Long Dark Winter: The Division and US Policing

By gamer_152 10 Comments

Note: The following article contains major spoilers for The Division, discussion of explicit racism, and graphic descriptions of police brutality.

Maiming and killing are no trivial acts, which makes it impressive that so many video games convince us that we should pick up a weapon and turn its business end towards its characters. But then, a lot of them relax us into it by distancing their fictional violence from real-world violence. We shoot robots or demons, the gore is cartoonified, we battle in the distant past or a hypothetical future, or play someone morally compromised. The politics get thornier when developers argue that modern-day mass violence is an instrument of justice. Series like Call of Duty and Splinter Cell have had to fabricate elaborate fantasies involving divergent histories and storied conspiracy theories to make that case. That precedent makes it unusual that Tom Clancy's The Division provides gossamer-thin rationalisations for our massacres. Released in 2016, The Division is a Ubisoft shooter about a clandestine and unregulated army that saves New York City by deploying lethal force against American citizens.

The Division's prologue flashes us unsaturated images of Black Friday on the East Coast: the peak of the consumer rush. Unbeknownst to the hungry shoppers, they are spreading a deadly smallpox strain. Subsequent to this, rioting begins in New York City and policing fails to extinguish it. Society in the metropolis grinds to a halt: public services atrophy, residents evacuate from their homes, and the city's arteries clog with abandoned cars and uncollected rubbish. To remedy the crisis, the government activates "The Division", a sleeper cell of special agents hidden among the American populace. We play as one of its intrepid soldiers.

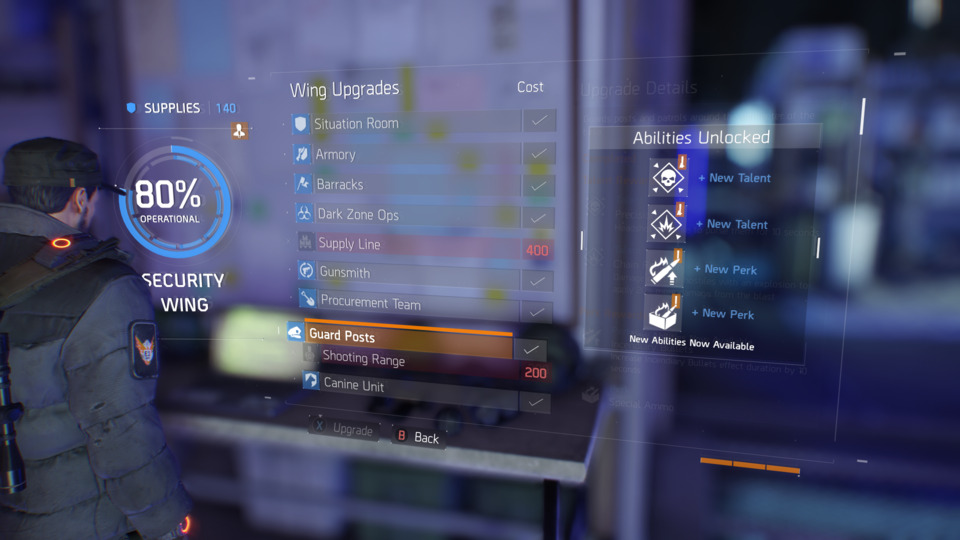

Our first mission of significance is evicting armed belligerents from an NYPD nerve centre. It's not clear what the value of the police base is. Still, given that our vague heading is the rehabilitation of New York, our early reclamation of this building suggests that it's a priority to resurrect the NYPD. That's a disconcerting idea because the big apple's law enforcement has a rotten reputation. Among the highlights are over 200,000 extralegal stop and searches, $250 million paid in compensation for police brutality from late 2015-early 2020, an interminable pattern of murders, and a consistent record for violently attacking peaceful protestors, including LGBT and black rights activists.

