A Better Difficulty III: Hitman

By gamer_152 5 Comments

Note: The following article describes some mission details from Hitman (2016) and Hitman 2. I've tried to limit the spoilers to the early levels of each game, but if you want to solve all these missions for yourself, you may want to play up to Club 27 in Hitman (2016) and Another Life in Hitman 2.

Last time on whatever this is, we looked at Forza Motorsport 6. We analysed it as a game that goes beyond tightening or loosening a few aspects of its challenges and leaving the player to figure out how to perform. We said that it instead allows the audience to construct a game that suits their abilities and desire for challenge. We observed that that game achieves its goal of honing player skills by taking the following steps:

- Accounting for the player having different skill levels at different activities.

- Incentivising them to take on more demanding tasks.

- Giving them a safe space in which to experiment with the mechanics and interface.

- Allowing them to practice the same tasks repeatedly.

- Letting them adjust the difficulty of the game on the fly as they acclimate to the challenges.

- Lending them a clear idea of the actions they need to take to succeed.

- Giving them clear, immediate feedback about the quality of their performance.

- Giving them a clear idea of alternatives to their current approach, especially when failing.

Forza Motorsport met these requirements through mechanics like modular difficulty menus, the Driving Line, and the Rewind. However, in that article, I also mentioned that if you're trying to nurture the player's abilities in a non-racing game, you can't just transpose the mechanics from Forza onto it. There's no "traction" in Mr. Do!, so we could not map Forza's Traction Control onto its movement. Bust-A-Move does not involve piloting an avatar through 3D space, so there's no way to port Forza's Driving Line into. Any one method for helping the audience master play must be designed for the relevant play format. Work with a different type of game, and you will need different mechanics. But even understanding that, it can be challenging to see how implementing our bullet point goals would work outside of driving titles.

Another concept we must understand: the player and designer's tight control over the difficulty in Forza is a product of the game's relatively limited possibility space. In Forza's races, players continuously move forward around an explicitly outlined loop, with their only choices at any one time being to accelerate, brake, turn, and change gear. This does not mean that the game is shallow or necessarily easy, as judging exactly when to make each choice is a subtle art and executing each manoeuvre requires precise inputs and an intuition for physics. However, we should consider that plenty of games that aren't Forza have more tools, goals, areas, and general gameplay elements bumping around in them. When we do that, creating a comparable environment for skill improvement in other games suddenly seems painfully complicated.

Yet, as the rebooted Hitman proves, it's not impossible to account for that complexity. Playing this series does not, for a second, feel like playing Forza, and yet we can see the same underlying concepts that drive Forza's design, underpinning Hitman's. It might sound unlikely that a stealth action game has an equivalent of the Driving Line or the Rewind, but they're in there if you know where to look. Single-player games generally put us through a period of onboarding. We need to feel them out, internalise the purpose of all the tools they give us, watch for patterns in the game state, and sometimes acclimate to new mechanics. All that is true of learning to play Hitman, but adapting to Hitman's challenges means much more than getting cosy with the basics and grasping a few level-specific concepts.

The objective in each of its missions is to kill all our assigned targets. Every one of its maps has unique costumes that get us access to areas closer to our targets, unique methods with which to kill these antagonists, and unique escapes for after we've dispatched our victims. Levels also contain "Challenges", which reward us XP and sometimes unlocks for exploring, roleplaying, or assassinating in a prescripted way. For example, slapping someone into the ocean with a fish or delivering flowers to a grave. In some cases, the processes to obtain costumes can also be specific to the stage. IO Interactive, the developer, designs missions not for us to beat once and then discard. They make them for us to play repeatedly, exploring different routes and strategies each time.

In most single-player games, the player must execute on a pre-built solution to their current predicament or pick one from a metaphorical menu. They may encounter a puzzle where the designer dictates the order in which certain weights should be put on specific pressure plates. Or perhaps the developer has laid a corridor of monsters out in front of the player, and the player must decide what combination of firepower and psychic abilities they use to blast through it. In Hitman, the sheer volume of options available at any one moment makes participation less a case of picking a solution and more a matter of inventing one, a bit like in a grand strategy game or one of Zachtronics' creations.

Of course, to make informed decisions in how they construct an approach to a mission, players must develop an intimate understanding of the features of the map they're playing on. In Hitman, your level of applicable knowledge drops whenever you begin a new mission. There's a convincing argument that the most intimidating part of a Hitman stage is not the hot-blooded endgame of a level when you understand all its spinning gears. It's the early days where you can easily feel lost and underequipped.

