Every AAA game coalesces from the blood, sweat, and late nights of countless developers, but Rock Band 1 was a game that was particularly hard fought for. It wasn't just the output of a single development cycle; it was Harmonix's prize after twelve years of failed experiments and constriction by the industry on which they relied. After falling from the giddy heights of Guitar Hero, Harmonix would make Rock Band the pick with which they'd climb back to the peak of the rhythm game mountain. The game constituted an extreme jump up in scale for a rhythm game developer, one for which there was no precedent.

Talking about scale in the context of rhythm games is always weird. Typically, when we say a game has a large scale, what we mean is that the borders of its world are miles apart or that it's chock full of features and mechanics, but rhythm games rarely allow for spatial exploration, and the format as a whole is not that mechanically dense. The crux of the genre is that you interact with a controller in time to music, the game scores you on your interaction, and there's little going on outside that core play. Scoring systems and hardware can vary, and developers may put out a rhythm title with an exceptionally long tracklist, but no one can tell you the map in the new Ouendan will be three times as large or that they're adding a crafting system to Gitaroo Man. However, Rock Band scales up the rhythm game and does it not by adding a lot of extraneous bells and whistles to any previous experience's core mechanics but by effectively being three overlapping music games on one disc. When we think of it this way, its £180/$170 entry point doesn't seem as extortionate.

That price on the front of the box was always going to be daunting, but Rock Band was doing for the kingdom of music games what action-adventure titles once did for games with direct character control. Instead of being concentrated around the performance of a single task, action-adventure games were about switching between a lot of different mechanical modes, all of which fed into the same nexus. The same idea is enshrined in Rock Band. However, you can spend far more time honing your ability on any one Rock Band instrument than you're likely to spend perfecting your platforming or shooting in an action-adventure. The tasks in Rock Band also feel more distinct than the jobs in most other games because there are three different control mediums for the experience: the guitar, drums, and microphone. Now, we could assume that those input methods are known quantities, especially when titles like Karaoke Revolution and GuitarFreaks existed long before Guitar Hero was in diapers, but these games have more nuance hidden inside than you might think. What's more, there are a lot of small but impactful touch-ups Harmonix made to these formulas, so let's take a closer look at each of these instruments.

Guitar

When you're playing the guitar, your success is proportional to your dexterity. Getting the hang of any rhythm game instrument is about mapping a series of visual cues to physical actions. When you start out with Rock Band's guitar, you will see a green gem come down the track, recognise that you need to press down the green fret button and the strum bar, and do so. With time, you need less and less conscious consideration of where you move your fingers, and you don't have to think about the action of playing a green note any more than you would have to think about how to do up your belt in the morning. It's all pattern recognition and muscle memory, and the same thing applies for the drums, but once you graduate to Hard and Expert difficulty, the game throws you a curveball. Orange notes begin regularly appearing on the note highway, and you must unlearn some of your technique to progress.

When you only have four frets to worry about, you can map a single finger to a single fret. If you see a red note come down the note highway, you know you need to press down your middle finger; if you see a blue, you depress your little finger, etc. But once you have more frets than fingers in play, you can't always keep your digits on the same buttons, and so this simple mapping of frets to fingers goes out the window. Which finger you press down to react to the gems becomes more contextual and learning to adapt to those contexts is one of the most intimidating challenges anyone teaching themselves the Rock Band or Guitar Hero guitar has to overcome. Although, it is true that Rock Band is a little more willing to work orange notes into Medium difficulty songs than Guitar Hero was. There is also a minor challenge in both games in learning to hammer-on and pull-off notes: you have to start thinking about using the fret buttons in or out of conjunction with the strum bar depending on the section you're playing. The changes are also not just on the software end; since Guitar Hero, this peripheral has gotten a makeover.

Rock Band's imitation Fender Stratocaster has an effects switch which allows you to choose the voice you want to colour the overdrive sections of a song with, but a more subtle feature is its redesigned fret buttons. On the Guitar Hero controller, these buttons were tabs which stuck out of the guitar neck, but now the first five frets of the guitar are flat panels which can be pushed down. This means that there's no negative space between them, allowing you to smoothly glide up and down the guitar when you need to change your fingering. Rock Band's designers also thought about how to get players moving their hand greater distances across that fretboard without complicating the play.

