Mento + The Mechanics: Part 2

By Mento 5 Comments

Well, I promised a second part within the week and here it is. I've had some interesting replies already, so I wanted to start by thanking those who took the time to post and also for giving me some food for thought. Especially EVO, for allowing me to consider what does and does not qualify as a game mechanic, and CorruptedEvil, for informing me that many of the most mechanic-heavy games are those from the fighter and character action genres with optimized real-time combat systems that have been endlessly tweaked and updated by talented folk like Shinji Mikami and Hideki Kamiya. I'll be sticking to RPGs for the most part, since that's my wheelhouse, but every now and again I'll try to extend a little further afield into the sorts of games I don't play quite as often. There's certainly a lot of noteworthy but underappreciated mechanics in every genre.

Speaking of which, that's what we're looking at with this feature: Mechanics introduced in games that, for one reason or another, have yet to be fully embraced by the mainstream at large in spite of their merit. I'm highlighting these in the hope that it brings them some small amount of additional exposure, even if it's just to the dozen or so people who read these things. Though this will be the last part for now, I'll be sure to intermittently bring this series back whenever I have a new quintet of game features to, well, feature.

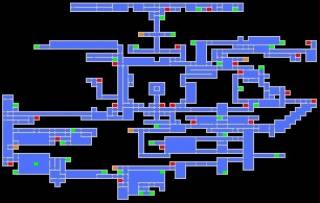

Case #006: Collectible Mapping Conveniences

Having a group of hidden collectibles in a game is far too divisive a topic and too ubiquitous a concept to ever be considered for this blog series, but because they're such a common sight these days (well, until you're searching for the very last one to complete the set anyway) there's a few other mechanics that have sprung up around them. An important one is how an open-world game filled with collectibles may provide the player with some means to track them down.

The most interesting aspect of this whole idea is not that the game feels it ought to deign to tell you where all its carefully hidden objects are, somewhat undermining the point of having a hidden collectible side-mission in the first place, but how every open-world game seems to approach the problem differently. With Bully, Saints Row 4 and Sleeping Dogs, the game only provides you with a map of the game's collectibles upon achieving a certain task - specifically with Bully it's completing all the Geography classes, with Saints Row 4 it's completing a task for Matt and with Sleeping Dogs it's finding and dating each of the NPC love interests. With The Amazing Spider-Man, the player must find a certain percentage of the collectibles on their own before the rest are revealed to them. Others give you an idea of where an item is but only on the player's mini-map, which means the player has to be somewhat close by before they can see them. Sometimes a game uses a distinctive sound to indicate if you're close, like the hidden orbs of Crackdown or the Golden Skulltulas of Ocarina of Time. SNES JRPG the Illusion of Gaia made its collectibles very hard to find, but also provided a location guide for all of them in its manual for the truly desperate.

In creating what many might consider a game mechanic that's simply a way to pad out the run-time of open-world games, designers inadvertently began creatively dealing with a problem that they themselves were responsible for. Instead of being quick to judge a game for having pointless collectibles, judge them instead for how they approach the dilemma of wanting to give players a break without giving too much away of what is meant to be an extended game of hide and seek. Make it too easy and hunting collectibles becomes more pointless than ever; make it too hard and players will abandon it as a snipe hunt. In a sense, it becomes like achievements: pointless busywork for some designers, yet another means to stretch the creative muscles for others. I approach both achievements and collectibles the same way as a result: I'll generally only persue them when the game designers have taken the time to work on them and made it worth my while.

Case #007: Treasure Recovery Runs

The temptation is to lean heavily on mechanics best known from the Demon's/Dark Souls series, because I don't think we'll be seeing the last of its brand of cautious, deliberate RPG gameplay after the laurels they've received. Though this feature is famous for many Souls players due to how indelibly linked it is with the game's progression, Treasure Recovery Runs -- or corpse runs as they're more commonly known -- pre-dates the Souls series and finds its roots in the earliest MMOs (and possibly even older games).

