All-New Saturday Summaries 2017-09-16

By Mento 1 Comments

Welcome, all and sundry, to another episode of the Saturday Summaries. It definitely feels like September now, because there's far too much on my plate and far more on the way. Summer didn't quite make the dent I was hoping, and my personal wishlist for 2017 has exceeded 30 games as of writing. It's pretty sweet. But we're not going to go over backlog stuff again; it feels like that's the topic of every other Summaries.

Instead, I've been batting around a new game design theory, a unifying one that defines the approach a lot of video games appear to follow. The progression of any given video game falls into two distinct categories: The Loop and The Discovery. The Loop is what you're doing minute-to-minute, the meat and potatoes of the game. A game designer begins by defining what The Loop consists of and how long they can rationally make it last before a player's interest to wane. For that process to work, you also need The Discovery: these are the goalposts for players to follow, the promise of new mechanics, new characters, new story beats, and an eventual conclusion. However, The Discovery isn't always defined by a narrative thread: in the case of a fighter game, it can mean finding a new combo chain or working on fine-tuning the tech of a less-used member of the roster in order to determine their compatibility. A game that is all The Loop would be tedious, a game that is all The Discovery would be over too quickly. I'm making The Loop sound like a necessary evil - filler to artificially increase the game's length to something it can pitch as a selling point - but in an ideal scenario it's there to stabilize the pace of the game: if it moves too quick and has too much of The Discovery to impart in one swoop, the new additions won't connect with the player as readily. Like how a new mechanic will often be followed by a set of instances based around that mechanic in order to effectively tutorialize it, letting the player ease this new revelation into their current repertoire before introducing another. Both elements are essential, but The Loop is built to be endless while The Discovery is finite, since you can only put so much unique material into a game: the goal, then, is to ensure the game can balance the two for an ideal length of time and taps out as soon as it exhausts the latter.

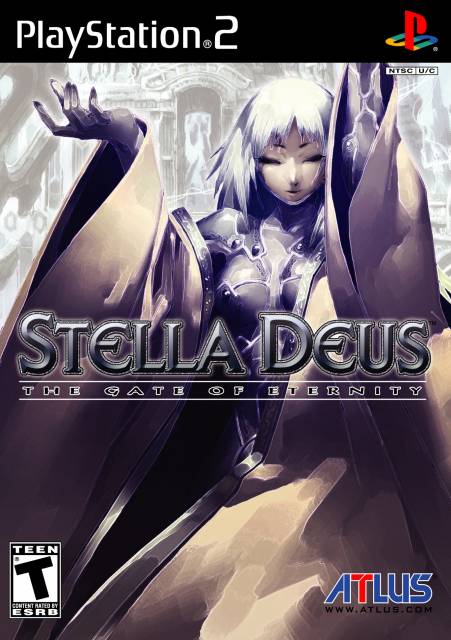

It's a fairly rudimentary and familiar conceit, but it's something I've been thinking about as I play a range of games this month both old and new. My September has been defined by Indie games that are built around emphasizing The Discovery aspect, their short runtimes filled to the brim with ideas, and the longer and occasionally workmanlike nature of PS2 games such as Stella Deus: The Gate of Eternity and Champions of Norrath, which despite having long stretches where the player isn't really learning anything new are still entertaining in their own right: in other words, games where The Loop is appealing enough that The Discovery is not required to be quite as prevalent. It's down to the designers to determine which balance is best suited for the particular game they're making.

I feel like there's all manner of follow-up contemplations regarding the ideal "length" of a game - I'm at a stage in my backlog now that I could do with fewer games that emphasize The Loop, but those I do indulge in are often worth the several dozen hours of semi-mindless fun regardless - and the virtue of the Indie market to quickly toss everything they have at you before bowing out in a welcome display of modesty and concision. Sometimes you just want a short and sweet puzzle game with a surfeit of creativity or a walking simulator that sticks around just long enough to tell its story, and other times you'd prefer to spend a lazy afternoon taking down a gigantic multi-floor dungeon in a solid RPG for the levels and gear you need to take on the next story boss. I'm content that my current gaming diet combines the two.

Speaking of what I've been playing, here's... what I've been playing. Next week: better segues.

