The Whitest Kid No One Knew

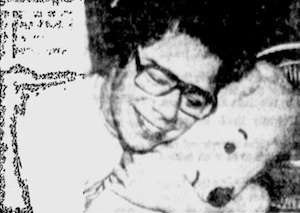

On August 15th, in the Year Of Our Lord 1979, sixteen year old James Dallas Egbert III disappeared from Michigan State University. The casual observer might have assumed that his name was so incredibly white that he was instantly raptured up into an entry-level position at National Public Radio, but such was not the case.

James Egbert's family hired famous private detective William Dear who, upon investigation, learned that James Egbert had been known to play Dungeons & Dragons, a game Dear initially knew nothing about. Dear publicly hypothesized that James Egbert may have become lost in the steam tunnels below Michigan State while under the delusion that he actually was his D&D character, random speculation the media quickly spun into a myth that went on to captivate a horrified public.

James Egbert was found one month later in Morgan City, Louisiana, but the real facts of his disappearance wouldn't emerge for years, while the truth about who James Egbert was has remained obscure to this day, eclipsed by the fantastic urban legend of the kid who went crazy playing Dungeons & Dragons, despite the fact that the true story of James Dallas Egbert III is far more powerful, tragic, and interesting than the myth could ever presume to be.

James Egbert was brilliant. He was repairing Air Force computers at the age of twelve, and was taking a college level computer science course at the age of sixteen when he disappeared.

James Egbert was neurotic. He was severely depressed, and socially inept to the point he, in the words of one Dr. Louise Sause, "was socially redardant, and in some respects could be considered mentally retarded”, a condition that would likely be diagnosed as autism today.

James Egbert was under enormous pressure. His parents had pushed him to excel as soon as his precocious intellect emerged, forcing him to advance at light speed through a system that wasn't designed to accommodate his unique needs. Taking college courses at the age of sixteen would take a toll on someone in perfect mental health. Exposing someone in his mental state to it was dangerous.

James Egbert was taking a lot of drugs. James had a working knowledge of chemistry and access to university laboratories that he leveraged to synthesize a rich variety of narcotics.

Lastly—and most importantly, given the time and place where these events unfolded—James Egbert was gay. (Though he might fall under the broader rubric of LGBTQ+ today, I'll be using the parlance of the time for heuristic convenience.)

We will come back around to the true story of the short, tragic life of James Dallas Egbert III, but for now we must look away if we are to follow the tide of popular culture, which left both the real boy and the true facts of his life behind in favor of another, much more fanciful, much more stupid narrative.

Once the story of youthful imaginings gone horrifically wrong emerged it effectively took on on a life of its own, becoming a sort of narrative Rorschach Test where different people could look at it and see whatever they feared most. Unlike what James Egbert was actually experiencing at the time, these were real delusions, with real consequences for society at large.

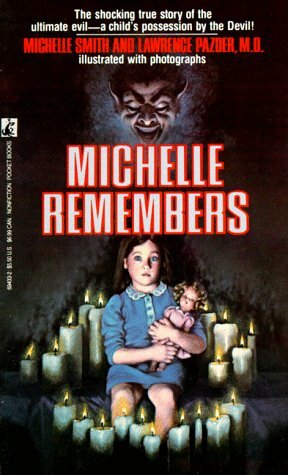

Like the prejudice that actually drove James Egbert underground (not literally) the D&D Mania story was powered by fear, which was in turn powered by ignorance. At the time only a vanishingly small number of Americans had any idea what playing Dungeons & Dragons actually entailed, ignorance compounded by groups of Evangelical Christians freshly politicized by a collective backlash against segregation and second-wave feminism, who were suddenly eager to see Satanist conspiracies everywhere. The Satanic Panic floodgates would be fully opened in 1980 with the publication of the spurious tell-all book Michelle Remembers, a salacious memoir recounting various fantastic and, in retrospect, totally unbelievable tales of ritual satanic abuse exhumed by the titular Michelle via the now thoroughly discredited practice of repressed memory recovery.

Primed to panic, parents were afraid Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson had infiltrated their communities and were building an army of brainwashed Satanist sleeper cells in basements and rec rooms all across bourgeois America—and no one ever went broke indulging the public's irrational fears.

