More Narrative-centric Games

By gamer_152 15 Comments

A little while back I blogged about the unification of gameplay and narrative in games and gave a couple of examples of it working well and a couple of examples of it working not so well. I know that some found those pieces a little heavily influenced by Jonathan Blow, but to show that it’s not just his games and examples that reflect how narrative can work via game mechanics I’ve come up with three very different types of games which make the player feel the emotions of their stories through their gameplay. I hope you enjoy.

The Marriage and Passage

Indie developer Rod Humble’s game, The Marriage, was his attempt to create a video game that qualified as art, however whether you perceive it as art or not, one is undeniable about the game, it tells its story through gameplay. You can download the game for free here and you’ll find a piece on the same page Humble has written about the true meaning behind The Marriage, but I implore you to try and interpret the game for yourself, as decoding the meaning behind his work is one of the most enjoyable parts of the game. One of the greatest strengths of The Marriage is its ability to do so much with so little, the game is an absolutely minimalist affair, consisting of a few simple squares and circles, and yet of out the size and movement of these shapes a simple story is built where you actually care, at least a little, about the characters they represent, because they’re important to the gameplay.

Jason Rohrer’s indie title Passage is another independently developed game that uses its gameplay to get its point across, however unlike Humble’s game, it focuses primarily around the concepts of life and mortality. You can tell right from the start that it carries out this exposition in a very different way too. You can download the game free at this link and read a little about what Rohrer is trying to do at this link, but again a large amount of the fun is about discovering what the game is about for yourself.

In general while I think these games are very inventive it must be admitted that they’re very basic games. They’re dealing with largely uncharted territory though so it’s only to be expected that they’re starting off small. Are these the kinds of games that I think will become the norm in the future? No. While they display the power of gameplay as a storytelling tool they require a certain amount of analysis and translation to understand, and that’s not what the general public want, for what they are though they’re a promising indication of video games abilities to tell stories.

Train

So here’s a game that’s loud and clear about what it’s doing, albeit a board game. You may be wondering whether we can really learn about video games through board games and the answer is not only “yes” but that video game designers have been doing it for years. While it may seem a little reductionist, once you strip away the aesthetics and the essential technology used to deliver the experience what you have is a set of rules or gameplay mechanics, and so on that level all games are comparable.

You may have heard about Train if you have listened to Giant Bomb’s GDC Bombcasts, but in case you haven’t Train is just one in Brenda Brathwaite’s ‘The Mechanic is the Message’ series of games. Brathwaite started working in the video games industry over thirty years ago and is responsible for the Wizardry series and the Jagged Alliance series among other games. You may not think that her development credits sound particularly impressive but as was the case with Jonathan Blow it’s not just important what the person has created here but what they understand about video games.

Train is a two player game where, on their respective turns, each player rolls a dice and decides whether to move their train cart forwards by the number shown on the dice or add as many people (which are physical pieces in the game) to their train cart as shown on the dice. The object of the game for each player is to deliver their passengers to the end of the train journey. Special event cards which change the course of the game can be picked up along the way but ultimately what matters is the “terminus card” that is turned over when the first train cart reaches its destination. This card bears the name of a Nazi concentration camp and this is the point at which it is revealed to the players that they have been playing Nazi officers packing Jews into train carts and sending them to their death. At this point the players can decide to get up and walk away, having nothing to do with the grim business anymore or they can continue to keep playing, attempting to sabotage the operations.

Undoubtedly just by touching on such a sensitive issue it’s clear that Brathwaite’s game was poised to invoke emotions in many but I think the fact that it is a game and not just a book, film, or other piece of work is integral to the experience it has provided players. Brathwaite says that due to the game being about the players personally handling the people and moving the carts it couldn’t work as a video game, and I see her point, but none the less it shows the amazing power that interaction can have in telling a story. These past few examples have all been fairly niche games though, perhaps we should look to an example of a more mainstream game.

Missile Command

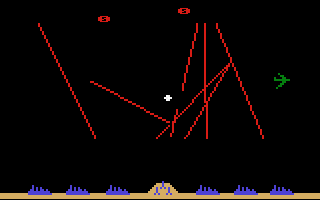

Kudos for coming up with this final example actually go to The Escapist’s illustrious Extra Credits crew. In their episode on ‘Narrative Mechanics’ they note that despite being a game originating from the halcyon days of the arcade it manages to use it’s gameplay to make you really feel a tiny piece of the stress and struggle of defending against a nuclear attack. Some might assume that because Missile Command doesn’t lay out its narrative through explicit text or cinematics that it has no narrative but remember, a narrative isn’t necessarily a clearly laid-out or highly involved story, as The Marriage showed narrative can be born out of something as simple as the most basic graphics of a game.

In Missile Command the narrative consists of you are defending six cities against a nuclear strike using three missile launch sites, nothing more, nothing less. The game manages to make you care about the cities, not through a grand story of terrified citizens awaiting the inevitable end, or cutscenes of women and children huddling together in their last moments, but by making the cities the only thing in the game standing between you and failure. As a player your number one priority is to keep those cities standing and because they matter to you as gameplay components, they matter to you on an emotional level. I believe there’s a lot modern designers can learn from a game like Missile Command.

Duder, It’s Over

So, there are a few more examples of games that able to use their gameplay as a tool for their narrative, rather than leaving the story and gameplay as largely unrelated components, and I really hope we can see more of the like in the future. Thanks for reading. Good luck, have abominations.

-Gamer_152