On Walden and Editing

By rorie 33 Comments

I sat down and started writing a big long blog post after happening across this Kickstarter for “The New Walden.” As originally planned, these guys were going to take Walden and edit it to make the language more palatable to modern readers, in part by removing allusions to mythology, changing gendered terms to gender-neutral words, and replacing dated or large words with ones simpler to understand.

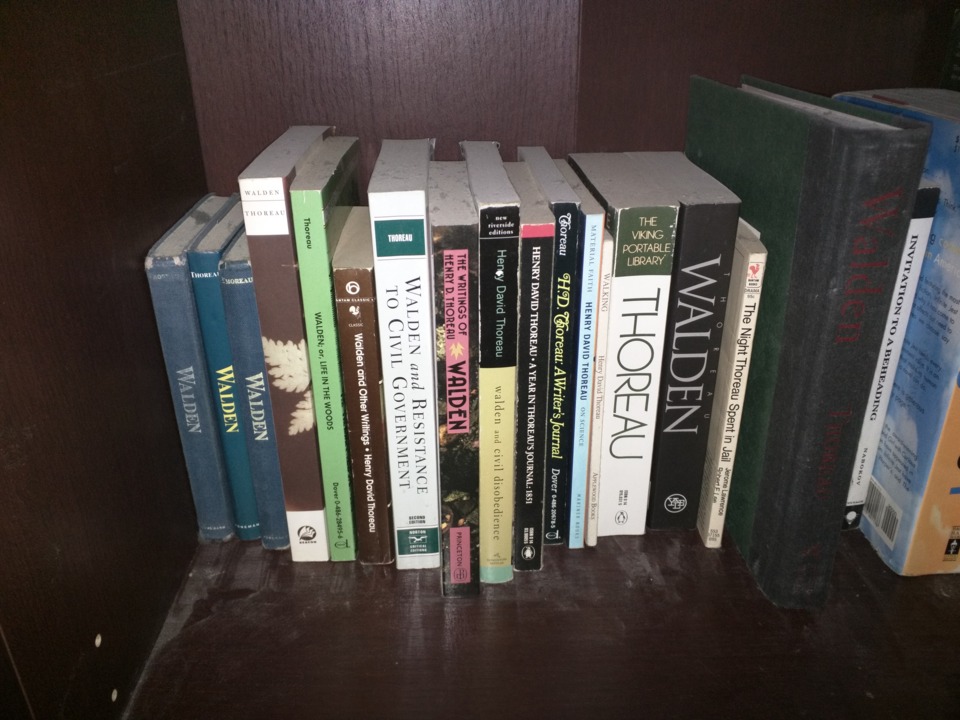

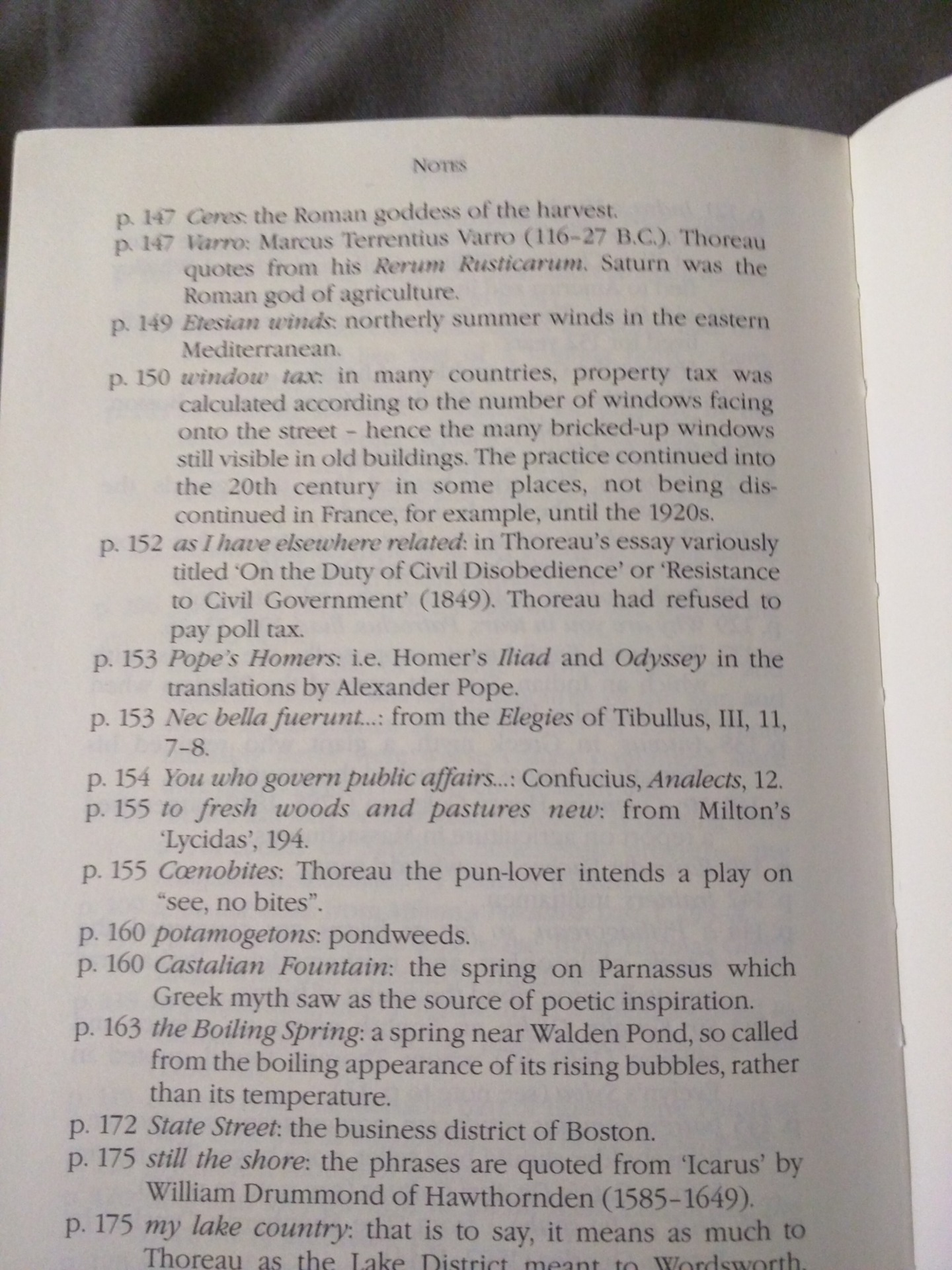

It struck me immediately as a rather bad idea, and I’m guessing that other people felt the same, as the campaign quickly pivoted away from it, instead shifting to just providing same-page annotations for the more difficult parts of the text. Which is fine, so far as things go, but it’s also an odd angle for a $100,000+ Kickstarter. There are plenty of other editions of Walden that already feature annotations and/or footnotes which you can find relatively cheaply (this is one of my favorites, and this one's pretty good if you want something smaller). It feels like that this kind of project would’ve been funded by a traditional publisher had there been a market for it, but what do I know.

Anyway, the Kickstarter didn’t succeed. I take no real pleasure in that; it was obvious that these dudes put a lot of effort into their page and the editing that had already been done. My main concern would be that someone would find this work on a bookshelf somewhere and think that it was somehow authentic or the “real” Walden, which it certainly wouldn’t have been. Walden’s great and everyone should read it, but there’s no reason not to tackle the original work if you’re interested in reading it at all; a vague grasp of context clues will get you past most of the tougher vocabulary (as will one of those, what do you call them, oh yeah, a “dictionary”) and annotations will get you familiar with who Patroclus was if you didn’t get around to watching Troy when it came out.

