That Wasteland Feeling

By ahoodedfigure 18 Comments

The wasteland and me go way back.

When I was young, before I was even in school, the scare tactics began. I remember seeing a graphic in a newspaper showing Russian nuclear stockpiles, with the missiles looking huge on the graph compared to the tiny American ones. Orson Welles, a man I trusted because he did advertisements for my favorite board game of the time, Dark Tower, starred in an exploitation documentary talking about the end of the world, showing missiles launching from secret bases to destroy us. Public Television tried to help kids by having a special, "What do Kids Think of the Bomb," but I couldn't get past the opening titles with their droning, horrifying monotone voices. Seeing I was distressed, I was told by one of my parents that a nuclear bomb would wipe us out before we even had a chance to suffer through the aftermath, but such fatalism was (and is) no comfort to me.

Missile Command

The prospect of nuclear war was my first real fear, and Missile Command was probably my first way of combating that fear. You were doomed to die in that game; the waves just got more intense until you were wiped out, but at the very least you could take direct action in fighting back. It was probably the start of my cold-war obsession with fighting the evil reds, and it would take many, many years for me to realize that little kids in Russia were being exploited just as much as I was.If you're not familiar with Missile Command: you have a set number of cities you have to protect with anti-ballistic missile silos. Waves of missiles rain down as straight lines above them, and both the cities and the silos are vulnerable to attack. The easier missiles just emerge from the top of the screen, but these missiles could split into several warheads; these MIRVs would help fulfill the missile quota for a given round even if it looked like you might wipe out all the missiles early. Killer satellites and bombers would start at about half-way up the screen delivering warheads, which decreased your reaction time if you couldn't wipe them out before they could fire, and in advanced stages smart bombs would actively dodge your anti-ballistic missiles, making them much harder to take out. When silos were lost, you lost some of your anti-ballistic missile stores, and if all your cities were gone at the final tally, assuming no bonus cities were awarded for your current score, the game was over.

I was taught that was pretty much the end if that was to happen to us. Once civilization was destroyed, the nuclear fallout would get rid of us in ways I couldn't understand, a plague with no survivors.

The games I played then, on video game consoles and on the playground, were all about stopping the forces of destruction and avoiding this fate at all costs. It wasn't until later that I realized there may be some sort of life after the death of the world, at least in the realm of fantasy.

Road Blasters

It wasn't until after films like The Road Warrior, The Terminator, and A Boy and His Dog that you started to see more POST-apocalyptic games. I think it was in part because the idea of annihilation seemed a bit less emergent than it used to, or that our imaginations weren't so advanced that once we started to ask what comes after, all we could think to do was make everything else go away or become mangled beyond all recognition, but let ourselves somehow remain unchanged.One of the major components of this wave of post-apocalyptic entertainment was a return to savagery. It's never really left, in part because we wouldn't have as much fun if everyone just tried to rebuild. Star Trek, believe it or not, is based on a post-apocalyptic setting, as was the Buck Rogers reboot, but the rebuilding part is skipped, even though there's struggle there, because everyone needed to work together in order to find some semblance of order. Going for the cheaper, more obvious conflicts later was an easy decision to make.

Games started to capitalize on our instinct to survive, and many took a lot of lessons from old Mad Max. Road Blasters was one of my favorites: a racer/shooter where you drive on tracks, gaining fuel by running over globes, trying to blow up or avoid everything in your path to reach the next checkpoint. No more civility like in Pole Position; this was more Spy Hunter without worrying about innocents, or the relatively non-lethal, genteel attitude of later games like Road Rash. If you were on the road, you were fair game. It even had nuclear weapons, if you doubted its suggestions of the post-apocalyptic.

But here, still, there was a structure of a sort: you were still expected to race. For games to truly capture a bit of the anarchy of the post-apocalypse, a bit more depth was called for.

