Card Advantage: The Design of Magic: The Gathering

By gamer_152 0 Comments

When we deconstruct one type of game, we learn something about all types of games, but Magic: The Gathering is a particularly instructive candidate for analysis because it's easy to predict how the abilities of entities in this game will affect other entities. In MTG, when you cast a sorcery on a player or have one creature fight another, you don't have to worry about aiming or positioning as you do in map or grid-based battles, nor do you have to guess how dice rolls will randomise their effects. If a card says "Does 3 damage to target" and your opponent cannot block it, it does 3 damage. That makes Magic a lot simpler to talk about and allows us to deconstruct it as an exercise in strategy. We don't get too caught up in the action, spatial, or dice roll mechanics of most other competitive games.

Because of the certainty you have in the application of your Magic cards, quick fingers can't save you, and at least after you've drawn your cards, you're unlikely to get a reprieve from luck. Threats are immediate and real, meaning that you must take them seriously, and the game can turn on a dime. But we're getting ahead of ourselves. To understand Magic, or any game, we must ask why they give us the tools they do. Why can we pick up the ball in basketball when we can't in football? Why does Puyo Puyo allow us to rotate pieces? Why can we jump in Donkey Kong Country?

Abilities, Restrictions, Obstacles

Many of our abilities are chosen by designers because they let us directly achieve our goals. In basketball, we need to be able to pick up the ball because we must be able to shoot it at a small raised target. In Puyo Puyo, if we can't rotate pieces, we often can't fit them into place to clear them. We can also turn these ideas on their heads and say that the objective flows from our basic tools. Why is the goal in basketball an elevated hoop? Because that matches our ability to pick up and throw the ball. Why is clearing the blobs the objective of Puyo Puyo? Because that's something you could do with the power to drop and rotate coloured pieces.

Games will also include restrictions on our abilities so that we can't complete the goal trivially. Sports inherently have restrictions in that you can't change the laws of physics, and there's a top end to what any human body will be capable of. In the video game space, Puyo Puyo imposes simple rules of bounding, so we can't phase pieces through each other to complete the board. Note that in both cases, it's the restrictions that cause us to stop and think about how to solve problems.

In basketball, you can't throw infinitely far or infinitely accurately, so you must make judgments every time you could shoot about whether you can score the point from your current position. In Puyo Puyo, whatever your ideal placement for your pieces, you must look at what space is available at the top of the pile and determine where the piece you currently control best fits. These principles are pretty straightforward, but they lead us to a more complex realisation about game rules: obstacles in games and many non-fundamental abilities and restrictions are reactions to these base abilities and restrictions. When I say obstacle, I mean anything that keeps us from reaching our goal.[1]

In Donkey Kong Country, we have the ability to walk from the left side of a level to the right, which is logical from the perspective that the goal is always on the rightmost side of a stage. The game responds to that ability by placing obstacles in our way: crocodiles, mice, and other villains stand between us and the end of the level, thwarting our walking ability. The game's jump is then an ability that responds to these obstacles, allowing us to arc over these troublesome critters if used correctly. But so the jump doesn't drain all the challenge out of the game, we get the bee enemies. They're obstacles that move back and forth through the air on fixed paths, potentially preventing us from jumping past them if we're imprecise. For both the walk and the jump, there are boundings and limitations that prevent us, say, just leaping over the whole level or running through walls. These are restrictions.

For an example within the strategy arena, take Advance Wars. In this turn-based strategy title, we have the ability to create Infantry units and move those troops across the field. Infantry can also capture a facility on its current square or attack adjacent units. We can use these powers to reach the win conditions of either capturing the enemy HQ or defeating all units on the field. Restrictions such as limited funds with which to train the Infantry and a maximum movement distance for the units clamp them.

The game responds to the Infantry abilities with a new kind of unit that has a better movement ability (or a less restricted one, depending on how you want to see it) and a high effectiveness against Infantry: Recon. Recon is an obstacle. To counteract the Recon, the game gives you the ability to dispatch Light Tanks, which also have long range and are super effective against Recon. The Medium Tank is then an obstacle with which the game responds to your Light Tanks. Note from the Advance Wars example that if you have a multiplayer game, the abilities of one player appear as obstacles to their opponent, and vice-versa. In Advance Wars, your army is an obstacle, and mine are the products of abilities and have abilities in themselves. But for you, my army is the obstacle, and yours have the abilities.