During play, audiences work with minimal health and unwieldy firearms, pressuring them to think through how they tackle tasks instead of rushing in. It's pretty doable to kill an enemy if you have a chance to shoot from a secluded location, training your shot on a stationary target. However, this is not a game where you can stand your ground and kill rooms full of adversaries if they blow your cover. The optimal strategy is to plan ahead so that you don't get caught. If more than a person or two spots you, you'll need to improvise an exit, and getting all of this right requires extensive knowledge of your surroundings.

So, you have a combination of potentially severe punishment for failure, high information density in environments, many goals per level, and a sandbox-like mission format. The designer has a lot to teach the player and must give them a reasonable chance of avoiding or mitigating failure. And they need to do all this without beating the game for the player or watering down the enormous volume of agency the systems lend audiences. As they aid the player, they can't assume too much about the current game state because the openness of the play means that the state can exist in many different configurations. Miraculously, IO Interactive pull it off.

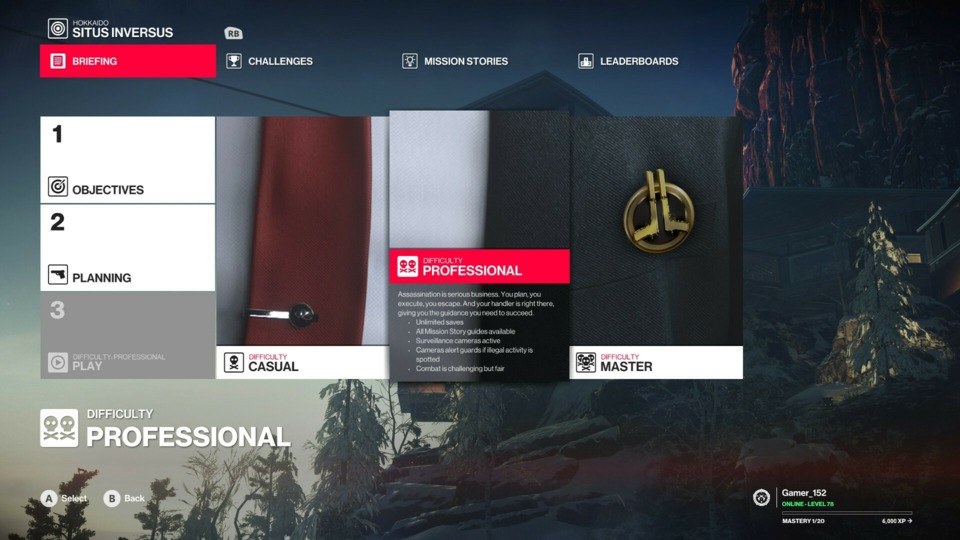

Okay, no more background. The time has come to put Hitman's assists under the microscope. Let's start where any player does, with the difficulty menus. We'll be forgoing the simpler difficulty dichotomy from Hitman (2016) and looking at difficulty in Hitman 2 and III. In the latter two games, there are three explicit difficulty options: "Casual", "Professional", and "Master". Unlike Forza, Hitman does not allow the player to mix and match different aspects of difficulty through these menus. There's no way to move the enemy intelligence up but decrease the number of security cameras. You can't broaden the definition of "legal item" while also reducing your health.

However, Hitman's main difficulty switch is much like Forza's in that it adjusts more than just health and AI competency. Also, in that its UI spells out what's happening under the hood when you select any one option. For example, the description for "Professional" in Hitman 2 reads as follows:

Unlimited saves.

All Mission Story Guides available.

Surveillance cameras active.

Cameras alert guards if illegal activity is spotted.

Combat is challenging but fair.

The same screen describes the "Master" difficulty with this set of bullet points:

One save per mission.

No Mission Story guides available.

Extra surveillance cameras.

Extra enforcers.

Ruthless and demanding combat.

Bloody eliminations ruin disguises.

NPCs are more attentive to sounds.

Specificity in the presentation of the settings allows for intentionality on the part of the player. If, for example, you're having trouble with the number of guards on a map, but you don't know that reducing the difficulty reduces the number of enforcers, then you're limited in your ability to solve that problem. It's the same if you want to turn off the temptation to save but aren't aware that "Master" lets you do that. Hitman's forthcoming approach to difficulty means you understand what each option implies. However, the menu which calls itself "Difficulty" is, in truth, only one of the difficulty menus. I mean, we could say that the map you pick is also a kind of difficulty setting: some are less forgiving than others and emphasise different kinds of challenge, but closer to the explicit difficulty menu, we have the Planning menu.

