The Invention of Fire: Discovery in Outer Wilds

By gamer_152 3 Comments

Note: The following article contains major spoilers for Outer Wilds.

When media portrays science, it's often as an aesthetic. The on-screen face of the discipline is laboratories and white coats, beakers and robots. Which is fine for entertainment purposes, but if you want to boil science down to its essence, you can't treat it as stylisation. Sometimes, fiction depicts science as a body of knowledge, as everything we know about physics, chemistry, and biology. That's part of the picture, but we're still missing a crucial component. Science is not just a library of information; it's also the method through which we fill that library. It is starting from a position of total scepticism and using only logic and experiment to confirm or deny hypotheses. I'm not sure I've ever seen a piece of media as cognizant of that methodology as 2019's Outer Wilds.

Outer Wilds' player character is one of a fish-like humanoid species called the Hearthians, who live in a solar system substantially different to ours. The game begins on the day of the protagonist's inaugural flight in this society's thriving space program. Their home planet of Timber Hearth is ramshackle, and its astronautics improvisational and foolhardy. Its history is full of reckless rocketeers who half blew themselves up trying to touch the heavens. But the Hearthians are also intelligent and inquisitive. They've discovered that the universe is expanding and have translated the language of the long-dead Nomai race. The Nomai are a point of fixation of the Hearthians. Furry, four-eyed travellers who entered the solar system long ago, the Nomais' fate remains a mystery. However, as we prepare for blast-off, one of the statues the Nomai left behind opens its eyes and stares right into our main character's soul. Then, it's off to the stars.

The game confidently eschews a prescribed order in which to complete most of its tasks, instead letting you galavant about the solar system as you please. You venture where you want, when you want, surveying ancient alien ruins and reconstructing their exploits one stone tablet at a time. Although, the lessons you glean from one expedition may help you access information on another. You can also visit fellow Hearthians on neighbouring planets, where you'll find them warming themselves by crackling campfires and jamming on their twangy instruments.

And then there's the big twist, the one for which Outer Wilds is famous. If twenty-two minutes pass during any one of your runs, your planet's sun goes supernova. When that happens, or if you fatally wound yourself before then, you see a sped-up, reversed replay of the whole session up to that moment. Then, you wake up where you started: standing in front of a campfire on Timber Hearth, ready for lift-off. No one remembers the events of each time loop except you, your ship's computer, and an unflappable Hearthian called Gabbro. If you can commit to hours of experimentation and exploration across these cycles, you can feast on Nomai culture and learn of its deep roots in science and engineering.

Here's the abridged version of Nomai history: They travelled to the solar system, tracking the signal of a stellar object called "The Eye of the Universe". When the Eye stopped transmitting its siren call, they were left at a loss, but were able to bootstrap a "Probe Cannon" to locate the Eye. Central to their research was the "Ash Twin Project", a data storage technology which used a Nomai "warp core" to send information back in time and save it. This miraculous computing required the energy of a supernova to function. However, a comet called "The Interloper" soon soared into the Nomai's stellar neighbourhood, releasing a cascade of deadly matter that wiped them out before they could complete their work. But we're getting ahead of ourselves because to discover any of the universe's history, we must first master its physics.

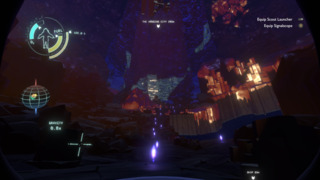

Most fundamentally, some grasp on Outer Wilds' physics is necessary because if we want to explore ancient settlements, we have to be able to reach them in one piece. Crossing the distances across and between planets requires the use of a newfangled jetpack and a spaceship that's like an outhouse with a propane tank strapped to the underside. The acceleration, braking, and course correction of both happen on a delay, meaning we must be able to predict where our momentum will carry us long before we get there and counteract that force accordingly. Accidentally slamming your craft into the ground at full speed or boosting out of a planet's gravity are part of your initiation. You walk in the footprints of the real humans who had to tame rocketry and aeronautics to travel beyond Earth's atmosphere. Outer Wilds comments that any extraterrestrial anthropology or archaeology would have to begin as an application of physics.