The idea that a game gives you some chance to recover what you lost is a fascinating compromise, as well as a great excuse for making the game harder than it needs to be. I brought up Post-Combat Rejuvenation last time as another example of how a game would introduce a feature that would appear to be a case of sparing the rod and spoiling the child, when really there's more rods than ever. Importantly, "afterlife" mechanics like these become paramount in lieu of a lives or continues system, which have thankfully all but been relegated to the hazy mists of time. I believe the Mario series persists with lives for much the same reason as my country persists with a monarchy: it's part of the history, but has so little importance that it might as well be an ornament. Shovel Knight, speaking of heraldry and rank, is a game that couldn't really keep using lives even if it is meant to be a deliberate throwback to the NES era. That instead players are penalized with the potential permanent loss of some of their cash reserves is a functional workaround.

But really, the genius of the corpse run is how it makes the journey back to the spot you died all that more momentous and tense. Considering that a second premature death will irrevocably destroy all those resources waiting around to be recovered, there's a lot more to lose even if you're retreading territory you've already conquered at least once. How sure can you be of that once-so-simple jump, or of that seemingly effortless skeleton warrior encounter? If you're going to be forced to repeat parts of the game over and over, it might as well have that added level of tension to shake things up.

Case #008: Challenge Level Indicators

Continuing with the MMO theme somewhat, a lot of open-world RPG areas tend to mix together overpowered monsters with those of a level more suitable for the player's party at that stage of the game. I feel the reasons for this are twofold: the first is to teach players the virtue of prudence, allowing them to size up an opponent and realizing they would be biting off far more than they could chew by approaching them. The second reason is to create a feeling of a verisimilitudinous ecology: a land where there's an apparent food chain and the strong prey on the weak absent the player's interference. If there's a fifteen foot T-Rex prowling around the same area as wolves and human-sized enemies, it's easy to imagine that it is there to predate on weaker creatures, while the weaker creatures do their best to avoid it. It is not necessarily there to be a boss monster for the player's party to fight; rather, it simply exists, ultimately irrelevant to the player's journey and should therefore be left alone.

However, in creating landscapes with their own ecologies like this, the player's party might find themselves encountering extremely tough enemies far too commonly, and because it's logical to expect that every adversary one encounters in an RPG can be defeated with the right tactics, it's a little too punishing if a group decides to take on a mighty-looking monster and gets instantly wiped out due to the vast difference in strength. What games like Final Fantasy XII and Xenoblade Chronicles have done is create a sort of color-coded system that indicates when a creature is simply too powerful to mess with. Rather than depend on numbers and levels, which don't always mean a whole lot to those trying to gauge an opponent's strength intuitively, a red warning bar over an enemy makes a very clear case that they are not to be trifled with. Since those two games have built much of their infrastructure around MMO mechanics absent the multiplayer aspect, it would be logical to assume such a system also exists in MMOs as well, creating areas filled with monsters of disparate power levels from which low-level newcomers and high-level veterans alike can find worthy foes.

I just love the notion that all these areas I'm visiting can operate on their own with their own rules even when I'm not around, and aren't just dioramas built to engage the player (though that is precisely what they are, by design). It indicates a level of thoughtfulness from the designers, a sense that their world is more than just a series of attractive (and, occasionally, hideous) vistas placed there for a player to look at. It's sometimes hard to justify spending more resources than is strictly necessary when working on level design, but when a designer chooses to create a region like Dark Souls' Ash Lake -- a region less than half of the game's players might ever see -- it demonstrates just how invested they are in building a world rather than propping up scenery around the player.

Case #009: Peripheral Town Crafting

I'm drawing directly from my all time favorite RPG Dark Cloud 2 (aka Dark Chronicle) with this one, but it's a common enough feature. The player is given custodianship of a fledgling village or town and can occasionally come back to provide funding and direction for the town's growth, sort of like a mini-SimCity smack dab in the middle of one's adventure. Some games let you have more control over this municipal growth than others, though there's often a benefit to increasing these player-sponsored towns to their maximum as it tends to unlock a lot of unique opportunities for the core game, such as powerful weapons and the like.