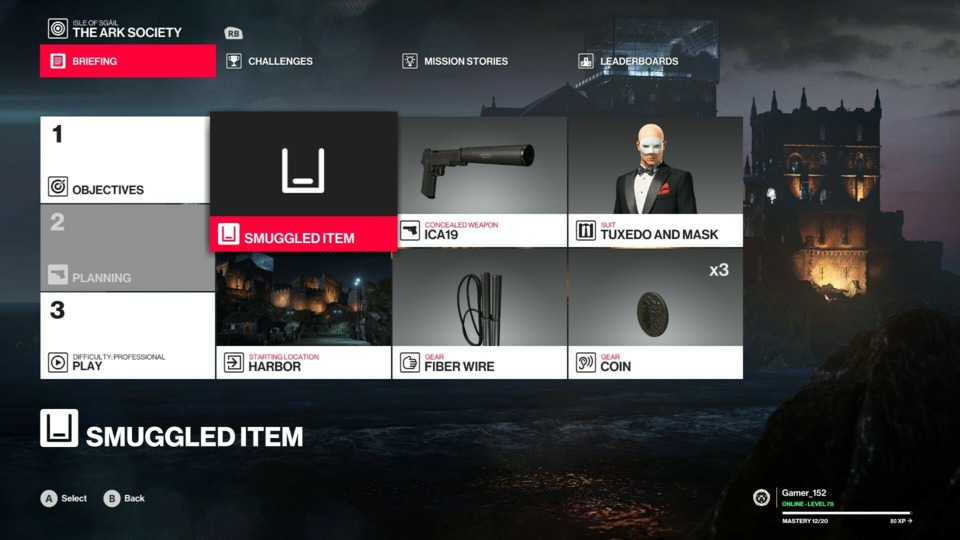

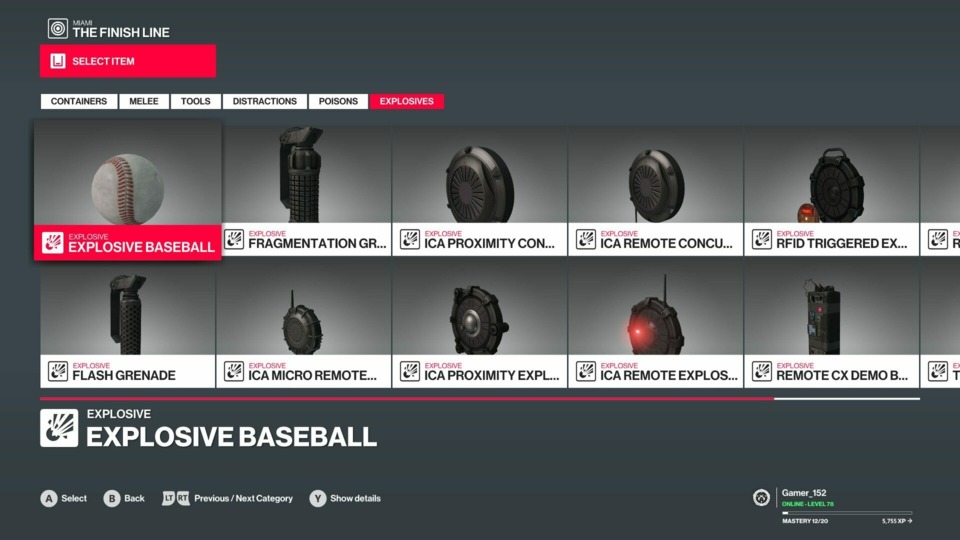

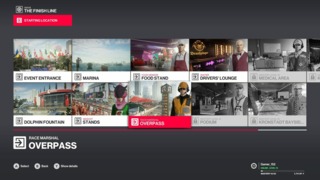

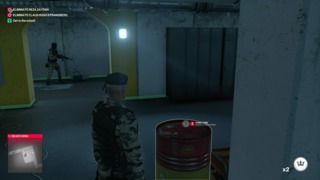

While Hitman's overt difficulty buttons lack the modularity of Forza's difficulty sliders, modular customisation is present in Hitman's Planning menu. Here, the player can decide where in the level they initially spawn, what costume they spawn with, and which items they carry in. Items include weapons, lockpicks, and distraction aids. These objects empower the player to carry out directly beneficial tasks in a level (usually killing a target or achieving a Challenge). Alternatively, items let them take an action that gets them closer to fulfilling such goals (e.g. Knocking out a bodyguard, fetching a weapon, or infiltrating a target's base).

