Note: The following article contains major spoilers for Control.

"I gotta tell you, the life of the mind, there's no roadmap for that territory, and exploring it can be painful".

-Barton Fink, Barton Fink.

About ten to fifteen years ago, the best-selling AAA games contained more tightly scripted setpiece moments: sequences which all players encountered at the same point in the games, and which kept a firm control on the triggering of gameplay and visual events as well as the sightlines to spectacles. By comparison, play in today's big hitters tilts further towards being open and player-directed, which represents an overall improvement. Experiences in games feel more organic, and audiences can better tailor media to their preferences and own their path through entertainment software. When more rigidly prescriptive scenes do emerge in the medium, they draw less attention than they used to, with a greater volume of affection reserved for personal and emergent interactions. There's also going to be less focus on any one level section when each executable contains more raw "content" than it did a decade ago.

But for all the good brought about by developers taking campaigns off the rails, those meticulous setpieces did have a dark ride kitsch that's been somewhat lost. These level sections were not eminently replayable, and their contrivance was a barrier to suspending disbelief. Yet, there is an art to constructing a thrilling scripted sequence in the same sense that there's an art to constructing a theme park attraction, deftly measuring timing and expertly sculpting your props. And with game development having grown a lot in the last ten to fifteen years, studios may even be able to help scripted sequences overcome some of their old foibles. I don't want to go back to every other popular title trying to have its No Russian moment, but in moderation, play that makes us an actor on a set, rather than a person in a natural world, can be welcome.

The Ashtray Maze from 2019's Control was an exception to both the contemporary developer's tendency to forgo rigid setpieces and the modern audience's reduced interest in them. Thoughtfully paced and constantly subverting expectations, The Ashtray Maze formed a shared experience that gamers enthusiastically clustered around. Now that we've had some time to digest it, it's worth returning to The Ashtray Maze to talk about how well it all holds up and where I might get a cool jacket like Jesse Faden.

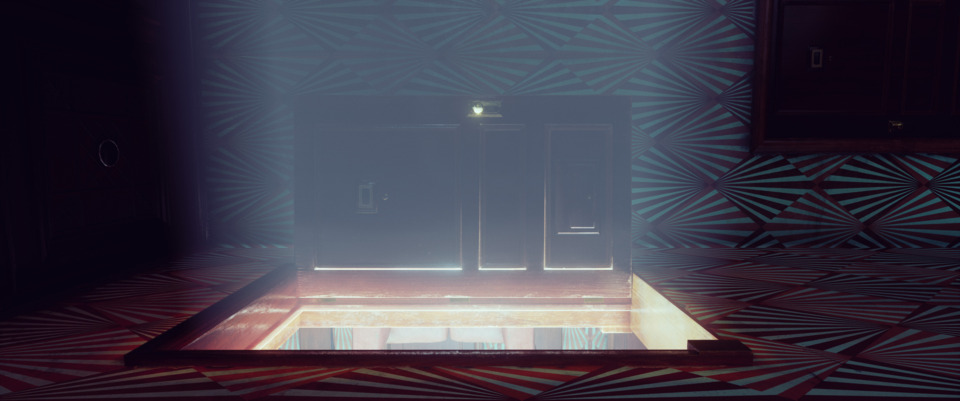

As a static setting, The Ashtray Maze was inspired by the Hotel Earle from the Coen Brothers' 1991 film, Barton Fink. Remedy Entertainment's environment appropriates the Earle's long corridors with regular wooden dividers, uplights, and patterned wallpaper. It even has pairs of formal shoes outside each door, as we saw in the Coens' hotel. "Inspiration" doesn't cover it. Remedy has made the Barton Fink video game right here. And keep in mind, this hotel is situated in The Oldest House, a brutalist research facility. So, The Ashtray Maze, like the Ordinary AWE or the Oceanview Hotel & Casino, is another building uprooted from its original home and concatenated onto a wholly dissimilar structure.

The story mode lets you visit the entrance to the maze long before you can complete it. Beckoning you on through its corridors are these apertures where the walls peel back as though they were made of layers of flat tiles. I could watch them all day. They're like a waterwheel or someone's neck skin flapping in the wind. They remind me of Daniel Rozin's interactive sculptures, the angled slats of which react to viewers' movements. Like a video game, Rozin's art also involves viewers in the piece instead of leaving them on the other side of the fourth wall.

