The Anti-walking Simulator

Sometimes, constraints are the greatest boon to creativity that there can be. Money, technology, time, and all of the most intelligent minds in the world put together in a pot might come out the other side with, to continue to cooking metaphor, an inedible slab of actual shit. How does it happen? Who can say. The possibility of being able to do everything might make it actually impossible to do anything. Look at Star Citizen and its rapidly ballooning pool of money and constant delays, or at Call of Duty: Black Ops: Cold War, where some of the greatest rendering tech in the world couldn’t save Ronald Reagan’s face from looking like Michael Myers’ mask was left out in the sun for too long before being hastily dunked in a bucket of water and donned to be used to commit brutalist murders on unsuspecting American citizens. (And the rendering looks bad too).

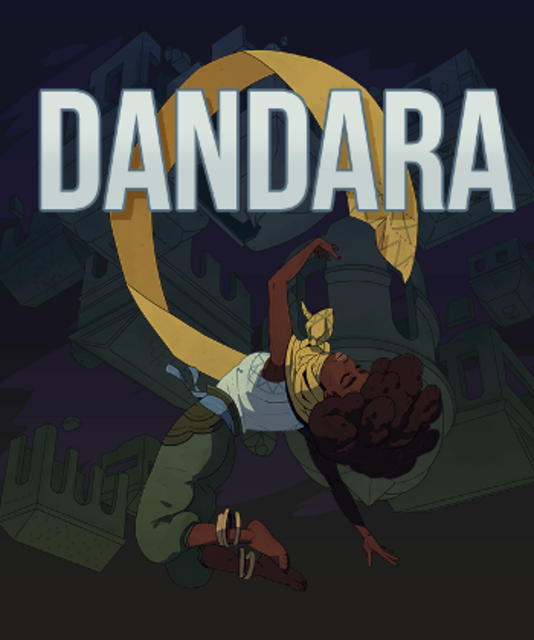

It’s with the idea of constraint that Dandara approaches its premise. And its premise sounds both so simple, and so complicated all at once: What if there were a Metroidvania-style game where the player couldn’t walk? What if there were a sprawling map to uncover, powerups and abilities to retrieve, bosses to fight and hazards to navigate, but nothing in the way of direct control? In a genre about player-driven exploration, removing the player’s ability to take full control of where they want to go seems counter to the very idea. The answer that Dandara provides is simple: instead of walking, the player jumps from surface to surface, only able to land on pre-defined points.

The ease with which this slides into place is shocking. Using the analog stick, the player can plot a course in a roughly-180 degree half-circle, and an icon will appear on any surface which can be leapt to. There’s a generous auto-aim on the reticle and a large icon that appears if Dandara is in range. If the icon says it is so, press the button and Dandara leaps through the air, and plants her feet assuredly once she’s reached her destination. Being restricted to having to leap away from Dandara’s current position, the world is then made to be ambiguously-oriented. Up is only up relative to you, and leaping from one foothold to another might cause the entire screen to flip or move to better allow a view of the action. It sounds confusing at first, but the confines of this design are so tight that creativity in the expression of the world can flourish.

The art design in Dandara is as beautiful and as vexing as the movement first presents itself to be. The opening area, a forest whose soil is beneath your feet and above your head and whose trees jut out in every direction, gives way to a village under siege by the army of Eldar. The telltale signs of a city are present, and the city is in distress: there are walkways and traffic signs bent and broken, doors which open to humble houses and residents who cower away from the ever-advancing regime on their doorstep. All of these parts are on walls and in the ceiling, beneath your feet and bending away at odd angles, existing in both the foreground and background. The floor is where Dandara’s feet are, and her feet change floors as fast as the player can flick the stick. As the game evolves, the environments become more exotic and generally less familiar as human architecture, but the initial impact of seeing a village exist at every angle never leaves.