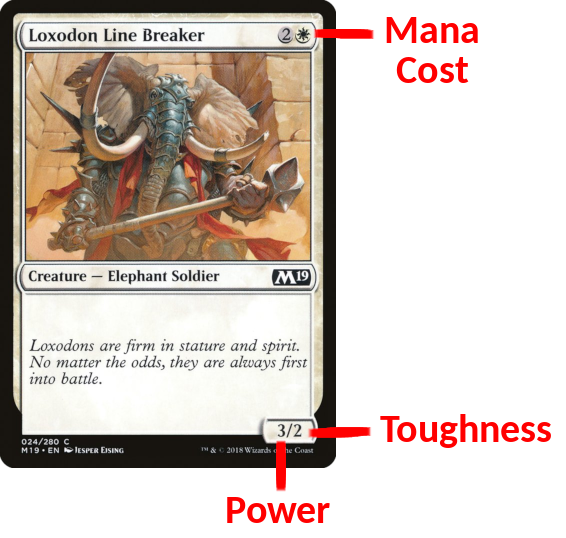

In Magic, every creature card has three important numbers on it: their mana cost, their "power" or attack, and their "toughness" or health. Players also have health values, which, in most formats, start at 20. The goal of each match is to reduce your opponent's health points to 0 before they can do the same to you. Technically, mana cost usually includes a colour or colours in addition to numbers, and sometimes, there are ways to win that don't involve damaging an opponent. However, we can't get too bogged down in details for now. These are the basics. The core attributes of these cards: the power, toughness, and cost, were not chosen from as large a pool of possible mechanics as you might imagine. Instead, they are how each card implements abilities that let us reach our goal, obstacles that prevent us or our opponent from using abilities without restraint, and a restriction on using such abilities.

If our mission is to whittle down our opponent's life points, each creature's ability to do X amount of damage lets us pursue our goal. The role of the ability to block Y amount of damage is also obvious through this lens, as we need to preserve our own health to win. Our creatures and their abilities to cause and block X and Y amounts of damage are obstacles to our opponents, just as their creatures, with their offensive and defensive abilities, are obstacles to us. The mana costs on these cards are then restrictions to keep us from playing a legion of very high-stat abominations out of the gate. Again, restriction leads to constructive play as we must make calculated decisions about what to play, knowing we can't just conjure any creature we'd like to the field. As in other strategy games, the cost associated with playing cards also expands the play so that we're not just toying with military systems but also economic ones. In Magic, players can be rewarded or punished based on how well they cultivate mana.

Attacking and Blocking

MTG can only squeeze the maximum potential from its power, toughness, and cost metrics by having the right rules to make them clash in complex but reliable patterns. In any self-respecting strategy game, the outcomes of our actions must be reasonably predictable. If you can't tell what will happen when you, say, attack an enemy unit or raise your theme park's budget, there's no tactical way to approach these actions, actions which allow you to reach your goals.

Recognise that how Magic implements "toughness" allows us to predict the outcome of battles over time. Other games have a unit's health value stay consistent between turns. Standing out from the crowd, Magic has each creature heal back to full toughness at the end of each turn. This means that when you summon a fighter onto the battlefield, you don't have to speculate about whether a player will be able to chip its health down over a few turns. You know that your Academy Wall with 5 toughness can only be destroyed by a creature with 5 or more power. Likewise, an attacking player knows exactly the capability and limits of your 2-power Deeproot Wayfinder. If players know where they stand, then they also know what they need to do to get ahead.

The game has another trick for making creature selection interesting: it advantages blocking players over attacking players. It does this through a few means:

- As already mentioned, all cards heal up at the end of a combat phase. So, if an attacker doesn't have the power to overcome a blocker's cards, that blocker can defend indefinitely and not take a hit to their player health.

