The’ Awesome Button’ - One press can ruin the game

By ObeyCabbage 14 Comments

Seemingly vast stretches of desert are broken apart with intermittent signs of chaos, attempted escape and desperation. The player and their A.I comrades battle against gales of wind, the tail end of a devastating sandstorm that had previously brought their helicopter crashing down. Upon finally reaching the top of, what appears to be a dune, but is actually a sand covered freeway entrance; the remaining swirls of floating sand disappear to reveal a devastated Dubai. The scene from the elevated platform is eerily beautiful, a teal sky compliments the endless, orange dune covered surface; a film-like visual treatment that developer Yager has adopted to accomplish their intended Hollywood style direction in their yet to be released title Spec Ops: The Line.

Based upon Heart of Darkness and Apocalypse Now, Spec Ops: The Line promises a mature plot within a unique setting. Players assume control of Captain Martin Walker who, accompanied with two other Delta force soldiers, is tasked with investigating the incident following the devastating sandstorm, and rescue a missing army Colonel. Spec Ops: The Line will be the first entry into the franchise that features an accentuation on narrative and plot.

You know the world has gone to shit when someone has gone out of their way to raise the American flag upside down.

While this may seem like the beginning to a review for the game, this information has been gathered from playing the demo alone. It’s necessary to highlight Yager and 2K Games decision to build and emphasise the game’s ‘mature’ narrative and plot, as the demo itself manages to break this structure.

In today’s AAA video game climate, it’s becoming more and more imperative to implement a strong emphasis on visuals to compete against rival games, regardless of other decidedly important aspects of design. This visual ‘flair’ may come in the form of an artistic style choice or specific character actions and animations. Problems arise when the balance between a game’s visual flair and the other aspects of design is not made. As of late, more and more games are experiencing this imbalance, the quality of the other aspects of a game deteriorate in favour of high quality visuals. In the case of Spec Ops: The Line, the decision to implement an “execution” button ruined any opportunity for me to appreciate the narrative; or perhaps more accurately, it was the method in which I was initially encouraged to use this ‘awesome button’.

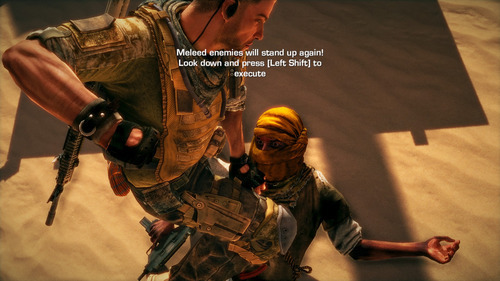

After fighting through waves of enemies through makeshift corridors of abandoned cars, road signs and parts of various buildings, Walker enters a shipment crate, alone ( it seems his A.I squad would prefer not to follow him through). Upon reaching the end of the closed crate, he barges the door open, sending an adversary who was holding it shut sprawling onto the sand. The player is then reminded that they are still in the tutorial section when white text appears on the screen, encouraging them to ‘execute’ this man you have effectively subdued.

Stone faced Walker remains composed as he stares into fearful eyes. All in the name of ‘looking awesome’.

Upon holding the prompted button, Walker enters an animation in which he stomps on his victims chest, followed by a killing blow to the head. By today’s standards of video game violence, this scene is relatively tame, the context however, is where I found the problem. Up until this point in the game, Walker is still operating as a decorated Captain of Delta force, apparently trained and disciplined; and in no circumstance should this enemy be murdered in such a way, other than because ‘it’s a game’ and ‘it tells you to’. In a game that opened with a promising premise and seemingly grounded in reality, it’s disappointing that the illusion should be destroyed so early on, with just one push of a button. Perhaps further into the game, performing this execution move feels justified in context to the narrative; in that case, they should have left this prompt until then.

He’s gonna feel that in the morning. No, wait…

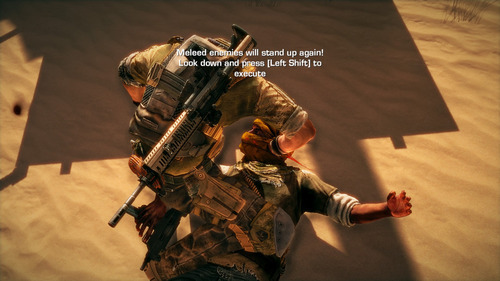

Spec Ops: The Line is by no means the only culprit in sacrificing integrity for visual flair, another recently released game, guilty of conforming to this practice is Max Payne 3. Back in May, Keith Stuart wrote a fantastic article, acknowledging the growing problem of narrative dissonance in video games, arguing that Max Payne is a prime example, with good reason. Overall, the gameplay feels disjointed from the game’s narrative; after Max breezes through waves of scripted enemies through corridors of varying colour and style in a hail of bullets, he returns to his dilapidated apartment to console with a bottle of spirit about his past and present.

Oh, Melancholy!

Joining him along for the ride is the series trademark painkiller pills, interestingly, developer Rockstar has decided to introduce the drug into the game’s narrative, perhaps in an attempt to further support Max Payne’s new realistic direction. However, no explanation is given to why Max has the ability to slow down time, unless this is a side effect to the copious amount of pills he consumes, although I should not have to come up with my own reasons. When all other elements of the franchise had been reworked to fit Rockstar’s grounded, realistic motif, the inclusion of ‘bullet time’ requires a suspension of disbelief that shouldn’t be necessary.

The awesome button in Max Payne 3, what really drives home the disappointing contrast between the gameplay and narrative, is the ability to continue to shoot your target in slow-motion, after they are decidedly deceased. Upon firing a killing shot at the last remaining enemy in the room, players have the ability to continue to shoot bullets into the corpse in a disconcerting fashion, as it falls to the ground. It makes it difficult to relate to, or believe in, Max’s state of mind when he butchers his victims, then drowns his sorrows and bullies himself through internal monologue, only to rinse and repeat.

This is the ‘cleanest’ screen shot I could take. You should see the others…

The light at the end of the tunnel, an example of a well implemented ‘awesome button’, comes from the game that named it so, and I decided to adopt it for this piece. Saints Row the Third is an example of confident integration of gameplay and narrative, creating an outlandish plot, atmosphere and setting completely avoids any need for suspension of disbelief. From the word go, it becomes apparent what Saints Row the Third is, a game; it feels like a game in every sense. The ‘awesome button’ in Saints row is essentially a sprint button, only when the player comes into contact with another object in the game world, amazing things happen. Upon approaching a car, the player launches into the air, and crashes through the windscreen, forcing the previous driver out. Approaching another character in the game with this button held down will result in one of many comical takedown moves; whether its a drop kick to the face, flying crotch-to-the-face, or a leap frog punch, these moves feel as if they are part of the narrative; but I wonder if this is due to its open, sandbox mechanics and the opportunity to create my own narrative.

More of this, please. I think?

While I continue to purchase games in hope that they will adopt a structure similar to Saints Row the Third, I take solace in the fact that another entry into the franchise is in the works.