A Thousand Roads: Modern Adventure Games

By Mento 6 Comments

I wasn't quite sure what to write about this week, since I was preparing my soul and sanity for another hectic E3 schedule - which, if you're not familiar with my foolish predilections, also involves a daily blogging series and many trailer reviews in addition to moderating the chat - when I realized that there was a certain throughline with some of my Indie Game of the Week articles whenever an Indie adventure game rolled around. Specifically, that the adventure game genre has broken out of the confines that once held it to a certain degree of formalism as more storytellers and visual artists took to our least gameplay-focused genre to see what they could conjure up.

Now, I've been a proponent of adventure games since my diaper years, madly mistyping commands for King Graham to shrug at before an ogre bashed his head in. The text adventure genre is even older, of course: the fact that King's Quest had images and an arrow key-directed control scheme made the game a brazen upstart as far as the old (or, I guess, older) guard were concerned. After that we entered the ICOM MacVentures and LucasFilm SCUMM era of graphic adventure games where the mouse had all but taken over for the keyboard, providing a wall of verbs across the bottom of the screen to invoke until they too were scaled down to a small number of contextual mouse clicks. That was shortly followed by the usually regrettable - but still formative - FMV period for adventure games, as serious (though it was usually "serious" with the quotes) filmmaker types tried their hand at an interactive Hollywood experience with real actors strutting their stuff in scratchy, tiny-windowed video files.

The adventure game took a little break after that, at least in turns of mainstream popularity, but it - like many antiquated genres - has since been resurrected into a new golden age of independently financed enterprises. The Indie market is so broad as to defy any kind of generalization, and that's as true for their approach to this renaissance of adventure gaming as it is to anything else: you're just as likely to see the release of a deliberately old-fashioned point-and-click adventure game as you are something bold and unrecognizable beyond the few traits that still technically signify it as belonging to the same broad genre. I want to go through a few of these variations for my own peace of mind after invoking a statement like "I appreciate that this game is going a whole new direction with adventure games" a dozen or so times while writing about Indies in the past, drawing from those I've played as part of my aforementioned IGotW feature and other blogs.

Text Adventure

We'll start with a few classic formats first. While the humble text adventure - one that is predominantly controlled through a text parser, and may or may not have a graphical user interface beyond text on a screen - isn't one that regularly makes the headlines whenever a new entry comes out, there's still a lot of support for it as a construct. It is, in essence, a place to start for literary types looking to pen a multi-branched narrative guided by a player's actions, at least until they have the means to produce games with more development layers to draw from (say, graphics or voiceover).

Rebranded as "interactive fiction" - which, like most genres, sounds very specific until you realize it applies to practically every video game besides the hyper-realistic - hundreds of IF creators have been using the open-source text adventure game engine Twine to pen their interactive exploits, taking advantage of the engine's relatively easy-to-use tools, either as a stepping stone to more ambitious projects or to cultivate a small following of fans who hang onto every paragraph of prose the author-developer can deliver.

- Recent Blog Examples: Nothing coming to mind - I type too much writing about games to want to do too much of it in the games themselves - but there was some on-site GOTY talk about a game called Arc Symphony a couple of years back which is based on an internet BBS for a fictional PS1 JRPG. Sounded intriguing, though I'm not sure where the story part comes in if there is one.

Graphic Adventures

As in, a point-and-click adventure game. A vaguely-defined evolution of the text adventure, that removed the text parser - though there was a time when games had both a graphical element and text, like early Sierra games - and replaced with verbs you could click on to manipulate a hotspot ("Pick Up," "Turn On," "Open," etc.). This was eventually reduced even further to simply "examine" and "interact". Movement was tied to the mouse as well, as players click the screen to create destinations for their protagonist avatar to move towards.

Graphic adventures - which, again, is a genre distinction that gets more redundant the further we age away from pure text adventures, sorta like "color television" - are the richest vein for nostalgic throwbacks from the Indie community. Throw a dart at the list of recent Indie adventure games - provided the site actually makes the correct distinction between "adventure" and something like Uncharted or The Legend of Zelda - and you're more likely than not to hit a deliberate throwback to the SCUMM adventure games of the '80s and '90s or their contemporaries. Not a bad thing, as combining the visual medium with a user-friendly interface that eliminates the ambiguity of text parsers provides the best marriage of storytelling and gameplay, or at least that was the case for the longest time.

- Recent Blog Examples: Thimbleweed Park, Chaos on Deponia, Subsurface Circular.

FMV Adventure

FMV, or Full Motion Video, was a technique to implement pre-recorded footage into an interactive format that first dawned in the laserdisc era and persisted with the optical media formats that followed. Initially these were gussied up QTE-fests like Dragon's Lair or Time Gal: the "interactive" part amounted to clicking the right buttons during the movie, or face being brought to an abrupt death screen before starting over at the last checkpoint. Adventure games adapted to FMV as a means to tell stories with real actors and not-so-real chroma keyed environments. To make the effect seamless between video cutscenes and gameplay, digitized sprites of the actors were used.

