Right on Cue: An Analysis of Side Pocket (SNES)

By gamer_152 1 Comments

Providing informed, up-to-date information about video games means running all the big new names on my machines, keeping on top of every fresh release, and that's why I've been playing 1993's Side Pocket for the SNES. At least, it says "Side Pocket" on the title screen. Here's a question: How do we know when we have two distinct games and when we have two versions of the same game? I'm bringing this up because in reviewing Side Pocket, we contend with an old ambiguity: in the ancient days of the medium, a lot of games received ports that deviated sharply from the original works they were based on. And in other circumstances, we got games so similar they could have been ports, but they were given different names.

The name "Gauntlet" refers to an arcade release and a NES port of that game, among other console adaptations, but the two games use a totally different set of levels; the arcade version has an earthy, textural art style, while the NES version is flatter. The NES software also includes a soundtrack, while the arcade cabinet has no in-level music. But then Oh Shit! is just a copy of Pac-Man, or there's the famous Doki Doki Panic/Mario Bros. 2 switcheroo, where one platformer is a mild tweak and a sprite swap of the other, but the words on the boxes partition them into different series. This manner of arbitrary naming schemes confuses the discussion of Side Pocket and its spin-offs. The original Side Pocket is a pool game released for arcades by Data East in 1986, and then gradually ported to the NES, Game Boy, Mega Drive, and WonderSwan. Data East also contracted Opera House to make a Game Gear version, and Iguana Entertainment adapted the software to the SNES. All these games had significant variations.

Iguana Entertainment was founded by Jeff Spangenberg, a former programmer on the Amiga ports of Space Harrier and After Burner, who used his pet iguanas Spike and Killer as the company's mascots.[1] The company's logo at the time of Side Pocket was this sick picture of one of these lizards wearing sunglasses:

The proof that Opera House worked on Side Pocket is elusive. As far as I can see, their name doesn't appear in the game or on its box, but on their old website, they do claim Side Pocket among their products. Pretty straightforward so far. But in 1987, Data East released a game based on Side Pocket in Japan and called it Pocket Gal. While the title would lead you to believe it's a handheld version of Side Pocket, it's actually an arcade variant of it, despite Side Pocket having started as a coin-op.

Then there's Data East's Minnesota Fats: Pool Legend, which sounds entirely unrelated to Side Pocket but which the firm published in Japan under the title Side Pocket 2: Legend of the Hustler because it sandwiches Side Pocket gameplay in between original cutscenes. Only the Mega Drive Minnesota Fats uses pixel art cinematics, and the Saturn port is an FMV game. The character of Minnesota Fats was abducted from novels by Walter Tevis, the author of books like The Color of Money, The Man Who Fell to Earth, and The Queen's Gambit. We will probably never know whether Minnesota Fats was based on a real person or the real person was based on Fats. American pool hustler, Rudolf "Minnesota Fats" Walderone, claims that Tevis named the fictional character for him, while Tevis protests that it was the other way around. Either way, it's not a coincidence that Data East downloaded the fake Fats into their games. A couple of the characters in the Mega Drive version of Side Pocket are undoubtedly inspired by Tom Cruise and Paul Newman in the film version of The Color of Money.

We have a diverging root network of Side Pockets here, all of which (besides the original) may count as versions of the original game or sequels, depending on your perspective. I want you to know that for three reasons: Firstly, it means Data East squeezed the absolute maximum out of this one lemon. Maybe it's a good thing; you'd unlikely be locked out of Side Pocket because of the console you bought. Secondly, whether two games have been called by the same name or different names has often been a matter of branding. But we're not marketers; we're players. Our primary concern is not business; it's the art, rules, and sound of this media. And if we start identifying games as being similar or dissimilar based on naming conventions, we're confusing labelling for content.

Most importantly, I'm talking about all of this because I'm lazy, and I can't unpick all the divergences and convergences between these twelve pool games. I have to be places. I have to buy groceries. So, I'm only reviewing Side Pocket for the SNES. And while some of the observations I'll make about this port can be made about all the pool games I've named, others can't be. It might sound more sensible to start from the beginning and write a blog about the arcade Side Pocket, but because the series picked up level types and presentational accents over the years, the later Side Pockets give you more to explore.

Side Pocket and cue sports in general are somewhat shooters. You have targets, and you need to aim your projectiles at those targets. But what you won't find in another shooter is the ability and requirement to adjust the velocity of your shot or the duty to think about its knock-on effects. In Berzerk or Jet Force Gemini, your bullet stops when it reaches your target. In pool, targets (balls) can also be projectiles, and your initial projectile (the cue ball) may gift some of its velocity to those projectiles. This donation is the only means to hit your eventual target (the pockets), as it's against the rules to punt them directly. But calculating the right force with which to hit a projectile is tricky as, unlike in a standard shooter, friction slows objects in motion over time. Further, all projectiles can ricochet off walls. So, the question of the game isn't "Can I hit my target?". It's "Do the physical aftershocks of hitting this target get the right projectile to the goal?".