When we say "physics" with reference to computer games, we're often talking about only a subset of the real subject. In gaming lingo, physics is how our avatar responds to inputs and how the game resolves kinetic interactions between entities. In the real world, physics does include the maths of everyday objects pushing and pulling against each other, e.g. the velocity of a barrel rolling down a hill or how high a ball will bounce when you drop it. However, in our world, physics is also the word for the rules everything material in the universe follows, as well as the frameworks in which we place those rules. It's the phenomenon of opposite charges attracting, it's the definition of a black hole, it's what radioactive decay produces which particles. And in Outer Wilds, it's these kinds of laws that players need to internalise as much as the swaying and rebounding of objects.

You must be able to identify that strange matter appears near green crystals, know what the power source of the Ash Twin Project is, and recognise how quantum objects move. Outer Wilds forces us to acquire and apply knowledge to overcome problems rather than using superior tools to strong-arm through them. It does that by rarely upgrading our character. Our protagonist doesn't come with a stat sheet or talent tree enclosed, and the single equipment augmentation they get is a modest patch to their radio scanner. So, almost all progress requires us not to return to an area with a keener blade or more developed skills but with new ideas on how to mine their secrets.

For example, once you know what an entrance teleporter looks like, you can start blinking yourself into buildings you were previously shut out of. Once you know jellyfish can insulate you, you can piggyback on one to safely pass through an electrical field. Just as getting a feel for your ship is a process of trial-and-error, you tease many of these rules out of the universe through experimentation. The only way to be sure that jellyfish can protect you from shocks is to try and use one as a shield. In a lab on Ember Twin, you can employ purple warp cores to create black holes and white warp cores to create white holes. You're also able to shoot your probe into a black hole there and watch it emerge from a white hole. It's possible to infer from those experiments that when you see a purple warp core in a teleporter, you can enter it, and when you see a white module in the same mechanism, you can exit it.

This hold on physics is not just our key to the solar system's secrets. On each of the planets and space stations, the developers toy with motion and interaction in a different way. So, to grasp the physics of Outer Wilds is to understand its setting.

- Timber Hearth is mostly a neutral entranceway into space but also has geysers that can send you soaring into the air.

- Ash Twin and Ember Twin orbit each other in addition to circling the sun. They also exhibit an effect in which sand flows from one onto the other, revealing ruins on Ash Twin as Ember Twin's are buried.

- Nested in the centre of Brittle Hollow is a black hole. The Hollow is bombarded by volcanic rocks from its moon, which cause its surface to fall into the vortex chunk by chunk. Areas of the planet can also become accessible or inaccessible over time due to this disintegration, while its core teleports us to the Nomai's "White Hole Station".

- Giant's Deep is an oceanic sphere dominated by tornadoes. Those twisters can lift islands into the upper atmosphere before they fall back into the sea.

- Dark Bramble is a series of nested spaces that are bigger on the inside than the outside and where predators float in the atmosphere itself.

- We can slide about on the icy surface of The Interloper, the comet having become stuck in the sun's orbit. When it approaches the star, part of its surface melts away for a brief moment, allowing us passage to an interior of cavernous slides and hazardous materials.

- The Quantum Moon is a devious trickster which changes the planet it's orbiting when we look away. To land on the moon, we must stare at a photo of it on entry, and we can only reach its mythical North Pole through a teleporting temple on its soil.

Gravity on any of these bodies is also proportional to their mass, as in reality. So, you can float like a feather on The Interloper or the Hourglass Twins, but you feel like you're wearing lead boots stomping around Giant's Deep. The non-euclidean maze of Dark Bramble and the various space stations are without gravity entirely.

Schools generally teach us to sift out Earth sciences from abstracted physics. Yet, the specifics of any physical process on a planet are down to the rules that govern its matter, its energy, and their interactions. That is true whether we're talking about the quantity of rainfall, the evolution of birds' wings, or the polarity of the magnetic field. Outer Wilds represents this relationship between the physical nature of a planet and what happens on it through mechanics that are easily understood. The physics of the worlds are also memorable both because they are interactively tangible and because we must work around them to make headway. If you're liable to get flattened by a meteoroid or hurled into the upper atmosphere, you'll pay a heavy cost for not knowing about it.