Advocacy for abusive and unaccountable state organisations runs right through the heart of The Division. The titular agency is a paramilitary that can enact any violence on other human beings with legal impunity while still benefiting from a framing as "the good guy". Over the next 6,000 or so words, we're going to look at how The Division presents non-democratic and militarised domestic law enforcement. We're also going to review the history of discriminatory ideology and practices the game plays into.

To reclaim New York City, the developers have us attack four factions: the Rioters, the Cleaners, the Rikers, and the Last Man Batallion. The Rioters are what they sound like. The Cleaners are a conglomerate of former sanitation and custodial workers; they burn out the virus wherever they find it, even if that's inside another human being. The Rikers are a gang of escaped inmates from Riker's Island. And the LMB are a private military company that we'll put to one side; they're the odd one out of the four.

All of these aggressors attack on sight, fight to the death, and are prone to wanton acts of cruelty. You can see them beating dead bodies in the streets, holding innocents at gunpoint, and running at us with bats, screaming. In one phone call between them, a man explains to another how you can kill a child's dog to intimidate the kid and then eat it for food. In another, a delinquent confronts the possibility that he may kill a minor. There's an audio diary that follows the transformation of a run-of-the-mill New Yorker into a rioter. It listens like one of those gothic novels where someone slowly realises they're turning into a vampire. He's an average joe when he starts, but seven entries in, he's kicking a pensioner in the stomach for their briefcase.

From rioter to cleaner to prisoner, none of The Division's subjects gets a fair-handed portrayal. Instead, the game casts morally complex and even innocent community members as bloodthirsty cutthroats because that's the only thing that could justify the merciless and crushing military might we exert against them. The violence in any video game is a fair target for criticism. However, this RPG is worthy of particular scrutiny because an unaccountable enforcement class shooting Americans to death is not a hypothetical. It's happening every month, and the continued snuffing out of US citizens is predicated on a series of shaky and paranoid arguments that The Division regurgitates.

To explain what's so malicious about the game's dynamic between criminal and soldier, we don't need to look any further than the first faction we meet: the Rioters. There are scientific reasons to believe that Ubisoft's future in which utilities and commerce are interrupted would not also be one in which all your neighbours begin foaming at the mouth and reaching for their pistols. Papers from the University of Delaware and the CDC explain that in the immediate aftermath of disasters, looting, violence, and other anti-social behaviour is rare. On the contrary, it's standard that community members rally to keep each other safe, and when people do loot, it's uncommon they steal anything of considerable value. Of course, there have been periods in which America has endured widespread and fiery rioting without any such collapse. Still, we should tread carefully when criticising civil unrest because this concept of the crazed rioter destroying American cities has decades of racial baggage.

Some riots happen in celebration of or frustration with sports results, but the riots that really earn the ire of the public are those with progressive political overtones. A partial exception to this rule was the far-right storming of the capitol earlier this year, but this is an extreme outlier, and some news outlets originally refrained from labelling the rioters as such. There has been little accountability for the actions of January 6th, and the police showed a double standard between how they treated fascist intruders and black rights campaigners.

When progressive demonstrators cause property damage, it's common to hear onlookers saying something like, "I believe in peaceful protest, but can't support rioting. Why can't the rioters be more like the pacificist Martin Luther King?". But the enemies of civil rights have always dismissed peaceful people, movements, and organisations through associating them with breakage, theft, and assault. King was not spared this treatment.

You may wonder how anyone could associate King with criminality; it is impossible to imagine the reverend with a Molotov in his hand. Yet, Alabama clergymen denounced him as inciting "hatred and violence", and the head of the FBI's domestic intelligence division dubbed him "the most dangerous Negro of the future in this Nation". In preparation for the peaceful March on Washington, where King made his historic "I have a dream" speech, officers took up posts on every street corner of the downtown business district, 15,000 special forces operatives stood by, and five military bases coordinated. They were all ready to defend the city against a riot that never came.

