Zelda's Missing Link

By Daneian 11 Comments

Early on in A Link Between Worlds, the travelling merchant Ravio takes up shop in your house, lines it with the franchises complement of items and offers to rent Link each and every one. This event single-handedly eradicates the suffocatingly linear item-based progression that had reached its logical conclusion even before Twilight Princess put its staggering deficiencies on display. A Link Between Worlds is in many ways an alternate take on an old story, one that reveals its true ambitions at the beginning of the second act as Link squeezes through a tear in the fabric of Hyrule and discovers that every inch of the world and its seven palaces are accessible with the right tool in hand.

The series changed dramatically with A Link to the Past. What originated as a tough, tightly-paced open-world quest in a mysterious land where you could enter the eighth dungeon before you found the first evolved into a narratively-driven hike along a narrow trail that offered regular rest stops but few forks. Then the series transitioned to 3D and extrapolated those concepts out onto increasingly larger scales, maintaining the limited structure while increasing the world’s geography. Nintendo tried to recapture LttP's magic by recasting the same spells. Zelda became an adventure at odds with itself and desperately in need of rethinking. It’s inspired then that A Link Between Worlds chose that divergence as the point to draft ideas that remain fresh despite their age onto a fully explored landscape. It brings Zelda back to the Hero’s journey it once was.

And by placing him in LttP's familiar territory, Link’s kick into action is really a soft pat on the fanny. LBW’s got the fireball spewing Death Mountain, the sleepy Kakariko Village and the hydrated Lake Hylia. It’s got the item-based dungeons. It’s got the three act structure. It’s got the duality of universe. But rather than revisiting Hyrule’s corrupted Sacred Realm, the punticularly-named Lorule is the twisted reflection of the great kingdom right down to its dark haired Princess Hilda. This time, the powerful Yuga is the force seeking to resurrect Ganon once again and steal the Triforce. You know what comes next, seven sages and all that jazz.

You’ve seen villains like Yuga before, the snobbish, almost aristocratic type so obsessed with perfection that he captures beauty and seals it away behind glass and inside frame. The archetype is functional here, helping LBW’s new gameplay mechanic integrate into the fabric of the narrative. By flattening himself against sheer surfaces, Link has new ways of moving across known geometry. Essentially defined as on-rails sequences, the paint mechanic provides a new perspective on the series brand of traversal, one that prioritizes spatial puzzles over manual dexterity. As interesting as the painting concept is, for how well it’s applied, for how it mixes up the flow, it never quite coheres with the foundational gameplay. The two textures in the same bite just feel a little off.

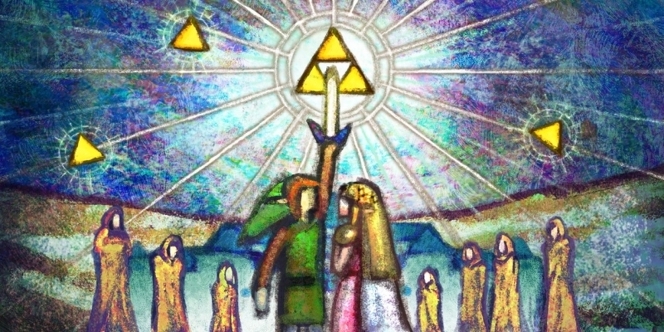

But that’s not the case for the art design. The stained glass motif has been used elsewhere in the series, first appearing as the aesthetic treatment for the Hero of Time prologue in Wind Waker. As there, it has a cathedral tone that contrasts the straight forward style of the game world and is appropriate for the aura of Divinity that the series has adopted over its run. Considering how much love music gets from Zelda, it’s nice to see some of the other Arts shown reverence.

The mechanic is exaggerated by the modulating sound design, causing the music to distort and recede, making the great, complex compositions become as one-dimensional as the visuals. It’s cool. So too is how the paint mechanic is introduced, given to you after beating the game’s first dungeon and its use subtly explained as you make your escape.

That moment you see those seven ‘x’ marks penciled to the map on your 3DS touch screen and realize you’re responsible for cutting your own path is impressively profound. Even if you hadn’t played A Link to the Past, you had come to know the sunlit Hyrule pretty well by the time you slipped through the panes of reality. Now you’re in this destroyed mess armed with a few weapons and a lot of options. It’s strangely beautiful and unnerving.

Between Worlds may feature the typical set of dungeons, but all nine are compact enough to complete in a snap but complex enough to explore a full concept. Though few of the items are unique to this game and only one has a limited use, the complete set is more versatile than has been the case in some of the past Zelda’s and can cater to your preferred play style whether that’s melee or ranged attacks or enemy management. Since every item eats a chunk of the shared stamina pool, combat is about precision of action rather than freneticism. That sand battle is pretty nifty.

Though you can eventually just buy everything, renting imbues the gameplay with a great sense of risk up front. Get knocked out, and Ravio’s little blue-feathered thug will swoop down and swipe the goods from your unconscious heap of green elf boy. That’s a great idea, an almost Dark Soulsian design philosophy applied to a staid Zelda system. It turns the death counter into a practical gameplay mechanic where it had only been a badge of shame and finally gives you something to blow all those stacks of rupees on. Praise Nayru.

The unfortunate irony is that for all the advantages to the elegantly simple open world design, the times when it doesn’t offer direction blatantly stand out. Whether it’s missing an item or the game’s main side quest, it can be supremely frustrating to miss that one villager you needed to talk to or that one cave you needed to enter and not realize it until the end of the game. Trust me. Yet here’s a secret: neither of those cases matters in the long run. This is easily the breeziest entry in the franchise.

Zelda has always been at its best when it’s simple and quick. Though 2D visuals are hardly novel for the series, Between Worlds benefits from its use, the most obvious of which is that it keeps the world tight and concise. The economy of space means that you’re never more than 15 seconds from something interesting. Unlike the larger 3D titles, world traversal is rarely tedious. To make it faster, not only is there the robust fast travel system a button away but there are dozens of tears spread out so Link can easily slip through the cracks. The game gets you moving and never brakes until you find yourself at the final boss. It’s magical.

A Link Between Worlds gives us a peek at a parallel universe version of one of videogames most important series. It’s intriguing to ask what great adventures Link could have embarked on if The Legend of Zelda had made a different choice in it’s Past. Perhaps that’s a question not worth answering, but maybe this one is: what does Link do with all those items after he’s saved Hyrule? He probably sells them.