Certain areas contain certain items and targets, and designated costumes open up access to corresponding areas. E.g. A waiter's uniform would grant you entry to a kitchen, or a lab coat would allow you into a laboratory. So, when the player picks their starting location, outfit, and gear, they're exercising agency over how a session will challenge them. Their choices in that regard can play into or against their skillsets and knowledge, allowing for that lock-and-key approach to competencies and difficulties that we're looking for.

Requisitioning mines for a level will make more sense for a player who is better at manipulating NPCs into clinch points on the map. Bringing in a sniper rifle will be preferable for assassins with good aim. If the player wants somewhere to use their sniper, they may choose to spawn near a vantage point in the level, while someone more confident at sneaking into a target's stronghold may pop in in a regularly patrolled basement.

Part of what's ingenious about Hitman's difficulty systems is that IOI makes adjusting the difficulty not a boring perusal of abstract UI elements but a hard-boiled exercise of choosing the right spy gear from the table. Poring over screens of garotte wires and remote explosives, you feel like the titular Agent 47. Moreover, the process of selecting equipment is a rush because each tool brings the promise of cutting down enemies and opening up levels in spectacular new ways. You dream about how you're going to sneak through that mansion with the hacking tool or make an idiot out of a gunman with the explosive rubber duck.

One last manner in which Hitman's difficulty menus align with Forza's is in the developer presenting them at the start of every mission/race. Hitman suggests you alter the difficulty at the beginning of a run with a few different nudges:

- Your cutscene briefings often end with your handler telling you to "prepare".

- The Planning stage is framed as something you should do before a mission by virtue of it being called "Planning".

- The Objectives, Planning, and Difficulty buttons are labelled 1, 2, and 3, suggesting that you should decide what difficulty to play and what your abilities will be before you enter the level.

- The game does not remember your setups from previous playthroughs, meaning you must plug them in each time.

Again, difficulty is treated as something that applies only to the next play session and altering the difficulty is normalised. It encourages the audience to experiment with different difficulty setups, potentially growing their abilities. So, the player has donned their best disguise and filled their suit with only the most advanced spy gadgets. What does it look like when these objects interact with the fabric of the levels?

In comparison to Forza's difficulty menus, Hitman's don't let us alter as much about the play. However, Hitman compensates for that lack of malleability in the setup phase by giving us radical agency during live play. Hitman is not the linear track of Motorsport or even the branching tunnels of most modern single-player experiences. Every inch of every map is querying the player about which choice, of many, they'd like to take. This is one way in which the game gently handles modular difficulty without the use of any switches or sliders.

Players can decide how much risk they take on by choosing how close they get to enemies or how publicly they commit illegal acts like stealing. They can select the kind of play that bests suits their skills by, for example, approaching challenges with firearms or more discrete kill methods. They can attempt to slip through an area by sticking to the shadows or observing NPCs' social patterns and stealing the right costume to go by unnoticed. Within these categories, audiences have many sub-choices. What routes do they carve out? Where do they stand when they fire their guns? What costumes do they wear? Over time, they can form and revise preferred methods for overcoming each obstacle based on their experiences.

So, how does the game educate the player about their options within this arboreously branching space? And how does it do it without spoonfeeding them answers and interrupting the development of their skill? Hitman's levels have four means of signalling possible assassination possibilities or tricks to get closer to our targets:

- Characters on the map gossiping about ways to manipulate marks.

- NPCs wandering into our view wearing clothing we could steal.

- Essential tools strewn about the map.

- Scattered documents providing intel on the level.

- Characters entering areas of the environment in which they are vulnerable, e.g. Standing at the edge of a high ledge.

It is not enough for the levels to simply implement these methods in isolation. Instead, they work because the designers carefully plan out which paths lead us to which clues. Let's take the first two assignments from Hitman (2016): Guided Training and Freeform Training. The setting for these missions is a wooden reconstruction of a cruise ship hosting a lively party. When we first play this level, we can see cocky high-roller, Terry Norfolk, leaning against a car. In the distance, there is a gangway that provides entry to the ship, but as two guards flank it, we can't just stroll onto the vessel.