- An attacking player can only choose to attack an opposing player; they can't target a specific enemy creature to lay into. The defending player picks which creatures block which attacks, and they may use any number of creatures to block a single attacking monster.

- Attacking "taps" a card so it cannot block on the next turn, but blocking doesn't tap. In other words, if you attack with a creature on this turn, it can't block an attack on your opponent's next turn.

- Creatures cannot attack until two turns after they are introduced to the battlefield, but they can block immediately after being played.

- It doesn't matter how much power a creature has; a creature of any toughness can block it, even if it dies to protect its controller.

Again, if you're a dyed-in-the-wool Magic player, you'll be jumping up and down to mention the cards that can break these rules, but the systems I described in those bullet points are the default. As a beginner to the game, you might think that two creatures with 2 power and one creature with 4 power are equivalently destructive. You quickly discover this isn't the case. If an opponent had a fighter with 4 toughness on the field and you could pick which creatures your cards attack, you could direct both your 2-power soldiers to hit that 4-toughness card, and simple arithmetic says they'd destroy it. However, because the opponent decides how damage is distributed between their cards, in that scenario, they could block only one of your 2-power creatures with their 4-toughness creature, and your attacker would still be 2 power away from defeating it.

If two 2-power creatures and a 4-power creature are functionally different, then we must engage our brain to play. In our strategising, we must be conscious both of the total power and toughness of our army and how those stats are divided between each warrior. We can make smarter decisions or dumber decisions that will affect the outcome of the play, giving Magic strategic depth and rewarding bright minds.

Note that because even a weak monster can block a strong monster, MTG can veer away from being a game about who has the highest numbers. Generally speaking, each player gets more mana as matches progress, allowing them to play more damaging cards with higher mana costs. In other games, implements with low attack and defence may be discarded as higher stat ones become available, but in Magic, low-end cards can have a part to play, too. Because preventing all damage means assigning one blocker for each attacker, both players must also consider the quantity of creatures on the field as well as the quality. If you have more attackers than they have defenders, it doesn't matter how powerful their blockers are; some of your strikes are going to fly through. Shifting to the other side of the table, we can see that if your goal is to stop damage, it doesn't matter what power or toughness your blockers are; you just need as many as there are attackers.

Because squishier creatures can still be useful, even as more powerful fighters become available, the number of potential tools you can use only increases as play progresses. With a broad array of tools at your fingertips, you have a wide gamut of strategic decisions open well into the game. Players are asked how they want to balance between quantity of creatures and strength of creatures. The game also queries combatants on how they might stop their opponents from reaching their desired balance of quantity and strength. This is players working within restrictions to develop abilities and place obstacles. Note that because a creature attacking taps it, players are discouraged from attacking on every turn, going into autopilot. Even letting yourself take damage can be the fitting move because the game is played across multiple turns, and cards have both defensive and offensive power. So, to sacrifice a creature to block an attack or to tap a creature to make an attack is not just a choice about preventing or causing injury. It's also a statement about which offensive and defensive abilities you want to have access to on future turns. Again, choices must be measured and relevant to the specific game state if you want to win.

In Magic, we find not just that games should include abilities, obstacles, and restrictions, but also what kinds of abilities, obstacles, and restrictions are interesting. Each ability, obstacle, and restriction should be able to affect others in a multitude of ways. Each of those effects should be significant enough to change how the player makes decisions.

What It Takes to Develop the Rules

Of course, while these three numbers (the power, toughness, and mana cost) can generate countless different topologies in the play, if they were all the gameplay attributes of a creature, Magic would be bland. Creatures would be mechanically identical and not vividly characterised. And when combat is just crunching a list of numbers, most audiences tend to feel it's just boring accountancy. So, Magic has cards that are not creatures but act on them: artifacts, enchantments, sorceries, and instants. But without expanding our conception of what attributes a card can have, all these spells can do is increase or decrease power, toughness, or mana cost, or remove the attacking or blocking ability. Else, they act directly on players, but players don't have many attributes beyond their health. There's no getting out of it: we need more stuff.

