Being Watched I: Surveillance in Her Story

By gamer_152 0 Comments

Note: This article contains major spoilers for Her Story and Telling Lies and minor spoilers for Rashomon.

As a rule, surveillance is invasive. It doesn't feel like it should be because surveillance is observation, and what could be more passive than sitting and watching? Yet, the activity typically involves inserting yourself into a social context you were not invited into. For example, using security cameras to force yourself into a workplace or onto a high street, or corraling subjects into a location like a police station or a security checkpoint. You then extract information that targets haven't chosen to communicate or only surrender under duress. Surveillance hoovers up information as personal as where a person has been, what they're carrying, who they've talked to, what they were saying, and anything else you could log with a recording device. There's a reason that being watched feels like someone's eyes drilling into you.

You're probably reading this from an ostensibly free and democratic country. It is worth considering that it is also probably the case that in your country, the state and private interests routinely record the actions of individuals without their express consent or the decision of the community. Surveillance is almost always thrust upon us. At its extreme, it involves someone interrogating us about the most intimate aspects of our lives or having an undercover spy gather dirt on us. 2015's Her Story and 2019's Telling Lies detail these violations, respectively. Both directed by Sam Barlow, these are also games in which characters try to turn surveillance systems back against the surveiller.

A camera has a definite limit to what it can capture; its dominion stops at the edge of the frame, outside of which it's unable to say anything about the world. Yet, that doesn't mean that when a person or event falls within the frame, we perceive them or it accurately. By obscuring everything beyond its boundary, the camera allows for fiction to be constructed within it. This is neatly summarised in one shot from Telling Lies featuring the character of Max. Max is a camgirl who we first see posing on a plush purple bed flanked by lamps draped in coloured fabric, but this isn't a bedroom. Late in the timeline, Max pulls the camera back from her extravagant furniture to reveal it's a set constructed against one wall of a basement. Outside that fantasy of soft violet, there is a blinding white, undecorated reality. But Max doesn't need to worry about her viewers recoiling from the unsexy truth because she knows where the frame ends. She only needs to worry about what they see inside it.

However, once we've seen outside the frame, we can't recognise anything within it the same. When we subsequently watch scenes of Max sitting on her sheets, sweet-talking customers, we cannot view her as a woman making an honest, romantic connection in her bedroom; we see an actor on a set. To reframe is to recontextualise, and none of Barlow's characters embodies that idea better than Her Story's Hannah. Max is intoxicating a bunch of thirsty guys on the internet, but Hannah is going to do something more dangerous with the camera. She's going to deceive law enforcement.

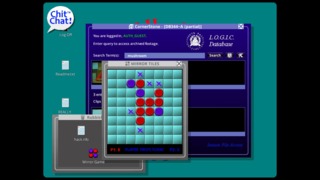

Hannah Smith arrives at a police station in Portsmouth on 18th June 1994 to report her husband, Simon Smith, missing. Soon, it will transpire that Simon is dead and Hannah is the prime suspect in his murder. Beyond that, there's no linear or conclusive plot for Her Story because the game does not have a fixed order in which its scenes occur or a definitive canon. We play a shadow of a protagonist who has elbowed their way into a database of police interviews with Hannah. At least, it always looks like Hannah is the one in the interviews. Our only method of navigating the database is a search engine. On each search, we receive the first five files whose transcript contains the word we've typed into the text field. So, if I type in "parents", I get five videos in which the word "parents" is spoken. We progress by listening to testimony and learning names, places, and other proper nouns which pertain to the investigation, then seeking them out in the files.

Although we don't experience Her Story in chronological order, over its run, Hannah does relay a narrative you can fit to a timeline. After initially protesting her innocence, she describes an identical twin sister called Eve, who may be filling in for her in some interviews. According to her or them, when the sisters were born, a midwife named Florence delivered them. Florence lived in the house opposite Hannah's parents and had seen her husband leave for war. The couple agreed to have a child on his return, but they would never get the chance because he died in action. When Hannah's mother gave birth, it was to twins, but one of them appeared to be stillborn. Florence quickly removed the second child, Eve, leaving their Mum with only Hannah. Unbeknownst to her mother, Eve was still alive.