FMV games are generally criticized for letting the gameplay suffer in exchange for "realism" that, usually, was less successful than the FMV early adopters were hoping for. However, this did set some precedents that future Indie adventure games would pick up on: the first was the idea that you could effectively streamline the actual "game" parts to focus more on the narrative, reducing the number of inventory puzzles that would often be the meat and potatoes of the genre, and handing the keys to adventure game development to a wider audience of creative talents. Provided, of course, they were able to figure out how to make their stories work in an interactive format.

- Recent Blog Examples: Simulacra, Tesla Effect. (Honorable mention: Contradiction: Spot the Liar!)

Visual Novels / Sound Novels

Visual Novels (VNs) were popularized in Japan and inspired by Japan's early takes on western-style point-and-click adventure games like Yuji Horii's Portopia, which are far more "directed" by the game designer in how players will suddenly be forced into forward story progress by activating the right hotspots. To expand from that, Visual Novels are almost always entirely passive affairs where the player's input usually only boils down to occasional choices that can lead to branching narrative paths. VNs are marked by a considerable amount of dialogue, usually delivered as text with accompanying anime portraits of the talking characters.

As with text adventures, the relative simplicity in developing VNs has created a cottage industry of amateur enthusiast creators, most of whom rely on the freeware RenPy development toolset. Unlike modern text adventures, there are also still a considerable number of professional outfits creating games of this type, especially within the genre's native Japan. It's perhaps the adventure game subgenre least concerned with implementing interactivity - its close cousin the dating sim is the best bet for those in the market for something a little more mechanically involved - but has proven popular because of this more passive approach to storytelling.

(Sound Novels, incidentally, are text-heavy VNs that were more like radio plays in how they used sound foley and voice actors to deliver their narratives. Much rarer than they once were, sound novel pioneers Chunsoft occasionally release new ones like 428: Shibuya Scramble.)

- Recent Blog Examples: Fault Milestone One, Steins;Gate, VA-11 Hall-A: Cyberpunk Bartender Action.

Walking Simulators

I feel secure enough in using this name, since the "walking simulator" developers were quick to embrace it in their gregarious self-effacing humor. This is where we start to see Indie games start to explore modern alternatives to the classic models, creating detailed environments in first-person that players were free to turn upside down for as much incidental lore as they could want. I feel that this particular strain of adventure gaming started with RPGs like Deus Ex, Ultima Underworld, or System Shock: while these games had plenty of action and character progression, they were also known for their approach to environmental storytelling ("the art of placing skulls next to toilets," to quote Donut County's Ben Esposito) that led to some narrative mise en scène that thrived in an interactive landscape over which the player had an unparalleled degree of freedom to explore.

Since then, walking simulators have gone from strolling across inert settings taking in story details via a detached voice-over narration to highly detailed worlds filled with inconsequential bric-a-brac and notes that could weave their tales through more epistolary and subtext-heavy means. The only real connective tissue between them all is the first-person perspective: these notes and objects can only be carefully examined when held up to the player's face, after all.

Navigators

An expansion of the walking simulator, above, at least in terms of its embrace of epistolary storytelling. Navigators, or navigation fiction, are those games where the player is meant to explore a repository of data for the information they need to progress with the story. These games usually adopt a computer database interface, and can be combined with FMV (like Simulacra) or VNs (like Analogue: A Hate Story). You're looking through notes, diary entries, academic snippets, sometimes video or audio files, websites, computer code, or directly communicating with other NPCs to build a full picture of whatever mystery you're trying to solve.

It's a format that takes into account how people view the world in this day and age: through the filter of a tiny smartphone screen or computer monitor. While some have pointed statements to say about fake news on Facebook and other modern bugbears many simply choose to deliver their narratives through a medium we're all pretty familiar with; to enhance the verisimilitude of how we're consuming this information if nothing else. Games are also finding some pretty smart ways of subverting the familiarity of these devices, especially horror games with their unnerving glitch effects or sci-fi with their futuristic interpretations of information technology.

- Recent Blog Examples: Simulacra, Analogue: A Hate Story, Cibele.

Storiology Sims

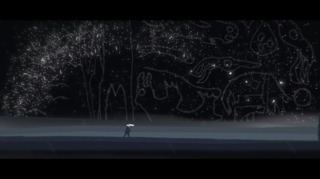

While I'm skeptical that storiology is an accepted term, this is a genre distinct not so much for its mechanics but by its intent. These are games where the goal is to shine a spotlight on the mythology of a group of people who lived at a particular time and place, and is built from what we know about their folklore and stories that have survived to the present day. In this respect, the game takes on a secondary role (some might say primary) of educating the player about these legends and the civilizations that told them. The games are usually designed to be as accessible to as wide an audience of would-be students as possible.

Most of the Storiology Sims I've played have been 2D side-scrolling games where the puzzles and action sequences are relatively simple and the game is focused more on delivering its content in a suitably atmospheric and thematically faithful way.

- Recent Blog Examples: The Mooseman, Year Walk.