To internalise the physics of Outer Wilds is also to be conscious of the culture and life's work of the Hearthians and the Nomai. It says a lot that the most advanced building on Timber Hearth is the observatory. That they don't have theatres or stadiums or even brick houses, but they do have a space program. That judging by their anecdotes, they risk life and limb trying to blast themselves into space on a ton of rocket fuel. The game depicts the Hearthians as loveable pioneers, complete with banjo and roasted marshmallows. They're goofy in their proneness to accidents but noble in stopping at nothing to press their boots into the clay of distant planets. When we find other members of our species off-world, they're content despite being hundreds of miles from home because they're the chosen ones who got to explore regions of their domain others might never see. Even Riebeck, who quivers in his boots at the prospect of spaceflight, considers it worth pushing beyond his terror to spelunk the ruins of a long-forgotten city.

By comparison, the Nomai know a lot more than the Hearthians about the principles that control the universe. They also more capably concentrate those principles into new technologies. Still, the two peoples hold the same incandescent enthusiasm for scientific inquiry. For the Nomai, the Eye of the Universe is a secular Holy Land. There's a common opinion that science cheapens the natural world by demystifying it, but that's not how these fuzzy extraterrestrials see it. To them, theories that objectively describe the universe put them more closely in touch with a divine celestial. And without a working knowledge of physics and engineering, there is no pilgrimage for them. So, standing around a blackboard, prototyping power sources is as culturally gainful for the Nomai as reading scripture might be for a society steeped in the supernatural.

As a Hearthian, our missions and values align with those of the Nomai, making it easy to empathise with them. The game wishes to impress on us the awe that fills them as they behold the universe, not just as a wishy-washy "out there" space but also as an environment of overlapping physical mechanisms. The one surviving Nomai we can meet, Solanum, has a name that suggests her species illuminates the unknown. Eyes are also a recurring motif in Outer Wilds. The Hearthians have three eyes, and the more advanced Nomai have four, symbolising their clear-headed perception of reality. The Nomai questing for the Eye of the Universe is a metaphor for their goal of gazing at the cosmos as it truly exists. The Nomais' wonderment at nature leads them to research it studiously, and that research produces life-changing technologies.

The crowning accomplishment of the species is their manipulation of black holes. We can just about imagine one translating our spatial coordinates, but the Nomai have been able to use them to alter their temporal locations too. When teleporting each other around the system, the Nomai discovered that commuters would reach their destination a fraction of a second before leaving their point of origin. This is the time travel; the teleporting passenger was able to jump a fraction of a second forward in time to arrive just before they should have.

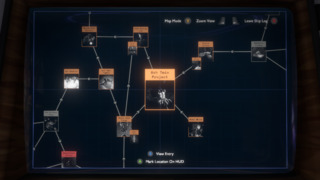

Outer Wilds' real stroke of genius is understanding that time travel, at least within the particular rules of this fiction, is not just a transportation technology but also an information technology. That is, it doesn't just allow us to change our acceleration along the timeline or reverse our direction; it also has the potential to transform what we know. The Nomai are able to exaggerate the teleportation delay they observed up to a period of twenty-two minutes. This trick becomes the crux of their search for the Eye of the Universe. A computer fires a probe in a random direction, and that probe then uploads its data to the Ash Twin Project. The Ash Twin Project then sends the data back in time to before the craft launched. At that point, either the probe has found the Eye, or it hasn't. If it has not, the Probe Cannon knows not to check that direction again and fires in another random one, again sending the data back to the moment before the firing.

Sequentially, the system builds a list of "wrong" locations, and the process continues until the Probe Cannon gets a positive hit. Assuming that you can send information back in time and that acting on that information does not erase any portion of history, you effectively have a means to know the result of any future experiment immediately, no matter how long it takes. Such technology would obviously be of immeasurable value to any scientist and is symbolic of the trial-and-error science relies on. This data recursion is also how the "time loop" of Outer Wilds' universe works. We can think of the Ash Twin Project as a mainframe and the Nomai's statues as terminals. Both Gabbro and we were lucky enough to "link" with these statues. Now, anything we find out in one run gets uploaded to its cloud, and then the "us" twenty-two seconds in the past downloads that information and can act on it. The same rule applies to our ship's database.