- The Top Shelf is once again powering on all cylinders as we get closer to its conclusion, with another seven games quickly processed in hour-long playthroughs to determine their suitability for the titular shelf. This week included: the surprisingly approachable near-future military flight sim Dropship: United Peace Force; the pillar of the first-person stealth genre that is the original Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell; Rogue Trooper, the well-regarded adaptation of a non-Judge 2000AD comics character soon to see a remaster; Hyper Street Fighter II, a special anniversary arcade compilation of the most influential fighter game of all time; the supernatural stealth game Second Sight; the irreverent robotic third-person shooter Metal Arms: Glitch in the System; and the absurd sci-fi RTS/shooter Giants: Citizen Kabuto. Just two weeks and fourteen games left to go.

- The Indie Game of the Week this time was Waking Mars, a 2012 2D spacewhipper with a horticultural focus. There's something appealing about games that emphasize creation over destruction, where you're taking a barren location like the Lethe Caverns of Mars and filling it with a carefully curated ecosystem full of plants and creatures that are able to self-propagate to an extent after you leave. It is isn't strictly necessary to fill every region of Waking Mars with as much biomass as you can possibly produce, but the core of the game's Loop is figuring out how efficiently you can achieve this in every cave. Do you bring in seeds from other locations? Do you emphasize one plant type over another? There's a significant degree of freedom here, and I appreciate that as much as the game's constant updates to its plot and the scientific musings of its cast. It's the type of positive sci-fi that's focused on scientific discovery and less on unnecessary conflict. That doesn't mean Waking Mars lacks danger of any kind, just that there's no monsters to kill or villains to defeat. Your only enemy is getting stuck on a puzzle.

Stella Deus: The Gate of Eternity

Despite my best intentions, I didn't get any further into Danganronpa 2 this week. I've fortunately left the game at a point which will be easy to return to, as it has yet to take on the many layers of mystery and conflicting character motivations that its late game often evolves into. Instead, the first person got murdered, a second person got executed for it, everyone else is shocked and we're still in that period where the game is introducing itself for those who apparently arrived late. I will say that the first trial of Danganronpa 2 is a lot tougher than most of the early trials for 1, so they are anticipating that most of the audience is already familiar with how the game works, but I'm looking forward to the point where it stops repeating the beats of the first and becomes its own uniquely deranged thing. From the graciously spoiler-free reports I've heard from others, I shouldn't have too much longer to wait.

Instead, I've been trying to punch my way through a small but growing stack of PS2 games given brief assessments during Shelftember that I wanted to spend more time with before I consider their status in the final deliberations. I've set aside October as a sort of "catch-up" month for these games, where the usual Tuesday blogging slot for The Top Shelf will go into these second round survivors in more detail, but I thought I'd write a little more about Stella Deus and how it sets itself apart from its strongest influences like Final Fantasy Tactics and the early NIS SRPGs like Disgaea and La Pucelle.

Really, there's three aspects I want to discuss here in detail that I either skipped in the original blog post or downplayed too much, and it includes two features that I'm positive about and one where my feelings are a bit more ambivalent. We'll go with an ambivalency sandwich:

The Turn Order System, and the Clever Manipulation Thereof

Stella Deus borrows Final Fantasy Tactics's system for determining the turn order of every unit in the field. Rather than something like Fire Emblem where an entire side moves their characters in any order before relinquishing control to their opponent, each character in Stella Deus has a speed stat that determines the regeneration of "action points". When a character reaches 100 action points, it becomes their turn and they can spend those points either moving (the point consumption of each tile moved is determined by their stats and encumbrance) or using attacks and abilities. When their turn is over, they begin regenerating their stock of remaining action points back to 100.

Now, if you have a particularly fast character, what you can do is use up about 20-40 points just moving them a couple of spaces towards an enemy, and regenerate back to 100 before that enemy does. That way, you can get a full turn whupping on them instead of wasting half the turn getting close enough to pull off a single attack with the action points that remain. You can see in real-time the turn order restructuring after every action you perform, as the currently active character's portrait ends up whizzing to the end of the queue after using up all their action points, or sticking close to the front after only using up a handful. You can also skip someone's turn, either sacrificing a specific number of points to end up in a beneficial slot in the order - say, if two characters are surrounding the same enemy and you want the second one to get the bigger XP gain for finishing them off - or choosing which space in the queue to end up directly. Turn manipulation can lead to some amazing tactical gains, and I rarely see an action points system in a turn-based game granular enough to let you do all this. Rather than feeling cheap and cheesy, it adds a whole new dimension of strategy to the proceedings, as you cleverly place your turn after a distant opponent has kindly closed the gap between the two of you, or cast single quick healing spells to keep specific allies out of danger, ensuring that the healer will get to move again soon after in case someone else takes an unexpectedly strong hit.