In typical Rorie fashion, I wrote a couple thousand words and then got distracted by a shiny object, and when the Kickstarter announced their shift away from editing the text, they also eliminated the whole point of writing the damn thing, so here’s the last completely unedited draft of it I had. Nabokov once claimed that releasing drafts was like “sharing one’s sputum,” but, hey: I’m no Nabokov. I can’t claim that this is going to be readable, but I don’t really have the time right now to polish it up. So hey, have a wall of text. I usually wind up starting paragraphs and pushing them off for later when I write, or just abandoning them, so those usually wind up at the bottom of these things. Same with quotes I want to refer to later in the writing process. It's a mess!

begin blog post aqui

I mentioned this briefly and rant-ily on Twitter, but I wanted to discuss this Kickstarter for “The New Walden” a bit. Now, Walden’s a fairly seminal text for me, one of those books that you discover when you’re 16 or 18 and read over and over again, to the point where certain passages are effectively memorized. I first read it in my freshman year of college, and it quickly became something of a vade mecum for me; I kept a small edition of it in my backpack and would read it both at length and when I had a few minutes to spare before a class.

As a bit of context, I was a lonely kid in college. I was scrawny, had a pronounced speech impediment, and didn’t socialize much. I didn’t enjoy having a roommate when I went off to college, so I spent most of my free evening time in empty classrooms (or the library), reading and listening to music. Walden and a few other books (primarily Stephen Mitchell’s translation of Letters to a Young Poet, Richard Zenith’s edition of The Book of Disquiet, Emerson’s Essays, the Maude translations of Tolstoy, and Infinite Jest) were fairly constant companions in those hours, to the point where they almost became surrogates for the real-life friends I didn’t actually have. They were formative: I would certainly be a very different person had I not spent so much time with them.

The paragraph above no doubt sounds like a self-pity parade, but that wasn’t really my intent. I definitely wish that I had spent more time doing the normal college routine of partying and shotgunning beers and finding out how condoms work than I actually wound up experiencing, but even so, I don’t really regret the time I spent alone in those classrooms. Solitude was good for me: I don’t think I would have been a good person to anyone I was friends with or romantically involved with in those years. I needed to figure myself out before I could ask anyone else to deal with me, and one of the ways I did that was reading Walden over and over again.

Walden; or Life In The Woods is, if you haven’t read it, a memoir of a period of Henry David Thoreau’s life that he spent on the shores of a lake in Massachusetts. He built himself a hut on the edge of Walden Pond, on the outskirts of Concord, Mass, and lived there for two years. Ostensibly the book is a paean to the ideal life of self-reliance and solitude, or a manual on living without adhering to the strictures of what’s considered a socially acceptable existence: Thoreau talks at length about the (cheap) costs of building his house, and the economics of the diet that he lives on (which includes a whole lot of beans), and paints everything with the rosy tones of a self-help guru who has figured out the One Weird Trick to living a self-sufficient life off in the forest. He’s a strong independent man who doesn’t need no man, by his reckoning.

The truth of the matter is that Walden Pond was barely two miles from downtown Concord. Thoreau would regularly walk that distance back to his mother’s house for supper and to meet friends while he lived at the pond. Walden paints a picture of a solitary life, consisting of occasional encounters with woodland hunters and wandering migrants, but his tale is pretty far from the extremes of something like To Build A Fire.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/To_Build_a_Fire

So, Thoreau was a bit of a hypocrite. Most high-minded people are, in the end: leaders of Communist nations have often lived in opulence; Tolstoy (despite being the author of The Kreutzer Sonata, which apparently was a call for abstinence even within marriage) allegedly forced himself on his wife fairly often; Ghandi slept with his nieces in the nude after taking a vow of chastity (ostensibly to “test himself,” but, well...yeah); and so on, and so on. Emerson famously stated that “a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds,” and while it’s disappointing to think that great thinkers abide by the adage of “do as I say, not as I do,” that doesn’t necessarily remove the truth in what they spoke. Artists can create art while also being horrible people.

Thoreau, at least, went to the wall for what he personally believed at least once, having been jailed for failure to pay taxes in a protest against the inhumanity that was slavery. (He stayed for all of one night before his family got him released, if I recall correctly.) His embrace of solitude probably also somewhat explained by his failed proposal to a woman (who apparently fancied his brother more), but, all told: better to be a hypocrite by having dinner with your mom a couple nights a week, than, say, railing against homosexuality while sitting in Congress while cheating on your wife with male prostitutes (multiple examples here).