The tutorial has us steal a mechanic's costume and enter the ship through a service entrance. In front of us is a door, but instead of telling us to open it, the prompts instruct us to climb the stairs to our right. Above, we steal a crewmember's uniform and tend bar while our target, Kalvin Ritter, monologues. Ritter then takes a swig of wine and enters a private meeting with Norfolk. We sneak in through a window, clip Ritter the head, and beat a fast retreat.

After completing the map under strict command, the game invites us to beat it however we want. As the guided route had us pass by various level elements but not engage with them, it naturally draws us to investigate them on additional passes. Now knowing that Norfolk meets Ritter in seclusion, we could take some coins from near our spawn location early table, throw them on the ground to lure Norfolk away from his car, knock him out, and put on his clothes. With his suit, we could pass all the guards to meet with Ritter, who we then assassinate. Or, what if, after entering through the side passage, we walk through that closed door we didn't check out? On the other side is a vial of rat poison. We can steal that, and knowing when and where Ritter takes a drink of wine, slip it into his glass beforehand. When he heads to the bathroom to purge the poison, we drown him in the toilet.

Let's look at the same suggestive environmental design in the game's fifth mission, The World of Tomorrow. Here, we can concoct a toxic meal in the kitchen and ring a bell in the yard outside. The bell calls target Silvio Caruso to the table, where he will eat the dodgy dinner. He begins throwing up over the side of a balcony, providing us with the perfect opportunity to kick him over the edge. That is, it would be perfect if it weren't for the enforcer standing between Caruso and us. The easiest solution is to run around to the other side of the building to bypass the guard. When we do, we slip by two slacking workers deep in conversation, an unlocked door, and an open entranceway with a gramophone inside.

A player returning to this stage now knows they can stop and listen to those staff on break. If they do, they'll hear that Caruso is obsessed with a gramophone owned by his late mother. Sure enough, we can use the record player as another form of bait to lure him into the open. If we head through the unlocked door, we enter the hidden love nest of our second target, Francesca De Santis. We can pose as De Santis's secret boyfriend, seducing her into that nook and using that opportunity to kill her. We may even notice that the yard we start from in this mission has a direct view of a church tower across the way. We might realise we don't have to make Caruso sick at all; we can just prepare his meal, climb the tower with a sniper rifle, and take him out from the church. These scenarios cover only one tiny corner of The World of Tomorrow.

You can see how taking any route through a Hitman mission raises your awareness of alternate routes. Walking those alternate paths can teach you about other dynamics in the environment, and so on. The knowledge that the player gains from this exploration lets them better match the shape of a run to their talents. Someone who knows about the stairs and rat poison routes in the training map can implicitly make a choice about which best matches their skills and their desire to test those skills. The same is true of a player who knows about the gramophone and church areas in The World of Tomorrow.