Politicians of the time seized on the fear of race riots to win votes. They were a particular focus of George Wallace, who ran four campaigns across the 1960s and '70s. Wallace was a staunch segregationist, and King called him "perhaps the most dangerous racist in America today". Barry Goldwater, an Arizonan senator who ran for President in 1964, provides another high-profile example. He opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act and was endorsed by several members of the KKK. Goldwater's campaign materials railed against black rioting, among other forms of supposed moral decay. According to the New York Times, he would frequently mention these crimes in the same breath as black rights activism.

Richard Nixon, whose successful campaign for President took place in the late 60s, used fear of civil unrest as a proxy to attack non-white citizens. A campaign advert for Nixon emphasised the dangers of urban rioting. Nixon said that the commercial "hits it right on the nose" and was "all about law and order and the damn Negro-Puerto Rican groups out there".

Today, Black Lives Matter, the torchbearer for civil rights, is often caricatured as an inherently violent movement. Right-wing media, Donald Trump, and the Republican Party are standing behind a narrative that began circulating as a kneejerk to a new wave of BLM protests. The narrative is that dangerous, anarchist (read: violent for the sake of violent) mobs are burning down cities and pose a threat to the average American. Even liberal media became preoccupied with the spectre of BLM rioting. Yet, a September 2020 study from ACLED and Princeton University proved that 93% of BLM protests don't involve violence or property damage.

The Murdoch press and the Trump extended universe hold a flashlight under their faces and tell a bone-rattling story about US cities descending into riotous abandon, but according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics and FBI, violent crime rates have been on a sharp decline for decades. In some cases, mainstream media's claims of BLM's misdeeds are outright lies. For example, the New York Post's false story of rioters looting $2.4 million in Rolexes. Or Fox News mislabelling and Photoshopping images of riots and protestors.

Racists exaggerate the degree of rioting and then associate that imagined chaos with black rights movements to dissuade support of them. The picture of black people they paint plays on one of the oldest and most hateful African-American stereotypes: It's the idea that African-Americans are naturally prone to brutish and destructive behaviour. Trump has consistently smeared black rights protestors as "thugs". Nixon and Reagan both launched fiery-tongued volleys at "thugs". Obama and his spokesman angrily referred to participants in the Ferguson, Missouri protests as "thugs", and various right-wing enemies of Obama described him as a "thug". Trimiko Melancon, an Associate Professor of English and Africana Studies at Rhodes College, says:

"'Thug' is a coded and racialized term that people use instead of Black or brown. [...] This is not innocuous and it's not by accident. It's deliberate and strategic and used to undermine the very movement for racial justice and civil rights by creating a particular narrative of resistance, disturbance and even criminality".

Other political entities have forgone the code and resorted to bald-faced racism to stoke anxiety over out-of-control blacks. Nixon said black people "live like a bunch of dogs". In the heydey of civil rights demonstrations, US Attorney General Robert Kennedy complained:

"Negroes are now just antagonistic and mad and they're going to be mad at everything. You can't talk to them [...] My friends all say [even] the Negro maids and servants are getting antagonistic".

The Sergeants Benevolent Association is the union that represents the NYPD's 11,000 police sergeants. In 2019, its President, Ed Mullins, sent its members a video calling black people "animals" and saying:

"The projects will always be dens of crime and violence. Cops will continue to wade into that fray and blacks will continue to attack and ambush us forever. [...] Section 8 scam artists and welfare queens have mastered the art of gaming the taxpayer".

Of the video, Mullins told his sergeants:

"Pay close attention to every word. You will hear what goes through the mind of real policemen every single day on the job. This is the best video I've ever seen telling the public the absolute truth".