Indeed, some make a tidy profit.

Mazes and Monsters and Madmen and Morons

The author Rona Jaffe wrote her novel inspired by the fake story of James Egbert's madness at blazing speed, driven by the fear that someone else was writing a similar book to capitalize on the D&D Mania gripping the nation at the same time. (She was right.) The result was the alliteratively titled Mazes and Monsters, which came out in 1981. The novel's story hewed closely to the narrative of James Dallas Egbert III's supposed madness as described by the fourth estate, portraying a young man who loses touch with reality and comes to believe he really is his RPG character.

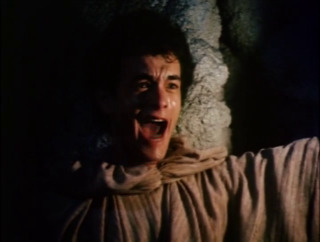

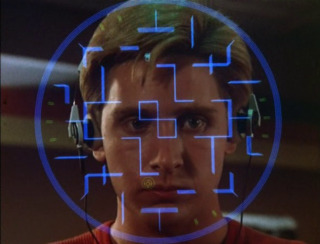

The hysteria regarding tabletop role playing games reached both its apex and its nadir in 1982 when Mazes and Monsters was adapted into a made-for-TV movie featuring a young Tom Hanks as Robbie Wheeling, an innocent high schooler who experiences a complete psychotic break where his real identity is subsumed by Pardue, his fictional character from the titular game. Robbie enters a state of flamboyant lunacy that has him, among other things, slaying a rubber monster called a “Gorvil”, which sounds more like the name of a wacky neighbor on a sitcom than something out of a monster manual.

The movie climaxes with Hanks's friends just barely managing to talk him out of jumping off the roof of one of the World Trade Center towers so he can “Join the great hall.”, claiming “I have spells. I'm going to fly.”

Hanks's restored sanity proves fleeting however, and the movie depicts him spending the remainder of his life trapped in a world of his Maze Controller's creation. It ends with the following somber narration:

“And so... we played the game again... for one last time. It didn't matter that there were no maps... or dice... or monsters. Pardue[Robbie/Tom Hanks] saw the monsters. We did not. We saw nothing but the death of hope. And the loss of our friend. And so we played the game until the sun began to set... and all the monsters were dead.”

It is exactly as stupid as it sounds.

Today Mazes and Monsters exists as a cultural artifact that's only worth watching as a relic of national hysteria and for whatever ironic amusement can be derived from watching a young Tom Hanks humiliate himself. (Turns out it's a lot.) In the present day we no longer have Movies of the Week or Very Special Episodes to help us whinge over the moral turpitude of our young people, and the news cycle moves too quickly for each fleeting moral panic to become a proper cross-media extravaganza.

Now, as we gaze back through the mists of time, it's amazing to see how long a good moral panic could linger in the cultural zeitgeist, and how many variations on the theme could be made by people desperate to exploit it before popular attention wandered off to focus on the latest novel threat to western civilization's youngsters.

That was one of the reasons why I was so captivated when I happened upon The Bishop of Battle segment in the 1983 anthology horror film Nightmares, a story that somehow manages to be both a naked attempt to capitalize on the moral hysteria gripping America in regards to video games and a surprisingly good time capsule of arcade culture at the same time, with a hearty dose of racism thrown in lest you forget it's still a product of Reagan's America.

Some Kind of Fiend

The film Nightmares consists of four different segments that were originally produced for the horror television series Darkroom. The show was deemed too intense by production company Universal, and the four episodes were instead bundled into a horror anthology film for theatrical release. All four of the film's stories are didactic in some way, including the tale of a woman who goes out to buy cigarettes despite reports of a psychotic killer on the loose, a priest who looses his faith and has to contend with a truck driven by Satan, (yes, really) and a father who puts his family in jeopardy by being too cavalier with a rat infestation. The three segments are okay in a thoroughly unremarkable, network TV kind of way, maintaining a staunch mediocrity that makes the exceptional The Bishop of Battle segment stand out even more by comparison.

