make, and not what comes out of it.

Ainsworth: That decision isn’t really about Shel, right? It’s about Becca. As far as Becca’s concerned, it’s done after that. That’s the most important part of it. Whether or not you’re going to go shoot Stephanie, Becca is watching you go shoot Stephanie, and that’s what it’s important. It was over from the character’s standpoint.