Guitar Hero and GuitarFreaks only had players positioning their fingers across the top end of the guitar neck which made input manageable for people who didn't play a real six-string, but it meant that you never got to act out those moments where an instrumentalist slides their hand closer to the base of the guitar. It's a particularly memorable sight if you've spent a lot of time watching musicians drop down to the last few frets to tap out a face-melting solo. What's more, because Guitar Hero virtuosos never moved their hand more than one fret down the guitar at a time, they didn't experience the sensation of frets becoming closer together as you travel south, and so, having to tweak your muscle memory to play with them.

But how do you emulate these high frets without adding so many new buttons that the difficulty becomes staggering, even for experienced players? Harmonix's solution was to add a second set of the existing fret buttons to the bottom of the neck. They still function to hit the green, red, yellow, blue, and orange notes, but when playing through a guitar solo, if you crack a gem using one of these buttons, you don't have to strike the strum bar as you do it, and can tap your way through the solo just like the pros do. As on a real guitar, these higher frets require more precise finger placement but reward it by allowing you to quickly move between them which is a welcome advantage in any frantically fast section. Unlike Harmonix's previous guitar games, Rock Band also gives players bonus points based on how accurately they play a guitar solo, helping lend these frenzies of technical proficiency the same prominence in the play that they have in the audio.

Bass

One problem Guitar Hero had is that the bass didn't feel like its own instrument in the game as much as it did a boring version of the lead guitar. In the real world, basses are distinguished from standard guitars by having fewer strings, and possibly by other physical features, like a longer neck, but because it doesn't make economic sense for Harmonix to release a dedicated bass guitar peripheral, and because they don't simulate strings in their games, bass play was effectively guitar play. When every other part of a band already draws more attention than the bass, the instrument doesn't need a mechanical treatment that makes it fade further into the background.

If you want an element in your game to feel special, whether it's a tool or an enemy, you need to give it an attribute that no comparable element has. Maybe this one sword lights up with fire or this one enemy moves in an unlikely pattern. In this case, Harmonix can't have the bass do anything physically that the other instruments can't do, as they channel it through the guitar controller, so they bring the bass into its own by doing something mechanically unique with it. While all other instruments can only reach a maximum 4x score multiplier, the bass can swell to a whopping 6x. After giving the instrument more scoring power, the designers then inflate the score threshold needed to attain each star with it.

This might sound like giving the player a bigger net only to present them with a larger ball, but because the bass's maximum multiplier is higher than that of any other instrument, it takes more time for the player to rev back up to the full multiplier after dropping a note. While the guitarist may get a more technically complicated note stream to shred through, they don't have to worry as much about consistent play because if the worst should happen and a prompt slips past them, it's only going to be a few bars until they're back at the max multiplier. The bassist may be less likely to play a blistering part than the guitarist, but when there's such a long trek back to their target multiplier, they have to ensure they keep it. They do this by concentrating more on endurance and consistency than the other instrumentalists.

Drums

Even more than the bassist, the drummer has to bind themselves to the rhythm of a track. An essential tactile difference between these instruments is that while you interact with the guitar or bass directly, you must hit notes on the drums through the medium of the sticks. Another thick line of separation is that the drums do not require the fine motor control of the guitar or bass, but instead, ask for big, sweeping motions. This makes them sound a lot easier to operate until you realise they require you to coordinate not just the movement of both of your arms, but also one of your legs, as you have to hit the pedal. In a similar way that incorporating that orange fret provides a whole new frontier of difficulty for the guitarist, one of the tallest hurdles that rookie drummers must overcome is learning to move their leg to a different rhythm than their arms. Hitting the kick drum is straightforward enough when you need to do it at end of a measure, but it's a little harder when you play it in the middle of a bar, and harder still when it's played off-beat or when you have to alternate between the bass drum and the others quickly.