The Bishop of Battle segment isn't just a short horror film. It's a dramatization of parents's fears that their children were being swallowed whole by the pornographers of violence who were invading their strip malls, laundromats, and youth centers one arcade cabinet at a time.

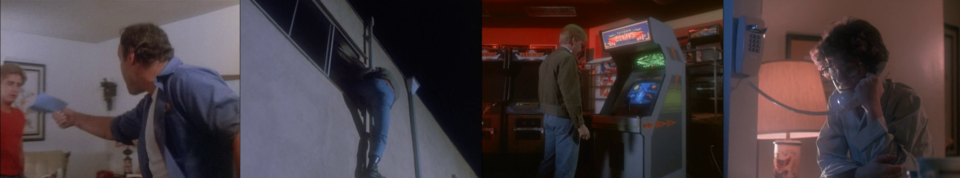

The Bishop of Battle segment opens with Emilio Estevez walking down an L.A. street at midday accompanied by his significantly younger companion and music from L.A. hardcore punk mainstays Fear playing from his cutting edge Panasonic Walkman's tape cassette, which is something you young people may recognize as the tiny clear plastic boxes old people claim to purchase ironically.

Whoever chose the soundtrack in The Bishop of Battle segment had exquisite taste, including music from seminal west coast hardcore punk groups Fear, Black Flag, and Negative Trend. The segment opens with Fear's song 'I Don't Care About You' blasting on Emilio's headphones (Foreshadowing!) while his friend expresses reservations about what they're about to do. Emilio brushes his concerns off, depraved video game junkie that he is.

They enter an arcade, approach the hairnet-sporting cholo gentleman pictured below, and challenge him to a game. Emilio's young friend says "Oh no, J.J. You'll end up losing those ten bucks you got cutting old man Harrison's lawn. " Emilio replies "Shut up, Zock, I don't always loose."

Emilio Estevez's character is named J.J.

His friend is named Zock.

Zock.

Like Sock.

But with a Z.

The gang banger they're challenging knows a sucker when he sees one, and accepts J.J.'s wager: a buck a game, five game minimum.

The writer of the Bishop of Battle segment clearly knew nothing about Hispanic people and their strange Hispanic-speak, (I think it's called Spanish.) and can only flesh out the character of the guy J.J.'s challenging by having him say the word "esse" a lot.

It is impossible to overstate how many times he says the word “esse”. All of the following are direct quotes.

“You wanna play, esse?”

“Okay esse, we'll play.”

“Okay esse, lemmie see if I can cover it, alright?”

“Pleasure taking your money, esse.”

“Be my guest, esse.”

“Don't get nervous, esse.”

“I'm a hard-ass gang banger who finances his glamorous criminal lifestyle by playing video games for money, esse.”

I made up that last one, but my point stands. He's onscreen for five minutes, and he says "esse" six times. That's 1.2 esses a minute!

J.J. looses, and over the protestations of dear Zock he proposes one last game, 20 dollars each, winner take all. His opponent has to clear it with his supervisor, who you know is the guy in charge because he has a cane.

Cane Man approves the match. Unlike the previous games, J.J. puts on his headphones and listens to 'Let's Have A War' by Fear as he plays. He wins handily because, as one young gang member suddenly remembers and tells Cane Man: "That dude's named J.J. Cooney. He's the best, man, best who ever was, you guys are getting hustled." Noble Zock and J.J. manage to snatch up the dough and scamper away from the gang members eager to kill them over twenty dollars.

Having barely escaped with their lives and filthy lucre intact, they proceed take the bus to Fox Hills Mall. As J.J. strides deliberately toward the video game he risked his life and the life of his friend to play, he has a running argument with Zock. (Zock. His name is Zock.) J.J. wants—no, he needs to reach the legendary thirteenth level of The Bishop of Battle game, spoken of in story and song. Gentle Zock protests that there is no such thing as the thirteenth level, but J.J.'s faith is unshakable. There is a thirteenth level he insists, he heard a kid in Jersey got there twice. Goodly Zock insists J.J. hand over his share of the money, but J.J. wants his beloved Zock to come with him, prompting the following exchange

“Why don't you just come in with me, just for two or three games.”

“Yeah, which turns into ten games, which turns into all night.”