As the last few paragraphs no doubt show, I have a fair talent for running off the rails and taking my time to come to a point. Thoreau did as well. Walden was greatly condensed from his many volumes of journals, but even in their edited form, it still tends to err on the side of florid (if beautiful) prose, with passages running off into extended allegories and references to mythology and classic works of literature. He uses a lot of words to explain ideas that should be simple at times, but if he belabors a point from time to time, that’s only because he believed that point should be thoroughly argued and impressed upon a reader.

Thus I came across this Kickstarter for an “adaptation” of Walden with immediate trepidation.

https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/2001070129/the-new-walden/updates

It looks to be well off the target that it’s aiming for (an almost unimaginable $104,000)

http://www.kicktraq.com/projects/2001070129/the-new-walden/

which I admit makes me somewhat pleased. I bear no real ill feelings towards the creators of the kickstarter, but I have to admit that I find the entire project to be founded on some truly odd assumptions about Thoreau’s writing and the capabilities of modern readers.

Walden has often been said to be more relevant today than when it was originally written; that trope pops up as often in essays about it as the “I didn’t know Idiocracy was supposed to be a documentary” meme does on forums more focused on pop culture. Thoreau railed against the vanity and excesses of his society, and he was doing so well before the Gilded Age or the era of the robber barons or mass child labor or trickle-down economics or whatever other example of capitalism gone mad that you might want to think of. (Although obviously slavery itself was perhaps the purest form of rapacious capitalist evil that the world has seen in the last few centuries, so it’s not like he didn’t have examples at hand to feed his outrage.) It’s no surprise that people would find his words more inspiring as the inequality between rich and poor becomes more extreme.

That doesn’t mean that those words have to be bowdlerized to remain relevant, however, and that seems to be precisely what this Kickstarter aims to achieve. Walden is by no means an entirely easy read, and even with a literacy rate of 90% or above among Massachusetts males in 1840, Thoreau does not seem to have taken any special pains to reduce the complexity of his prose to make it accessible to what I assume to be the majority of the readers of his time. He traveled in the highly literary circles of Concord transcendentalists, and it seems clear that, while he wished to promulgate ideas that he believed applied especially to the poor and downtrodden, he was writing primarily for an audience of highly-educated people who would easily grasp the references he scattered through his text.

The Kickstarter description has a pair of breathtakingly wrongheaded sentences right at the beginning:

“While Walden has always been a challenging book, the evolution of language over the past two centuries has made it harder for modern readers to get into the text. I’m creating a newly annotated, hardcover edition of Walden that I hope will solve this problem.”

This is not a problem. Books can certainly be challenging; that much is undeniable. Meanings can be obfuscated or hidden behind symbolism; words can be obscure or (gasp) require a visit to a dictionary; narrators can be unreliable. These are not problems to be eliminated with editorial sandpaper. Readers of literature should be encouraged to face them, relying on critical or foot-noted editions of a work, rather than resort to translations that make them less complicated and more palatable to a modern ear. They weren’t intended for modern readers, and pretending that they were through the creation of an “adaptation” seems to be frankly insulting.

That might sound like I’m talking from a high horse, and maybe that true. I have a degree in English, and as part of that education, I read a decent chunk of stuff that was all but unintelligible as a 21st century reader. Reading The Canterbury Tales in Middle English was fucking difficult, to be sure, but modern translations lose the poetry of the language even if they retain the essence of the plot.

www.sparknotes.com/nofear/lit/the-canterbury-tales/millers-tale/page_18.html

This is a problem for all adaptation of dated English to modern language (leaving aside the far thornier problems of foreign language translation), but the solution is not to make things easy, necessarily, but to make them easier for an audience that is willing to put an effort in. (As Thoreau asked once, “why level downward to our dullest perception always?”) There is a point where old English is essentially a foreign language and requires outright translation, and The Canterbury Tales is right on the cusp of that border.

