The SNES Classic Mk. II: Episode XII: Guns N' Rodents

By Mento 1 Comments

The SNES Classic had a sterling assortment of games from Nintendo's 16-bit star console, but it's hardly all that system has to offer a modern audience. In each installment of this fortnightly feature, I judge two games for their suitability for a Classic successor based on four criteria, with the ultimate goal of assembling another collection of 25 SNES games that not only shine as brightly as those in the first SNES Classic, but have equally stood the test of time. The rules, list of games considered so far, and links to previous episodes can all be found at The SNES Classic Mk II Intro and Contents.

Episode XII: Guns N' Rodents

The Candidate: Lenar/ASCII's Gunple: Gunman's Proof

When curating a list of games to look at for this feature, I was consistently drawn to the most bizarre and unique. I feel that, if we're to preserve a selection of SNES/SFC games for this and future generations to enjoy in a micro-console format, it would be a mix of the established classics and the structural one-offs that, in their own way, would also go on to define the unbridled creativity of the period, even if they couldn't quite set the world aflame like their more famous contemporaries. After all, failure is every bit as compelling as success. Not that I'd call Gunple: Gunman's Proof a failure, per se, but the odds were stacked against it with their also-ran developer and a publisher that mostly released ports of dry computer games on the Super Famicom, many of which revolved around shogi or turn-based wargaming.

Gunple was instead one of the more imaginative games I'd come across for the first time when working on the SNES/SFC pages for the Giant Bomb wiki. It looked to all the world like a Western-themed version of The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past with a much stronger emphasis on gunplay, effectively making it more like The Binding of Isaac without the roguelike elements. It also incorporates a heavy dose of sci-fi and silly, vaudeville-like humor, which ultimately made the game feel equal parts A Link to the Past, Ape's EarthBound with its Americana, and Natsume's Pocky & Rocky. The resulting combination wasn't quite as riveting as I'd hoped for, but it still stands out as a novel idea.

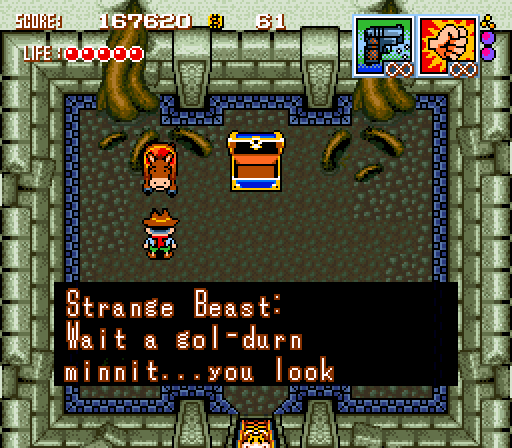

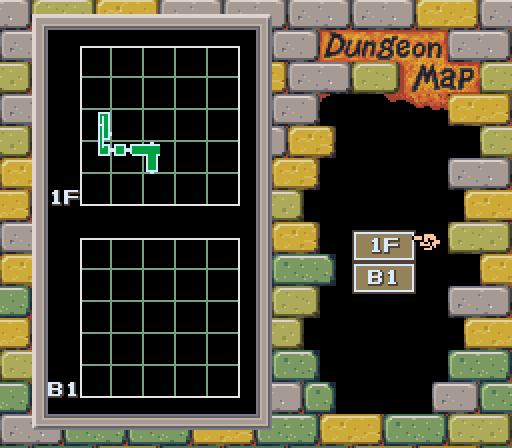

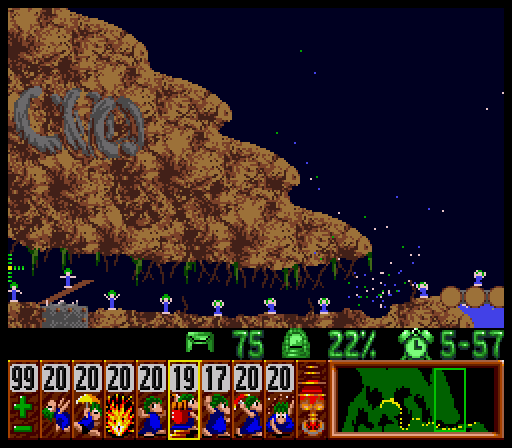

From A Link to the Past we have the general perspective, an angled bird's eye view with a very familiar looking system of drawing contours to represent higher ledges and cliffs, which the player can (but not always) leap off as a quick short-cut. The game also has seven dungeons, with a special eighth dungeon as the game's finale, and each can only be entered sequentially. Each has a map, and each has a boss at the end that drops a full heart container upon their defeat. It's a little flagrant, perhaps, but it really exists as a framework for a different type of game rather than a carbon copy. That makes it distinct from something like Neutopia or Crusader of Centy, which did their darndest to be a perfect Zelda ersatz that non-Nintendo owners could enjoy.

