Interview: Clockwork Bird, Creator of Silicon Dreams

By gamer_152 0 Comments

Note: The following article contains minor spoilers for Silicon Dreams.

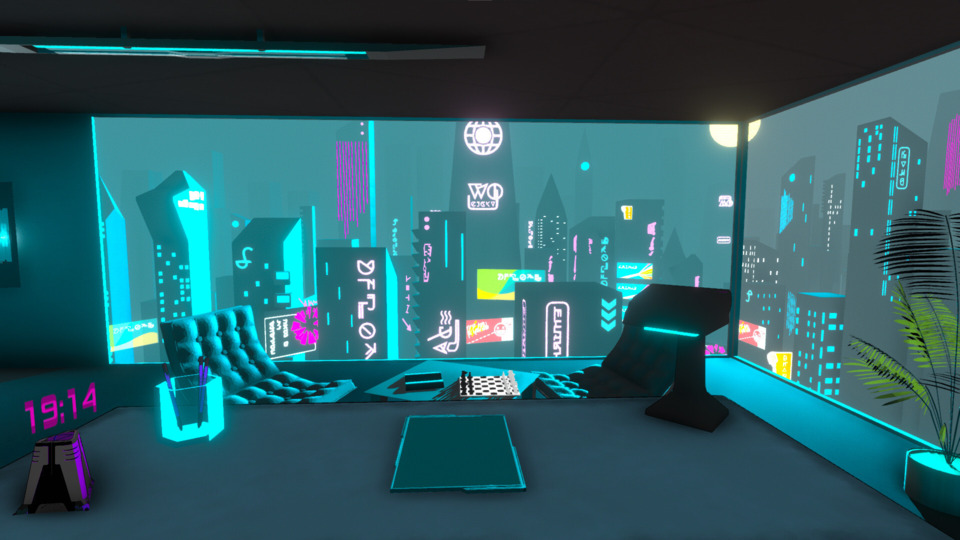

UK-born Jamie Patton and US expat Danny Adams are Austrian studio, Clockwork Bird. The developer's 2019 cyberpunk management sim, Spinnortality, challenges you to secure wealth and power on a global scale through unscrupulous strategies like propagandising and clandestine corporate dealing. In the same year, the studio released The Embers of the Stars, a nihilistic text adventure set at the universe's curtain call. Their most recent title is the 2021 narrative puzzler, Silicon Dreams, which blurs the line between oppressor and oppressed. In it, you carry out Blade Runner-like interrogations of humans and androids, all the while subject to the second-class status that comes with being an android yourself. Jamie and Danny put aside some time to talk to me about their creations.

Gamer_152: Your three games so far have been cut from very different cloth. Are there any essential concepts that make a Clockwork Bird game?

Jamie Patton: Curiosity about what a game can be. A desire to do something different, maybe something we haven't seen before. A commitment to the idea that games are art and that we should explore that space and see how it can affect players.

Danny Adams: In a very basic sense, it is our design philosophy to make games that haven't existed before, to explore this medium and to create settings, characters, stories and systems that are experimental and that stretch people's understanding of what a video game can be. Video games open such an enormous space for the types of stories that can be told and the methods by which those stories are communicated.

During my studies years ago, I was captured by the statement that "everything is political", even the choice to make a game that is non-political is a political choice. I want to make games that lean into that reality rather than away from it. We see a lot of problems in society that tend to be ignored or just accepted; "This is just the way things are". The intended effect of our games is to shine a light on these systems and assumptions without being preachy or communicating that there is one right way to think, and Silicon Dreams is a great example of this. On the surface, a relatively simple "visual novel" experience, I think we were really successful in making a game that allows (sometimes forces) players to make choices about their ethical and moral expression that range from difficult to impossible and being confronted with the outcome.

G_152: I understand James developed Spinnortality solo, and then the two of you began working together for Silicon Dreams. How did you meet and decide to team up?

JP: We met at a games conference in Vienna, where I live, and bonded over story games. We stayed in touch for the next few years, but just as friends. Yes, I developed Spinnortality in my spare time as a hobbyist, then ran a Kickstarter and applied for a grant to get the project over the finish line. It sold well enough that I was able to think about asking someone else to come join the team, and Danny was the one person I really wanted to work with. I think his ideas about storytelling in game design are brilliant.

DA: We met at a game conference in Vienna, where I was hosting a table of micro-TTRPGs. Our first interaction was when we were mighty witches drawing spells on our arms in marker. This game experience prompted a long discussion on the nature of games, digital and physical, and our views on the possibilities for what these games could do, and there was a lot of shared opinion. These discussions turned to more regular contact and conversation, which turned into developing a small side-project in Twine which resulted in the choice to team up and officially start making games together.