While repetition is Outer Wilds' greatest strength, it's also its most humbling weakness. The low points in this sci-fi are the no man's lands in which the eureka moments of discovery give way to experimental grind. It might seem hard to believe that you could get stuck in a rut because most of the solar system is empty void, meaning there are initially few obstacles between us and our target planets. This free ticket to go anywhere we want is closely linked to the wide potential for discovery in the game. A real scientist isn't born with a laundry list of objectives to complete; they must decide which goals are meaningful for them to pursue and what experiments are necessary for their pursuit. Likewise, Outer Wilds has a solar system unfold in front of us like intricate origami, and there's no primary mission weighing on our minds; there's only the destination we pick and the activities we think are worthwhile to perform there.

At first, the time loop mechanic greases the wheels of exploration and discovery because now you're not just seeing what exists at different locations but also times. The game engages you in all four dimensions. Early on, the resets also provide a safety net enabling experimentation. If one of your bright ideas goes down in flames, you can just rewind the universe's tape back to the start and try again. So why not see what trouble you can get into and take a few chances? Jetting off into three-dimensional, mostly empty space further means that we don't have to backtrack through areas to get to a planet; we can fly right to our destination. That's a huge relief when we get set back to the starting area at regular intervals. Initially, having our bungee cord routinely snap us back to Timber Hearth also encourages us to pick new headings and not spend too long poking about where we're unlikely to make swift progress.

But once we tick off all the quick and effortless jobs, the ones left generally require delving right into the heart of worlds and staring at the same puzzles for minutes on end. Here, the time loop goes from sweetening the explorative pot to souring it, as we're jolted back to the very beginning of the game every twenty-two minutes (max). Then, we have to retake the journey, often a long journey, to the site of our experimentation. When we get to those sites, we often find other time sinks.

On Ember Twin, you crawl dark caverns which look highly similar whatever way you turn. Some objects within them can teleport, and in one area, your path is blocked by a deep pit you must patiently wait to fill with sand. On Ash Twin, you have the opposite problem as you may need to wait minutes for the wind to carry away the desert facade, excavating its towers. On The Interloper, there's only a narrow period in which its icy shell cracks, and you can slip inside. You have to determine when that is by trial-and-error. In Dark Bramble, you need to sneak past the Anglerfish without an exact concept of what volumes they can hear at. Make an engine burst fractionally too strong, and you'll be fish food in seconds.

For each of these time-sensitive locks, you can arrive too early to the scene and waste minutes standing around or overshoot the window and have your time wasted by cycling back around to it. At its worst, the loop throws you off the scent of answers because it becomes so arduous to keep reinvestigating the same spots that it feels like the game is trying to tell you you're barking up the wrong tree. And it's boring to keep hitting restart. Therefore, you can lose interest in the experiments.

Look, a lot of scientific work is laborious. It's the "Aha!" moments that get romanticised, but physics is not all jumping out of the bathtub screaming, or running across the university courtyard, papers in hand. Diligent researchers may also stay up all night double-checking calculations, or their job might be testing lab samples eight hours a day. There's room for a game that depicts that steady and mechanical expansion of knowledge, but not in an otherwise optimistic and revelatory sci-fi epic. With its starry-eyed trail-blazers and anthemic soundtrack, Outer Wilds isn't trying to be a mundanity simulator like The Longing or Presentable Liberty. It wants to be the video game Carl Sagan would make. When Outer Wilds does get monotonous, it's also not true to the tedium of STEM labour. It feels less like robotically running through batteries of lab tests and more like having to drive home and then back to the lab every twenty minutes for some reason.

We could also attack Outer Wilds on the basis that it fails to capture the collaborative side of science. Real scientists decode the world by gathering into research teams, publishing in journals, reading other experts' papers, and working together in the same organisations. All of them start by digesting previous generations' findings, and they orient their careers in response to earlier theories. While we might recognise a comparative few people who made exceptional contributions to the field (e.g. Newton, Mendeleev, Darwin), science is not a pantheon; it's a network. So, when you're strapping yourself into your one-seater ship in Outer Wilds and building a private database of geography and anthropology, maybe the play isn't capturing the essence of scientific discovery.

