Sacred Geometry: M.C. Escher and Manifold Garden

By gamer_152 0 Comments

Note: The following article contains major spoilers for Manifold Garden.

After the death of the Prophet Muhammad in 632 A.D., Islam's political and religious leadership fell to a succession of men called "caliphs". Each caliph ruled over lands and a community called a "Caliphate". Historically, there have been five major caliphates, each effectively comprising a Muslim empire.[1][2] In the west, we tend to think of the historical Muslim world as self-contained and mutually exclusive to Europe. Yet, at its height, the second caliphate stretched from Pakistan across the Middle East, through North Africa, and up the entirety of modern Portugal. It covered almost all of Spain and even a tiny bit of southern France.[1][3]

![Abstract patterning in the Alhambra.[4]](https://www.giantbomb.com/a/uploads/original/0/5370/3456559-alhambra_1.png)

The caliphates were a warm wind scattering Arabic art and architecture far from its point of origin. The most recognisable of this art to Europeans probably resides at the Alhambra, a magnificent palace in Granada, Spain, which dates back to at least the 9th century. One of the features for which the Alhambra is most prized is the intricate, tiling shapes painted on its walls and floor.[5] While, in Christian and secular spheres, we tend to associate abstract geometry with modern art, it has been prominent in the ancient world across many cultures and often accompanied or been the lens for religion.

Fractal patterns were implemented in Hindu temple architecture as Hindus believed that individual parts of the universe were similar to the whole, and they observed that natural formations like mountains and trees were also made of repeating, iterative patterns. A fractal is an infinite repeating structure: if you zoom in on one section of it, that zoomed-in region appears identical to the whole. Therefore, you can magnify a section of that section, and it will also look like the whole, and a section of that section of that section will look the same, and on forever. Fractals do exist in nature down to a certain depth in rivers, snowflakes, coastlines, lightning, and more.[6]

In a few eastern faiths, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, there are mandalas: circular and often symmetrical geometric patterns made to focus people spiritually. They can be pictures of the Buddhist cosmos, encouragement to seek truths about the universe, diagrams of the Buddha's journey, or another religiously significant image. Some are drawn with Gods in their centre.[7] Also in Buddhist philosophy, Indra, the King of all divine beings, lives in a palace which contains a net: a tiled geometric grid. At each point in Indra's net, there is a gem which reflects every other gem in the matrix and reflects the reflections in them, and those reflections contain the reflections in the reflections, and on infinitely.[8]

The abstract art of the Alhambra is similarly religious but has a somewhat different origin. The Quran forbids worshipping idols and gives God the title "maker of forms". The hadiths, a record of the sayings of Muhammad, tell painters to breathe life into their creations and threaten them with holy punishment. So, religious Islamic art has shied away from depicting living beings.[9] With artists being unable to replicate people or animals, they filled holy sites like the Alhambra with carefully practised calligraphy and abstract geometry.[5]

In 1922, a young Dutch artist, Maurits Cornelis Escher, visited the Alhambra. Escher had performed poorly in secondary education before enrolling in the Haarlem School of Architecture and Decorative Arts. The repeating shapes of the Alhambra awoke in him a lifelong interest in tesselation: the phenomenon of infinitely tiling shapes with no gaps between them.[10] We actually see tesselation a lot in block puzzle games and even the meshes of models in 3D games:

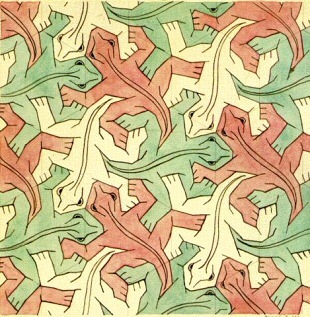

While we associate Escher with impossible environments, it's this preoccupation with infinitely cloning patterns, more than any perspective-bending, that enmeshes almost the entire body of his work. After Escher's moment of enlightenment in the Alhambra, he committed to mathematical studies, which would become the basis of his art. He called his return visit to the palace in 1936 "the richest source of inspiration I have ever tapped". He and his wife spent days making meticulous drawings of the Alhambra geometry, and Escher said he was "addicted" to tesselation.[11][12] Patterns very close to those in the palace reside in Escher's 1938 woodcut print Day and Night and his 1943 print Reptiles, while tesselation invades countless other Escher works: Cycle, Symmetry Drawing, and his series Circle Limit, Development, Metamorphosis, and Sky and Water.