J.J. finally gives up and throws gallant Zock's share of the money on the mall floor.

“Go, go all the way to hell for all I care.”

“You know what, J.J.?! You're nuts! That machine's made you into... some kinda fiend!”

This is no mere Pac Man Fever. J.J.'s addicted! He's like a dope fiend, but for video games! Fortunately the movie never goes full Requiem For A Dream, showing J.J. pleasuring degenerate yuppies for fistfuls of quarters, but the implication is there. Indeed, The Bishop of Battle is more fiendish than even faithful Zock imagines, but for now J.J. enters the arcade like a returning hero, earning warm greetings and hearty accolades from all the kids gathered within—one actually physically removes the child that's playing The Bishop of Battle so J.J. can take his proper place at the arcade cabinet.

J.J. is greeted by the Bishop of Battle himself, a green wire-frame model of a human face that resembles a more well-groomed version of Polygon Man. The Bishop of Battle doesn't move its lips as it speaks, but compensates by lazily floating around like a screensaver.

The Bishop of Battle speaks in a stereotypical high-pitched nerd voice, saying

“Greetings Earthling, I am the Bishop of Battle, master of all I survey. I have thirteen progressively harder levels. Try me if you dare.”

J.J.'s dares, and his surprisingly dainty hands grip the controls, which include a knob, several buttons, and a gun.

It's not exactly clear how The Bishop of Battle controls work, but the design is good, hearkening back to a time before there was one singular, dominant controller; a time when each game necessarily came with its own purpose-built design scheme incorporating pedals, wheels, levers, joysticks, guns, trackballs, and even the occasional yoke.

J.J.'s fellow arcade dwellers gather around and a lavishly shot gaming montage set to the song 'Mercenaries' by Negative Trend ensues, featuring The Bishop of Battle's graphics.

The computer graphics in The Bishop of Battle are excellent, accurately capturing the cold neon elegance of early 3D wireframe vector lines. As I watched Emilio play, the fundamental corniness of The Bishop of Battle segment's story fell away, and a warm tide of latent video arcade memories rose up inside me. I remembered the intensity of those days, the cacophony of overlapping digital arcade noise dying away as I zeroed in on a game with absolute zen intensity, the rapture of utter immersion, the dim awareness that I was accruing an audience as I approached the final level.

An outsider might identify J.J.'s expression as that of a tweaking addict, but I know that face all too well, have seen it reflected back at me in the darkness of momentarily blank screens too many times to know it as anything other than the look of focus, of oneness, of transcendence.

Then it's over.

There's the sudden awareness of being unceremoniously dumped back into a body that's covered in sweat; your hands are shaking, your legs are moments away from utter collapse. You're back in the world of flesh, left with an almost postcoital sense of cathartic release. (And shame, depending on how you were raised.)

J.J. dies on the twelfth level, and instead of basking in the afterglow of a game well played he immediately wants to start over, driven by his compulsive lust to reach the thirteenth level. The other kids aren't having it, and file out of GAME-O-RAMA in spite of J.J.'s impassioned pleas for them to stay. Eventually his cajoling deteriorates into abuse and he yells "Go on home! Who needs you talentless clowns anyway! Get outta here!", words that could've sounded genuinely hurtful if they were coming from anyone besides Emilio Estevez, who invests them with all the gravitas of a Borat impersonator declaring “My wife!” for the hundred thousandth time.

As J.J. slouches back to the arcade cabinet to resume his quest for the ever-elusive thirteenth level there's a brief exchange with none other than Moon Unit Zappa herself, who says “Come on J.J., let's go get a pizza, we'll sit and talk like we used to.” J.J. says something that sounds for all the world like “China pal I'm not into that crap anymore.”

Incoherence notwithstanding, Moon Unit Zappa takes J.J.'s utterance as her cue to exit, leaving J.J. to re-engage with The Bishop of Battle for only a moment before the arcade owner closes up shop, kicking J.J. out in spite of the stream of increasingly menacing threats this elicits from the now blatantly tweaking video game junkie.