From Pocky & Rocky we have that same perspective but put through the rigours of a top-down shooter with multi-directional aiming. The player-named protagonist can fire in eight directions, usually more than his opponents can manage, and the player can hold down the trigger to fix his direction in place, allowing you to strafe around and shoot. The game's power-up system rarely gets more sophisticated than temporary guns you can collect - from SMGs and shotguns to progressively more outlandish and anachronistic weaponry like a flamethrower - and beyond health upgrades and a handful of permanent upgrades, there's not a whole lot to find. Dungeons have treasures, but they simply add to a "score" that can also be boosted by how much health you have after the boss fight, whether or not you still have a sub-weapon equipped, and how long it took you to complete it. It's a little surreal, as is the fact that you have extra lives and gain more for high score milestones (I never ran out, but I imagine it dumps you back in your home village and you have to walk back to the dungeon).

The story's standard Western stuff: a frontier town named Bronco Village has been beset by the minions of an alien criminal mastermind that crash landed on Earth several years prior. A space sheriff and his deputy arrives on Earth to apprehend the criminal, but because they can't survive long outside their spaceship in Earth's atmosphere, a young boy with a strong sense of justice consents to being his possession host while on Earth. The deputy Garo stays behind to fix the ship and give you hints about upcoming bosses, and you also meet another of their colleagues - the more reckless Mono - who is occupying a donkey named Robaton and appears occasionally to let you cross the overworld faster. Say what you will about how much it cribs from A Link to the Past, but it came up with the idea of letting the hero fast-travel with a steed almost two years before Ocarina of Time came about. The rest of the game moves along in a predictable pattern after that: you defeat a dungeon, collect a bounty back in town, get hints about a new dungeon, find some method of reaching it, and then completing that one and back to the start again.

There are certain elements of the game that feel a little underbaked. Money, for instance, comes in with every new bounty, but besides a few cheap key items and a boss that demands you pay him through the nose before he'll let you explore more of his dungeon, it has no other purpose. You can buy healing items from a shack south of town, but you can also regenerate your health to max just by taking a rest at your parents' home (this is also the only way you can save your game, and that's something that really should've been more obvious). The overworld's relatively small compared to A Link to the Past, and you can cross it quickly with Robaton, though it will upgrade the enemies after every few dungeons to keep it sufficiently deadly. The whole high score system in dungeons, and this split where you can either earn points from quickly finishing the dungeon or taking your time to explore grabbing treasures, just feels ill-considered also. You want to explore everywhere, because chests also have useful items like permanent upgrades, consumable bomb items which make bosses and tough enemy rooms easier, and full health items. You also can't complete a dungeon again after the boss is defeated, even if you walked all the way back to the boss room, so there's no way to "beat" your current score except by starting the game over. Besides granting the occasional extra life, which is something else you can also get from dungeon and overworld chests, the score does nothing.

Gunman's Proof had a really novel idea on its hands, but I'm not sure its developers could maximize on its potential. Instead, it feels like a flawed but entertaining oddity, the sort of game that inevitably falls into obscurity - a lack of a North American localization despite its North American setting certainly didn't help - but deserves another look.

But let's not get ahead of ourselves; we still have to put it through its P.O.G.S. paces, pardner:

- Preservation: Tricky to say. The aesthetic's not that strong, the Zelda trappings are evergreen and done better with lots of modern Indies, and there are certain flaws and oversights outlined above that drop Gunple from forgotten gem to just forgotten. All the same, the bizarre story that combines western and sci-fi tropes decades before Cowboys & Aliens is worth taking a look at. I'll invoke the usual idiosyncrasy rule that a game this singularly odd has aged well simply because nothing else has tried to iterate and improve on it in the meantime. 3.

- Originality: Gunple's more of a hodge-podge of ideas hastily sewn together to create a semi-coherent whole, but that honestly could be the acme of innovation as far as video games go. The big trendsetters for the past few years have been those which were built on familiar templates, but found an angle or tweak that resonated with a larger audience: Overwatch's new superhero direction for class-based online shooters, for instance, or Fortnite's crafting-heavy approach to battle royale. Gunple's not due for a massive comeback, but it stands alone as a Zelda/shoot 'em up hybrid with a western theme. 4.

- Gameplay: The difficulty curve crapped out around the end, but I found Gunple to be engaging in a gameplay sense. The multi-directional shooting and fixed direction makes it as appealing as a Smash TV, if not quite as entertainingly chaotic, and you can also pull off techniques like a close-range punch or crawling on the ground, which works to avoid enemy projectiles and traps. Speaking of the latter, each dungeon also has a scattering of Zelda style hazards, but nothing like the clever puzzles or the level design. It's overall pretty rudimentary, but does a fine enough job carrying the game and letting the humor be the star. 3.