The drums were the first of the instruments that Harmonix began work on; the studio gave themselves more time on this peripheral than any of the others as they'd never developed a drum-based game before. They took a trick from Konami's DrumMania by tilting the drums further towards the player than a real kit does, making striking them feel more natural. However, for the designers, the kick drum posed a puzzle. One of the ways that rhythm games make it feel natural to translate on-screen prompts into manual inputs is to have the note streams on the monitor line up with the buttons of your peripheral. With the drums, for example, the note highway is set up so that red notes appear in the leftmost column, to the right of those are yellow, then blue, then green, and the drums themselves are laid out so that the leftmost drum is red, then yellow, then blue, then green. It makes it intuitive to tell how you're meant to move in the space around you to hit the gems. But if this is the scheme we're using then how do we crib a bass drum into the UI?

In the past, introducing a new note always meant inserting another lane for it on the note highway, but if you do this with the pedal, you create confusion about the layout of the drumkit. Imagine that we put the kick note lane in the centre of the highway, between the channels for the yellow and blue pads, roughly what DrumMania did. The player could easily be tapping the yellow drum, see a gem come down the highway to the right of the yellow road and understandably go to beat the drum to the right of the yellow: the blue, only to miss. That's not a system in tune with player psychology, particularly because users often have to react to prompts on the screen within a split second. The brains at Harmonix found a solution by making the cue for the kick an orange line which sits underneath the other notes. As it's not a gem, it won't be mistaken for a drum that the player has to hit with the stick and its position beneath the other prompts signals that the player needs to interact with something below the top section of the kit, i.e. The pedal.

Another original invention for Rock Band was the drum fill. When the drummer has enough energy to activate their temporary points-doubling power, overdrive, a freeform section will appear at a fixed point in the song. Here, they must play an original drum part and then hit a green gem at the end of it to kick on their overdrive. It rarely works out perfectly because there's often a delay between hitting your pad and hearing it sound through the speakers. It's problematic when trying to match the beat of a track and comprises a latency issue. It could hypothetically be solved by properly calibrating the game to ensure there's no gap between manual input and audio output, but even using the auto-calibrate features in the later Rock Bands, I've always found the sound lagged behind my drumming. This is not a problem during scripted play as the game otherwise doesn't play notes based on when you hit the input, but checks if you were in the rough window of the note sliding over the goal line and continues to play sound on-time until it detects a miss. During the drum fills, however, the game can't know what on-time looks like because you're improvising something that no one has played before. Still, creating drum fills which suit a song is its own new skill, and in this mechanic, there's a glimmer of the early days of Harmonix when the company was all about letting players create new music as opposed to playing along with existing tracks.

The drums require the most room and assembly of any of the instruments, but they're the closest to audibly replicating their real-world cousins. As hitting the drum produces real noise, it is in its own small way, an actual percussion instrument. Because the frame of the drum kit places two pipes below the yellow and blue drums, you even find that the inner drums have a unique sound quality compared to the outer drums.

Vocals

The vocals are the black sheep of the Rock Band family for a couple of reasons: One, the singing doesn't provide an emulation of a real-world musical task; it is the task. If you're singing in Rock Band, Lips, or SingStar, then you're singing. Two, the vocals aren't an instrument. Or if you want to get really weird about it, you are the instrument. Because the vocals do not rely on an external instrument for input, the designers can't use the same visual interface for the vocals that they would for the other modes of play. When singing, you will see a scrolling area of the screen which displays input prompts, but unlike with the UI of the guitar, bass, and drums, it moves across the x-axis rather than the z-axis, and it doesn't use the gem system. The designers built the gem system around the concept that you will have to hit a specific button at a particular time; it can't apply here because there are no buttons. It's relatively straightforward to develop a prompting system for the guitar where you can build both the guitar and the software it interfaces with, using colour coding and a small range of inputs, but the human body wasn't designed for compatibility with a music game. Our vocal cords don't have a colour guide or a restricted palette of actions; the mechanical process that we use to sing a note is complex and hidden from us.

Singing video games could try to tell us what note we need to match in each section (e.g. F# or D) but the majority of people can't match a text representation of a note to a sound, and feeding the user this information in real-time would make play prohibitively complex. An approachable interface for singing needs to communicate the melody in a language we all understand, and while we're not all fluent in formal musical notation, we do comprehend the general concepts of pitch and some notes being higher or lower than others. So that's what karaoke game interfaces rely on, generally showing you how high or low you need to hit a lyric, especially in relation to other lyrics. This is also why the vocals GUI uses the y-axis to denote the type of note to input while the instrumental UIs do it across the x-axis. The guitar, bass, and drum interfaces are referring to objects that exist from left to right in 3D space, so the notes on the screen can be laid out left to right. When singing, there's no spatial input for the UI to be matched against, but the designers can and do exploit the fact that we use the same language to describe height that we do pitch. "High" notes appear higher up on the interface, even if we're using two different definitions of "high" there. The same applies to low notes. Of course, this is a bit of a vague guide so you do need to know the shape of the songs going in, which is one reason why Harmonix picked tracks for Rock Band that they thought people would greet as old friends.