J.J. grudgingly returns home, where he engages in an apocalyptic fight with his mother and father who, upon seeing his dismal report card, ban him from playing any and all video games until his grades improve. J.J. responds with classic addict behavior: justifying his actions, saying he'll never be in such peak video game condition ever again, trying to bargain with the promise that if he just reaches the 13th level he'll permanently retire from gaming, asking for just a few more days, then just one more day. When his parents refuse to bend he bellows "I hate the both of you!" and retreats to his room with a slammed door. Video games are tearing the Cooney clan apart! There's blood on your hands, Atari!

With 'Rise Above' by Black Flag playing in the background, J.J. climbs out of his window, shimmies down the drainpipe, and scampers off into the night.

J.J. breaks into GAME-O-RAMA with ludicrous ease and resumes playing Bishop of Battle. Meanwhile, cherished Zock calls J.J.'s parents in the middle of the night to report he had a bad dream about J.J., during the course of which the actress playing J.J.'s mother utters the immortal line "Zock, is that you?" J.J.'s parents discover J.J.'s absence, but by then it's too late, he's in the grip of The Bishop of Battle's neon claws.

The game's perspective switches from isometric to first person to signify J.J.'s growing immersion as he blasts his way through wave after wave of four distinct wireframe enemies until he at long last conquers level twelve, which results in a flurry of random but cool looking geometric shapes.

J.J. steps back to exult in his victory, not realizing he's still holding the plastic gun that's come unstuck from the control console. The arcade cabinet implodes, and the true horror begins.

J.J. is enveloped in a pulsing blue light, and it is revealed that the legendary thirteenth level of The Bishop of battle is nothing less than reality itself! The line separating gaming from living is erased as hostile NPCs pour forth from the destroyed cabinet and invade the GAME-O-RAMA for... some reason!

Perhaps it's the result of the Bishop's spite at being bested! Perhaps J.J.'s sick obsession ripped a hole through the fabric of reality! Perhaps it's the most slow and impractical alien invasion of all time! Maybe it's the result a Virtual Boy prototype gone horribly wrong!

- Whatever the reason, the result is virtual violence bursting forth into the physical world. Both the newly freed enemies and the plastic controller gun wielded by a stunned but remarkably adaptable J.J. begin discharging real fake lasers. The action that ensues doesn't exactly match the lofty standards being set by Nightmares's cinematic contemporaries like Star Wars and Indiana Jones, (J.J. has to stand perfectly still every time he fires a shot so the laser beam can be properly animated.) but there's enough bright lights, flashing colors, and wanton destruction of private property to satisfy the casual viewer.

Eventually J.J. flees the GAME-O-RAMA, whose exit somehow leads directly into a parking garage. J.J. inexplicably discards the only functioning laser pistol on Earth and flees up the parking garage, lest he reach the street and actually escape. He reaches a higher level, (Symbolism!) and encounters the Bishop of Battle in person.

The Bishop of Battle's gigantic floating countenance advances toward J.J., who cowers and screams but makes no effort to get away from a head that moves with all the speed of a sloth trudging through molasses.

We switch to the Bishop of Battle's perspective and can only watch in horror as the green vector lines composing his lips envelop a screaming J.J. The camera fades out before we can see precisely what happens, but the implication is that the Bishop of Battle somehow devoured J.J., the video game addiction that has been figuratively consuming J.J. for the whole segment now rendered violently, horribly literal—or it would be if Emilio Estevez writhing on the ground and squealing while primitive computer graphics accost him wasn't hysterically dumb.

The story flashes forward to the next day. J.J.'s parents and the ever-faithful Zock, have been searching for the errant J.J. everywhere except the one place where the game he's is singularly obsessed with is. They finally go to the GAME-O-RAMA arcade, arriving just as it opens so they can behold the destruction wrought by J.J.'s playtime intemperance, though The Bishop of Battle arcade cabinet is mysteriously intact. Our dear Zock approaches the game. What does noble Zock see?

J.J. has been literally absorbed into the game, and is now doomed to be the player's avatar, which would be a fate worse than death for most people, though given J.J.'s obsession this seems like the best thing that could have ever happened to him, a punishment so profoundly ironic it loops back around to being a reward. The real victim in all this is Zock, but that's more due to him having to go through life with the name 'Zock' than any trauma resulting from him seeing his friend become a video game character.

