A Saga of Pixels and Pride

By pauljeremiah 1 Comments

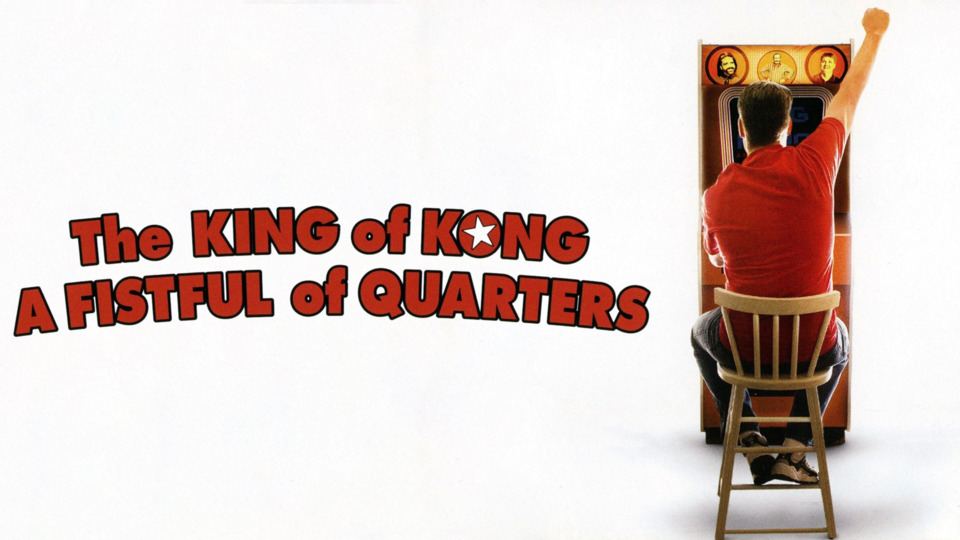

In the realm of video games, where digital conquests and high-score battles unfurl, few documentaries have plunged so compellingly into the heart of the joystick-clutching human spirit as The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters (2007). Director Seth Gordon, like a maestro conducting an orchestra of arcade cabinets, orchestrates a symphony of competition, camaraderie, and controversy that rivals the most enthralling narratives of epic quests.

The King of Kong revolves around the entangled lives of two determined men: the unassuming underdog Steve Wiebe and the reigning Donkey Kong champion Billy Mitchell. The stage is the arcade realm, the arena - a bygone era's nostalgic caverns of digital escapades. The narrative twine of Wiebe and Mitchell weaves through twists and turns as intricate as a classic game's labyrinthine pathways.

Enter Steve Wiebe, a man whose affable demeanour and quiet resolve belie a steely determination. The film introduces him to the throes of life's challenges - a lost job, a dwindling sense of purpose, and a drive to prove his worth. Enter Donkey Kong, the pixelated challenge of a generation. In Wiebe's eyes, the game symbolizes a shot at redemption and reclamation of his dignity.

Gordon captures Wiebe's journey with an empathetic lens, painting him as the quintessential everyman, an avatar of hope for us all. His journey becomes our journey, his fervent button presses echoing our own aspirations for achievement. The camera captures the tension of each attempt, the sweat-drenched palms, the furrowed brows, and the exultant smiles that punctuate triumphant moments.

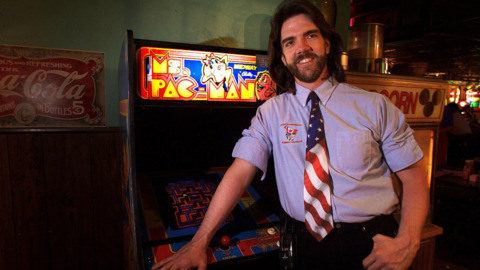

On the opposing side of the joystick stands Billy Mitchell, a figure shrouded in controversy and charisma. With a shock of dark hair and a sense of unwavering confidence, Mitchell embodies the essence of a self-made champion. However, there's more than meets the eye, and Gordon masterfully peels back layers to reveal a character as complex as any classic game's final boss.

Mitchell's charm and arrogance draw a thin line, one that invites the audience to ponder the thin boundary between greatness and hubris. It's an aspect that Gordon handles deftly, intertwining Mitchell's unwavering devotion to the arcade legacy with a tinge of scepticism about his methods and motivations.

The documentary excels in its ability to craft a tale that transcends the confines of its arcade cabinets. As Wiebe and Mitchell duel for the title of Donkey Kong champion, alliances are formed and rivalries fester. The enigmatic figure of Roy Shildt, a self-proclaimed villain of the gaming world, adds a layer of intrigue that rivals the most convoluted game plots. Shildt's inclusion serves as a testament to the rich tapestry of characters that populate this real-world saga, each more captivating than the last.

Gordon's narrative prowess is at its zenith as he guides us through the intricate chess match of high-score submissions, technicalities, and psychological warfare. The viewer becomes a part of this grand game, our emotions tethered to each pixel that scrolls across the screen. When Wiebe's efforts to dethrone Mitchell are met with bureaucratic resistance, it's an affront not just to him but to us all, a visceral reminder of the barriers that often obstruct the path to glory.

The King of Kong doesn't just chronicle a rivalry; it delves deep into themes that resonate beyond the realm of arcades. Ambition, camaraderie, sacrifice, and the eternal quest for validation are the warp and weft of this cinematic tapestry. Gordon stitches these themes into the very fabric of the film, ensuring that it resonates with both gamers and non-gamers alike.

At its core, the film speaks to the human need to excel and to be recognized for one's achievements. Whether it's Wiebe's relentless pursuit of a high score or Mitchell's desire to maintain his status as a legend, the drive to etch one's name into the annals of history is a universal trait. In this regard, The King of Kong is not just a film; it's a mirror reflecting our own desires for significance.

The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters is a remarkable cinematic achievement transcending its pixelated subject matter. Gordon's direction, coupled with the compelling characters and a narrative that unfurls with the precision of a well-played game, make this documentary a triumph in its own right. It's a testament to the power of storytelling to turn a seemingly niche topic into a universal parable of human ambition.

As the credits roll, one can't help but feel the weight of the journey undertaken by Wiebe and Mitchell. Through the digital haze of Donkey Kong's levels, through the maze of emotions and rivalries, emerges a tale that is as much about the pursuit of dreams as it is about the limits of human endurance.

The King of Kong: A Fistful of Quarters is a modern-day fable, a narrative gem that showcases the indomitable spirit of its characters while serving as an allegory for our own quests for greatness. In its pixelated heart, it encapsulates the essence of what it means to be human - to strive, to struggle, and to find meaning in the pursuit of the extraordinary ultimately. This film, like the games it portrays, will undoubtedly etch its name into the annals of cinematic lore.

Log in to comment