At the end of the first area, the culmination of a tutorial, a massive head emerges from the shadows and tries to exterminate you. Here is where the movement and combat congeal to cement Dandara: Trials of Fear as a special beast in the genre. In the mold of Ridley in Super Metroid or Death in Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, the massive head of Augustus commands the real estate of the screen, filling it with projectiles, attempting to squash Dandara with his fists, and eventually fleeing into the blackness of oblivion while the player and Dandara give chase. Instead of fighting for opportunities to attack, the ability to plant on the walls means the player can dance literal circles around Augustus, chasing him through nothingness by bounding along walls, a tiny force of acrobatic vengeance who can’t- and won’t -be held down. I finished the sequence with my heart pounding, feeling every bit as masterful as I did exhilarated.

Unfortunately, the combat design doesn’t play to the strengths of the game design through to the end, unlike the fantastic art and world design. The extremely limited movement of Dandara means that combat is, by necessity, a slower and more measured affair than in many other action games. There is no frantically running back and forth across the screen to avoid projectiles, or inching towards or away enemies in a game of footsies and arena control. Like an anti-gravity Resident Evil 4, Dandara is rooted to the spot while aiming and firing her main attack, a very short-range energy blast, always either on the run or on the offensive. As such, the role of enemies for a large part of the game is simply to challenge your spatial awareness, either with their movement patterns or with projectiles that track Dandara in various ways. As the game enters its third act, the combat shifts gears into something that more closely resembles a bullet hell, filling the screen with enemies who fire multiple projectiles as well as move in erratic ways, blocking your potential escape vectors and flushing you out of your position. A particular enemy late-game acts as your counterpart, flipping from floor to ceiling when the player launches Dandara, as well as sending out a shockwave. While health is a non-issue that far into the game, I came out the other end of encounters with this flip-flopping enemy feeling as low as I did high when I shattered Augustus at the beginning of the game. Truth be told, I struggled through the final boss battle, despite being so tantalizingly close to the end. I even stepped away from the game for a week, sure that I wouldn’t finish it. As all the other bosses, it is a fantastic reveal, roaring into existence with an excellent soundtrack and imposing design, threatening to undo everything Dandara had worked for and egging me on to stop them from doing just that. It took the better part of a half dozen tries, and it was by no means flatly impossible, but because the design of the boss ran against the moments that I looked back on so fondly, it pushed me away. It was a boss fight of attrition, of enemies spawning in randomly and in great numbers, spewing projectiles from off-screen and blocking safe surfaces with their bodies. Much like Hollow Knight’s true ending, it wasn’t an insurmountable task, but it was one that seemed to abandon the greatest strengths of its design for sheer difficulty.

When the game is at its best, it is taking the well-worn tropes of the grandfathers of the genre and illustrating how much they can benefit from being flipped on their head. A particularly brave sequence sees Dandara in the game’s equivalent of the Mirror World from A Link to the Past, a twisted and corrupted flipside to the regular map. While at first intentionally isolating and borderline creepy, it gives way to what might have been civilization, at some point. And here you embark on a quest that brings you through facsimiles of Symphony of the Night-era Castlevania and classic 2D Metroid, self-contained puzzle boxes that adopt and subvert many of the level design tropes seen in those series. Of particular note is the castle section, a tightly-designed maze of (totally not-)Medusa Heads lilting through hallways and (totally not-)vampire men taunting you, to the point where I was expecting Dandara to be called a miserable pile of secrets. Thankfully, it avoids being cheeky and expresses a clever twist: what would Symphony of the Night be if up and down were relative? The audacity of Dandara to step so boldly into that territory and make it into one of the more engaging puzzles in the game speaks to the sure-footedness of the developers at Long Hat Studios.

On the whole, Dandara: Trials of Fear is an astonishing accomplishment in game design. It takes an abilities-driven exploration game and removes the simple ability to walk, but fills that void with movement that is more fun and more fluid than most of its peers. It answers a question that the game itself presupposed uninvited, and does it in a way that made me wonder why no one had been asking. The combat does overstay its welcome, becoming unbearably sloggish in the final moments of the game, but it never invalidates its own premise. If anything, I see an even greater game in the future, one that takes the lessons learned by the game’s bold expedition and applies them with a practiced hand. Dandara: Trials of Fear doesn’t always stick the landing, but watching it soar through the air is worth it.