Abnormally for a shooter, pool does not separate movement from firing. We must play our base projectile from its current position, or a respawn point if we pot it, and with every shot, we relocate that bullet. This fixed positioning, combined with the possibility for some coloured balls to block others, means that, like in grid-based strategy games such as Invisible Inc. or Banner Saga, we can't make moves solely because they are fruitful in the moment. We have to consider whether the resulting positioning of our pieces those moves create is acceptable, as that positioning decides what moves players can make in the following turns. Pool needs six hoops spread around the perimeter of the table because, with balls perpetually changing positions, it can't guarantee that during a shot, you'll have access to any particular one. More like Front, Back, and Side Pockets. But in Invisible Inc. and Banner Saga, interactions between pieces are based on stat logic, whereas in pool, conflicts are resolved through physics. You can even conceptualise pool as a procedurally generated physics puzzle.

Side Pocket is not straight pool, though. It does for its sport what NBA Jam did for basketball. Working in the post-realistic laboratory of video games and conceiving of pool as an original product, Data East had the opportunity to throw in whatever zany flourishes came to mind. What if pool was now a single-player game with lives, and you lost one for every shot on which you didn't sink a ball? What if sometimes, the highest value ball would start flashing, and when you hit it, it flew around the table at turbo speed, tossing the table salad? What if when there was one ball left on the felt, a vortex appeared in a pocket, and if you potted the ball in there, you were transported to a magical bonus zone? Some of the designers' ideas pan out better than others, but in general, their disregard for common sense makes Side Pocket a joy to behold.

Sports are generally not considered up for redesign the way that board and card games are, and that can be unifying. The community for rugby is not divided by whether they prefer Super Rugby II Turbo, or Virtua Rugby 5 Ultimate Showdown, or any one of thousands of other permutations of the sport. There is a singular set of mechanics shared between people across space and time, or at least only a few sets of mechanics. Shared rules create a shared community. At the same time, this feels like a bit of a wasted opportunity. If we use game design in other domains to refine and put new spins on existing play, then why not in this area? We need additional maps for soccer. We need tennis triples with multiball. We need pool with combos. And video games can give it to us, introducing and enforcing new rules with smooth automated processes.

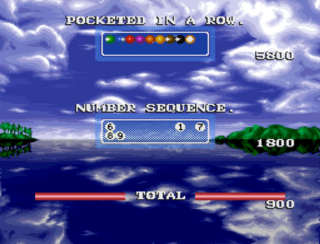

There was a pre-existing connection between the NBA Jam approach to sports and Iguana, by the way. The company was a natural fit for porting Side Pocket to the SNES as it had made the console versions of NBA Jam. I didn't make up "pool with combos", either. If you wanted to give 9-ball pool a dressing down, you might admonish it for having such predictable progression. You pot the 1 ball, then the 2, then the 3, and on up to 9. There's no room for strategic deviation from these numbers. In 1993's Side Pocket for the SNES, developed by Iguana Entertainment, published by Data East, you can pot the balls out of order. You can even pot the cue ball. The catch is that Side Pocket's story mode takes place over multiple levels, and each sets a minimum score requirement for graduating to the next. Sinking balls grosses a trickle of points, but the gushing aquifers of score are the combos. You get a bonus for pushing numbers into holes in numerical order and potting balls on consecutive shots. So, if I pot the 3 ball, then 4, then 5, that's a combo. But also, if I pot balls on shots 9, 10, 11, and 12, that's a combo too. The longer your runs of balls, the fatter your bonus.

Now, we have the lifeblood of any engrossing strategy play: difficult questions. Do you think you have a better shot at potting balls consecutively or potting balls in order? Can you afford to break a combo if it gets the cue ball into a more opportune location? Like all games with questions that stay interesting, Side Pocket's work because how you answer them changes a lot as the game state evolves. Your methodology is based on the volatile configuration of the table. But the game's combo system is also one of those ideas that doesn't fully pan out. You can't make informed tactical decisions without the "information" bit, and because you don't receive your bonus points until the end of the level, all you can do is make an educated guess about whether you're on the fast train to parsville. There's also not that anticipation of closing in on the score cap, or biting your nails as it looks like the game could go one way or the other, because you're not seeing your total score while you play the frame.

You also don't have reins on the physics during those "super" bonanzas where the balls are ricocheting off every surface like it's Hungry Hungry Hippos, but you can always choose to evade the supers. There is another, unavoidable, snag in the mechanics. From Pocket Gal, Side Pocket picked up the idea that the player should perform trick shots at the end of a level, after the games of pool. To make these trick shots, you must sink all balls, not hit them into any of the marked forbidden pockets, and where applicable, refrain from making contact with any glasses on the green. There are bonus lives on the line in these levels, which you'll probably need, but the real kicker is that from the second stage onwards, you need to make these shots for your ticket to the next city. It makes for a neat structure. Sandbox challenges are stacked in between prescriptive assignments, meaning the gameplay is frequently changed up.