Spokespeople in places of power have long derided pro-black movements and leaders, or even denigrated entire races, by associating them with rioting and violence. So far, we have discussed this as a bigoted generalisation. However, we must also understand that in the genuine instances of non-white protestors rioting, they're doing it within the context of societies threatening their autonomy and lives. Again, we can turn back to King who, in a 1967 speech at Stanford University, said:

"A riot is the language of the unheard. And what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear that the plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years. It has failed to hear that the promises of freedom and justice have not been met. And it has failed to hear that large segments of white society are more concerned about tranquility and the status quo than about justice, equality, and humanity [...] Social justice and progress are the absolute guarantors of riot prevention".

King gave some version of his "Other America" speech throughout '67 and '68. A probing 1968 report commissioned by the Johnson administration concurred with him, telling the government that the race riots had been a protest of racial inequality and a product of African-Americans' economic disenfranchisement. In 2020, African-American journalist Zak Cheney-Rice wrote the following sympathetic passage on civil unrest:

"It's hard to imagine, without experiencing it, what your personal breaking point is — the point at which the compounding oppressions and indignities expand your understanding of acceptable recourse. Most Americans will never be driven to this point, but those who are look upon a vista of possibilities, that at least bear some hope of changing conditions. Some of these are illegal. Some are destructive. Rarely do they risk matching the depravity to which they are responding".

To outline that depravity, in both 2015 and 2016, US law enforcement killed roughly 1,100 people. In 2015, the number of unarmed black victims was double the number of unarmed white victims. Police further retain the right to seize money or property from citizens to keep or sell without arresting them or seeing them convicted of a crime.

I am not telling you to go out and commit crimes in the name of rebelling against police. However, if you're looking down from the pulpit of privilege, you might want to think twice before judging people lashing out against this systemic strain. Like it or not, rioting has always been a means for social justice movements to affect change when decades of peaceful outcry have not stemmed the cruelty against them. UK suffragettes damaged property to get some portion of women the vote. Early US labour laws were written in the blood of industrial workers who went to war with their employers. A turning point for LGBT rights was the Stonewall riots which came on the back of chronic NYPD abuse of LGBT people.

The sentiment that you are supportive of civil rights causes but opposed to rioting offers a veneer of socially-acceptable progressivism. In the cold light of day, it makes little sense because the history of civil rights is, in part, a history of civil unrest. Reflexively, we return to the idea that justice is when bad things happen to criminals. However, we need to take a step back and consider who we label criminals, who we trust to stop them, and what we deem appropriate retaliation.

Racist framing of rioters might seem like an issue non-applicable to The Division as the game depicts a racially diverse range of people smashing windows and traumatising civilians. However, the rioter boogieman is a bridge that some politicians erect to cross to problematic crime-prevention solutions. Solutions that make most people worse off, regardless of race, but which have an in-built bias against non-white people. So, whether or not The Division is saying black people cause rioting, it's making arguments about riots used to justify the funding and deregulation of forces that disproportionately hurt black people. And The Division is in love with that kind of low-oversight, high-body count militance in the name of law and order. Again, a little history is needed to understand the problem.

Long before there were organised police in the US, there was vigilante justice, and part of vigilante justice was lynching. Hate mobs like the KKK often claimed to be bringing criminals to justice, even though we now recognise their murders as hate crimes. In the 1870s, the federal government dropped the boot on the KKK, but this isn't the last we'll hear of them.

Other colonial law enforcers were freelance security professionals who protected merchants' goods. In the south, the economy was rooted in slavery, and therefore, many of the original American police were slave catchers. Technically, they were enforcing the law. And when it came to the violent struggles over labour rights, it was the police, both public and private, as well as US troops who stood against the protestors.

In the 1910s, William Joseph Simmons gathered up the broken boards of the old KKK and took to nailing them back together. He distributed a pamphlet to recruit new Klansmen in which he claimed the original Klan "protected property, protected life, and brought order out of chaos". The Klan's constitution, published in 1922, presented them as an organisation for "the lovers of Law and Order, Peace and Justice".