As Into the Breach revealed to us, strategy games are effectively series of puzzles strung together. They are daisy chains of logic problems in which we must work out the correct actions and the right order in which to take those actions so that we might hop a logical fence. For Magic to make more puzzles, it needs more pieces. I think a newbie designer would be inclined to fill out the game by adding additional stats to each unit. If a few numbers means some depth, it follows that several numbers would mean enormous depth. Long stat sheets are often the solution when we want a mechanically sizeable vehicle in a racing game or player character in an RPG. Yet, these walls of figures work in RPGs and racers because we control one car or often one person at a time in these genres, and we don't typically have to constantly reassess most of those numbers. Magic is different in a few ways:

- We can have platoons of soldiers on the field at once. If you control a single avatar in a game, it being a pack mule for abilities and stats isn't overwhelming. Even if you command four party members in an RPG, with the right concessions, it's manageable. If you control a lot of creatures and every one is a mechanics homunculus, that stops being true.

- Cards must show any figures on their face because, outside of a video game, you can't hide stats away in a menu. Even in a simulation racing game, you don't have every fine detail of your vehicle thrust in your face. That means you can race without the screen becoming a swamp of statistics, but as Magic is a card game, it has to put everything up in your grill. If there is a lot of text on each card, that could make you pop a nerve, and designers risk having more text than they do space to print it.

- We must constantly assess the figures on our cards as they relate to other cards. We'll cover this more in coming sections, but the stats and abilities of your cards have a different effect on the overall game state based on what other cards are on the field. This means that you always have to be conscious of the stats and abilities of each card, so you need to rescan the play space regularly, and if you can't do that quickly, you're undertaking these exhausting reading exercises multiple times per turn. Even opening a booster pack could turn into an afternoon of research, and a glut of information on each card would make the game inhospitable for newcomers.

It's a natural impulse to want to be maximalist in your design and cram in all the cool features you can think of. But effective design is often about pairing your creations back to only the parts they absolutely need. And "different" in game design is often better than "more". "More" similar abilities and restrictions to the ones you already have make your game harder for the player to learn and parse moment-to-moment. They also do not increase the play's variation or give the player more distinct options to choose from. When an element is individual, it is memorable and can provide a different choice from what's already available.

A note on stats before we go any further: We're going to be looking at stats and abilities, but as we do, it's important to understand stats as a component of abilities. That is, we could view being able to attack as an ability and a creature's power as being something separate, but I'm viewing the ability to cause 4 damage to a target as an ability: a singular concept. One reason vehicles and characters in games often end up so decorated with stats is that their stats and mechanics are reliant on the existence of other stats and mechanics internal to them. Or, seen in reverse, their stats and powers are designed for application through new abilities. Their core powers either do not make sense without these new abilities (they are one half of an idea), or they feel thin if they're not expanded on by other mechanics. I realise that explanation is a little heady, but the pattern is clear in games with talent trees.

For example, the Necromancer in Diablo IV can learn an ability called Blood Surge, which damages multiple enemies. If the player character knows Blood Surge, they can then learn Enhanced Blood Surge, which allows them to heal when they damage enemies with Blood Surge. On the talent tree, Enhanced Blood Surge can then branch to Paranormal Blood Surge. Paranormal Blood Surge allows Necromancers to charge up a bonus damage ability if they hurt creatures with Blood Surge while they have 80% or more health. So, there's a system here that is made to pile abilities onto a character like plates onto a busy waiter. You can't have Paranormal Blood Surge without having Enhanced Blood Surge. You can't have Enhanced Blood Surge without having the basic Blood Surge, and even knowing Blood Surge is reliant on serving the Necromancer class.

And if this specific path to Paranormal Blood Surge wasn't enforced by the game's rules, the player would still be encouraged to take something like it because it's maximising the utility of the powers they have. You can only activate Paranormal Blood Surge's bonus if you are at 80% or higher health, and you are more likely to be at 80% or higher health if you use a life-drain spell that can hit a plurality of enemies, a spell like Enhanced Blood Surge. However, it's also not a coincidence that this Blood Surge ganglia exists on a talent tree. Developers design upgrade paths with the idea that they help coax players towards acquiring abilities that work well together and prevent them from easily branching into diverse powers that might not stack well or might give their character too broad a range of strengths. You don't want one hero who is effectively a Barbarian, Rogue, and Necromancer.