Harmonix borrowed the vocal interface from their earlier title Karaoke Revolution, and while SingStar may be the most famous name in microphone gaming, Karaoke Revolution always had the more sensible presentation of the music. SingStar displays its notes statically and has a cursor move from left to right across them as the song plays. When the cursor reaches the right side of the screen, a new frame of lyrics appears, and the pointer starts over from the left side. This has the potential to throw you off because once you're at the end of one vocal phrase, you can't see the next one coming. You can miss a note for no other reason than the screens advancing quickly and you not being ready for the first word in the next section. Instead of having the lyrics be static and the pointer scroll across the screen, Karaoke Revolution and Rock Band have the pointer remain static, and the words scroll. Under this system, the start of the next lyrical phrase is always visible, even at the end of the current one.

It is also necessary that songs are chopped up into phrases; it's part of maintaining a fair scoring scheme. While missing a note on any of the instruments will cause your combo to break, asking the player not to skip any jot of the vocals would be a much taller order. Again, the notation is far vaguer, and on expert vocals, you're basically replicating the song as a real performer would. Instrumentalists are not held to that standard. So, instead of tracking whether you hit every single microsecond of the melody correctly, Rock Band divides songs into phrases, and measures how much of each phrase you hit. As long as you sing enough of each frame correctly, you retain your combo.

There are other splits between the singing and instrumental play: Firstly, the difficulty curve for the vocals consists of performing one task with steadily increasing specificity, whereas the instruments often ask you to learn some new task at a point like changing fingering on the guitar or incorporating the kick drum. Secondly, while moving from Medium to Hard or Hard to Expert on an instrument means more complex note charts, on vocals, the notes are more or less the same, but as you clamber up the difficulty ladder, the range in which the game considers you to be reaching a note narrows. Thirdly, the vocals are the only territory of the play where accuracy involves more than a simple dichotomy of hitting or missing a note. On the vocals, if you skirt a note, it will contribute a modest amount to the combo meter, but the closer you can get to singing it dead-on, the faster that circle fills. This is the play's acknowledgement that while the instruments use an array of distinct buttons that are all either "on" or "off" at any time, vocalising happens on a spectrum. It also recognises that because that spectrum is so granular, it's not reasonable to demand that players on lower difficulties always hit the desired input with pinpoint accuracy.

To ensure that we can always stretch to a note, Rock Band clings to an established feature of the karaoke genre: letting us sing in any octave. Rhythm games generally work because they have standardised controllers, but the human voice isn't standardised; we're all sonically unique and can't guarantee that we can match the range of voice the original singer used. Imagine that you have a piano in front of you and that your finger is on middle C. Now imagine moving up to the next C on the keyboard. The space from that first C to that second C or between any two notes of the same type is an octave. Those two Cs are still Cs, just higher or lower than each other. All of us have a limited range of octaves we can sing in, and so, the developers of these games measure whether we're hitting the original note, not the original octave. Whether you're a soprano or a baritone, you can still warble along to The Outlaws' Green Grass and High Tides. Although, this does also facilitate a behaviour in a lot of video game singers that you wouldn't get in the real world. Sometimes, instead of sliding their pitch up and down within an octave, players rapidly flip between octaves as they find it easier to sing the higher notes in a different octave than the lower ones. This alternating between a high and low voice tends to sound bizarre and inorganic, but the system still rewards it.

While Rock Band develops its instrumental systems far beyond that of previous rhythm games, it doesn't push the boat out as far with the vocals. However, there was a tidal wave of singing games pre-Rock Band to which there was no equivalent for the guitar or drums. By 2007, there had been far more opportunity for the industry to find out what the right choices were for vocal gameplay and Harmonix didn't have to do much development of the genre to bring it up to speed. The two new ideas they do introduce in Rock Band are "talking parts" where the game scores you not on pitch, but annunciation, and percussive parts which you play either by hitting a face button or tapping the microphone. The former mechanic lets you work through spoken lyrics with your personal style while the latter gives the vocalist something to do while instrumental sections of the song go by, although both were prone to go numb to player inputs.