Florence raised Eve as her own but passed on during her adopted daughter's childhood. Hannah took Eve into her household, where the twins began living a double life under Hannah's identity, a charade they'd keep up well into adulthood without their parents catching on. While one went out into the world, the other would hide in the attic. In their antics, they became obsessed with the story of Rapunzel: the fairy tale in which the blonde princess is trapped in a tower but lets down a rope of her hair for a fair knight to climb. Then, the spiteful Mother Godel cuts off Rapunzel's hair, and the knight plunges to his death.

Eventually, Hannah fell in love with Simon, a glazier who specialises in mirrors. They moved into his family's house, separating the sisters for the first time, which was emotionally agonising for Eve. When Simon and Hannah tried for a baby, Hannah miscarried, and a doctor declared her infertile. Meanwhile, Eve started her own life, disguising herself with a blonde wig, and Simon found her singing at a local bar. The two began an affair, leading to Eve becoming pregnant with a girl she'd later name Sarah. With one twin pregnant and the other apparently unable to conceive, they could no longer pass for each other. Yet, Hannah remained unaware of the affair. The two came clean to Simon, who appeared unconcerned with the contrived tryst he'd found himself in.

When Eve revealed the affair to Hannah, the two had a falling out and Eve drove to Glasgow to get away from the couple. Always the worse motorist of the two, Eve got into a minor car accident in the city, but under the Hannah persona. On Hannah and Simon's eleventh anniversary, Hannah approached Simon, using Eve's wig to disguise herself as her sister. Thinking she was Eve, Simon professed his love to her, gifting her a mirror. Hannah smashed the mirror in a fit of rage and waved a shard of it about in an attempt to scare Simon off. Instead, she slit his throat. When Eve returned to the house, the two agreed to cover up the crime. Hannah went to the police, saying that she didn't know the whereabouts of her husband, with an alibi for his killing: she was in Glasgow at the time of his disappearance. Eve and Hannah believed this excuse, along with Hannah's cooperativeness with the investigation, would exonerate her. At least, that's her story.

Because players uncover footage through word association, each experiences a unique zig-zag through the database. A traditional film can be edited by a creator conscious of pacing and the optimal distribution of information. In Her Story, that role is taken on by your search engine in all its pseudo-random fallibility. The rhythm and novelty of the game suffer for it. I'd sometimes find myself so close to a revelation I could smell it, only to have the excitement extinguished by a bucket of videos re-confirming information I already knew.

Despite its shortcomings, Her Story's search system empowers it to do something no other game did before. It combines its navigation tools with its single-camera cinematography to pull off Max's recontextualisation trick multiple times. It's common for popular fiction to include twists and turns. Still, most storytelling spends more time adding onto what it's already told us than changing our perspective on what we've discovered. When absorbing a story, we expect A to happen, then B, then C, and so on. But Hannah's history is amorphous. We learn of new events, but A is liable not to stay A; it turns into B, and then C, and then D before our very eyes.

For example, near the start of the game, I learned that the police found blonde, synthetic hairs at the murder scene. That evidence suggested to me that Hannah tried to disguise herself when she killed Simon. But then I learned about the existence of Helen, a blonde bartender Simon was infatuated with. Suddenly, I thought there was a strong possibility that she was the culprit, not Hannah. Then, I decided that Helen was a cover identity for Eve, who had been wearing a blonde wig. This pegged Eve as the perpetrator until I heard from her that Hannah was wearing her wig at the time of Simon's murder.

I'll give you another example. Upon seeing the first clip, I did not know whether or not Hannah offed her husband. Then, I learned about her jealousy of Helen and heard about an incident in her childhood in which she held Eve's head underwater. In one excerpt from an interview, Hannah sings a song about one sister killing another, and suddenly, it seemed more likely that I was staring down a murderer. Then, I discovered that it was actually Eve singing the song, that Eve was envious of Hannah's relationship with Simon, and that their parents died of fungus poisoning when Eve was in the house, even though her father was a mushroom expert. After that, it felt much more likely that Eve was the villain, before my perspective switched once more upon Eve telling the camera that Hannah swung the blade that killed her husband.