This concept of a symmetrical pattern that repeats forever also appears in Escher's more famous art, like his 1953 lithograph, Relativity. In Relativity, each staircase and the world surrounding it is a mirror of every other, and the stairs are the same basic units looping forever. Bridging the gap between mathematics and art, Escher's pictures inspired geometers like Harold Coxeter and Roger Penrose. Coxeter and Escher started corresponding over a shared interest in the tesselation of spheres. Coxeter would include some of Escher's art in a presentation to the Royal Society of Canada in 1958. Escher then saw a tessellated sphere in Coexeter's publications and created his own version in the form of Circle Limit I (1958), a picture which appears not unlike a mandala.[13]

The British mathematician, philosopher, and physicist, Roger Penrose was impressed foremost by Escher's Relativity. Interested in dreaming up something similar, he worked with his father of the same profession, Lionel Penrose, to write the academic paper Impossible Objects: A Special Type of Visual Illusion. In the paper, the two discuss impossible objects: geometric constructions that can exist on paper but not in the real world. The text outlines two objects which follow the principles of the staircases in Escher's Relativity: there's the tribar, which was also discovered in 1934 by the Swedish artist Oscar Reutersvärd, and the infinitely rising/falling "Penrose steps".[14]

Escher read the Penroses' Impossible Objects and was inspired to create two more famous works: Ascending and Descending (1960), which shows monks climbing the Penrose steps, and Waterfall (1961), which depicts a waterfall that impossibly pours into the point from which it falls.[15] Again, infinities and symmetries are at the centre of Escher's work. All symmetries can be said to contain infinities. If you look at a pattern that is horizontally and vertically symmetrical, then you can take one quarter from any corner of it, rotate it 90 degrees, and you'll have the next corner. Rotate that 90 degrees, and you get the next corner. There's no limit to the number of times you can do this.

The ancient Islamic artists inspired Escher, who inspired the Penroses and Coxeter, who inspired Escher, and Escher inspired a whole genre of art, including a lot of video games. Q*Bert, Marble Madness, Fragments of Euclid, Echochrome, and The Bridge are just a few of the titles spun off from the style of the Dutch artist. Some games, like Monument Valley, even adopt the Andalusian architecture that a few of Escher's pictures lifted from the Alhambra. You could even make the case that all entertainment software that bends space or includes surreal geometric sections like Hyperbolica, American McGee's Alice, or Induction exist downstream of Escher's drawings. But William Chyr Studios' Manifold Garden might be the most M.C. Escher game there's been.

Adapting Escher's images into video game form comes with the challenge that the artist's most famous works are impossible objects; players may not be able to view them from all angles or interact with them in a manner that makes logical sense. For example, developers can't have the player ascend the Penrose steps in first person or have a physics engine with a consistent direction of gravity when liquid moves as it does in Waterfall. Video game worlds are not the physical world, and so, are not bound by all our physical rules, but they do have to be software engineered and are generally made to be playable. Therefore, they have to conform to the limits of our hardware, mathematics, and perception.

The trick to Escher's 3D illusions is that none of them is actually 3D; they are real 2D constructs that appear like fictional 3D objects. This is also the nature of 3D graphics on a computer screen. Even if data in the computer describes 3D objects and you think you see 3D objects as you play, they are all patterns on a flat plane because that's what your monitor is. This provides one method that a developer might use to fold Escheresque illusions and computer graphics together. Echochrome is a classic example. It lets you rotate its stages in three dimensions. However, when the stage is still, the 2D image of it can create the visual illusion of an impossible 3D object. Depending on the appearance of the level, the logic of how your character moves across it also changes.

Afterlife, a management game in which you play superintendent to heaven and hell, uses a figurative, narrative approach. One of the punishments for envy in the great beyond is the "Escher Pit", in which sinners exist on a surface where they endure some torture. They can see neighbours on an adjacent plane who appear to be in relatively better circumstances. Periodically, each soul rotates to the next surface, discovering, paradoxically, that the following punishment is always worse than the previous. By telling a story that has the spirit of Escher's Relativity rather than literally having us run through it, Afterlife doesn't have to worry about the contradictions in Escher's geometry.

Manifold Garden is also based on Escher and replicates its surrealism by letting us experience multiple different gravitational orientations in the same space.[16] We could compare Manifold Garden to Relativity or Escher's Another World (1947), which shows five planes, each with its own gravitational pull. Manifold's mechanics stay within the bounds of virtual possibility because they do not try to assert all those gravitational directions simultaneously, in the same place, as Relativity does. Instead, whenever we approach a wall, we can select it to make the world's gravity pull in its direction and only that direction. So, if I walk up to a wall and right-click it, that wall now becomes the floor, and my previous floor becomes the wall behind me. In isolation, the game's puzzles of placing cubes on pads and routing liquid to waterwheels aren't rewriting the book on brainteasers, but we can't get a complete understanding of mechanics by viewing them in isolation. Every time we use Manifold's hook mechanic of reorienting gravity, we change the nature of its space, and so, we change the nature of everything occupying that space, including the puzzle items.