HOPAs

Oh, these things. I went into a little bit of a HOPA fugue last year, playing multiple games of this oddly specific genre for the sake of my own edification if no-one else's. The HOPA - or Hidden Object Puzzle Adventure - takes the classic casual puzzle format of finding hidden objects in a scene (think Where's Waldo but with more junk) and couches it inside an otherwise standard first-person point-and-click framework which relies largely on inventory puzzles. These hidden object scenes are often accompanied by any number of other puzzle variations too, like sliding blocks, Simon Says, Pipe Dream, and really anything that has been the basis of a hacking mini-game at least once.

The reason I separate these from the adventure game herd is that they have a very specific, clear-cut blueprint adhered to by every HOPA developer I've ever encountered. If you're playing a HOPA you will realize it immediately just from the interface: seemingly borrowed from the old Legend Entertainment games, there's a first-person game window with a scrolling carousel of inventory items underneath and various important UI functions (the main menu, hints, collectible totals) in the bottom two corners. Though the interface might have any number of visual differences, and the themes and stories are relatively broad in their variety, they all more or less look and play the same.

- Recent Blog Examples: Abyss: The Wraiths of Eden, Enigmatis 2: Mists of Ravenwood, Grim Legends 3: The Dark City.

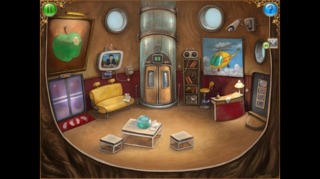

Exploration Clickers

I don't really know what else to call these, but this is the specific type of adventure game championed by Czech developers Amanita Design: they of Samorost, Machinarium, Botanicula, and (most recently) Chuchel. They're not the only ones making games of this type, where the player is encouraged to take in a large scene of moving parts and start clicking around to see what happens, but they've definitely become the face of this sort of child-friendly joy of discovery. Going further back, the Monty Python licensed games The Quest for the Holy Grail and Complete Waste of Time found plenty of opportunities for their trademark non-sequitur goofs with a similar format, where clicking on almost anything got you a silly visual gag or voiceover, if not usually much in the way of actual progress in the game.

I appreciate the earnest purity of these games, though that isn't to say they can't also have some tricky puzzles. The Samorost games in particular might depend on the player figuring out the right pattern of things to click to complete a puzzle, say by activating various stages of a Goldbergian device to get a key item from one point of the screen to where it can be collected by the franchise's nightcap-wearing protagonist.

- Recent Blog Examples: The Tiny Bang Story, Samorost 3, Botanicula.

Episodic Adventures

In many respects a standard adventure game narrative broken up into chapters that are released piecemeal, frequently months apart, there's something about how the episodic nature of these games and the method of their release influences certain mechanics and story beats that sets this particular variation apart. For instance, these games are far more likely to adopt some sort of "big decision" framework where the plot might veer in a completely different direction based on a single binary choice: Telltale's The Walking Dead, which often had you prioritizing the safety of one survivor and leaving the other to die, would end up creating many possible character ensemble variations by the end of its arc. Other developers have joined in on this idea since Telltale's rise with their zombie melodrama, the most successful of which is DONTNOD and their similarly melancholic Life is Strange magical realism anthology franchise.

Telltale's games prior to The Walking Dead were usually episodic too - I have a strong affinity for anything Homestar Runner related, and thought the Strong Bad game did right by the sharply silly wordplay and deeply referential sense of humor of creators the Chapman Brothers - but it was The Walking Dead that found a winning hook for a sales format built from financial necessity that happened to be prone to cliffhangers and stories that could be incrementally modified by the player's actions like a snowball gathering mass as it rolls downhill.

- Recent Blog Examples: Life is Strange: Before the Storm, Tales from the Borderlands, Dreamfall Chapters.

I've tried to select adventure game models that are not only distinguished by mechanical gameplay differences but also due to quirks derived by their development (episodic games) or their intent (educational storiology games), and yet I suspect I've only scratched the surface here. There's getting to be as many ways to tell stories as there are stories themselves, and the telling doesn't necessary have to adhere to some pre-conceived notion of how a video game narrative must be conveyed. Indeed, sometimes a fresh format like the deductive reasoning of Return of Obra Dinn also ends up being the best way to deliver its many chilling mysteries to the inquisitive player. I think as long as creative game directors continue to find new avenues to tell the stories they want to tell, and don't feel the need to stay fixed with standard formats like point-and-click or visual novels, this genre will continue to expand and draw in new fans.

Excepting the standard definitions of the established video game genres, which are themselves stuck in this nebulous and interchangeable quagmire, I could probably expand this list several times over by factoring in action-adventure games, or thematically unusual story devices like multiple narrator perspectives or time-travel which tend to inspire divergent player interfaces in addition, such as the exploitable "NPCs on a schedule" logbook system found in time-loop games like Majora's Mask and Gregory Horror Show (and, I've heard, this month's Outer Wilds). Or the recently released Heaven's Vault where the story and the player's understanding of same depend so heavily on the player's perspicacity when it comes to deciphering the game's ancient language. I love how versatile video games are proving to be in telling extraordinary stories and finding ways to expand or uniquely factor in the player's role in same, and I hope this trend continues for many more years to come.