Some things age badly – 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand is not one of them

By MMMman 0 Comments

This piece skips happily down the road with this piece, try and read them both if you have the time.

Everything ages and eventually slips into obscurity, such is life. My parents are getting older; my father’s once magnificent ginger moustache has been steadily greying for the last half decade and now resembles an ageing cathode ray television; still full of energy but not all the glorious colour of the past. It is still a pretty magnificent moustache though, all the same. My grandmother, in her mid-seventies, has recently moved from the home she shared with my late grandfather as it was simply too large for her to live in alone. Did she go straight to a nursing home, away from the bright lights of society and all its moustachioed inhabitants? No, of course not, she moved to a one bedroom ground floor flat on a cul-de-sac where a few of her friends already reside. Living there makes it easier for her to go dancing, play whist, console and inspire recently bereaved local residents, go walking in the country and partake in the numerous other activities she now fills her time with.

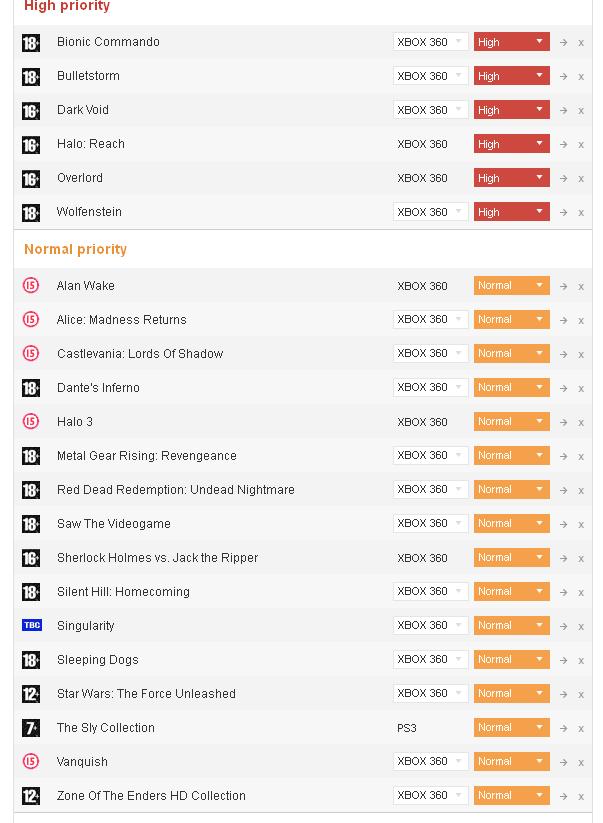

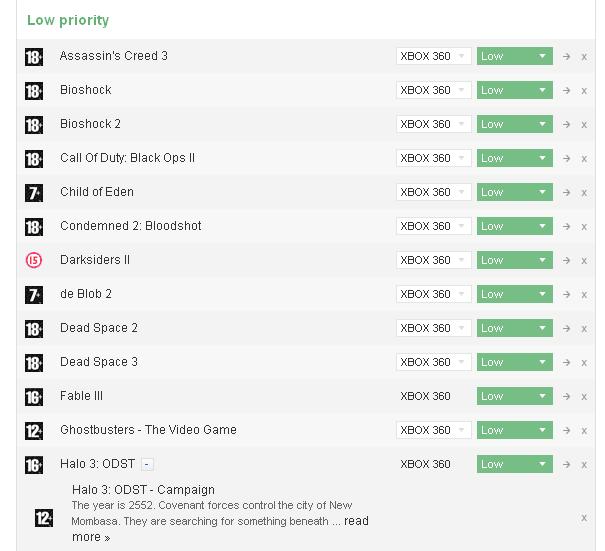

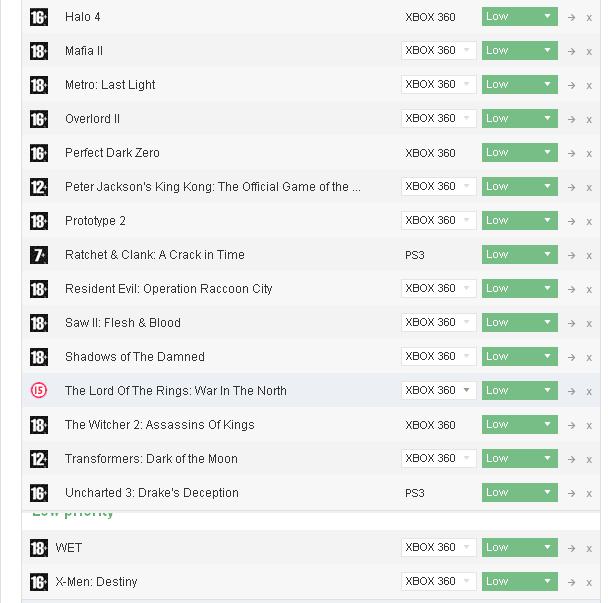

Ageing games, just like ageing people, shouldn’t be put out to pasture once they are perceived to be past their prime. Alliteration aside, I feel that as a community, we who play games are often too quick to become diverted by whatever shiny new distraction we are presented with. Granted, video games are inherently a form of entertainment driven by technology and its advancement, but there is a difference between embracing something and becoming preoccupied by it. Too much of this year, at least for me personally, has already been given over to speculation about, and more recently condemnation of, new consoles and their feature sets. I shan’t be buying a new console until I’ve mined everything I can from my current boxes, for there are many experiences I’ve yet to have. In six months time these quickly ageing games may seem damn near antiquated in comparison to the fireworks and gin martinis available on ‘the new consoles’, but they are still games that need playing. And besides, I’m sure someone cared about them once upon a time.