Shakespeare is another example, and one that’s probably more familiar to anyone who read Romeo and Juliet or Hamlet in high school. I’m a reader of fairly average intelligence, and I’ll confess to needing a lot of Cliffs Notes to get me through the Shakespeare sections of my high school English classes: not only does he use many words that have long since faded from common usage, but his grammar is also often almost impenetrably dense. Having a modern version of the text side-by-side with the original language is a great help to understanding the raw meaning of the words that Shakespeare was using, but no one would claim that that modern adaptation could ever act as a replacement for the original language. (And if anyone does, run away.) I still don’t understand what iambic pentameter really is after two decades of reading about it, but even a cursory glance at updated versions of the original text make it clear that they remove almost everything that is beautiful about the original words.

I no doubt sound like a snooty elitist when I write all this. I get that texts can be challenging, and it’d be hypocritical of me to slam anyone who wants to make a difficult work easier to understand after a youth spent reading Illustrated Classics and the aforementioned Cliffs Notes.

http://www.greatillustratedclassics.com/

Aides to understanding should be appreciated, but that’s not what this project is: it’s an actual edit of the original work which attempts to supersede Thoreau’s original text, and therefore his original intent. There’ll be no copy of the original text facing the edited pages, as virtually all modern adaptations of Shakespeare feature (unless I’m missing something in the announcement). Instead, a reader coming across this edition of Walden may very well think that they’re facing

But I very firmly believe that Walden is nowhere near as challenging or complex as this project seems to make it out to be for a moderately intelligent reader that has a grasp of what a context clue is, or access to a critical edition with footnotes or annotations that help explain Thoreau’s references

The claim that 162 years ( “two centuries” is a gross and telling overstatement) of time has made Thoreau “harder for modern readers” to grasp seems to me to be

Male literacy was widespread in America by the 1840s, with rates somewhere in the 90% range, but even so,

19th-century (or pre-Hemingway, maybe) prose often can come across as florid or overwrought.

I could sum up (or “adapt”) ee cummings’ poem “since feeling is first” as simply “our love is more about emotion than logic” but that’d be a gross oversimplification. I don’t think that Steel’s edits are on that level, obviously, but there’s just something gross about assuming that someone else’s prose needs editing well after they’re around to approve those edits. Most of Walden came from entries in Thoreau’s journals, and I’m sure that Emerson and his fellow Transcendentalists had plenty of opportunities to edit

Language evolves, obviously, and even this blog post will no doubt be unintelligible given a few hundred years of that evolution. Even the most famous piece of writing in English, Hamlet’s meditation on suicide, is full of “fardels” and “bare bodkins,” and is difficult to grasp without footnotes or margin notes telling you precisely what he means.

“Beautiful imagery notwithstanding, sentences that clock in at 482 characters are pretty hard for modern readers to digest.”

ULTIMATE EYEROLL. Well, deal with it. Seriously: suck it up and read. Sentences do not have to contain one clause. Thoreau might be famous for saying “simplify, simplify,” but he was talking about life, not prose.

http://replygif.net/thumbnail/1418.gif

"[8] I do not suppose that I have attained to obscurity, but I should be proud if no more fatal fault were found with my pages on this score than was found with the Walden ice. Southern customers objected to its blue color, which is the evidence of its purity, as if it were muddy, and preferred the Cambridge ice, which is white, but tastes of weeds. The purity men love is like the mists which envelop the earth, and not like the azure ether beyond."

"A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines. With consistency a great soul has simply nothing to do. He may as well concern himself with his shadow on the wall. Speak what you think now in hard words, and to-morrow speak what to-morrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said to-day. — 'Ah, so you shall be sure to be misunderstood.' — Is it so bad, then, to be misunderstood? Pythagoras was misunderstood, and Socrates, and Jesus, and Luther, and Copernicus, and Galileo, and Newton, and every pure and wise spirit that ever took flesh. To be great is to be misunderstood."