But pass through all The Ashtray Maze's doorways, and you'll end up back at the start of the sector. Before you can venture any deeper, you need to make progress elsewhere in the campaign, but this is a maze, and there's no indication you cannot solve it when you first find it. So, and you're not allowed to laugh at this, I kept running in circles through the area, looking for alternative routes or at least some trigger to unlock them. Again, you're not allowed to laugh at that. It doesn't help that being a looping passage that turns on right angles, the maze resembles P.T.: a game which also has a corridor that, at first, appears to spiral back into itself infinitely, but that transforms when you discover hidden buttons in the environment. I kept looking for those same switches in Remedy's labyrinth.

What Control wants you to do is complete the mission Finnish Tango, at which point Ahti, the House's janitor, gives you a tape player that serves as a backdoor to the true maze. Control's director, Mikael Kasurinen, identifies the janitor's cart outside the zone's entrance as a clue that you need to seek out Ahti to receive your invitation. However, I don't think this piece of scenery communicates anything apart from the enigmatic caretaker having been here, especially not when the game is full of other props that don't convey any information about how to advance.

You eventually traverse this architectural web in the mission Polaris. The level is all false floors and walls that slide into and out of place. Holes open up in what appear to be dead ends, and in one area, security forces phase in, and just as you've realised you're about to enter combat, they disappear behind a barrier, never to be seen again. Nothing stays in one place for long, as the amorphic architecture misleads you into believing in one exit to a room only to pull the rug out from under you. The section has to take place in the game's anterior as the player must be versed in its shooting and platforming mechanics to react with the speed the volatile environment demands. As Kasurinen has said, the layout of the setpiece is simple, but players perceive it as complex because surfaces retreat and advance like a rippling waterbed, and we are frequently asked to remap the path we'll take.

The sequence is able to astonish by capitalising on Control's theme of little being as it first seems. In fact, where the maze works, it's because it's able to pick up and run with Control's concepts better than most other sections of the game. Two of the game's abiding themes are the subjective power of the mind and objects that cause surreal interruptions to our reality. When AAA games try to broach unconventional topics and aesthetics, it's common to see them devise suitable audiovisual representations for them, but struggle to find matching play. So, instead of a game about being a writer or a game that makes you feel like you're inside a Tronesque computer, you just get a shooter but with a writer or a shooter but in Tron.

Control incorporates a lot of ideas from the horror and magical realist fiction website The SCP Foundation. Like the Foundation, Control is full of reality-bending or otherwise bizarre items that have to be contained by a dedicated secret organisation. In both cases, the anomalous entities are described by heavily redacted reports. Remedy's action-adventure goes so far as to include the Foundation's [DATA EXPUNGED]. But The SCP Foundation finds a form that matches its subjects: technical documentation. Its formality, even in the face of human suffering, is chilling. And upfront, each database entry presents the containment measures for the SCP, but no description, creating apprehension. Stories of items and monsters breaking containment, even under a regime of stringent safeguarding, suggest horrific tragedies are not entirely preventable.

Control cannot capture that lightning because it commits the same blunder as plenty of blockbuster games before it. Rather than developing a format that might let us get up close and personal with a wide range of supernatural objects or emulate the phantasms of the psyche, we just get action-adventure mechanics but in a mental landscape. It's why, when Control does reasonably simulate Altered Items/Objects of Power, it's usually the ones that deal with movement:

- The TV that freezes enemies in place.

- The traffic light that you can only walk in front of when it's green.

- The floppy disk that throws objects into you.

- The camera you have to chase.

- The teleporting letters you have to chase.

- The teleporting rubber duck you have to chase.

The game's challenges are largely based in movement mechanics, so while The SCP Foundation can accommodate any type of reality-warping item you can think of, and go to scarcely imaginable new places with it, Control is largely confined to letting you interact with things themed around running or jumping. Another issue arises: The game tries to take special care to match the supernatural properties of objects to their common associations. E.g. The horseshoe that alters luck or the slide projector that opens a window to another universe. However, the need to find challenges that engage the player's levitation, dash, and jump means that sometimes the Altered Items'/OoPs' effects come out of left field. Rubber ducks and envelopes don't have much to do with teleportation. In some cases, the developers can't work out how to activate the subtext of the items at all. The Hand Chair and the Flamingo don't have individualised mechanics; they're just bait to get you into a combat arena.