Besides Dark Chronicle's Georama system, which makes an entire secondary game out of its town-building, the most prominent example is probably the Suikoden series. In each Suikoden the player finds a base of operations and builds it back up from a ruin (or in the case of IV, an empty ship) to a mighty fortress. In part this is because every Suikoden has the player engaging in warfare, and it's not feasible to expect an entire army to be walking around just behind the player character every time they make camp or delves into a dungeon. The player also has a huge number of recruits to find, and not all of them are going to be warriors, so a base of operations affords vendors, decorators, spies, tacticians and other miscellaneous roles that can contribute to a war effort a place to hang out. Watching one's base grow in any Suikoden game (or Skies of Arcadia, for that matter) can be pretty special.

In other cases, like with Tales of Vesperia's Aurnion or Xenoblade Chronicles's Colony 6, the player is usually expected to stump up increasingly larger payments to increase the town's size, and with each new investment comes more utilities and services. You might also see cases like Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter's Fairy Village, which requires the player to choose how the town expands, and then extreme cases like Terraria where the player is solely responsible for the construction of a town of NPCs. When this element is done right, the player can enjoy an entirely separate, usually optional and far more calming type of gameplay to take a break from the monster bashing and dungeon diving for a while.

Case #010: Significant Enhancement Collectibles

I'm going to bookend this entry with two sets of mechanics governing collectibles, because I'm often in a bind to explain exactly why I occasionally bother to hunt the things down, and why I only seem to do so in certain games. Significant Enhancement Collectibles are those which give you a stronger reason for wanting to seek them out, beyond it simply being a thing you can do.

As far as I'm concerned, concept art isn't sufficient. What is perhaps more sufficient is songs from the game's soundtrack you can listen to (e.g. Saints Row 2, Shovel Knight), permanent stat boosts (e.g. Fallout 3, Crackdown, Sleeping Dogs, inFamous), a special bonus should all of a certain collectible be found (e.g. Bully) or additional backstory and worldbuilding details to peruse (e.g. Mass Effect's codex, anything with audio logs, the trophies of Super Smash Bros.). Though your mileage may vary on the value of any given reward for finding collectibles, cases like those above are at least more than simple TACOs: Totally Arbitrary Collectible Objects (you can thank Anachronox for that contribution to the gaming lexicon by buying the new Humble Bundle, which contains it along with Thief Gold and, uh... Daikatana).

It's the job of every game designer, I figure, to invest purpose into each collectible Easter egg hunt (which may or may not involve actual Easter eggs). To give a better reason for players to want to seek them out than simply "because they're there". Some players may well enjoy seeking them out for that purpose alone, but others will appreciate a slightly bigger carrot at the end of that stick. This is all, of course, assuming that collectibles are necessary in the first place. Since every open-world game seems to have them regardless, it's probably within one's professional pride to make them a worthy addition. If nothing else, you can always make a little puzzle or game out of recovering them, like the Riddler trophies of the Batman: Arkham series. In cases like those, figuring out how to reach the collectible can be its own reward.

The Bit At The End

All right, that's another five mechanics (or, if I'm being a little more honest, features that can encompass all sorts of mechanics) down. As before, feel free to post in the comments with your own answers to this question: What are some of your favorite less-utilized game mechanics, perhaps unique to a single game?

I'm going to try to get less general in the future, looking at some mechanics that maybe never left the singular game or franchise they originated in. I'll also endeavor to peek outside my comfort zone of RPGs and open-world games to seek some worthy candidates along the roads less traveled. Wouldn't hurt me to play more games of other genres anyway, especially if I intend to write about games as a whole. Wouldn't do to present only a small sample of the many flavors out there. As always, thanks for your views and comments and I'll be back with something different next week. I won't be shelving "Mento + The Mechanics" indefinitely though, trust me on that.

(Apologies to the guy who said he appreciated that I don't get too pretentious with these. Might've gotten a little too close to the line a few times. Good thing I dropped the whole "dichotomy between the player's desire to create and to destroy" business from the city-building stuff.)

| Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 |