During the 1920s, KKK membership peaked north of 4 million, and they made it a point of pride that under their white robes could be found boys in blue. According to Columbia University history professor Kenneth T. Jackson, about a tenth of the public officials and police in California's cities were part of the KKK. The LAPD chief and the Los Angeles County Sheriff were also members, and the Klan effectively controlled the governments of Colorado and Indiana. Alana Semuels in The Atlantic gives us (content warning for link: hate speech) more:

"Democrat Walter M. Pierce was elected to the governorship of the state [of Oregon] in 1922 with the vocal support of the Klan, and photos in the local paper show the Portland chief of police, sheriff, district attorney, US attorney, and mayor posing with Klansmen, accompanied by an article saying the men were taking advice from the Klan".

The mayor of Portland, Maine, was also a Klan candidate. Until at least the 1970s, there were textbooks in some US schools that described the KKK not as a hate mob but as a collective reinstating "law and order" in the states. There is a historical crossover between US police and violent enforcers of racism. There is also precedent for the hunting of citizens, especially black people, to be whitewashed as upholding "law and order".

So, you can see the implications of a segregationist like George Wallace responding to riots with promises of "law and order" policing; an escalation in the sheer police force deployed against US citizens. Against a backdrop of widespread police brutality and black protest, Wallace fumed that he'd order police to "knock somebody in the head". He pledged he would "call out 30,000 troops and equip them with two-foot-long bayonets and station them every few feet apart".

Nixon, Wallace's opponent, wished to distance himself from extremist optics, but his policy on policing was no different than his far-right opponent's. What separated the two men is that Nixon got to put his plan into action. Nixon's expansion of law enforcement powers constituted not only a response to black protest but also an escalation of the war on drugs. As Nixon told it, narcotics were rotting once clean, respectable communities inside out. Hard-nosed, no-nonsense policing was required to come down on illicit substances as hard as humanly possible. But this crusade failed to make a dent in the number of drug abusers on the streets. The FBI estimate that in 1980, 600,000 people were arrested for drug offences. In 2019, that number was 1.6 million.

However, there is documentation of an ulterior racist purpose to this empowerment of the police. The architect of the war on drugs and Nixon's domestic policy advisor was John Ehrlichman. Journalist Dan Baum recalls Ehrlichman telling him:

"The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. [...] We knew we couldn't make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did".

H.R. Haldeman, Nixon's chief of staff, wrote the following:

"President emphasized that you have to face the fact that the whole problem is really the blacks. The key is to devise a system that recognizes this while not appearing to".

Historians have described Nixon's war on drugs as being motivated by more than racial prejudice. Still, it was evident as a factor in the deployment of police against non-white people. Heather Ann Thompson, a historian at Temple University, explains:

"Politicians decide that protests against things like police brutality are exactly the same thing as crime — that this is disorderly. This is criminal. And so, police are specifically charged with keeping order and with stopping crime, which has now become synonymous with black behavior in the streets. The police, again, become that entity that polices black boundaries".

This is the law enforcement system in place in America to this day. A 2020 study from the ACLU found that despite comparable marijuana usage rates between black and white people, black people are 3.6 times more likely to be arrested for possession. During the war on drugs and the era of "law and order", the poor and black have further been endangered by the police's militarisation.

In the mid-60s, Daryl Gates, who was partly in charge of the LAPD's response to the riots, introduced SWAT teams to America. He developed the concept in collaboration with US marines, and the specialists he trained for this job were mostly ex-Korea and Vietnam veterans who he educated in military tactics. From the sound of the starting pistol, SWAT was a primary participant in riots responses, and soon, the war on drugs. Gates later became LAPD chief and went in front of a Senate Judiciary Committee to tell them even casual drug users were guilty of treason and should be "taken out and shot". In 1997, the American government enacted the 1033 Program, allowing police access to military equipment free of charge. Since then, they have raked in $7.4 billion in military surplus, including everything from grenade launchers to aircraft.