____

Those are the mechanics specific to each peripheral, but to get a full picture of Rock Band, we also need to think about the mechanics that are universal across the instruments. Let's return to that concept of consistent play. When we listen to someone play music, we want not just to hear them hit every second or every fourth note; we want to receive a whole run of notes in a row. If someone can't play consistently, they can't play music, so, most rhythm games, including Rock Band, reward users for reliable play rather than random spurts of accuracy. Of course, when trying to draw a skill out of your audience, it's good practice to test for that skill using multiple different mechanics. This can help you get a clearer read and give your audience a more rich and varied experience which is why Rock Band checks for consistency using three different mechanics common to rhythm games.

There's the crowd meter which fills as you raise your score and drains as you miss notes. If the meter hits 0%, you fail the song. You'll also notice, however, that it empties on a miss faster than it fills on a hit. This means that it's not enough for you to hit 50% of the notes, you have to be on-point for the good majority of them or you're going to get booed off. This mechanic also plies you with an auditory reward in addition to a mechanical one. In select tracks, if you can keep that meter filled to the top, the crowd will start singing along to the song. It's a feature that Rock Band project lead Greg LoPiccolo thinks was devised by the game's audio director Eric Brosius. It allows the game to embody the atmosphere of playing to a crowd better than Guitar Hero ever did.

The combo system is the most stringent measure of consistency in the game and causes your mistakes to count for more by creating a ripple effect from them. If the percentage of notes you hit was the only factor in scoring, you could get away with a lot of blunders, but the combo mechanic makes it so that when you miss a note, the next several notes that you play will yield fewer points. It's an ingenious technique rhythm games use to weight score strongly for accuracy, and it's one reason why you can play two different runs of a song, hitting 99% of notes in each, and those two attempts can produce scores tens of thousands of points apart. The combo system ties into the crowd meter as it's scoring more points which raises the crowd meter, meaning that keeping your combo is essential for soaring out of the red zone.

The combo meter then stacks with the overdrive system. Songs contain sections where, if the player hits every note in a row, they will receive some "energy". Once the player's energy meter is half full, they can active overdrive to double their multiplier for a limited time. A mediocre player might be able to hit an 8x multiplier now and then or be able to pick up a modicum of energy, but only someone who really has the play down will be able to do both, bringing them up to a frequent 8x multiplier (or 12x on the bass). At least on the vocals and guitar, the overdrive mechanic is also a betting system in disguise and one that rewards the player for awareness of their own abilities, and knowledge of the song.

Optimally, the player should activate overdrive in a section where they know they won't drop notes, so, they have to be aware of when the intensity of a song increases and whether they can match that intensity at that point. If you think you're liable to skip a lot of notes in that upcoming chorus, maybe that's not where you want to double your multiplier. On the other hand, if you know that you can nail it and that that section of the track is where you'll get the best points/time ratio, that's exactly where you want to activate overdrive. Then there are a lot of grey areas in which you can't be sure that you'll keep your multiplier if you activate then and there, but you might want to risk it anyway. There is an additional challenge for the guitarist and bassist in working out the opportune moment to activate overdrive as they must tilt the guitar upwards to do so, and remaining accurate while swinging your controller around is easier said than done.

But just because you're consistent doesn't mean that you should expect Rock Band to be in return. See, you set your difficulty level when playing a track (Easy, Medium, Hard, or Expert), but songs also have their own difficulty rating (Warmup, Apprentice, Solid, Moderate, Challenging, Nightmare, or Impossible). Ostensibly, the difficulty of the play is a combination of the difficulty level you've chosen and the difficulty rating of the song, but the labels on the tracks are not particularly accurate indicators of whether they'll make you break a sweat or not. For example, on the guitar, Electric Version is a Moderate difficulty song that I am incapable of five-starring, but Cherub Rock is a Nightmare difficulty song that I can gold star with no trouble.[1] The spotty difficulty identification continues all the way through the Rock Band series, and while it's irritating for everyone involved, it makes life particularly hard for anyone just learning the instruments. They have to use trial and error approaches to find what pieces they can play because the game doesn't willingly give up that information.