Not all of these games will be great I’m sure, and I’m fully expecting that some of the titles I’ve got my eye on will be time and again tiresome wastes of time. There’s Wet, Saw and Silent Hill: Homecoming that I assume will be nothing more than derivatives of more accomplished products. Alice: Madness Returns and Alpha Protocol that will more than likely be a tad unpolished and clumsy, but no less interesting for it. Then come the unnecessary and tired sequels; Assassin’s Creed III, Dead Space 3 and Fable III, all games that I imagine will prove the time-tested rule that everything becomes mundane if you keep doing it for long enough. Some games, however, will be good, very good. The laws of mathematics and science dictate that for every dung pile of terrible, or boring, or broken, or infuriating games, one saviour will rise through the swampy mess of mediocrity, floating on the sweet smells of levity and mixed metaphors to reinstill our collective faith in video games. Once such demigod is 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand. We got there in the end.

50 Cent BotS is at the most basic level a cover shooter that incorporates score-attack by way of a kill multiplier system. Kill a bad guy and you get some points. Shoot him in the head to get more points. Shoot another bad guy in the head and you get some points and all your points are multiplied by two. Shoot another bad guy in the head and you get some more points and all your points are multiplied by three. Shoot another guy – you get the idea. As long as you can keep shooting guys in the head quickly enough – or setting them on fire, or blowing them up, or stabbing them to death – you’ll keep earning points for our 50. And he does love those points. Like any successful entrepreneur he is constantly pushing himself, the surest road to success, and uses his accumulated points to assess his productivity and ongoing social relevance. I wasn’t very good at boosting his ego and consistently scored mediocre bronze scores; something I felt really hit him hard. He seemed to always be angry, as if by us underachieving we were somehow failing altogether, even though we were mowing down all the greedy and evil A-rabs who stole his money and blowing up all the H-elicopters that helped them do it.

Though maybe it was this very anger that helped him forge ever forwards, through the tyranny and deceit that surrounded him. The game opens with 50 being double crossed and robbed, something so despicable I had to punch a wall for five minutes after I’d witnessed it, and left for dead (a bit, anyway) on the roadside. After this unforgivable affront to his person 50 vows to clean the world of the morally bankrupt, swearing there and then that anyone who employs lies to deceive good people will be smite by his hand in the very spot they stand. Surprisingly, every single non-G Unit character 50 subsequently meets along his upstanding crusade decides to not heed his warning, attempting to double-cross the good man at every turn.

He sees through these ploys instantly on every occasion, though often plays along with the deception until the villain sees fit to reveal themselves, even going as far as feigning surprise when the truth becomes apparent. He is never, I must stress, actually taken by surprise; 50 is far too intelligent for that to happen. It is his straight and true attitude to the events that unfold around him that I see as BotS’s strongest element. In 50 we are presented with a no-nonsense lead who simply wants what has been stolen from him; a rare example of unselfish motivation in the action genre, which is usually played from the perspective of a thief (Uncharted, Tomb Raider), morally-questionable invading soldier (CoD, SpecOps: TL, Battlefield) or general bastard-type (most other shooters).

The game’s other strengths are many and numerous. The camaraderie between 50 and his numerous G Unit brethren is touching and sweet; they help each other open doors, climb walls and constantly offer each other advice; “grab that loot, 50”, and support; “you hit that sweet jump 50, how lovely was that”. The pace is also something that should be applauded, as BotS is a rollercoaster ride in the truest of senses. The entire game can be bested in about six hours, though that isn’t for a lack of content, just a testament to how quick and smooth the action within is presented. Rooms full of bad guys can be cleared quickly thanks to the fluid controls, powerful weaponry and beautifully implemented bullet-time-like feature, lending the game a euphoric, ballet of death and explosions quality, the like of which is rarely as satisfying as seen here. Finally, the decision to end the game with a car chase, arguably the weakest element of the entire experience, is strikingly original and sees developer Swordfish Studios embracing the left field like few studios before them.

50 Cent: BotS, then, is one of those rarest of games; a title that at first glance appears as shallow as the water covering one’s eyeball, though slowly morphs into a deep and often poignant experience. The messages it sends about morality, honesty and personal integrity are almost unique in a genre of video games that is usually content with solely wallowing in the glorification of violence. The brotherly love between 50 and his comrades could easily be translated into a feel-good summer blockbuster or gushing novel, its pitch is that perfect. And the action, oh the action, I think it plays better than Gears of War – any of them.

What strikes me the most is that I could easily have missed out on all of this had I been solely focusing on the cavalcade of new games released since 2009. Simply put; I’m glad I took a chance on this ageing title. That I enjoyed it so much fills me with anticipation at the long list of games I am yet to play before I retire my current consoles. Older things can sometimes be tiresome and awkward to enjoy, like cheese, waterbeds and stale cereal. Other times they can be as enjoyable, if not more so, as they day they were created, like cheese, relationships and fine, fine wine.

Everything ages and eventually slips into obscurity, though only if we let it happen. My grandma’s life has irrevocably changed with the passing of her husband, just as my dad’s moustache has irrevocably changed with the passing of time. They are both still fantastic things in their own right though, and both my grandma and father still treasure what they have. As things get older their value often increases dramatically, allowing us to not only reappraise them, but also place newer things within a more grounded context. Fifty years is a long time to be married. Twenty years is a long time to sport a moustache, regardless of its colour. As things age they become beautiful, valuable and sometimes, as with our memories of my grandad, and to a lesser extent 50 Cent BotS, timeless things to be treasured above all other trinkets.

Log in to comment