By 2005, there were 50,000 SWAT deployments in the US annually. Routinely, SWAT excursions consist of no-knock or quick-knock raids. When no-knock raids were first legalised, police abused them so thoroughly, so direly, the decision was quickly reversed, but complex lawyering brought them back from the ashes. In 2015 alone, there were 20,000 no-knock breaches of homes. A 2018 Northwestern University study analysed nationwide data on the practice and concluded that, on average, these SWAT raids neither reduce violent crime nor increase officer safety. They have, however, left a trail of blood in their wake.

In Lima, Ohio, unarmed mother Tarika Wilson was collateral damage as SWAT police searched for a suspected drug dealer. One of them blindly fired into a room Wilson occupied with her six children, killing her, and wounding the baby she held in her arms. The officer was acquitted of all wrongdoing.

In Framingham, Massachusetts, a SWAT team prepared to search an apartment for a drug dealer. Despite finding and arresting him outside the property, they stormed it anyway. Inside, they confronted Eurie Stamps Sr., a 68-year old grandfather who they had been briefed posed no threat to them. According to one testimonial, they ordered Stamps to lay on the ground, and an officer accidentally discharged his weapon into Stamps' head. However, attorneys for the victim's family contest that this is inconsistent with the evidence and would have required bullets to turn corners. Either way, they killed Stamps, and the implicated officer remained on the force.

In Detroit, a SWAT team hunting down an accused murderer threw a flashbang grenade at sleeping 7-year-old, Aiyana Stanley-Jones. An officer then killed her by shooting her in the head. According to a spokesman for the family, the police forced Aiyana's parents and grandmother to sit in their child's blood for hours. All charges against the officer were dismissed.

In Cornelia, Georgia, a SWAT team hurled (content warning for link: real-life injury detail) a flashbang into the crib of 19-month-old Bounkham Phonesavanh. The detonation left Phonesavanh with severe burns and ripped open his chest, exposing his rib cage. The raid retrieved no drugs or arms, and the attacking officer was acquitted. I could go on, but I won't. In all of these cases, the attacker was a white person, and the victim, non-white or mixed race.

The routine tolerance of police carnage begs the question of how they get away with it. The answer is that collective bargaining has allowed police to insulate themselves from the consequences of assault; they benefit from union contract clauses that enable them to sabotage investigations of officers. Depending on the department, they can discard complaints if they take too long to investigate, avoid keeping records of officer misconduct, or have the taxpayer shell out for their legal fees and settlements. In 2019 alone, the American public spent $300 million bailing out police departments for their abuse. In some cities and states, law enforcement set the rules for who can interrogate their officers after an incident, what they can ask, and how long the interview can last. In 41 cities and 9 states, police suspects get access to information before their interrogations which civilians don't get.

A 2018 study from Oxford University looked at the 100 largest cities in the US and observed that the strength of police union protections in an area correlates to the rate of police abuse. More recently, New York police looked for help from yet a higher authority. The Police Benevolent Association is a union that covers two-thirds of NYPD cops. Typically, the PBA refrains from endorsing presidential candidates, but they broke that informal rule to back Donald Trump in the 2020 election. When critics suggested this could cloud their impartiality when dealing with protestors, the union labelled it "hysterical nonsense".

With the NYPD's full-throated endorsement of Trump, law enforcement and white supremacy again intermingled. Trump gleefully tosses about the KKK's old "America first" slogan, barred citizens of seven predominantly Muslim countries entering the states, and called Robert E. Lee, the man who led the war to defend slavery, "a great general". The real estate tycoon has consistently garnered the support of the far-right, including chauvinist extremists The Proud Boys, white nationalist Richard Spencer, and former KKK Grand Wizard David Duke.