I'm unconvinced that Harmonix could provide wholly transparent difficulty ratings, even if they want to. What a player finds tricky is going to be subjective. One guitarist might think that the hardest part is playing patterns that wind and curve across the highway; another might have more trouble with rapid strumming. Some songs are also much harder on certain difficulties than others, and some tracks have easy sections and more trifling sections. Those last two elements wouldn't come into play in another game where the designer would have total control over the challenge within a level, but despite being the development studio, Harmonix only has so much say over the difficulty.

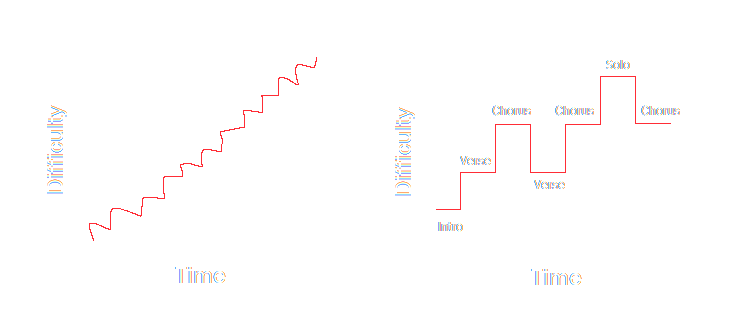

The basis of these levels is not content that was designed by a developer to be fair to the player; it's music that artists wrote to sound emotionally resonant. Many songs don't have that steady curve of difficulty that level design relies on; they have choruses that might be more intense than verses or instrumental solos where the difficulty quickly spikes. Instead of leaving behind easier sections of the level to venture into harder territory, many songs come back to those easier patterns over and over because most popular music contains a lot of refrains. But if you can find your groove, the game remains compelling because it is constantly feeding you inputs you have to pay attention to. During play, there's no downtime, and when the note highway becomes particularly frantic, you can enter a mode where your subconscious does most of the work decoding those patterns and moving your hands or legs into the correct positions.

While we have, so far, only discussed playing the game from an individual standpoint, we can't let that be the sole perspective from which we view this experience. When played single-player, Rock Band may be a singing game or a drumming game or a guitar game, but it's designed for multiplayer and having multiple performers in one room is an experience unto itself. Games always have a different atmosphere when played with other people in the room, but the physical reality is usually a few people sitting around with gamepads in their hands. In Rock Band, the physical instruments, the movements they have your band making, and the noise of operating them all give the whole experience a powerful tangibility. The rock band isn't just something that exists on the screen in front of you; they're in your living room with you. There's no other experience in interactive entertainment comparable to being a guitarist timing your strums to the "taps" of the drummer next to you or seeing every player hit the "Yeah!" portion of Won't Get Fooled Again simultaneously. There is, however, more to playing with a band than just performing the same songs in the same space.

When Harmonix first managed to get a prototype of Rock Band with all its instruments up and running, they discovered that without mechanical ties between the musical ensemble, it didn't feel to them like the players were working in concert. In response, the studio set out to develop features to bring users together. At its most basic level, the game makes the band inter-reliant on each other using the crowd meter. When jamming out in the multiplayer, the total amount of juice in that meter is an average of all player contributions, but each band member also has a marker which will move up or down that pole based on their sole performance. If anyone falls to the bottom, they will temporarily drop out of the session, and as this title is so audio-driven, the absence of the drums or bass in the mix is palpable. However, if a player activates overdrive when one of their teammates is out of play, that teammate will be recuperated. It's the same idea as reviving a downed teammate in an MMO or battle royale game and comes with the same feelings of reliance on others throughout the session and relief when you're saved. It's a beautifully weird proof of how you can adapt a mechanic to your genre, even when it seems like it doesn't belong there. Although, rescuing teammates isn't something would happen in a real band.