Playing fast and loose with gravity like this could send us jetting off into oblivion at the drop of a hat. Imagine if you were walking down the street and gravity now pulled from in front of you instead of below you. But in Manifold Garden, there's always a net. The world tiles infinitely in all directions, so you can fall off of the bottom floor of a temple and land on its roof or step off of the east wall of a skyscraper and then land on the same east wall. I mentioned in my article on Superliminal that we're duty-bound to discuss all modern puzzle games in relation to Portal. Manifold Garden is a game in which the outer ceiling, floor, and walls of each instance are portals. You can stare at the bottom of the level and see the top, or look in front of you and see your back. Another way to think about Manifold Garden is as using the "screen wrap" concept, which was popular in early arcade and home titles such as Asteroids, but in 3D. It turns out that the depiction of impossible spaces goes back to the sunrise of video games.

It's through its sublime tesselation that Manifold Garden becomes not just an Escher game, but the Escherist game. It understands that filament that connects the artist's work and it develops his concept. If Escher drew scenes in which lizards, birds, and cubes tesselated, Manifold Garden is art in which the scene itself tesselates. As mentioned, the contents of a space are defined by the space itself, so to copy the scene infinitely is also to copy everything in it infinitely. The unique physics of Manifold Garden are also novel instruments with which to renew the Penroses' and Escher's more specific creations. Because water can drop off the bottom of a level and pour in from above, we can recreate the infinite waterfall in first person. Because Chyr suspends everything above and below itself, we get this neat remix of Penrose/Penrose/Escher's concept of simultaneously ascending and descending.

I don't want to give the impression that Escher and the Penroses were the only bright sparks drawing impossible objects. Earlier practitioners include William Hogarth with Satire on False Perspective (about 200 years before Escher) and Pieter Bruegel the Elder with Magpie on the Gallows (about 300 years). Oscar Reutersvärd, the Swedish artist I mentioned earlier, deserves a lot more credit for designing Escher-type illusions starting in the 1930s. Some of his structures pop up in Echochrome, and certain cross-shaped constructs in Manifold Garden resemble Reutersvärd's cubic space divisions.[16] Those cubic space divisions further share traits with Escher's Regular Division of the Plane, which was a particular inspiration for Manifold Garden.[16][17]

Many of Escher's pictures and the media they inspired, especially Manifold Garden, visualise or systemise the link between theoretical geometry and the reality we occupy. Escher's Day and Night shows two flocks of geese flying in opposite directions over square parcels of farmland, but in the centre of the picture, the birds and the ground below melt into tiled patterns. In his Metamorphosis I, we see a city on the left side of the frame and people on the right, but the intervening space is filled with abstract tokens that morph from the shapes of the houses to the shapes of the meeple. It's as though Escher is slowly whittling away layers of detail to show the geometric abstractions that underly our world. By demonstrating that objects and organisms can be physically described as cubes, squares, and triangles, he celebrates the powerful descriptiveness of mathematics and the geometry that ties all things together.

Manifold Garden also uses stripped-back versions of recognisable entities. Buildings are vast polygons with no patterning, trees are clusters of cubes, and birds are paper cranes. Colours in the scenes are simplified as, like Escher, Chyr makes liberal use of black and white, and where other colours do appear, objects usually only use a single shade of it. But the game also feels representational in the lack of context for our actions and the objects we encounter. Remember that representational art was also replete in the Alhambra.

In Manifold Garden, we can plant seeds, grow the garden, and banish "corruption". However, the graphics render all these ideas vaguely, and there is no written or spoken language to build them out. There is minimal recognisable wildlife, and seeds only sometimes mirror their real-world counterparts. They're basically blocks that reroute water, sit on switches, or grow into trees. I get the sense that the "birds", "corruption", and "seeds" are metaphorical rather than literal. The game is trying to explain to us a reality we would find too abstract by using analogies we are more familiar with. It's like how mathematicians will use the term "seed" to describe a string from which we can generate random values or talk about "squaring" a number when they want to talk about multiplying it by itself. Yet, those mathematical abstractions also feed back into our understanding of reality because we know there are maths that can describe the flow of a river or the branching of a tree.

I wouldn't be doing my due diligence if I didn't also discuss the connection Relativity and its brethren have to the physical concept of relativity. We're used to thinking of the universe in absolutes. We can say objects are objectively travelling at a certain speed, exist at certain coordinates, or are certain distances from each other. In physics, relativity was the rejection of this rigid view of position, dimensions, and velocity. Imagine I'm standing on a train that's moving away from a station, I'm bouncing a ball in my hand, and you are watching from the station platform. From my perspective, the ball is flying into the air and then coming right back down where it started; it is moving on only one axis. From your perspective, the ball is moving across two axes; with the momentum of the train applied to it, it is bouncing in an arc.