Wasteland

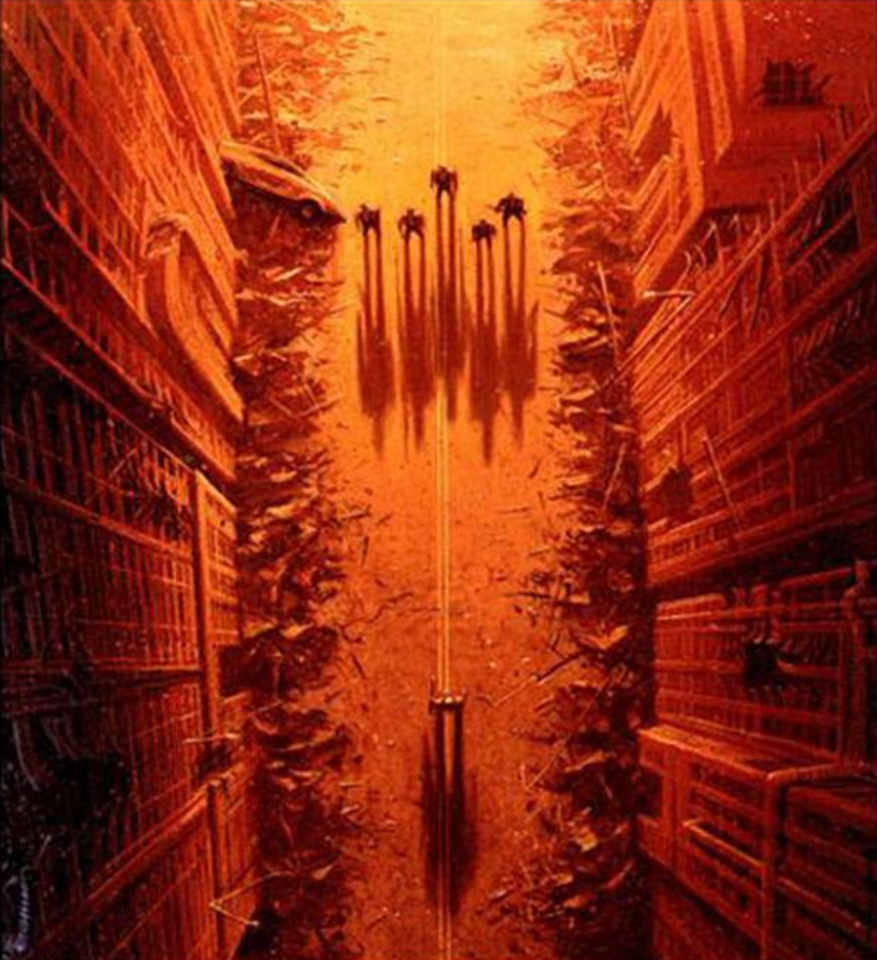

In my friend's basement was a Tandy with monochrome monitor and PC Speaker sound. Through that machine I got to see Starflight for the first time, staying up late in that dark room trying to figure out how to appease these mysterious ships that kept attacking us. Another game that left a strong impression on me though, was the now famous Wasteland. The cover art pretty much told you everything you needed to know: the world was ruined, humanity has fragmented, and nothing was certain, so watch your back.From what little I saw of the game, the humor wasn't lost on me: one of the first enemies I saw were the nuns-with-guns. But it was the realistic weapon names that stuck with me. This wasn't some abstracted fantasy version of the future; there were leftover bits of the old world there, and players were expected to wallow in it.

It would be a long time before I ever actually got to play it, since the guy that loaned it to my friend demanded it back before too long. It stuck with me, though, and when I finally played the thing I was amazed at how different the game was from my expectations. Going from monochrome to color isn't always a good thing depending on the color palette (not palate, not pallet) you have available-- at least in black and white you can imagine what the colors look like, and actually getting into these old time RPGs I was sort of surprised how breezy the games often were with their satire, which ruined the tone a bit for me.

Tone is something very hard to get right in these sorts of games, I think, because if you brood too much you risk having the fight for survival feel a bit meaningless or overbearing, and if you pile on a bit too much comedy you distance yourself from the pretty horrible prospect of humanity crushing itself. The tone I wanted, at least, was more illusive than a dude with robot eyes smoking cigarettes.

At least until Fallout came along.

Fallout, and the Theme as a Whole

A lot's been said about this game and its sequels, but for me what stood out was its tone. A big part of that was captured in Mark Morgan's score, which undercut what could have been a pretty silly satire on 1950's optimism's glaring nuclear omissions, giving the funny stuff an eerie, haunted counterpoint that fit perfectly. Balancing that tone is always difficult, and at times Fallout's tone moved too far in one direction for me, but it was the first post-apocalyptic game that really lived for me. It even had some rather ugly moral issues, and nothing was as straightforward as it would have been in a less complicated RPG. Life was brutal, death could be pretty messy, and there was just enough of a connection to a recognizable past that even the alternate history felt authentic, if at times distracting.

By the time I played Fallout I still liked post-apocalyptic settings, but my need for them had waned a bit. I was no longer as terrorized by the possibilities of nuclear war as I was as a little kid-- it probably caught me at my most politically optimistic period in my life and so it didn't have quite the impact it might have had.

Most of the post-apocalyptic games and settings I've experienced tend to emphasize that the old rules don't apply anymore, that taboos will be broken, that the obstacles that now stand in the way of both simple kindnesses and mindless savagery make life a bit false, and If civilization gets stripped away, you'd know who your friends and enemies really were. Zombie settings definitely cash in on this, so in many ways they're just another way to get rid of society and start over.

Maybe that's why these settings continue to appeal to many of us. We got past the horror of actual annihilation and started fantasizing about what it would be like if the annihilation was selective, if it didn't get rid of everything, if it didn't get rid of us. Sure, it would be ugly, but being an adult now, with a long list of mistakes and plenty of potential to make more, burning that list doesn't sound so bad.

So while it seems the little kid in me is being betrayed by these fantasies of destruction, they really seem to be two separate entities, one that fears death, and one that fears stagnation. Yet both seem to have an idealistic core: whether we prevent our annihilation through a change in behavior, or we adjust to the consequences of that behavior after our fall, both paths seem to have just enough faith in our ability to rebuild the world on more solid foundations.

Epilogue

What inspired this post was this relatively well-done fan film called Fallout: Nuka Break. It's sixteen-and-a-half minutes long, and pretty decent. (via RPS)I'm continually surprised by the post-apoc stuff I stumble upon, long after my mania for the genre's died down. I'd never heard of Radioactive Dreams until doing research for this article.