The Catacombs, and the Stark Utility Thereof

Like many strategy games, Stella Deus balances its content between a linear series of critical maps that move towards big events in the story, and lesser optional fights intended to help the player grind or farm for the next big story encounter if they don't feel like they're sufficiently prepared for it. However, these optional battles are accessible from the main menu anywhere in the world via the Catacombs option: these are dungeon floors, 100 in total, that each have a set of opponents that match the floor's level. You have to defeat each floor to unlock the next, so no skipping around if you've been levelling up through the story, and these generic opponents are stacked with items and money to be earned which improve in quality and quantity the deeper you go. It is, effectively, the perfect training ground, though fighting through too many floors at once can leave you overpowered for the next story map.

The reason I'm ambivalent about it is because there's a lot of repetition involved. It only includes the basic enemy types - the game has around eight or nine classes, and the Catacomb opponents are any combination of these - and the layouts are very similar. What are often the only changes are the character placements - sometimes you're in a corner, sometimes you're smack dab in the middle - and the particular assortment of enemies you'll face. Axemen are slow and hit hard, thieves are the inverse, alchemists and archers can hit you from afar, healers are obviously nuisances that keep their allies in the fight, the spearmen can hit you across two tile distances as well as more pronounced height differences, and the swordsmen and brawlers while slower than the thieves can still sneak up on you in force if you underestimate them. A lot of the battles play out the same way, as you take aim at the more troublesome foes - alchemists, archers and healers - while ensuring that the melee goons don't surround anyone or get too close to your own vulnerable ranged units. It is when the game is at its most mindless, as you go through the same motions without any special consideration for the different map objectives or powerful boss enemies that you'll only see in the story maps. It does its job of getting you levelled and funded for what's to come, but it can feel a bit like drudgery.

It's worth noting that the enemies you face in battle on the final maps have level caps in the 40s, except apparently for the very final boss that levels itself to match your highest character, so around half of the Catacombs is entirely optional post-game fun for anyone who still has more gas in the tank.

Alchemy, and the Experimental Wantonness Thereof

The game feels a lot like Dragon Quest in how its alchemy works: you simply toss two items in the pot and see what results. Thankfully, Stella Deus always informs you of what a particular combination will create, and thus whether or not it's worth your time and the loss of the two ingredients. Every item in the game, from equipment to accessories to healing consumables to skill-teaching books, has an "item rank": this determines the quality of the item you can expect to receive when you combine two items together. A rank 5 item combined with a rank 1 item is likely to produce a rank 3, for example, so it's rarely conducive to keep old junk around to combine with the new hotness you pick up. However, even outmoded trash can be put to good use with the right amount of forethought and a sufficiently large pool of cash to draw from. If you're at an early part of the game where the only items available from the store are low-level ones, you can still buy, say, sixteen rank 1 items, turn them into eight rank 2 items, turn those into four rank 3 items, and eventually work your way up to a single rank 5 item: a weapon perhaps, or a piece of armor that is exceedingly more powerful than anything you can find at that point in the game. The downside is that stronger equipment is heavier, so you might need to unequip armor just to keep your movement speed somewhere reasonable.

There's also something to be said for the sheer degree of discovery involved. Sometimes you end up with weird combinations that result in an item you didn't think you needed until you saw its stats. Maybe you'll construct a skill book that provides an incredibly useful ability, like a passive that gives you a flat +20% boost to attack power or an immunity to a specific status effect that's been giving you trouble. Sometimes it results in an accessory that increases your "jump" stat, greatly expanding traversal possibilities as that character leaps up ledges they would normally have to walk around via a staircase or slope. There's also the convenient route too, where you simply pull up an FAQ of combinations people have found and work out the best route to the items you want. It's a basic and not particularly logical crafting system, but one that - like Shin Megami Tensei's demon fusing - can lead to a lot of pleasant surprises and what feels like early game-breaking epiphanies. You just have to be sure you can afford whatever you're working towards next, and recycle anything you can.