If the Diablo example doesn't float your boat, imagine if your MTG creatures had all the base stats of a Dungeons & Dragons character: STR, INT, DEX, CON, WIS, and LUK. The designer would have to come up with powers or sub-stats that all of those stats could feed into. E.g. Having STR increase carrying capacity or INT determine the number of starting languages a creature knows. Or there are the many games that give the entities we control equipment or upgrade slots, like Shining Force or The Crew. Those slots call for lines of items or powers we can insert into each. So, simply trying to deepen our MTG orc by giving it six base stats or space for a new set of brake pads is likely to overcomplicate the play. The abilities of other games are often designed to exist within large mechanical webs, which, for the reasons mentioned in the earlier bullet points, are beyond the scope of one Magic creature.

You'll also notice that when we make the possession of an ability dependent on the ownership of a previous ability, we group the same abilities together, reducing the variation of the characters and objects we control. Again, Paranormal Blood Surge doesn't come without Enhanced Blood Surge, and abilities related to CHA are going to cluster together on high-CHA characters. In most games, that clumping is not a problem because there are so many abilities we could pick for one character to wield that diversity is possible anyway. But to reiterate, we can't jam a lot of abilities on one Magic card, meaning if abilities cluster together, you're going to end up with a lot of similar cards.

The upshot is that, for diverse and streamlined play, Magic needs abilities that could be applied to any number of creatures. I'm talking about abilities that are only dependent on the simple underlying stats of mana cost, power, toughness, and the fundamental mechanics of summoning, attacking, and blocking. To reorient this idea, if cards have few base attributes and mechanics, they are mostly blank slates for all sorts of combinations of abilities to be applied to them, assuming those abilities applied to them are not dependent on the existence of others we could apply to them.

As each turn in Magic is a puzzle, I'll also refer back to my brief introduction to puzzle design, in which I say these many possible interactions between parts create diversity, challenge, and mystery and ask for ingenuity from the player. If there are many different ways in which elements could be made to interface with each other, the player has a lot of options in finding the best or correct one, and must work hard to do so. There is a big haystack in which to find the needles. Widely applicable abilities also create flexibility. The fewer stats on any entity in a game, the less specific it is in its nature, so the less specific it can be in its function. If it's less specific in its function, then, by definition, it's highly adaptable to many different situations.

How Magic Develops Itself

Magic's creature card template achieves the dream of being open for many different abilities to be painted on. And the abilities it embeds on those templates reach that goal of being non-reliant on others. Together, these design elements allow for cards that are easy to parse, diverse, flexible, and can be combined in many different permutations. Let's look at a few common Magic card abilities to which these criteria apply:

- Deathtouch: This creature destroys any creature it blocks or that blocks it, regardless of the creatures' relative power and toughness values.

- Lifelink: When this creature deals damage, the player that controls it gains health points equal to the amount of damage it dealt.

- Flying: This creature can attack the opponent without being blocked.

Note that the use of a name for each of these effects allows the creators to compress the rules. If a card said something like, "Any damage this creature does to a target is returned to the player as life points. In addition, it can attack opposing creatures without being blocked", that's an eyeful for the player. If, however, the card says "Lifelink, Flying" on it, the player can efficiently process its role and move onto the next. MTG: Arena, a video game counterpart to the card game, has a very neat layout of this data. Cards are stamped with the named abilities they carry and any rules that apply exclusively to them. The player may also hover their cursor over a card to see a popup explaining those abilities in full. The newbie player can glean all the information they need about a card without that text getting in the knowledgeable player's way. They each know where to look. Note that sprites, models, or UI icons are also shortcuts games use to signal complex abilities and restrictions through simple symbols.

Magic favours blocking creatures, and players generally only increase their mana cap by 1 each turn, so without unique abilities and non-creature spells in play, stalemates would be the norm. Each competitor looks out on a wall of their opponent's creatures, blocking them from afflicting damage. Magic becomes mostly a game of working out how to avoid or break those deadlocks through these more colourful abilities. You can have angels fly over enemy units, Lifelink keep you healthy long enough to play devastating endgame monsters, or Deathtouch destroy a living fortress. Non-creature spells also help resolve these stalemates: Lightning Strike can damage an enemy beyond their minimum health, Stasis Field can bind their ability to attack, etc.