- Style: The game's not generally a looker - the art direction comes from Isami Nakagawa, a mangaka that focuses on surrealist comedy - though there's something about the design of the NPCs and they way they jerkily animate which at least stands out. The protagonist's sprite spends most of the game with a slightly vacant look, not unlike Undertale's Frisk, but they can be expressive at certain moments of jubilation or panic. The enemies, though, include a great range of weirdos and monsters, almost all of which will pull off a taunting gesture if the player gets hit. Little touches like this elevate them from regular fodder to wiseacre jerks you love to gun down. I also really like the game's music in spots, like this overworld track for the south side of the world, or this spooky dungeon theme. 4.

Total: 14.

Other Images:

The Nominee: DMA Design/SunSoft's Lemmings

Excepting for a moment the fact that Lemmings would require a mouse peripheral to be played properly and that it's already available on a thousand other systems that would be better suited to host it, it's worth mentioning that Lemmings was one of the first big puzzle games and, really, phenomena in general that is intrinsically linked to the dawn of the 16-bit era. Originating on 16-bit systems, there's simply no way a weaker system would be able to handle a hundred tiny sprites doing their thing on the same screen simultaneously. It's one of those games that was born alongside the technology that permitted it, the sort of shortcut (but certainly not in the sense that it's easy) that births all sorts of trendsetters that simply couldn't have happened before, or at least not as successfully. Depending on who you talk to, it was either DMA Design's first huge breakthrough, or the best game they've ever made to this day even including their Rockstar North phase.

Lemmings is about as straightforward a premise as you could want for a puzzle game: you have anywhere from 1 to 100 suicidal rodents walking around the screen, happy to march off cliffs to their deaths unless a benevolent overlord - the player - figures out how to rescue as many as possible and escort them safely to the exit. The way to do this is to delegate tasks to individual lemmings: e.g. one to create a bridge while another blocks any approaching lemmings from the pitfall before the bridge lemming can cover it up. The difficulty is that you only have so many tasks to assign, and often more than a few obstacles and traps between your charges and their way out.

It's the type of game that acclimatizes you quickly to its rules - most of the early levels introduce you to the different tasks to assign, one by one - but becomes devilishly difficult quickly. A large part of that is that the game will have demanding timing as well as the analytical mind needed to suss out the level's solution. It's fine if you determine you need to activate a lemming at a certain point so that the one bridge you have will span an entire chasm, but quite another to hit it at the exact right moment to make it happen. It's why the mouse is unfortunately necessary; there's just no way to handle the timing with a cursor controlled by the D-pad.

SNES Lemmings is functionally identical to its console ports barring the mouse complication, with Japanese developer Sunsoft doing a fine job with the conversion and even adding a few extra-difficult bonus levels. For that reason, this P.O.G.S. rating is based on the quality of the game itself, rather than of any shortcomings of the SNES port in particular (which, to reiterate, are minimal):

- Preservation: They keep trying to remake this game, adding new tasks for the lemmings to perform or trying to make it 3D, and you honestly can't mess with perfection. It's also why the various Lemmings imitators like Humans don't quite work out. Lemmings is fortunate to be one of those rare "timeless" games that will probably remain as compelling as it is forever. 5.

- Originality: At the time, it was certainly original, and for the reasons I outlined above about the technology catching up to the conceit. It's a little less original now in light of what came later, but that shouldn't be held against it. Just to limit it to what the SNES saw in terms of people-corralling puzzle games, there's a few like The Lost Vikings and Gussun Oyoyo that might be comparable, but I'll always have a spot for those little green-haired goons. 4.

- Gameplay: Well, I think we have to face facts that it would be wildly impractical to release a second SNES Mini with a SNES Mouse attached, so this'll probably resort to D-pad controls. Simply put, it'd be nigh impossible to beat the game's hardest stages with the lack of speed and accuracy that standard controller buttons would get you. That said, there are few puzzle games that can match Lemmings, especially if you're a fan of those that require a balance of brains and speed. 4.

- Style: Hard to gauge. A lot of Lemmings visual and audio style is dated in some ways, and kinda neat in others. Each stage has a diorama type of quality due to all the tiny sprites wandering around it and changing it with their digging, stomping, pickaxing, and bridge-building, but visually the levels tend to involve a lot of basic looking terrain and the Lemming sprites are too small to leave much of an impression. I liked Sunsoft's treatment of the Lemmings music, which ranges from a few original tracks to a lot of classical public domain stuff that - even though I hear it in all sorts of places - has become indelibly linked to trying to figure out how to stop a bunch of little idiots from nuking themselves. I think I'll admit to a nostalgia bias and rate this accordingly. 3.

Total: 16.

Other Images: