Trading survivalist brains for gun-toting braun: A Fallout 4 critique

By BizarroZoraK 4 Comments

Note: I spent months working on this review to brush up on my writing abilities, and it turned out to be a long, disjointed mess. It's so bad that I don't even want to post it as a user review on the Fallout 4 page. I decided to post it here on my personal blog anyway to serve as an example of how not to write a review.

Huh. The Wasteland sure is brighter and more saturated than I expected.

I like it, though, at least on the surface. Sure, the gritty, irradiated green tint of Fallout 3’s Capitol Wasteland made more sense for a post-apocalyptic milieu, but the colorful Commonwealth is more inviting and pleasant to look at. On the other hand, if you really want to read deeply into this palette choice, you could interpret it as one of several examples in which Fallout 4 acquiesces to more mainstream and accessible game design trends, and this extends beyond the visuals and into the gameplay. Where previous iterations of Fallout conveyed a dangerous, deadly setting in which wit and deep strategy were required for survival, the streamlined combat and simplified role-playing systems of Fallout 4 communicate a message more along the lines of “Hey, welcome to this fun, colorful shooting gallery!”

Does this make Fallout 4 a wholly bad game? I don’t think so, but I do think it has some glaring flaws that hold it far back from perfection.

Simply put, Fallout 4 is an action first-person shooter with some RPG elements. If you're willing to accept that, you’ll find that Bethesda has crafted an incredibly detailed open world experience with tons of locations and stories to discover. But I’m a little biased. I had already accepted Fallout 4’s fate as an action game long before buying it on a Steam sale for $30. If I had purchased it at full price expecting a deep, complex RPG in the spirit of previous Fallout games, I might be a little more disappointed.

In its pursuit for something more accessible and mainstream, Bethesda is quick to (attempt to) shed its previously clunky presentation and gameplay within the first couple hours of Fallout 4, and it’s at least initially successful. That fancy pre-war intro sequence shows off some nice graphical and presentational advancements, especially in terms of environmental detail and facial expressions. And hey, your character has a voice! Granted, this concept stops being novel shortly after this intro sequence (more on that later), but I appreciate that Bethesda ditched their silent protagonist schtick to try something new. It’s obviously a very short and controlled portion of the game, but it makes a decent first impression by showing that Bethesda is capable of working through their historically janky, robotic animations to produce a good-looking cinematic setpiece.

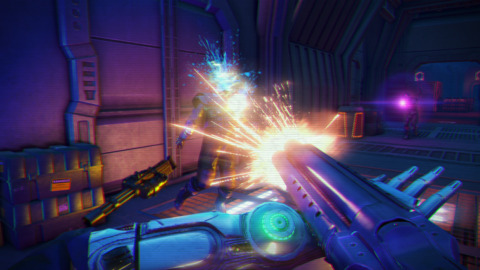

Then once you’ve gone through the series-signature vault escape and begun your family redemption story, the first couple things you encounter on the surface are a 10mm pistol and a molotov cocktail. After the first couple fights with these weapons, it becomes plainly clear that combat has become a focal point of Fallout 4’s design, and it’s the part of the game that I engaged with the most. Having a dedicated grenade/melee button and precise ironsights aiming is a much bigger deal than it sounds. These control and mechanical refinements finally put Fallout on par with other shooters on the market, and while these changes have probably come several years too late, they’re still very much welcome. If you’re good at aiming, these refinements almost completely invalidate the VATS system. You can still use VATS if you like, but its slow-motion function feels out of place with combat mechanics that are supposed to be fast and frantic.While this may be a natural progression considering the series’ lineage, the move from slow, methodical, menu-heavy gameplay to a more modernized twitch-shooter experience feels like quite a departure.

This increased emphasis on combat brings a decent variety to the setup and scale of enemy encounters. At the smallest you could be fighting one-on-one with a raider in tight corridors, and at the largest you could be defending a whole colonial fort with 30 or 40 active combatants. Likewise, the environments in which combat takes place are pretty diverse. Whether it be small interiors or large outdoor locales, the battlefields are well designed with plenty of verticality and flanking opportunities in mind. The game also allows for different approaches to combat scenarios, as stealth and long range sniping work just as well as ever if you don’t want to barge in guns blazing. There’s clearly an effort to make every moment of the gunplay feel different, and that effort is usually successful.

Sadly, a lot of that effort is also ruined due to the game’s lack of variety in difficulty. This is where Fallout 4’s uniquely inviting nature becomes a problem, as the game is generally too easy. Even on Hard (the 4th of 6 difficulty levels) I almost always had plenty of ammunition and stimpaks to survive through thick and thin. The rare times when the game does spike up in difficulty tend to be jarring and frustrating experiences: on numerous occasions, I was immediately killed by a deathclaw or a missile launcher-wielding raider that came out of nowhere, only to realize I hadn’t saved recently, meaning I just lost at least 10-20 minutes of progress. With all that in mind, I would suggest setting the difficulty as high as you can handle, but be prepared for a few random deaths and save often.

Given Fallout 4’s inviting and welcoming nature, however, it’s probably not supposed to be a consistently hard game anyway. Fallout 4 doesn’t just want you to find satisfaction in surviving a grueling battle. It wants you to find satisfaction in the simple RPG pleasure of making numbers and progress bars go up. Indeed, Fallout 4 doesn’t have a level cap, so if you’re patient enough, you can keep killing things and completing side quests to fill that level bar over and over again. This also means you can level up every SPECIAL attribute to 10 and unlock every perk in a single playthrough, which is kinda cool in theory, but it also means that you aren’t creating a character with your own unique specialties as much as you are creating a jack of all trades. It seems like it would make subsequent playthroughs feel less unique.

Furthermore, Fallout 4 ditches the stressful equipment maintenance and most of the survival-oriented parts of the combat in favor of a more loot-driven system that reminds me a lot of Diablo and Borderlands. Each type of enemy has their own variety of leveled ranks, and they all drop seemingly infinite permutations of modified weapons and armor. For example, instead of just finding a regular 10mm pistol, you might find a “Muzzled Advanced 10mm Pistol” with a green dot sight, or a “Suppressed Hardened 10mm Auto Pistol” with silent, rapid-fire capabilities. You can also obtain these modifications through a surprisingly in-depth crafting system that utilizes all the random junk in the wasteland to make each piece of gear feel fairly unique. Better yet, crafting is more fun than maintaining and repairing equipment. In my experience, however, finding enough resources to craft meaningful mods was usually a chore, and the game seems to encourage killing and looting enemies to get the best equipment anyway. Higher-level baddies will drop better, harder-to-obtain loot, and you can even find “legendary” enemies who possess gear with unique effects that you can’t get anywhere else, like incendiary shots and the ability to deal more damage when you’re health is low.

Fallout 4 focuses heavily on combat, but sometimes you’ll want to take a break from your murderous rampage through post-apocalyptic Boston to engage with the game’s other features. Indeed, the game is a multifaceted beast, but if you’ve read any other discourse on this game, you’ll know that its other facets, especially its overall narrative, have been fairly contentious. Fallout 4’s world and some of it's storytelling carries that cinematic, imaginative ethos from the aforementioned intro sequence, which is successful at some points and borderline disastrous at others.

Not surprisingly, Fallout 4 is resoundingly successful at offering a large, detailed, storied landmass that players can sink their teeth into for hours. The Commonwealth is certainly a well-realized world; Old radio signals and terminal entries tell an eerily vivid tale of what Boston was then, and all the settlements, shops, and cities across the wastes paint a dreary, humorous, and sometimes uplifting picture of what Boston is now. It feels much more densely packed with points of interest than, say, Skyrim or the Capitol Wasteland, and it’s very well suited to aimlessly wandering around and discovering little stories and sights. During my own travels, I found a horse race track with appropriately named robots perpetually running around the track, a locked-away protectron whose sole purpose is to serve beer and tell dumb jokes, and a quarry on the site of an ancient temple in which workers performed human sacrifices. Finding random, funny stuff like this is my favorite thing to do in any Bethesda RPG, and Fallout 4 is no different.

“Dungeon diving,” so to speak, is also better this time around because all the locations and interiors don’t feel quite as copy-and-paste as they did in Fallout 3. You may encounter some repeated assets here and there, but all the buildings and the puzzles, stories, and combat scenarios within feel much more uniquely hand crafted. The abandoned vaults scattered around the Commonwealth a particularly good example of this, hiding plenty of little side quests based on stories of corrupt overseers and nefarious research.

My favorite part of the dungeon diving is reading pre-war terminal entries and finding the post-war remains of the stories they tell. Here’s a simple, not-so-spoilery example: Within the offices of Shaw High School you can find the terminal of a disgruntled principal who has been tasked with raising his student’s standardized test scores. To accomplish this, he distributed a bunch of Mentats among the kids, then used the increased school funds from the improved test scores for his own frivolous means. Using a nearby key, you can then open the Principal’s office and find stacks of Mentats for your own use. You can also find one of the student’s personal terminals and see his writing skills in his logs improve as he starts taking the Mentats.

The random, organic events that can occur in your travels are also pretty entertaining. You could be strolling along the Cambridge area, and suddenly you’ll see a flurry of lasers flying by between a group of Super Mutants and a fleet of Brotherhood soldiers, and then a Vertibird will come crashing down in a fiery explosion… Okay, so they use the exploding Vertibird trick a little too often, but it’s still a cool organic setpiece moment. In less dangerous parts of the Commonwealth you might find a couple NPCs sharing words about recent events or gossiping about local rumors, which can lead to information on the greater narrative or just minor side quests. Whether it be peaceful conversations or violent combat, the ways in which the people and creatures in this world interact with each other make this otherwise barren wasteland feel surprisingly lively.

This liveliness shows that there’s a real effort among the inhabitants of the Commonwealth to rebuild Boston and restore the peace and prosperity they once had. The game lets you play a part in this rebuilding effort by letting you use the various junk you find in your travels to build your own settlements. The settlement building mechanics work similarly to the weapon and armor crafting, but obviously on a larger scale. Once you’ve established a settlement and a few residents, you can build a wide assortment of housing, furniture, bedding, stores, and food and water sources in an effort to keep your settlers happy and resource production high. Sadly, the few items you get from settlers aren’t any better than the stuff you would find out in the wasteland by yourself, which makes settlement building seem inconsequential, but it is still fun to toy around with the assets that the game gives you and test your architectural design abilities.

You’ll also have to build defenses and turrets to protect your settlements from incoming enemies, and this is where settlement building becomes much less appealing, especially because the game encourages you to maintain dozens of small settlements all across the Commonwealth. These random settlement attacks happen very rarely, so it’s not too annoying, but the game doesn’t give me much of a reason to go through the trouble of building up multiple settlements, which makes the whole thing seem even more pointless. I would much rather just focus my work on one big settlement, and thankfully, I was still able to do that. I claimed the first Sanctuary settlement as my main base of operations and put most of my building effort into that area.

It feels weird to spend so many words discussing all this largely superfluous side content before even touching on the main quest. That’s probably because the main path the game tries to lead you on happens to be the most underwhelming and disappointing path. Admittedly, the initial promise of the main storyline had me excited, with sentient androids (or “synths,” as they’re referred to in the Commonwealth) serving as a central part of the narrative. Bethesda explores some compelling themes with android rights and the idea of putting a human consciousness into a robotic body and vice versa, but that’s obviously not treading any new ground in the sci-fi genre.

The overarching faction interplay that makes up the main questline was also initially exciting. The Brotherhood of Steel, a jingoistic military order that seeks to regulate technology in the wasteland; the Minutemen, a grassroots organization dedicated to protecting the commonwealth; the Institute, a technologically advanced group of underground scientists that manufacture synths; and the Railroad, android sympathizers who work to save synths from the institute: They all have their conflicting pros and cons, their own motivations for protecting or rebuilding the wasteland. The ways you choose to fit into their interactions almost evokes the faction system of New Vegas, sometimes leading to tough decision-making and actual roleplaying. Completing a major quest for one faction can force you to fail a different quest and potentially affect relationships with companions.

Unfortunately, these gameplay implications aren’t really as impactful as they should be. Without spoiling too much, the story eventually devolves into a binary pro-Institute or anti-Institute pursuit, with some minor ending quests to resolve conflicts between the remaining factions. Aside from this, the aforementioned quest changes and maybe some new ambient dialogue, the Commonwealth never feels very different from the result of your actions. It’s concerning that this narrative falls so flat because it suffers from some of the same problems that Skyrim had. It’s plagued by shallow writing, limited player input, and a general lack of urgency. Fallout 4’s attempts at cinematic visuals and thematic exploration can’t save it from these problems.

The dialogue system is also a huge letdown, and this is where having a voiced protagonist becomes more a curse than a blessing. Perhaps as a measure to minimize work for the voice actors, your dialog choices are limited to four lines that can be boiled down to “positive,” “negative,” “neutral,” or “sarcastic,” whatever that means. That’s the problem: you don’t entirely know what you’re going to say until your character blurts it out (this can partially be fixed with a mod), and too often this can lead to inciting the wrong reaction from the person you’re talking to. The larger issue with the dialogue is that it’s so frustratingly prone to immersion-breaking quirks and bugs. Too often I’ve had random passersby push me off camera during conversations, multiple people talking over each other trying to give me different quests, and interactions ending in a solid 10 seconds of silence. Say what you will about the corny voice acting and stilted animations of previous Bethesda titles, but at least this weird stuff rarely, if ever, happened.

The rote quest design doesn’t help matters. While there are a few standout missions in the main story, the large majority of the quests, especially the radiant side quests, usually involve going to a specific location, clearing out all the enemies within, and maybe retrieving a specific item. Aligning with one of the factions will really start to pile on these side quests ad infinitum. And it’s not just the Minutemen and their infamous settlements that need help. Both the Railroad and Brotherhood of Steel frequently sent me to go help this researcher or go clear out that building. A lot of these radiant quests seem to be designed to make the player discover new locations on the map, which seems weird because I would gladly explore the map on my own. Variance in quest design is almost nonexistent here, which really drives home the “less RPG, more FPS” point that has garnered this game such a contentious reputation.

All of these problems are exacerbated by the long-form nature of Fallout 4. Bethesda obviously wants you to spend hundreds of hours in this game, but beyond the combat and some of the random map exploration, there doesn’t seem to be enough interesting stuff here to keep most players engaged for that long. It’s really unfortunate that so much of the experience feels padded out with tedious quest design. According to Steam, I’ve logged a little over 80 hours in Fallout 4, but it feels like so much less than that because the gameplay loop I’ve fallen into often feels too routine and repetitive to be memorable.

And yet I still keep coming back to it. It tickles the parts of my brain that are so easily satisfied by finding new loot and watching my level bar go up. I was constantly rewarded with better stats, more power, more currency, larger numbers. Much of this gameplay loop is a continuation of Fallout 3 and Skyrim, but Fallout 4’s emphasis on action more so evokes a comparison to Diablo and Borderlands. It’s a simple, yet very effective, satisfaction. All of those other immersive systems, like the stealth, the computer hacking, the settlement crafting, the faction and companion interactions, it's all a nice layer of icing on this big, dumb cake.

Of course, those systems should be so much more than icing. They should be the core of the cake. They should actually be immersive. Bethesda should have leaned into those role-playing elements that make Fallout special, but in Fallout 4 those elements often feel like decoration to make the game seem deeper and more nuanced than it really is. But like I said, I knew I wasn’t going to get a deep RPG before I played it, so the little bit of nuance that was there was a pleasant surprise. The simple mechanics and reward loop of Fallout 4 make it an experience that I can easily come back to every few weeks or months to knock out a couple quests or check a few new locations off the map.

I feel like I’m in the minority when I say that Fallout 4 is still a pretty good game, but I do believe that Bethesda can’t get away with using this formula again, and they certainly can’t get away with dumbing it down any further. If they intend to make more first person RPGs, they need to shake things up and return to some of the elements that made games like Daggerfall and Morrowind so special.

Log in to comment