But the title does represent cooperation in its own way. As the protagonist, you're not inventing the wheel. The Hearthians already know a thing or two about the Nomai and the nature of the universe by the time you've earned your interplanetary wings. They've developed a map of the solar system, a space program, and a translator for the Nomai language. When you talk to other people of your species, they freely reference former astronauts and engineers from the tribe, and the Nomai are a font of knowledge who provide most of the information we absorb. We're not inventing cosmology or archaeology from scratch; we're standing on the shoulders of giants.

The Nomai texts are also histories of collegiate endeavours. Even the structure of their writing lends itself to discussion. The way humans and Hearthians do it, you position text in straight lines, shelving one tract above another. If someone else wants to comment on your paragraphs, they usually have to create a spacially independent series of characters next to or after yours. The Nomai begin their documents by writing in a spiral, spinning out from the centre of a stone screen. If anyone wants to comment on that initial statement, they write their text in a swirl pattern that branches off from the initial, which other people can branch off of, and so on. The geometry of Nomai writing makes room for more voices in the same space, which is conducive to the exhaustive dialogues which drive science. The time loop, too, reflects the education of a scientist. On each expedition after the initial run, you are always building atop the knowledge of the Hearthian that came before you.

However, the game's most beautiful ode to scientific cooperation is in its ending. With the Nomai rearranging countless pieces of the Hearthian solar system, it's easy to imagine that the supernova is another synthetic event pushed into motion by their hand. In reality, your sun is just at the end of its natural life cycle. Every main-sequence star is a nuclear inferno, and the Hearthian sun's atomic fuel supply has dried up. All that's left now is for it to make one last, glorious implosion. The Nomai never saw the Ash Twin Project up and running, but it's looping memories now because it finally has the supernova it needs to power it. As it turns out, the Hearthian sun is not alone in its criticality. The universe's stars are one-by-one dying out, and the Nomai have migrated outwards from their home to cling to the few that remain. For all of their space-age technology, the Nomai of the past were not much more prosperous than the Hearthians of the present. Like our amphibians sheltered by their campfires, the Nomai were huddled around dying embers staring out at the infinite darkness.

By the late game, the Nomai ruins have given up countless theoretical treasures, but a clamp on the supernova remains unattainable. It's not in the crashed ship in Dark Bramble with its broken warp core or in the technological marvel of the Ash Twin Project. It's not inside the Hanging City of Brittle Hollow, the probe module of the Orbital Cannon, or even on the North Pole of the Quantum Moon. We can't prevent the death of the sun, let alone the demise of the universe, but we might be able to do something better.

All puzzle games have us transfer knowledge from one challenge to the next, but they generally switch out the objects and environments we operate on as we go. Scientists don't see the same environmental volatility when they try to unravel the universe; they're always describing and engineering the same reality. From a material perspective, humans 20,000 years ago were capable of building spaceships, nuclear reactors, and supercomputers. Everything they'd need to do so already existed on Earth; the limitation was their knowledge.

Representing that scholarly philosophy, Outer Wilds's universe is not just a linear gallery of puzzles. It's also one big puzzle that we are capable of solving from the moment we enter the game. However, we're not going to crack that riddle on the first run because we don't have the intellectual toolkit we'd need to know there is an ultimate puzzle, let alone find its solution. We must take the slow road, gaining the answer through reading and exploration. It is imperative that we understand the problem, recognise how people smarter than us have solved problems before, and then devise a new solution that combines elements of preexisting theories.

If we master the classical physics of piloting our ship, the spooky mechanics of the Quantum Moon, and the general relativity of the black holes, we can put the pieces together and do what the Nomai never could. In one last courageous run, we can take a route to reach the Eye of the Universe. We hop over to Ash Twin, teleport into the Ash Twin Project, and remove its warp core. We then take that power source to Dark Bramble, install it into the Nomai ship there, and input the Eye coordinates from the Orbital Cannon's probe module.

The Eye's entranceway is a stormy wasteland of marbled blue rock, shrouded in darkness, and with a murky concept of "up". Whenever natural philosophers have broken the seal on new branches of physics, they've come upon aspects of the universe that challenged their basic precepts of reality. At various times, that's meant accepting that the conservation of energy can be violated or that the universe is expanding even though it's not expanding into anything, or that one person can travel through time faster than another. I think if we'd discovered any of these phenomena ourselves, we would have felt like reality was breaking down. It, therefore, feels only fitting that that's what happens at the end of Outer Wilds when we make our landmark discovery.