G_152: Spinnortality and Silicon Dreams are consciously political, and you've been open about many of the fictional influences on you, including Blade Runner and West World. Is there any political, sociological, or philosophical writing that shaped the worldview of these games?

JP: Both Spinnortality and Silicon Dreams are cyberpunk games, and we thought long and hard about what that means. In Spinnortality's case, I wanted to make a game that looked at a near-future world similar to ours and called it "cyberpunk", to talk about modern issues such as corporate overreach, gerrymandering, and the conflict of interest in political funding. This was influenced by cyberpunk works such as Neuromancer, Islands in the Net, Altered Carbon, and the Mirrorshades anthology, as well as Capitalism: A Ghost Story by Roy, which looks at modern capitalism under a critical lens.

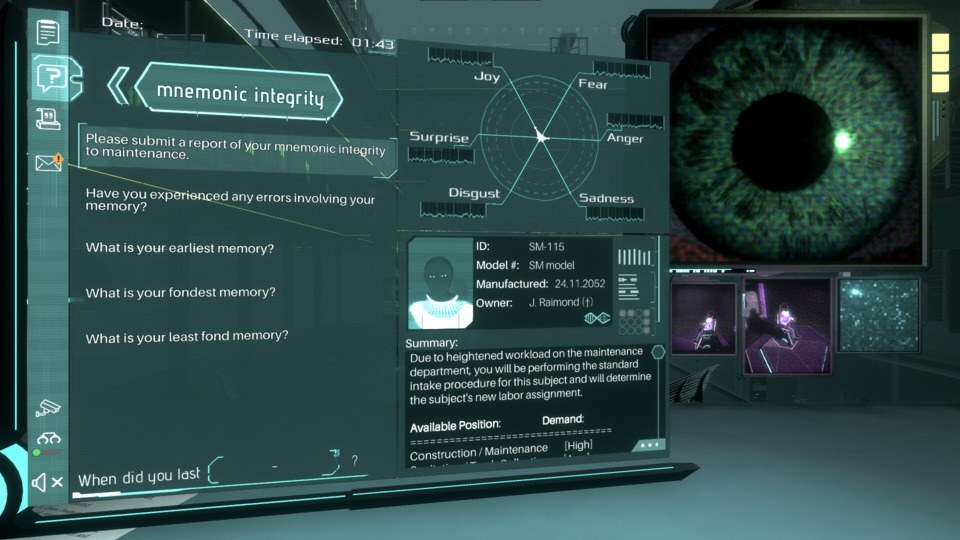

For Silicon Dreams, we wanted to zoom in. Where Spinnortality dealt with large-scale, wide-ranging issues, we wanted to see what life under cyberpunk capitalism looked like on a personal level. So everything in that game is focused on your relationship with the interviewee: the game is just a conversation with them. You see their body through the TV screen and their emotional responses on the readout. For this game, we were influenced quite a lot by Last Week Tonight, which dives into what it is like to live under current American capitalism day-to-day, and was a good inspiration. I also watched quite a lot of The Good Place, a philosophical show about being a good person, so I was quite interested in moral relativism (which could be translated as "do the best you can under the circumstances you have", which is very relevant for the moral choices of your put-upon protagonist).

DA: I can't reference any specific writings that influenced the worldview of these games. As Jamie mentioned, a lot of the inspiration from my side came from just reading the news and existing in this world watching runaway corporate power and greed propped up by politicians who are more concerned with protecting their donors' profits rather than their constituents. Particularly present in my mind during development was the prevalence of "us vs. them" tribalism and hope in a world that valued cooperation and raising everyone up together.

G_152: Kronos Robotics, the tech giant in Silicon Dreams, starts off fabricating prosthetics and collaborating with relief organisations but grows to become a slave factory and a massive driver of poverty. Were there real-world inspirations for Kronos's amoral transformation?

JP: The company we drew from the most was Apple, due to their success across multiple eras, their ability to corner several markets, and their modern ubiquity. It was also heavily inspired by questions we've been asking (and seeing asked on social media and TV) about the looming threat of automation. Kronos start out making something people need, or come to see as useful: prosthetics. This was inspired by Deus Ex: Human Revolution's attitude toward augmented humans: people wouldn't just start grafting stuff onto their bodies for no reason; there'd need to be a purpose for these augments to get started. But once they have a decent foundation as the market leader for prosthetics, they start buying up university projects to push their AI tech further and overcome the uncanny valley.