In his supporters, rhetoric, and employment of police, Trump harkens back to Nixon, Wallace, and even the KKK. He hinted he would have looters shot, demanded "domination" of protestors, made to pit troops against rioters, and barked about "law and order" policing. For his part, Arkansas Senator, Tom Cotton, called for "No quarter for insurrectionists, anarchists, rioters, and looters"; "no quarter" meaning that you kill the enemy. Again, all this despite 93% of BLM demonstrations involving no violence or property damage. What I didn't mention the last time I talked about the 93% study is that the same research found 54% of BLM protests were met with police violence. If you're a black rights demonstrator in the US today, you're more likely to be assaulted by police than damaging anything.

On paper, Americans have a right to free speech, but in practice, many police forces have tear-gassed or beaten peaceful protestors, they've assaulted journalists attempting to hold them accountable, they've even attacked medics tending to the injured. The use of tear gas in a warzone and of force against medical personnel and journalists are international war crimes.

A 2015 report from Amnesty International found that there is not a single US state in which police use of lethal force complies with international law. Nine states also lack any laws on when police are allowed to employ potentially homicidal measures. The militarisation and deregulation of American law enforcement have come home to roost, and the institution frequently manifests as a domestic army weaponised against civilians. This has only been a very cursory history of American policing. However, a rudimentary understanding of America's law enforcement still allows us to put The Division agency, their enemies, and their methods in a historical and political framework.

The game has the opportunity to acknowledge, as the UoD research did, that we don't all go "every man for himself" at the first sign of fraying infrastructure. It was free to reflect on the desperation that drives many to loot and riot, whether it be food shortages or unequal treatment under the law. But the game couldn't be less interested in these compassionate mentalities and sociological facts. Like Wallace, Nixon, Trump, and the police unions, it massages a lie of psychopathic street militants into a justification for a more viciously equipped and less accountable law enforcement.

The game doesn't have to pretend that every looter is a starving family man or that if society does collapse, it'll all be people sitting around braiding each other's hair and singing kumbayah. But in moving to the opposite extreme, it ends up validating a hateful and predatory ideology. It says that safety is to be found in increasing law enforcement's capacity to kill at the same time as lifting safeguards that might prevent their abuse. And abuse is the consistent pattern with US police. In the play of Ubisoft's RPG, we are judge, jury, and executioner to American citizens, amassing an ever-more fissile armoury as our body count rises. We even get the riot armour, tear gas, and flashbangs which police use to brutalise so many innocents to this day.

The Division further praises real and disturbingly authoritarian legislation. In the USA, the head of state can issue "presidential action emergency documents". These documents let the President establish secret protocols that they can enact in a crisis. They could have the ability to impose censorship, martial law, or any number of other oppressive measures that remain hidden from the public. The Division mentions one of these documents by name: National Security Presidential Directive 51. The story imagines that it's this legislation, signed into law by George Bush Jr., that founds The Division, allowing for the heroics of the campaign. Representative Peter DeFazio has twice requested to review the full text of Directive 51, and Homeland Security has blocked him on both occasions.

I didn't explore The Division's private military company in this essay because they were so close to the "goodies" that it would be redundant. Both The Division and the LMB are pack mules overburdened with firearms imposing martial law under the transparently poor-faith shroud of "security". The only distinction between the two is that The Division is the killing squad that went through the official channels to carry out massacres. For both the real government and The Division, authority's approval of the violence is all that's needed to wash the blood from their hands.

While, so far, we've discussed how the game uses arguments that empower racially abusive organisations without talking directly about race, we must also recognise that that all changes with the Rikers faction. The one prominent black character in the game is Larae Barrett, den mother to the Rikers. The gang proudly describe how Barrett taught them to take everything they could from society, invoking the paranoia of black people as thieves; their grand conquest was the NYPD HQ. Based on the logs we collect, the Rikers' two favourite hobbies are torturing cops and talking about torturing cops. The game has an overblown obsession with police persecution which mirrors the current "Blue Lives Matter" movement. The Division imagines a naked cruelty against police that necessitates a kind of hyper-cop that could redress the balance of power. But this is not an accurate description of the relations between law enforcement and prisoner.