You can access scenes late in the game's chronology from the start, but you can't spoil it as we'd conventionally think of spoiling. Because, at the beginning of the game, we don't have the necessary context to interpret those final scenes. Her Story makes certainty shortlived, and Rashomon-style eschews the idea of a fixed history. That might seem like an act it can't keep up forever because, eventually, a player has to have viewed all of the clips and composed the entire timeline. Yet, while you can watch more videos to build a fuller picture of Hannah's version of events, that same process can erode trust in Hannah.

At times, she appears to slip up and forget she's meant to have a sister before correcting herself. And Hannah's account is incredibly far-fetched. Eve's adoptive mother managed to kidnap a child from the hospital and raise it as her own without anyone stepping in. She happened to bring up Eve in the house opposite her identical twin. Then Eve and Hannah lived a double life so successfully that Hannah's parents didn't notice that their daughter kept swapping out for a clone or that a girl was living in their attic for years. The twins also manage to live out the plot of Rapunzel after being obsessed with it as children: The dark-haired woman takes the light-haired woman's locks and murders the man smitten with her. Eve(?) ends her last interview by labelling everything she told the police as "just stories". Her ostensible confessions feel like a continuation of her childhood obsession with fairy tales.

But if this story is a fabrication, is that deliberate on Hannah's part, or does she have an alternate personality? Was there ever an Eve, and if so, did Hannah drown her? And if Hannah's story is inaccurate, then what bits of it? And what about the evidence for Hannah's version of events? Simon appeared to be murdered when "Eve" was in Glasgow. There was another set of prints besides Hannah's at the scene. We can see Eve has a tattoo Hannah doesn't. And there are counterarguments to these points and counterarguments to those counterarguments, and so on. However, there is no version of events in which Hannah doesn't manipulate the viewer and create significant confusion about the case.

One constant in the game is a reflection of the viewer in the in-world PC monitor. Their image becomes more pronounced in the moments after they dig up vital information. The game is wall-to-wall mirror metaphors, to the point it gets patronising. Hannah calls Eve her "reflection", her husband is a mirror-maker killed with a shard of one of his creations, Hannah and Eve's names are palindromes, the time-waster on the computer is called "Mirror Game", etc.

These references foreshadow the viewer character being ripped from the drama on screen: exhaust the database, and you'll find out that you've been playing a present-day Sarah, Eve's (or Hannah's) daughter. But the mention of mirrors also speaks to the interaction between you and the videos. There is not an airtight wall between the audience and the footage. After all, people perform surveillance so that anyone accessing the collected data can assimilate it into their understanding of the world. Some part of the data becomes part of you. But then we also process future data based on what data we've already read, and that material we've read can be unreliable. A general lack of context or outright duplicity on Hannah's part warps how we see the other clips in the database, potentially leading to a cascade of misunderstandings.

The term "video evidence" has become synonymous with incontrovertible proof in legal cases. It's the detail inherent in the medium that makes it ubiquitous in modern surveillance. In Her Story, the police attempt to drag a suspect's marriage, sex life, work, travel, home, family and childhood kicking and screaming in front of the probing gaze of the all-seeing camera. But still, Her Story's filthy CRT remains an imperfect mirror of reality. Literally and via the game's graphics, it shows that we project onto film as much as we study from it. And it's all because of where the monitor ends.

If we could see into Hannah and Eve's attic as they grew up or the Smith home at the time of the murder, there'd be no open questions, but the whole database is a camera pointed at a woman in one of two interview rooms. That leaves the rest of the world as a big, fat question mark, and that's why Her Story works as a mystery game. This myopia is also what allows Hannah to tell such colourful stories about her life. We have very little world to check them against. The game does not preclude the possibility of more expansive surveillance or of attaining objectively accurate information from footage. What it does is suggest both that the video evidence the state leverages against a person can be misleading and also that the limitations of surveillance might be limitations of the state. Thanks for reading.