The End. On to the segment where Satan drives an evil truck up out of the ground!

I have, to say the least, mixed feelings about The Bishop of Battle segment contained within the justly forgotten film Nightmares. On the one hand, it's a vivid and surprisingly competent portrayal of a bygone era when gaming sessions were measured out in quarters, people crowded around arcade cabinets like cavemen huddled around fires, and every game was a portal to a new universe that ranged from the awful to the mediocre to the glorious. On the other hand, The Bishop of Battle segment is a hysterical, reactionary dose of clumsy, tone-deaf fearmongering designed to stigmatize an entire entertainment medium. On the other other hand, it stars Emilio Estevez, and I really shouldn't take anything that stars Emilio Estevez seriously that isn't Repo Man.

What's certain is that some degree of craftsmanship went into making the segment. The hardcore punk soundtrack is great, as is the computer animation—which, according to the forever suspect IMDB trivia page on the film Nightmares, proved so costly it nearly bankrupted production.

One of the many ironies couched in this bygone fiasco is now, in the distant future of 2023, the fears of parents three generations prior have finally been realized. Gone is simple, even innocent-seeming Skinner Box video game mechanic of putting a token in a machine for a few minutes of pleasure, now supplanted by predatory pay-to-win gambling schemes designed by psychologists and powered by big data to target the most vulnerable players and exploit them as much as humanly possible, a vicious machine thinly veiled in a candy colored wrapper of cartoonish whimsy. As with so much that defines our current reality, the situation is pre-loaded with maximum absurdity so there is nothing to exaggerate, rendering it beyond parody or satire, exaggeration or hysteria.

As always it is individual lives and the complex, often contradictory forces shaping them that are lost in the public scramble for money, moral authority, and control of the popular narrative. One such discarded life was that of James Dallas Egbert III, whose real story we must return to as this strange, brief yet intense epoch reaches its tragic conclusion.

The Lost Boy

If James Egbert didn't experience a psychotic break playing Dungeons & Dragons, why did he drop out of society? The real answer is that there is no one, single, concrete answer, but rather a confluence of many cruel factors that may have been endurable on their own, but converged to prove insurmountable and unbearable for the sixteen year old James. It's temping to wonder if James Egbert may have been able to live some semblance of a normal life if a few of the factors arrayed against him were removed.

If his autism was properly treated...

If his parents were kinder...

If he wasn't under such intense pressure to excel...

If he wasn't sent to college before he was ready...

If he hadn't been using narcotics...

If he lived in a time when homosexuality was less stigmatized...

If he hadn't been around people who used him...

These possibilities naturally torment us because James Dallas Egbert III remains obscure, not only because his true story was eclipsed by a toxic mix of bad journalism and national hysteria, but because even the true facts we have about what transpired are maddeningly vague.

What really happened was this: On August 15, 1979, James Egbert wrote a suicide note, went into the steam tunnels below Michigan State University, and took an overdose of Quaaludes with the express intent of killing himself. The amount of drugs he took proved insufficient to end his life, and he woke up the next day. He then went went to the house of an older gay man he knew and proceeded to take more drugs.

James Egbert spent the remainder of August in a narcotic-induced haze, bouncing between the homes of multiple older gay men in a stupor of sex and drugs until one of the men sheltering/using him realized James was the same boy whose disappearance had become national news. Desperate to put as much distance between himself and the now famous missing boy as possible, he packed a still thoroughly narcotized James on a bus headed for Chicago, instructing him to take a train to New Orleans once he arrived.

James sobered up en route, arrived in New Orleans, checked into a hotel room, and attempted suicide again, this time by ingesting cyanide. When this second attempt at ending his life failed James left the hotel and lived a vagrant's life on the streets of New Orleans. After a few days James met a man who got him a job working in the oil fields of nearby Morgan City. This same man eventually convinced James to give William Dear, the private detective investigating his disappearance, a call.

William Dear announced that James Egbert was found, but no effort was made to dispel the false rumors. With the real facts of James's disappearance concealed, the story of Role Playing Games driving young people insane was allowed to fester unchecked in the public imagination. Meanwhile, James Egbert was placed in the custody of his uncle, and resumed a semblance of his supposedly normal life.