As with "rioters", it's easy to let your imagination run wild with thoughts of the hardened criminals gnashing at the bars of Rikers. The ugly truth is 85% of people in the modern-day Alcatraz haven't been convicted of a crime. They're held there awaiting trial, and the Rikers guards are notorious for beating these prisoners with little or no provocation. In 2014, the Justice Department published a report after a two-and-a-half-year-long investigation into the prison and found a "deep seated culture of violence" with its sights trained on adolescent inmates. In 2014, 77% of the severely injured had a mental illness. Despite promises to reform and a shrinking prison population, this guard violence increased by 54% from 2016-2019.

Rikers is also physically and mentally unsafe for inmates. Temperatures in the summer can exceed 90°F (32°C), and inmates have reported being regularly denied cold water. The facility is adjacent to a power plant that spews out thousands of pounds of toxic pollutants annually, and water and sewage systems keep failing because the buildings are constructed atop a landfill. The landfill gushes flammable methane into the buildings, and in 2020, coronavirus spread through the prison population at 50 times the national average. We haven't even got to the kicker that in 2017, 92% of Rikers inmates were non-white.

Never mind that in 2017 being a fisher, logger, or roofer was far more dangerous than being a cop or sheriff's officer. The Division sees the enforcers as victims and calls killing Rikers refugees "bringing them to justice". The Joint Task Force, who we fight alongside in the game, chant for the former inmates to go back to the prison most of them weren't sentenced to in the first place. I don't know what you would call this except racism. Some defenders would respond that the shooter is not endorsing these law enforcement approaches, just depicting them, but we can easily debunk that.

Our in-game critics are there to be won over (e.g. Paul Rhodes, the engineer in charge of turning NYC back on), to look like cranks (e.g. Rick Valassi, the conspiracy theorist), or to die (e.g. almost everyone else). Medical Expert Jessica Kandel gives us her stamp of approval, and before we've lifted a finger, 9/11 hero Roy Benitez is writing love letters to our sleeper cell. The apocalypse never quite reverses under our hand, but starving people on the street sing our praises, hospitals are outfitted, and by the end, jolly children are running about our ankles.

The Division and many other rose-tinted tributes to militarised law enforcement make their killers look like heroes by having them operate in a universe without bias, collateral, or social nuance. They try and sort citizens into the categories of either criminals or people who require help, which is silly because you can find no shortage of people who are both. Moreover, you'll notice that in this family of media, protagonists spray munitions in all directions but never hit an innocent. There is no battle in The Division where you can think you're shooting a violent murderer and find you've killed a Mum of six. There is never a mission where the agency's internalised racism leaves an innocent black body on the pavement. If there were, and realistically, there would be, militarised police would start looking a lot less appealing.

Among left-leaning gamers, the notion that Ubisoft's titles are "apolitical" is discredited enough that it's a punchline. However, I wanted to write this essay to shine a light on just how deep this politicising goes. The Division isn't just bandying about conservative memes; we can track the ideas it espouses back to specific leaders, campaigns, legislation, policies, special interest groups, movements, and conflicts. Because it is through these phenomena that political ideas are created and realised.

We can't talk about Christmas without evoking Christianity. We can't depict pyramids and tombs without referencing Ancient Egyptian dynasties. Similarly, a game cannot talk about dispatching a domestic army against US citizens without invoking the history of militarised police. A story cannot paint an image of animalistic rioters without harkening back to the mindsets of white supremacists like Nixon and Trump. To cite historical entities is not to espouse a particular opinion of them, but how you treat them does. The Division is not fascist for simulating the authoritarian injustices of America's past and present. However, it becomes authoritarian through affirming myths that dehumanise non-white people and championing law enforcement approaches that scar vulnerable communities. Thanks for reading.