Our opponent then uses the abilities of their creatures and non-creatures to overcome these obstacles and create obstacles for us. Abilities are designed with this countering principle in mind. Opponents can intercept our flying creatures with beasts that have Reach, they can use Negate to cancel our Lightning Strike, they can destroy our Stasis Field with Citizen's Crowbar, etc. We may then head off or overcome those impasses, sending up more powerful flying creatures, Negating their Negate, or exiling that Crowbar. And matches consist of these bouncing counters as, with each back and forth, one player tries to amass more power than the other.

Whereas other card games often lock you into operating within a ruleset, in Magic, you can rewrite the rules in your favour. Think one of your creatures should have Flying that doesn't? Think your opponent should lose 1 life every time they draw a card? Think they shouldn't be able to target one of your creatures with a spell? All these rules can be written into the book. But don't get cocky because your opponent will be trying to cross out your rules and scribble in their own.

Often, matches resolve by one player being able to cast plenty of beneficial cards while preventing their opponent from doing the same, such that the winning player can reinvest their power to get more power. Think of it like a stock buyback but with merfolk or the colour red. Players might boost the power of their creatures, letting them easily mop up enemy fighters, which only increases the gap in brawn between one player and the other. They might stun opposing creatures, giving them time to draw more cards and increase their available options.

Note that a health points system with a relatively low number of starting points means that if either player does not properly defend themselves, the other can quickly eliminate them. A small store of HP can be a more expedient means of resolving a game than counting up to a distant target number. If you end up in an imbalanced deathmatch in a shooter, all you can do is keep dying until your opponent reaches X kills, which could take a while. If you're in a one-sided hockey game, you just have to keep playing for the full 60 minutes. In Magic, it's not always pleasant to be on the receiving end of accumulating power, but when you are, you lose quickly and can move on to the next game without any wasted time.

Synergies

Building and playing a deck effectively frequently involves exploiting synergies between the cards. That is, being conscious of how abilities, restrictions, and obstacles relate to each other and might be matched for the best results. Let's look at an example turn: I use my limited mana to summon Hallowed Priest, a weak creature that gets extra power and toughness when I gain life. I also unleash Electrostatic Infantry, a slightly stronger creature that gets more power and toughness when I cast a sorcery or instant spell. So, I have two pretty wimpy creatures down and haven't taken advantage of their unique effects. That's not exactly fearsome.

Now, imagine I play Impassionated Orator, a low-level creature that gives me 1 life whenever I play another creature, and Hallowed Priest. When I play Hallowed Priest, that will trigger Impassioned Orator's effect, which will give me 1 life, and when I get that 1 life, that will trigger Hallowed Priest's effect, which increases its stats. Or I could play Electrostatic Infantry and then Abrade. Abrade is an instant spell which does 3 damage to a creature. I could destroy an enemy and, at the same time, have Abrade trigger Electrostatic Infantry's effect, buffing it.

Where, in the first example, we got two creatures down in their feeblest forms. In the second example, we got one creature in the trenches in a so-so state, but managed to upgrade the other, and gained a point of life. In the third example, I managed to play and power up a creature on the same turn and destroy an enemy creature. That's the power of harmonics between abilities. It's the rough equivalent of having a character in The Sims use a chair and TV at the same time to increase their fun and comfort or using your jump and attack simultaneously in Duck Game for an aerial attack. Note that Magic's play is nuanced enough that it doesn't just matter what cards we throw down but in what order. If we don't have Electrostatic Infantry on the battlefield when we play Abrade, then we won't trigger its boost ability. If we play Hallowed Priest before Impassioned Orator, then we won't trigger either of their abilities.