About one year later James dropped out of school, broke off contact with his parents, and moved in with another older gay man. William Dear, who had remained in contact with Egbert, attempted to convince him to move back in with his parents. James Egbert flatly refused, saying living with them was unbearable.

On August 11, 1980, James attempted suicide for the third time by shooting himself in the head. He was taken to Grandview Hospital and put on life support, but was soon deemed brain dead. On August 18th the headline of a story in the Columbus newspaper The Republic read “Respirator Unplugged, Boy Genius Dies”.

James Dallas Egbert III was seventeen.

The ultimate irony at the heart of all this is Dungeons & Dragons could have helped save James Egbert's life. Not on its own of course, but if James had kept playing it could have given him an opportunity to make real friends, people who wouldn't have used him for drugs and sex, people who would have accepted him for the awkward, queer, neurotic person he was.

Naturally, this is all speculation. Perhaps nothing could have saved James from himself or the world he inhabited. One of the fundamental aspects of tragedies is that they leave unanswerable questions in their wake, condemning survivors to pick up the pieces and attempt to fashion them into something that makes sense, assuming they're willing to expend the mental energy to attempt real understanding.

Now, given the amount of information the average person is bombarded with, processing the tragedies and outrages inundating us every hour of every day is quite literally impossible. Our understanding is no longer limited according to the amount of data we have access to but how much of our narrow mental bandwidth we're willing to allocate to a particular topic. The question is not if we will have mental blind spots, but what we will be blind to.

And, most importantly, who.

The Dankey Kang In Us All (which was also fake)

Recently, when I was listening to the audio book Irrationality: A History of the Dark Side of Reason, my attention was piqued when I heard the author unironically mention something called a Nintendo PlayStation. At the time I couldn't help but marvel at how the book's author, a brilliant professor of history and philosophy who's penned a multitude of books and essays, could get such a simple fact wrong.

I don't think it really matters, the author only mentioned the mythical Nintendo PlayStation on his way to making another, far more important point, rather I bring it up to illustrate how even the most brilliant people among us are completely ignorant of things that, to other people, seem like the most fundamental common sense facts.

I consider myself an intelligant

I consider myself an intellinat

I consider myself an intoogulent

I consider myself a smart person, but to someone who's passionate about Fashion, my inability to distinguish Armani from Gucci would no doubt seem like the very height of ignorance. (I'm assuming the two are somehow distinct; I really have no idea.) It's a gap in my knowledge I have no intention of remedying, because I don't think my ignorance is liable to hurt others or myself; that if I encountered a Fashionista they would at worst think me philistine, not a bigot or a fool.

Yet there are very important topics adjacent to Fashion I likewise know vanishingly little about. How the globalized industry powering it exploits labor, pollutes the earth, and destroys local economies, how it excludes and exploits people who aren't white or young or conventionally attractive, how it perverts the self-image of people the world over. I am vaguely aware of the existence of these problems, but have no idea of their extent, their importance, or their possible remedies. How much can I plead ignorance before mere disinterest crosses the line into callous disregard? If a nationwide crisis involving Fashion emerged would I be capable of understanding it? Should I be angry? Who should I be angry at? Should I tweet about it? Will that just comfort me with the delusion of having actually done something? Do I dare disturb the universe? Do I dare to eat a peach?

Perhaps the best we can do, as the severely limited beings we are, is know what questions not to ask when such an incident arises, questionssuch as

How can I profit from this?

How can this validate my preexisting worldview?

How can this make me feel righteous and good?

Doing so at least allows us to narrow our search for the ever-elusive truth without resorting to generalization, cliché, fear, and naming innocent people Zock.

Fucking Zock.

Most of the information in this piece concerning the real life of James Dallas Egbert III came from the article The Disappearance of James Dallas Egbert III By Shaun Hately for the online magazine Places To Go, People To Be, which can be found here. The responsibility for any and all factual inaccuracies is mine and mine alone.

None other than Ryan Davis himself covered The Bishop of Battle segment for his video series TANG, which explores the checkered history of video game cinema.

Log in to comment