You might feel the impetus to say that your frame of reference or mine might be the "correct" one in this experiment, but how do you scientifcally prove the "right" perspective? You can't; it's all relative. It's a philosophical point as much as a scientific one.[18] Einstein's special and general theories of relativity (1912 and 1915, respectively) expanded that contextual conception of physical phenomena. His writings were evidence that even the length of objects or the speed at which time appears to pass depend on the observer's frame of reference. Likewise, many of Escher's pictures and Manifold Garden except the idea of absolute directions like a universal "down" or "left", or objects objectively existing in any one of those directions from any other object. Instead, it's all relative.

We could also read Escher's work and its children sociologically. Escher created his pictures in the period after WWII and on the cusp of the cultural upheaval of the 1960s. Ideas about the stability of European peace and the limits of atrocity capable on the continent had been blown apart. In the academic and pop culture spaces, concepts that had been taken for granted for centuries were under heavy scrutiny as new lifestyles, and new theories in various fields of study emerged. That never really stopped, and into that culture, Escher introduces these disorienting scenes in which reality is ripped apart and reformed. More than any other social development, pictures like Relativity or Ascending and Descending may reflect the increasingly popular concept of social equality. With the erasure of "up" and "down", none of the people on these stages exist above or below each other in a hierarchy; they are just all on their own paths. Depending on how they adapt Escher's work, various media cribbing from his style may replicate this commentary. Manifold Garden certainly does.

And then there's how Escher and co. describe the reality that does not exist. Mathematics persists abstract of the objects it describes, which means that we can do mathematics that only exists in the abstract and couldn't relate to real objects. In that sense, maths is transcendental. It can consider a pattern that tiles forever, a sudden shift of gravity without changes in mass, a waterfall that flows into itself. It exists in an imaginative space that is present in that ancient art, in Escher, and in games like Chyr's. Some less obvious references to transcendental mathematics in Manifold Garden include the higher-dimensional objects in the ending sequence, the mandala-like kaleidoscopes at the conclusion of each level, and the four-dimensional "God Cubes" that you must collect to enter the final area.

I'm not going to do that annoying new age thing where I claim that ancient worshippers had the same knowledge set as modern-day mathematicians or that STEM confirms the existence of the supernatural. That's woo. But the ancient Hindus, Muslims, and Buddhists, the mathematicians like Penrose and Coxeter, and artists like Escher and Chyr have all perceived the underlying code of reality surrounded by or represented through geometric patterns of infinities. In art, we often use "detailed" and "realistic" as a shorthand for "good", but by abstracting away from reality, mathematics and Escheresque creations find a broader descriptive and imaginative capability. In Manifold Garden, impossible buildings that resemble cathedrals and temples articulate that geometry describes celestial forces. Thanks for reading.

Notes

- Kadi, W., Shahin, A.A. (2013). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press (p. 81).

- Caliphate by Asma Afsaruddin (July 20, 1998), Britannica.

- Age of the Caliphs by Federal Depository Library (Date Unknown), Mapping Globalization Project.

- Adapted from a photograph by Dmharvey. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported.

- Tilework in the Alhambra by Dosde Staff (Date Unknown), Dosde.

- Dhrubajyoti, S., Kulkarni, S.Y. (2015). Role of Fractal Geometry in Indian Hindu Temple Architecture. International Journal of Engineering Research & Technology.

- Mandala by Joshua J. Mark (October 13, 2020), World History Encyclopedia.

- Loy, D. (1993). Indra's Postmodern Net. Philosophy East and West vol. 43, no. 3 (p. 481).

- Figural Representation in Islamic Art by Department of Islamic Art (October 2001), The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Wall mosaic in the Alhambra by Erik Kersten (October 20, 2018), Escher in het Paleis.

- The Regular Division of The Plane at the 'De Roos' foundation by Erik Kersten (September 12, 2020), Escher in het Paleis.

- Maurits Cornelius Escher by J.J. O'Connor and E.F. Robertson (May, 2000), MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive.

- Escher and Coxeter - a Mathematical Conversation by Sarah Hart (June 15, 2017), Gresham College.

- Penrose, L.S., Penrose, R. (1958). Impossible Objects: A Special Type of Visual Illusion. British Journal of Psychology vol. 49 (p. 31-33).

- The OMG moment of Waterfall by Erik Kersten (October 12, 2019), Escher in het Paleis.

- Level Design in Impossible Geometry by William Chyr (September 19, 2016), YouTube.

- Oscar Reutersvärd by Erik Kersten (February 6, 2021), Escher in het Paleis.

- What is relativity all about? by Don Lincoln (January 24, 2018), YouTube.

- Low resolution and cropped versions of Escher's artworks are used for critical and educational purposes under Fair Use.

All other sources linked at relevant points in the article.