We must also consider how our entities will interface with our opponent's. That consideration is by no means unique to Magic; it's how any strategy game works. Still, a great strategy game can create many different dynamics between abilities and obstacles, each with significant and varied implications, which is what Magic does. If your opponent has played Call in a Professional, which prevents you from gaining life this turn, you'll want to shy away from the Impassioned Orator/Hallowed Priest Strategy, if at all possible. If your opponent has summoned Electrostatic Infantry, that's an indicator they'll be looking to power it up in subsequent turns. You could hold back some mana and a Counterspell card to prevent them both being able to activate the effect of a card like Abrade and stop them boosting Electrostatic Infantry in one fell swoop.

If your opponent is using cards that insta-kill individual creatures like Annihilating Glare or Bone Splinters, you might want to refrain from casting a few high-power creatures and go for many low-power ones. They can't take them all out. If they are using many low-power creatures to block yours, maybe try one with Trample like Titan of Industry or Glacial Crasher. It will deal damage to any creature blocking it, and then any damage in excess of the total toughness of the blocking creatures to your opponent.

Dynamics don't just exist between cards but also within them because a lot of them have this IF/THEN construction to their abilities. We saw this with Electrostatic Infantry, where IF we cast an instant or sorcery spell, THEN it gets more power and toughness. I'd also point to cards like Mystic Skyfish, that says IF you draw your second card in a turn, THEN it temporarily gains Flying. Or there's Angel of Vitality, that says that IF you gain life, THEN it will give you 1 extra life on top of it. The "IF"s cause their abilities to only trigger within certain contexts, meaning that players must both consider whether an entity's abilities are appropriate to the current context and whether they can use other abilities to create a context in which those abilities would achieve success. Or, in the case of the opponent's cards, a context in which those abilities would fail. One reason that Magic can support so many expansions is down to the interchangeability of the IF rules and the THEN rules. You can pair different IFs with many different THENs and many different THENs with many different IFs.

Strategies

A constituent of strategy games with these many synergies between abilities and obstacles is that within each strategic approach, you can find sub-strategies and sub-sub-strategies, branching downwards. A tall tactical tree gives the player plenty to learn and explore. In MTG, one macro-level strategy is to pool mana faster than your opponent to let you get more or stronger cards out sooner. But how are you going to get that mana? Creatures that let you tap them in exchange for mana? Spells that allow you to play more than one land card each turn? Cards that let you reuse the same land to produce more than one mana? Treasure tokens that you can sacrifice for one more mana for that turn? You'd likely prime your deck for a combination of these sub-strategies, but which do you use, and how much do you bend your tactics towards each one? That's a decision you'll have to make both when deck building and on a per-hand basis because, during a match, you won't have access to every card in the deck. You'll only have access to the contents of your hand.

If we go down the road of recruiting creatures that can supply mana, which creatures do we pick? How about Ilysian Caryatid, a 1/1 (that's 1 power, 1 toughness) plant that gives up 1 mana unless we have a creature with 4 or more power on the field, in which case it gives up 2? How about Citanul Stalwart, which produces mana if you disable one of your artifacts or creatures until the next turn, but comes in at half the cost? Or there's Llanowar Loamspeaker, a 1/3 druid who can add mana or temporarily turn one of your land cards into a 3/3 monster.

Each of these creatures, or more to the point, their abilities, offers advantages and disadvantages, meaning that you have different choices in the play here, and you're not just picking the same choice reskinned. You might be better off putting down the Caryatid if defence is not a priority, but high mana gain in the long term is. Citanul Stalwart is faster to get out than Caryatid, but is not as high yield as Caryatid in the mid and late game. Llanowar Loamspeaker is not as fast as Stalwart, nor can he even give up 2 mana like the Caryatid, but he offers a lot of offensive and defensive power for a creature you can play early. As a bonus, he allows you to switch from a mana-gathering strategy to a more aggressive posture quickly. Some Magic cards are valuable not just because of their precision at one task but because they allow you to multi-task.

Or maybe you don't want to go down the mana-maxxing route at all. You'd favour a deck that destroys creatures on the field regardless of their stats. If that's your style, you've got terrors like Bilious Skulldweller or Battlefly Swarm that are charmed with Deathtouch. You have instant spells like Infernal Grasp or Hero's Downfall that can take out an enemy at any time, as long as you have the mana. There are nightmares like Sheoldred or Gravelighter that demand the opponent sacrifices a card when they enter the field.