A more realistic touch is the big rock ending, a mechanic that LoPiccolo wanted to include in Guitar Hero, even when the stars never aligned so that he could. The idea is this: Some songs end with a chance to thrash away on your instruments like an animal and all those hits feed into a points bounty. It's the cathartic, uninhibited thing you want to do with the peripherals from the moment you unbox them, but no game rewarded it until the big rock ending came along. Here's the rub though: You can only bank the points from your big rock ending if the whole band hits a short sequence of notes after that spurt of random input. If anyone misses their mark, no one gets any points, so, you need teammates you can trust to collect that prize. There's also the unison bonus, a dose of energy that fills 50% of all players' overdrive meters if everyone in the band hits every note in a unison section.

Lastly, players in a group are encouraged to co-operate because they have to activate overdrive with timing that considers how their multipliers will modify each other. You see, if you activate your overdrive in the multiplayer, then it doesn't just double your score, it doubles the whole band's, and anyone can stack their overdrive on top of yours. If two players activate it at the same time, everyone gets a 4x score boost, for three players it's 6x, and for four it's 8x. Keep in mind, that's not just multiplying the amount you can mine from each note; it's augmenting your combo multiplier. So, if you are up to a 4x multiplier on your instrument and then three people activate overdrive, that's 8x4, leading to a total 32x bonus on all the notes you hit in that period.

With that kind of advantage riding on synchronised activation of overdrive, you can't afford to pass it up, but getting all players to kick on the overdrive at the same time is a more taxing exercise than it sounds. While Guitar Hero represented energy notes as star-shaped markers on the highway that retain their lane's colour, Rock Band keeps its energy notes the same shape but has them glow white. It increases their visibility but nullifies the colour coding system; you have to be able to quickly identify which inputs you need to use based on position alone so not everyone manages to bottle the energy they're owed every time. Even more vexing is that, while the more players you have, the higher your potential score, it's also the case that the more players you have, the harder it is to coordinate everyone.

Even if you and your band are a well-oiled machine, you have to remember that every instrument has limitations as to when and how you can activate overdrive. The method of activation is, in each case, representative of the role each player would take in a real band. A real drummer has to follow the rhythm of a song, and this is represented in the mechanics by the person on drums having to wait for a fixed section before they can utilise overdrive. The guitar and bass, being instruments more suited to showboating stage antics can surge into overdrive at any time, but if you want to stack the multiplier optimally, then just like a real rock star, you'll follow the timing set out by the drummer. You must also take caution not to spark off your overdrive right before a section of the song where the guitar or bass go silent. Note that this is a trap that the drummer doesn't have to worry about falling into; guitarists/bassists get more flexibility in when they can activate, but they also run more risk. The vocalist, meanwhile, can launch overdrive during cordoned-off sections of their track, but they receive less energy than the other players and so really have to pick their big moments. Often, they can't activate in time with the instrumentalists, and this helps illustrate the divide between being a singer and being someone holding an instrument.

Keep in mind that when lining up overdrive, you don't just have to account for different band members getting the chance to activate at different times, you also have to take into account that the game doesn't give all players energy phrases at the same time and that some teammates may have missed their energy phrases. Plus, a fitting spot to leap into overdrive for you is a slow or silent moment for someone on another instrument. 100%ing a song is most of the battle, but once you've done that, improving your position on the leaderboard comes down to this synchronisation and control of overdrive, and it's an art in itself.

Speaking of art, you may also notice that Rock Band's aesthetic top layer is coming from a very different school of design than Guitar Hero's. Harmonix's original guitar game burst onto the scene coated in the occult and industrial, swinging heavy metal chains around its head, but through and through, Rock Band's fashion sense is more mature and more abstract. Designer Rob Kay explains that the guiding question when developing the game, including its art, was "is it authentic?". By changing out the colourful buttons on the guitar neck for more functional panels and modelling the controller around the dignified Fender Stratocaster, Harmonix made sure this hunk of circuits and plastic looked more like an instrument and less like a toy than ever, and the other peripherals followed suit, as did the in-game graphics. The characters on stage are no longer larger-than-life headbangers like Axel Steel and Casey Lynch; they are less caricatured. The starpower and rock meter mechanics which implied some heavy metal mysticism in their names are brought down to earth with new tags like "energy" and "crowd meter". Lastly, the UI looks less like metal album art and more tasteful. There are no more pentagrams on the note highway, lightning bolts when you gain starpower, or plumes of fire when you score a note. The play area is a simple black conveyor belt with coloured glass-like objects moving down it.