Soon they have good AI and decent prosthetic systems to let that AI do labour, and at that point, there's no reason they should employ human workers when they can easily automate everything with in-house tech. At this point, their trajectory begins to mirror Apple's: they notice an opportunity (an android/computer is released from a competitor and sells well), and they release their own version to corner that market. Soon they push the idea that these devices (androids or computers) are so useful there should be [...] in every home. Eventually, after attaining market dominance, they release model after model to corner the market with superior, expensive products and serve diehard fans (later generation androids/the iPhone). Some level of planned obsolescence is integrated into these products.

So, while Apple was a good skeleton to drape our "evil company" material over, I honestly think Kronos was mostly a patchwork of different companies. They're what happens when automation, ruthless market exploitation, and endless amounts of capital meet in one place. They weren't a nice company that saved people and then lost their way; they were always ruthless about making money. It's just that doing good in the world allowed them to turn a profit. It was never their main objective.

DA: Jamie mentioned Apple, which was a huge inspiration, but the largest inspiration for me was Amazon. The issues of market dominance and planned obsolescence are bad enough when one discusses a product, but I wanted to pay particular attention to the issues that arise when your product is a person or when your workers are not seen as people. While the lines may be more blurred in Silicon Dreams than in reality (Is an android a "person"?), it seems undeniable to me that under global capitalism, human beings are treated as nothing more than a commodity. A person's value is derived from the profit potential they can offer their employer to the point that it becomes acceptable to expect employees to urinate in a bottle so that they don't fall behind on their quotas. Much of my understanding of Kronos and fictional framing while imagining how they would deal with their workers was inspired by the stories of Amazon's treatment of their warehouse labour.

G_152: Silicon Dreams shows us androids from a lot of different walks of life and lets us explore each extensively. Did any of these characters undergo significant changes during development, and if so, how did that shake out?

JP: I'm not sure any went through huge changes: we had an idea of who they were, then fleshed it out. I think Atter, the doctor, became a bit more sympathetic during one rewrite: we wanted him to be a dick, but we wanted him to have reasons to be the way he was and human problems that were still relatable. We didn't want to excuse his actions, but we also wanted to acknowledge that everyone is a rich, complex world, even people we don't like. Two of the characters were written by an outside writer: the Hunter and, I think, the Vrogger? [Virtual reality blogger] Those went through some pretty big changes: we were happy to have the material he gave us, but it needed a fair bit of work to fit in with the other characters. So both were a little thin on the ground. You could have played through most of their scenes, but they were kind of sketches of characters rather than the full versions you see in the game.

JH-422, the nurse caretaker, also went through some rewrites. We wanted to create a character who was irredeemable, to show that not every android is a good person just because they are on the receiving end of violence. But that was quite hard to write, and kind of unpleasant to play, because you spend 30 minutes just talking to this horrible human being. So I think we softened him a bit.

DA: It would be fair to say that all of the characters went through significant changes over the course of development. We began development with a few very basic outlines of the types of characters we would like to include, but actual development and writing of each character was a hugely iterative process, and they all went through several rounds of tweaks, changes, or overhauls to their story, framing, and personality.

It may have taken more time to develop the characters in this way than it would have had we started development with a cast of fully fleshed-out and predetermined characters, but I think the game is better for the choice we made. For those who haven't played, Silicon Dreams can't be described as having branching dialogue; even this description implies too much linearity. This is a game in which the dialogue is written and designed in such a way that the possible paths a player can take are much broader than most games. Because of this, I think it was an essential part of the design to build them up iteratively to allow the dialogue to reflect their personality and to respond to the multiple ways a player may approach any discrete piece of information.

G_152: What's your professional relationship like? What did you learn about working together over the course of developing Silicon Dreams?

JP: When we got together in late 2019, we were both a bit wet behind the ears, I think. I'd launched one game and got lucky, and Danny had just come out of a game design course. We learned how to do production, track hours, figure out scope (we're still working on that, but it's a lot better), and this was also Danny's first game launch. We also learned the importance of visuals and presentation: for most of its life, the game looked terrible, and we literally changed the overall look about three months out from release when we won a prize, but the judges said, "Yeah, please use this money to hire an artist". We also learned that each of us has good ideas by themselves, but that something magical happens when we bounce ideas off each other. Silicon Dreams wouldn't be the game it is without that alchemy.

DA: Jamie said it all for this one. I can't add anything that he didn't already cover.

____

Thanks to Clockwork Bird and thank you for reading.