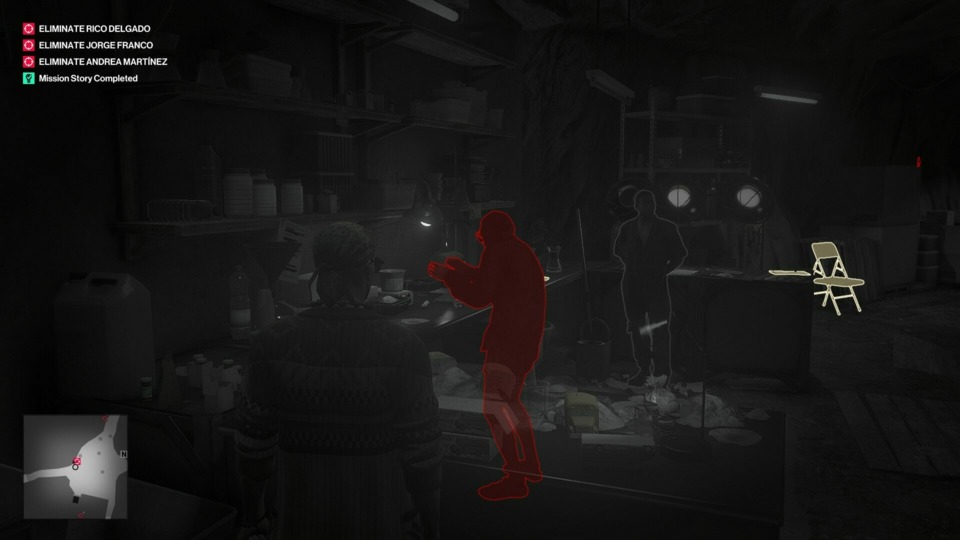

Another crucial tutor for the up-and-coming assassin is the Mission Stories system (known as Opportunities in Hitman (2016)). This is the series' equivalent of the Driving Line: a series of arrows telling you where to go but leaving the tasks at your destinations up to you to perform. Each Mission Story consists of a sequence of steps the player can take to line them up for a particular murder method on a given target. When the player activates a Mission Story, a lightbulb icon appears over a character or object on the map, and the player receives a text prompt telling them how they must interact with it or them. For example, "Get the Helmut Kruger disguise" or "Find Florida Man's key". When they complete these directives, they get another instruction, e.g. "Call Margolis" or "Find a crowbar". These chains of objectives continue right up to the point that the player is standing before one of their targets, ready to execute them.

These exercises fill in some gaps in the player's knowledge while still forcing them to close others through their own deduction. Even with the help of a Mission Story, the player often has to reason when in their activity cycle NPCs are most vulnerable, where the best spots to hide bodies are, or where bystanders might witness their crimes. Where Mission Stories do educate players, they do it on a few different levels: At the surface layer, players learn from Mission Stories where to find costumes and other items to manipulate strangers in future missions. In 15 Seconds of Fame, a Mission Story from Hitman (2016)'s The Showstopper, we pick up that we can use Helmut Krueger's costume to get behind the scenes at the fashion show. The Munchies Story from Hitman 2's The Finish Line teaches us where we can pick up the key to open the Miami map's food stand.

On a slightly more subtle level, Mission Stories can teach players general patterns that they can exploit across most missions and increase their confidence in carrying out those exploitations. In 15 Seconds of Fame, the player learns that targets may be willing to meet them without a bodyguard if they're dressed as a close associate. Sure enough, within the same mission, although not in this Mission Story, the player can kill Dalia Margolis by meeting her dressed as a wealthy sheikh. In The Munchies, the player crowbars open a seaside shack and retrieves a food stand key from inside. This teaches players that they can open locked doors noisily, by force, or quietly, with keys, but that keys tend to be hidden and slightly challenging to obtain.

On the most indirect level, Mission Stories drag players past items and landmarks that suggest possibilities. To reach Helmut Krueger, we must stroll through the mansion's bar, where there's ample opportunity to poison someone's drink. We must also walk past the lawn on which there's a helicopter parked that we can use to exit after our dirty deeds, and we dispatch Krueger close to a garden shed full of dangerous tools we could use for all sorts of mischief.

In The Munchies, the shack we break into contains a key to a level exit. And while, during this story, we inject an emetic into a meatball that our target (Robert Knox) then eats, there's also the possibility of returning on another pass and injecting the meat with lethal poison. We may also see Knox look out from his balcony to check whether the food truck is serving. In this moment, he leaves himself vulnerable to being sniped from the bay.

On top of the Mission Stories, various other teachers help the player fill in their understanding of the stages outside of their immediate cone of vision:

- "Instinct" lets us view NPCs and objects through walls and highlights interactibles, targets, and enemies that will see through our disguise.

- Text popups appear on-screen when witnesses get suspicious, when belligerents begin hunting us, or for other noteworthy occurrences.

- The minimap lets us view enemies and architecture around us, including NPCs that may see through our disguise.

- Labels bordering the minimap provide some information about our current state, e.g. That enemies are searching for a suspect or that they're hunting us.

- Enemies vocalise when they see something that spooks them.

- If we venture close to an enemy that can blow our disguise, an arrow appears. It shows the direction they're standing in relation to us and fills to indicate how close they are to sussing us out.

Stealth games often get so married to realistic representation that they don't incorporate these more "gamey" UI aids. And what's particularly smart about Hitman's approach to them is that it turns many of them off on its Master difficulty, encouraging the player to use them as stabilisers during training but ultimately pressing them to perform without them.

Hitman's level design is second to none. I could happily spend a year's worth of articles disassembling it. However, we can infer from the above analysis that it's not the level design alone that allows Hitman to retain its highly open but educational nature. Instead, the developers combine Mission Stories, UI, and level design to keep us aware of our current performance while informing us of alternative approaches. Despite Hitman constantly feeding us information on the play, we retain the sense that we are the ones doing the instrumental work to achieve our goals. This is because it's mostly us who puts the various data streams together and acts on them. However, there is one more ingredient in the pot that creates that effect.