Passing into the Eye's pupil, we find ourselves in a forest where miniaturised galaxies hover before us and then blink out like fireflies. Eventually, we come across a campfire reminiscent of the one at the start of the loop. Nearby, Esker, a Hearthian from a lunar outpost, pops into existence. If we ramble around a bit, we can find a Nomai home with a banjo inside, and picking it up summons Riebeck to the camp. Riebeck is that space-fearing adventurer we met on Britte Hollow, and the banjo is the instrument we found him playing, which he dutifully returns to doing. Next, we find a harmonica to summon Feldspar and a bongo to call Chert, and before you know it, all the Hearthian explorers we found scattered around the system are sitting by the same campfire, playing their music. If you sought the Nomai Solanum out, she joins the party too.

The melodies that you heard each of the Hearthians playing while camping out on distant planets coalesce. They sing a single tune, and shapes begin to form in the smoke above the fire. Then the world goes black, and you are left alone with nothing. And then there is everything at once. You see a blinding white light and hear an immense and godly version of the explorers' song. After the credits, the screen displays a new universe in which hollow, DayGlo planets riddled with holes have formed around stars, and if Solanum was with us, we see a campfire light on one of the new worlds.

After reading about scientific cooperation and performing it indirectly for the entire game, in the finale, we get to see it occur before our eyes. It is the zenith of applied physics. As people gain knowledge, they gain new abilities. As sentient beings' understanding of mechanics has evolved, we've become able to cook, to fly, to make thinking machines, and in Outer Wilds' world, even to teleport or overcome quantum limitations. These advances were achieved through not just surfacing information but sharing it, and as such, the campfire is the most important image to Outer Wilds. It represents one of the earliest and most influential examples of human discovery in physics, an application of that discovery, and the distribution of the involved knowledge.

Mastering fire is often seen as the breakthrough development of prehistoric man, and that ability to cook, light spaces, and stay warm became essential to our dominance over the rest of the animal kingdom. All worldly and technological development since has its heritage in these early revelations, even science as advanced as general relativity and quantum mechanics. Fire literally illuminates, embodying the ability to see what was invisible before, integrating with the symbology of the Eye. It also serves as a cultural totem that people gather around to communicate over and is synonymous with storytelling.

So, when we see the Hearthians, irrepressible explorers, sitting around separate campfires and then uniting around a single one, it's a metaphor for them taking their individual scientific discoveries and combining them. Their lone songs, otherwise lost in the night, harmonise into a collective orchestral, and at that point, the smoke that floated free and wispy from chemical reactions conforms to structure. It's nature guided by the scientists reshaping it hand in hand with each other. Like every one of them has their own instrument, they each bring some knowledge to the scientific table that the others can't. And the concentration of energy that is the campfire gives rise to another compact space of extreme energy density: a universe undergoing a big bang.

Just as understanding combustion let us create the combustion engine and understanding electricity let us create electronics, Outer Wilds proposes that understanding the universe could let us birth a new universe. For the first time, we wouldn't be slaloming around the existing laws of physics to achieve some result; we could write new laws. The way that planets form is a result of the physics of gravity, and the planets forming differently in the second universe tells us there are new protocols of physics. With the right conditions, a new universe could even give rise to new explorers. So, by placing the campfire at the end of the adventure, Mobius Digital aren't just connecting it to the start of the loop. They're drawing a line from intelligent life's first great discovery to their ultimate discovery. In spirit, the cavepeople striking a spark in dry wood are doing the same thing as the astronauts sculpting a new universe.

I am convinced that Outer Wilds is important to games as an art form because its message is inseparable from its medium. A film or a novel can show you a character applying scientific principles, but it's one thing to observe someone else doing it and another thing entirely to do it yourself. Only through a systemic, reactive experience like Outer Wilds can we make a little corner of the cosmos into our own laboratory, to imagine a world outside our current understanding, and to use our raw creativity and smarts to test whether that world exists. And if you keep prodding all the bricks in the universe's wall, just now and then, you'll push through into a reality that previously seemed inconceivable. That is the scientific enlightenment that Outer Wilds so knowingly captures. Thanks for reading.