But again, none of these is the strictly correct choice because none of their abilities overcomes all obstacles and restrictions. Unlike the creatures we discussed, Infernal Grasp and Hero's Downfall let you pick which minion gets destroyed, and you can cast them even on an opponent's turn. Yet, contrary to the creatures, once instant spells are used, they're used, whereas creatures are persistent. Creatures also come with the advantage that they can damage and block the opposing player. But the creatures I've named are also non-fungible.

Skulldweller is so cheap you can play it on the first turn of a game. You can do the same with Battlefly Swarm, plus it can fly, but unlike with Skulldweller, you need to pay 1 mana on any turn you want to activate its Deathtouch. Gravelighter can also fly and is stronger than either of those animals, but not only is it a bit more expensive, if you activate its power to make an opponent sacrifice a creature, it forces you to cull one of yours too. Sheoldred is the strongest and most expensive of these creatures, and you can sacrifice her to unleash a flooring barrage of spells over the next few turns. But Skulldweller and Swarm kill creatures by blocking them, whereas Sheoldred and Gravelighter just ask an opponent to pick a fighter to mulch. Sheoldred and Gravelighter are the least precise in who they target.

And again, in deploying these strategies, we must consider the cards (the obstacles) the opponent is rolling with. If your opponent starts playing fast-acting high-power creatures, you might not want to play weak mana-yielding creatures and instead switch to soldiers with higher defence before your foe zeroes out your health. But if your opponent can't do any significant damage to you right now, low-cost, weak mana crops are highly practical.

If your opponent is playing a lot of modestly-powered tokens, creatures with Deathtouch aren't much use because they'll only kill one attacker among many, maybe dying in the process. You might want to fight quantity with quantity. If you have creatures you can't afford to expend in a skirmish, using instant spells to kill enemies is an excellent strategy, but won't work on monsters that have Hexproof. Gravelighter is at an advantage if none of the opposing creatures have Flying or Reach, but at less of an advantage if they do. That is, unless you can kill off those creatures. And Sheoldred's brilliant if your opponent lacks strong cards, but it's not impossible to overpower her.

Conclusion(s?)

To look back over the key points of this article, designers carve play through abilities, restrictions on those abilities, and obstacles, all of which they create relative to goals, and other abilities, obstacles, and restrictions. We can also take from Magic that it's not just necessary to have abilities, restrictions, and obstacles in a game, but that each ability of significant power must be met with restrictions or obstacles that specifically address it. And where entities have abilities, those specific entities must have the right restrictions applied to them and obstacles complimenting them. Magic provides a teachable example in that, in its play, not only do general principles of mana cost or blocking exist, but each creature that can be attacked must be blocked to prevent them from inflicting damage, and each creature that could be played is bounded by a cost. This is specificity in ability and restrictions. To abandon these rules for any one card would be to create an imbalanced entity.

If a game is intelligently designed, its restrictions, abilities, obstacles, and goals can relate to each other in many significantly different configurations. With enough different synergies between the entities in play, we must consider our actions based on context. Many different strategies become possible, creating variation and challenge, and allowing us to come up with inventive solutions to problems. Designers can create a galaxy of synergies between these elements by giving play entities just a few inherent characteristics and designing abilities that are not dependent on many others. For a game with a lot of controllable entities or where entities must feature all elements on their face, this is essential for making the game parseable.

But here's where I have to burst the bubble. In these examples, the Magic I've described is the game when it runs ideally, and in many matches, it's not that game. It becomes argumentative and dysfunctional, waging war on its own best features. At least half of the Magic: The Gathering games I play, I find irritating or demoralising, some to an extreme. In the future, I'll publish some blogs on the self-defeating aspects of Magic's design. But despite those objectionable matches and moments in which it squanders its potential, I keep playing Magic because when it goes right, Magic offers not just a tree of possibilities but a grove. Thanks for reading.

Notes

- You could also consider restrictions to be built into abilities or restrictions and obstacles to be a singular category. I don't think there's one correct framework through which to view these components of games, but I believe the one I've laid out here is helpful for understanding them.