In the first article of this series, I mentioned that solving puzzles in text adventures can feel unfair because they don't always tell us which actions our character can perform. We can't master tools if we don't know what the tools are. Challenges are one way that Hitman prevents the same ambiguity arising in its play. If there's a Challenge to drop a stalactite on our target, then implicitly, we know that's something you can do in the level. If there is a Challenge for solving a chess puzzle, then you know that's possible.

Not all Challenges lead directly to a solution for the mission: some simply reward us for exploration, but exploration develops our knowledge of the map, helping us toward mastery. Some Challenges also reward us for carrying out deliberately contrived tasks like feeding all the targets in an environment to a hippo or finishing a stage without donning a disguise. It's relatively obvious how such actvities grow our skills. Lastly, there are a few exceptional Challenges that have their text "redacted". We must extrapolate their objective from their name, picture, and what we know about the level, forcing us to pay particular attention to our environment and its contents.

Let's return to a couple of issues that occur in Forza Motorsport 6. Firstly, players of Motorsport 6 had limited incentive to keep turning up the difficulty past a certain notch. This was because the extrinsic motivations for doing so were rewards that mostly translated into new vehicles. So, once you'd gotten a few fast-as-lightning cars in your garage, why would you keep making the game harder for yourself? What goods would you gain from doing so? Secondly, Forza's "Mod" system pushed players to impose new handicaps on themselves. However, once the player found a Crew Mod that would provide their optimal ratio of rewards to disadvantages, there was diminished encouragement for them to try and change up their playstyle.

Hitman shows a superior approach to tempting audiences into developing their talents. Players unlock new starting locations, gear, and costumes as they gain experience points, and Challenges are, by far, where there's the most experience to be won. So, how does the game prevent you from unlocking the slickest spy equipment and then ignoring the Challenges from there? Hitman subverts this problem by making Challenges, and many of the rewards for beating them, level-specific.

To tick off the challenge Tunnel Vision in Hitman (2016)'s The Gilded Cage, we must kill Reza Zaydan in the tunnel with an exploding oil drum. Achieving Stand Still in Hitman 2's Chasing a Ghost means assassinating Vanya Shah with a tape measure while dressed as a tailor. And challenges like killing all targets while wearing a suit or poisoning our prey to death, we must unlock per level. Therefore, there's no getting around developing various new skills and learning each map if we want to max out our level on each stage.

On the other end, suppose I am playing Hitman III, and I earn enough experience to open up a new starting location or hidden stash in Dartmoor. Those advantages don't carry over to any other level. I couldn't just get good at playing Dartmoor, neglect growing my skills on any other stages, and waltz through them with my cool new toys. For any and all environments, I must win my rewards in them by demonstrating skills at them. This creates a feedback loop in which we receive new starting locations and items to use in a level, we put them into practice, and in doing so, improve our skills at that one stage. When we become more talented at manipulating a map, we can achieve better results in it, unlocking more elements to use, and round it goes.

Further, this level-specific reward scheme lends the designers plenty of control over our learning experience. They can ensure that we do not start deep into a level with a disguise that opens all doors. Instead, we must learn and demonstrate knowledge of the basics of the map before we can skip ourselves past the chance to dial in that fundamental understanding.

In essence, Hitman's rewards motivate players better than Motorsport 6's because Motorsport 6's rewards are fungible, whereas Hitman's are largely unique. In Forza, one pile of cash is as good as another, so once you have enough cash, why keep bumping up the difficulty? In Hitman, rewards often cannot be replaced with each other, so even after you've made considerable headway in a stage or the game overall, there's still a reason to test your mettle at all sorts of new tasks. And the Challenge system is pretty flexible too.

Note that by awarding XP for a wide range of different objectives within any one level, Hitman initially moulds itself to the player's talents. Whatever activities within the game the player is best at, they'll find Challenges to accommodate. But the more they play a mission, the more easy Challenges they clear. So, they must move ever further outside their comfort zone to keep earning experience.