Yet, in the Polaris mission, a maze gets to be a maze. The Bureau owns an ashtray that can fold the space around it, and the play doesn't so much provide a metaphor for interacting with the object as a literal realisation. And while the ashtray is another OoP grounded in kineticism, Remedy comes at it from a different angle than they do with many of their other extranatural items. While objects like the camera or duck give us a moving goal, The Ashtray Maze has a fixed exit, but moving trails towards it. As in other hazardous areas, bullets and enemies are dynamic entities that we must react to, but in this setpiece, so is every surface. The reaction times necessary to outwit this living level mean that it's also a showcase of the responsiveness of the game's traversal and projectile mechanics, and they pass with flying colours. Control's methods for killing off its apparitions will not be remembered for their longevity, but damn if that combo of psychically pulling some debris towards you and hurling it into one of "The Hiss" isn't snappy.

While the moving parts are the star of the sequence, the still architecture and interior design of this domain also do their part to disorient. The striped wallpaper dazzles like running zebras, and the repeating identical units that make up the thinking hotel are flagrantly unusual. No forest or lake bed would be this uniform; most streets and homes wouldn't either. By the end, huge gulfs of negative space make the chambers very lonely. The Ashtray Maze is a microcosm of Control as a whole. The game challenges the omnipresent belief that we live in a stable and material world. It explores the idea we perceive our surroundings through the lens of our mind, so if our mind is plastic, our universe is, too. Therefore, The Oldest House and, most perceptibly, The Ashtray Maze are, like the mind, ever-changing hallways with infinite doors. The frequent use of symmetry in this space is an afterimage of the dual worlds that Control is obsessed with: our physical reality, on the one hand, and the collective subconscious of associations and stigmas that underlies it, on the other.

Although, the game fails to coalesce a singular vibe around the maze. The diegetic soundtrack for the scene is Take Control, a prog metal song from the Helsinkian Poets of the Fall. In this game, as in Alan Wake, the group plays the fictional band Old Gods of Asgard. It's an odd choice because the Old Gods of Asgard was invented to be a stoner Dad rock outfit, but in its level design and interaction, The Ashtray Maze vies to be taken seriously. The airy verses and thrashing choruses of Take Control are fine in isolation but struggle to find common ground with a Jungian thriller about a woman's childhood trauma. Also, the song's lyrics spell out the background and plot events of Control, and so, end up at odds with the rest of the game's implicit rhetoric. A moment with this much dramatic intensity doesn't call for camp. The same goes when talking about "Dynamite", the novelty pop song that plays when trying to claw back Casper Darling from the nadir of mental oblivion.

The setpiece also bumps its cool factor down a couple of points with a self-congratulatory comment from the protagonist, Jesse, at the end. She heads back into the firebreak, takes out her earbuds and says, "That was awesome". If it's awesome, you don't need to tell the audience. Also, dying in the maze really kills the momentum. This was often the case for these tightly scripted sequences. When pacing is derived from the direction of an episode rather than the inherent loops of play, a reset interferes with it.

The Ashtray Maze is likely shorter than you remember. You can clear it in under ten minutes without much bother, but that an encounter this brief lodged itself in players' memories is evidence of its enrapturing hold. Finding the entrance to the zone can be easier said than done, and I'm not sure that the house musician understood what Remedy was trying to do with it, but there are few to no other areas in video games as alive as The Ashtray Maze. While it would be infeasible to make the whole game out of this sequence for the same reason you're not going to make a whole ring out of diamond, it is a testament to what's capable when you concentrate extraordinary development efforts into one tiny region. Thanks for reading.

Notes

Any time I reference the development of Control, I am pulling from the following source:

- How Control's Most Ambitious Level Was Created | Audio Logs by Gamespot, Mikael Kasurinen (January 5, 2020), YouTube.

Log in to comment