Unfortunately, the stunt levels don't allow for creativity in pursuing your goal. You need to be a certified Rudolf Wanderone to pull off these party pieces, and the price for missing is extortionate. While elsewhere, the game accepts that you might need to take more than one swing to down a ball, here you have only a single life, despite the bar being set higher than during a standard frame. There's a trick shot in which you must make your cue ball curve around in a "C" shape to hit your target. And if you fail, it's not just lives that hang in the balance: you must restart the stage, including the normal pool games, from scratch, frequently expending more lives to requalify for the bonus shot.

Me and you have a privilege the 1993ites didn't: we can look up the trick solutions on YouTube, and the game grants you a slim mercy in letting you practice them outside of the campaign. However, tiny alterations in where you hit a ball and how much force you apply cause pronounced changes in its trajectory. You see that power meter at the top of the screen? The one that looks like it's displaying your phone signal? You can take two different shots that will fill the same number of strips on that meter, and the outcome will be different in each because the millisecond on which you press the A button matters. It's due to the trick shots that Side Pocket is worth playing but not worth finishing.

But if you do load it up, take some time to admire how Side Pocket steers clear of pure simulation and, ahead of its time, establishes a vibe. You are not just a competitor; you are a nomad of the cue, travelling the long open roads between US metropolises, and sending locals swooning with your dexterity at the table. Although only in the coastal cities; there are no games to be won in the South or Midwest. When playing, I would pretend this was due to the central US being wiped out in a pool-based cataclysm that came to be called The Great Sink.

As you lean over the mahogany rails, lining up your angles, a dignified jazz soundtrack plays. It's a change of timbre from the arcade and NES versions, which use chirpy singsong soundtracks, and from the Game Boy iteration with its piercing and confrontational music. The Mega Drive port fabricates a combination of all these sounds. The satisfying clack of the balls is present across almost all versions, even the handheld WonderSwan's, although it's not extant in the Game Boy port. The colours on the Mega Drive version look more washed out than those of the SNES, but it does provide a smidge more shading on the balls. It's something the arcade version does shockingly well, too, even if the picture in that game looks a little overexposed. Still, given that pool has such vivid equipment, the greyscale screens of the WonderSwan and Game Boy suck the life out of it. Wait, I said I wasn't going to do this.

Truthfully, SNES Side Pocket's cultural impression of pool feels a bit out of touch. Here, you have the quintessential activity of the seedy dive bar, the playground of the weary hustler, but Side Pocket imagines a game of pool as something that men attend in waistcoats and ladies crane their necks over wearing elegant evening gowns. I guess we should talk about the women sticking to you like flypaper in all these games. Back into the Side Pocket multiverse. In the early Side Pockets, pool was a language of seduction which brings beautiful women flocking. In some versions, even bunnywomen. By the time of Pocket Gal, the series is full-blown pornography. It depicts a chilling alternate history United States, where pool tables are sexual battlegrounds. Women are so overcome with lust at your adeptness if you win against them, they'll remove their clothes on the spot.

Side Pocket for the SNES is tame by comparison, but still features portraits of all these female barflies because of the Pocket Gal legacy. Women who are 50% hair conditioner stare at you doe-eyed over drinks, yet the gender relations never get spicier than that. Although, sometimes, the flirtatious window dressing verges on body horror. In the HUD, a floating pair of lips mime speaking, and the "trick shots" mode has this sliding tile puzzle where you're rearranging a woman's face. Best not to think about it.

And that's Side Pocket, warts and all. So, where are these companies now? Iguana Entertainment was bought up by Acclaim in 1995, which renamed it "Acclaim Studios Austin". That year, Acclaim also purchased Sculptured Software, which had ported games like Doom and Mortal Kombat to the SNES.[2] They refashioned Sculptured as a second location for Acclaim Austin under the name "Iguana West", although later changed the name to "Acclaim Studios Salt Lake City". Acclaim Salt Like City would go on to produce their own original NBA Jam: NBA Jam 99. Acclaim Austin, meanwhile, birthed the Turok games, some of the 00s's most respected lizard violence entertainment. Its founder, Jeff Spangenberg, was fired in '98 and went on to found Retro Studios, the Metroid Prime developer.[1] Acclaim Austin had its throat slit shortly after Acclaim went bankrupt in 2004. Data East had gone belly up the previous year, and many of its licenses fell into the hands of Japanese mobile gaming company G-Mode, which became a subsidiary of Marvelous.

Marvelous was all over the place, developing Harvest Moon games, publishing Rune Factory instalments, and producing Japanese Pokémon arcade cabinets no one has ever heard of in the West, like Pokémon Ga-Olé. G-Mode's inheritance from Data East included Side Pocket, the SNES version of which they license out for the Switch. Unlike a lot of other publishers, they're not sitting on this classic IP; they're putting it to use. In 2018, Marvelous even had a number of their properties, including BurgerTime and Heavy Barrel, fused into the retro remix Heavy Burger. And wouldn't you know it, nestled among the other machines in Heavy Burger's virtual arcade, there was Side Pocket, still clacking all these years later. Thanks for reading.

Notes

- A Retrospective: The Story of Retro Studios by Kenneth Kyle Wade (June 16, 2012), IGN.

- Sherman, C. NEXT Generation, Issue 13 (1996). Imagine Publishing (p. 25).

All other sources linked at relevant points in article.