In all cases, the player can experiment with new approaches without fear of throwing away a whole level's worth of progress. It is possible via the game's save game options, Hitman's answer to Forza's Rewind. On the Casual and Professional difficulties, the player may save and reload their game at any time. Like Forza's Rewind, Hitman's saves encourage players still studying the game to play it risky and find out what they can get away with. If anything goes catastrophically wrong, they can turn back the clock. However, it's not just the existence of this mechanic that allows the player to rehearse and revise; the implementation is everything.

To start, note that the Save Button is the first option on the game's Pause Menu, while the Load is the second. In four quick button presses (On the PlayStation: Start, X, X, X), the player can create a suspend point, and in just five (Start, Down, X, X, X) can load from that checkpoint. The save menu allows us to identify, at a glance, where we made each of our saves and in what order. It does this by pairing them with a thumbnail and identifying timestamp. On a nominally powerful system, accessing menus and saving the game are both near-instantaneous processes, and load speeds are comparatively brisk. If it were time-consuming to save and load, the player would not readily use this system, and so, wouldn't frequently experiment.

Secondly, note how the Save Menu encourages the player to keep multiple restore points. The UI presents many autosaves and manual saves together on the same screen, with save slots just one press of the D-Pad away from each other. Individual mission attempts in Hitman are typically longer than races in Forza. Forza allows the player to mould the difficulty between play sessions; in Hitman, they must make many of the same choices during sessions. This means that while Forza is more suited to a linear mode of time travel to help players practice, Hitman is more suited to a branching time travel system.

To get a picture of how time travel works in Hitman, consider this example: I may reach a fork in my career where I could choose to find some poison, drizzle it into a victim's drink, and try and trick them into ingesting it. Else, I might be able to fetch a screwdriver, sabotage a machine to make it explosive, and coax my target near it. Let us imagine that I take the poison route rather than the machine route, and when I decide to, I make a save so that I may return to this moment if things go awry. I may then successfully obtain the poison but be unsure that I can pour it into my foe's drink without being seen, so I make another save just in case. Then, as I am spiking their drink, a nearby staff member spots me and runs to alert a guard, so I make a third save and run after them, attempting to silence them before they can get help. However, I end up with a bullet in the head and a "Game Over" screen on my monitor.

In this scenario, if I only had a single save slot, I could only reset to when the staff member was about to cry for help, and that might be a sticky jam to get out of. A Rewind mechanic could help me roll back when I decided to poison my target, but rewinding a whole ten or fifteen minutes would be exhausting. With the multiple save system, I can choose one of three save points to regress to. This is useful because I now have a clearer idea of how things will turn out if I pursue my poison strategy and when in the sequence of events my prospects are likely to dip. As in Forza, this Rewind system cannot perform the tasks for me, but it does provide a quick doover meaning the gap between learning from a mistake and putting that learning into action is as small as possible.

And that's it. That's the totality of the mechanics that Hitman uses to help the player toward mastery of its systems. As we did with Forza, let's look at the principles we wanted to see represented and the mechanics from this game that implemented them.

| Principles | Mechanics |

|---|---|

| Making a difficulty system that accounts for the player having different skill levels at different activities. | Variety of methods to progress through levels. |

| Incentivising the player to take on more difficult tasks. | Unlocking new items, XP rewards, Challenges. |

| Giving the player a safe space in which to experiment with the mechanics and interface. | Save system. |

| Allowing the player to practice the same tasks repeatedly. | Save system. |

| Letting the player adjust the difficulty of the game on the fly as they acclimate to the game. | Difficulty prompts at the start of each mission, levels having exceptional variation in how you tackle problems. |

| Giving the player a clear idea of the actions they need to take to succeed. | Level design that teaches you where items are, Mission Briefings, Mission Stories, Minimap, Instinct, Challenges, conversations, documents. |

| Affording the player clear, immediate feedback about the quality of their performance. | Popups on screen that tell the player about changes in the level state, level state listed above Minimap, NPCs vocal about their perceptions of you, Suspicion Indicator. |

| Ensuring the player has a clear idea of alternatives to their current approach, especially when failing. | Mission Stories, level layout, Challenges, documents, conversations. |

Hitman is a game nothing like Forza and yet relies on the same fundamental principles of challenge. It works with the player to grow their skill rather than just lowering the difficulty bar or leaving the player floundering below it. While Forza primarily uses explicit difficulty options to let the player tune challenge, Hitman uses a combination of implicit and explicit. By growing the player's talents on both fronts, audiences can achieve an empowering sense of mastery. Thanks for reading.