Guitar Hero's style conveyed attitude, but it also frequently led to aesthetic interference. The satanic scrawls on the fretboard and the UI that looked like it was thrown together in the back of a van were great for metal and sometimes also classic rock, but there are so many genres it would clash with, including pop rock, most alt-rock, most prog, and anything outside of the rock genre. Rock Band and other rhythm games that use an abstract interface do it to avoid that discordance. The UI doesn't assume anything about the style of the music and lets the tone and imagery of the tracks speak for themselves. This was particularly important for Harmonix when building Rock Band because more than any game they'd developed up to this point, this one was intended to be a content platform as much as a packaged experience. Stores on games consoles already sold songs for major rhythm games, but previous developers didn't have the vision for what rhythm game DLC could be that the Rock Band crew had.

Harmonix saw that no one who bought a real instrument was pinned down to learning only a select set of songs and that nobody bought a stereo or personal music device expecting the company who made it to tell them which fifty tracks they could listen to on it. People build custom collections of music, and they carry with them between equipment. Additionally, the idea of compiling the licensed soundtrack that will please all players is conceptually broken. There are as many different tastes in music as there are people, and so, for maximum audience satisfaction, you shouldn't impose a soundtrack on the users, you should let them construct their soundtrack. You must do this not just by offering a few track packs, but by releasing a library of music diverse enough to respect the varied taste in music that audiences have. Having new tracks to keep discovering is also helpful in a game where you're honing a skill by playing a lot of music; it keeps you from having to select the same tired songs repeatedly.

Harmonix released new tracks on a weekly basis, giving players a reason to keep coming back and simulating new record days. At the time of writing, they've released over 3,000 songs. Given the sheer volume of content and the passionate applause this DLC system has received, I don't think it's hyperbole to say that Harmonix was running one of the most successful games-as-a-service ventures to date and that they were doing it long before the wider industry picked up on the concept. If it weren't for Rock Band, we'd have a much less ambitious idea of how many meaningful extras you can offer alongside a game. It was also revolutionary at the time that your DLC would transfer between games.

Because the DLC was such a substantial part of Rock Band for so many players, we can't discuss the on-disc songs in the title with the same implications we'd talk about the licensed music of another game. It's worth commenting on the on-disc numbers as they're part of a shared musical experience that everyone who bought Rock Band underwent, but unlike with most other games, we cannot refer to the songs pressed into Rock Band's discs as "the Rock Band soundtrack". Every player had a soundtrack of their own. However, if we are going to comment on the on-disc music, we can see that in comparison to the tracks on Guitar Hero I and II, the songs that shipped with Rock Band get further away from the long-accepted rock canon, get a little more contemporary, and play more with genre. You have your Bon Jovi and your Kiss, but Harmonix's previous guitar game would never have leaned so hard into alternative bands like The Yeah Yeah Yeahs, R.E.M., Hole, or The Smashing Pumpkins. It's a choice that within itself keeps the game from feeling like a supermarket-grade rock compilation album while still staying true to the vision of Rock Band. However, it also hints at the dizzying combination of bands and styles that players can explore via the online store.

What's impressive about Rock Band from a design perspective is that it takes all these diverse elements and mashes them together without them ever seeming dissonant. Designers creating asymmetric co-op games are often hesitant to make player roles too different from each other or to add too many classes to the system. Doing so can mean that while your players each get an experience that feels like theirs, the paths of the play don't meet in the middle as they should. But in Rock Band, the vocals, the guitar, and the drums all feel like games unto themselves and yet when played alongside each other match like pieces of a jigsaw. That's the mark of masterful design. The keyword with Rock Band is "modularity"; whether it's configuring your band setup or your soundtrack, Rock Band is not interested in dictating what you play, it metamorphises into what you want it to be. Thanks for reading.

Sources

The Harmonix Interview: Greg LoPiccolo by Harmonix Music Systems (Jan 2, 2012), YouTube.

10th Anniversary Classic Postmortem: Harmonix's Rock Band by Rob Kay (November 20, 2017), Gamasutra.

All other sources are linked at relevant points in the article.

Notes

1. Gold stars are a hidden score rating above five stars that players can only attain on expert difficulty.

Log in to comment