Welcome, all, to the penultimate Sunday Summaries of 2016, and possibly ever. I've got ideas for long-form blogging features next year; in particular, I hope to try a few familiar formats to buoy the week with content that's easy to plan out, much like this feature, and pepper in a few less conventional ideas in the gaps.

But before we get into that, we should broach the topic of GOTY. I will be creating a list and awards blog some time in the following week, since I can't continue putting it off much longer. I particularly want to get in before the official GOTY content starts showing up, at least. I've pared down the usual award categories a little - I haven't played a single 2016 Nintendo game, so that's one of my recurring awards out - but I've got enough to move forward with. I'm going to do the weird thing of creating both the "static" GOTY 2016 (which won't be changed after December) and the "adjusted" GOTY 2016 (which will be rearranged at the end of each subsequent year to include new entries) at the same time too.

My family and I celebrated Xmas already - some of us work in retail, and can't exactly take next weekend off - so I've got a few late entries for my GOTY list to try out. There's this dilemma right now of either rushing through those games this week to fit them into my various GOTY materials, or to actually take my time with them to fully appreciate their quality. I think the sensible course of action is to figure out how long an average playthrough takes via HowLongToBeat.com and then order them by shortest to longest. I'm excited to play all four of them at any rate, and hopefully have more to report later this week.

New Games!

There's only one new release that I'm interested in over the next seven days and it's WayForward's Kickstarted Shantae sequel, Shantae: Half-Genie Hero. Given the extra budget, it makes me wonder what this one will look like compared to its slightly more modest predecessors. I love the Shantae series, but there's no denying that they tend to be a bit samey, not unlike the IGAvanias they evidently venerate. Even if WayForward used that extra cash to turn out a luxuriously-styled 2D platformer, like a Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze or Rayman Legends, I think I'd be entirely OK with that.

There's other games too, of course. I guess that Wild Guns Reloaded got pushed back to this week? That's a little awkward, since I already wrote about it last time. We also have the new Telltale Walking Dead season, if anyone still cares about those, and there's like twenty new games on Steam because there's always a whole bunch of new Steam games. That sluice gate broke a long time ago. Also, there's some hacking game for Wii U called Radiantflux: Hyperfractal, which... I didn't even know there were new Wii U games coming out still, let alone ones about hacking with rad names.

Wiki!

I was concerned that I'd get nowhere with this list of games that'll feature in Awesome Games Done Quick 2017 - due to start on the 7th of January, letting what might be an even shittier year at least begin with an ounce of promise - but it's actually moving at a clip. I've completed three of the seven days of scheduled speedruns, with a significant chunk taken out of the fourth. What's more, a lot of the longer speedruns tend to show up towards the end, so I'm probably well past the halfway point. The final two weeks of wiki editing work this year should see the project through to its end. Especially with all those extra Giant Bomb podcasts to listen to.

However, I've noticed I'm letting myself get a little sidetracked by this AGDQ's disproportionately large selection of NES games. I've just ended a mid-sized NES wiki project which involved adding a large number of Virtual Console releases, and many of the preferred speedrun games are also popular enough to have been made available on Virtual Console as well. Hard to avoid the habit of adding all those VC releases as I come across them. It's also getting depressingly real just how often Nintendo has tried to sell us the same game over and over: if I were to pick a major game, like The Legend of Zelda or Castlevania, that saw an FDS (Famicom Disk System) debut and included all three modern Nintendo systems that each support their own distinct variant of the Virtual Console service, that's five platforms that Nintendo has sold that game on. In fact, if we just look at Metroid, it's been released a total of seven times: FDS in Japan, NES in NA/EU, as part of the inexplicably full-priced "Classic NES Series" GBA range, on the Wii Virtual Console, on the 3DS Virtual Console, on the Wii U Virtual Console and most recently via the NES Classic Mini's built-in selection. And folk were worried that Nintendo would somehow lose their "purity" if they started selling Android games? Point is, I keep wanting to stop and add all those extra releases so I won't have to do it later, but if I did that then I'd never get this project done in time.

Anyhoo, 2017 will belong to the SNES, like most years. The European SNES will celebrate its 25th anniversary next April, to join the North American SNES's 25th this August and the Super Famicom's back in November 2015. While it's not really a huge deal outside of Europe itself, I'm hoping this one last "25th Anniversary" date will give Nintendo an excuse to put out the SNES Classic Mini, or maybe even the first "SNES Remix". My goal in 2017, then, will be the completion of any outstanding SNES projects. Not just 1996's full release schedule, which is up next, but all the remaining years of the console's lifespan and every one of its miscellaneous releases, including all the SNES Virtual Console releases (that's been a thing of late) and those of the Japan-only Nintendo Power disk writer service, which is not to be confused with the American magazine. The notoriously poorly-archived Satellaview line-up too, I'm hoping.

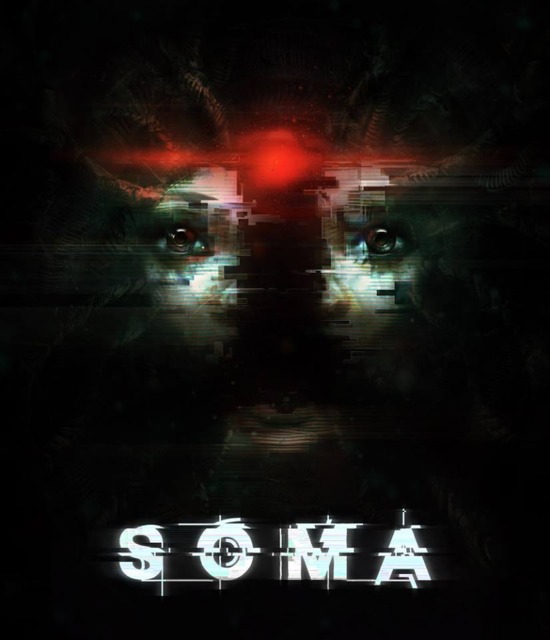

SOMA

After the disappointing Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs, I sorely wanted to check out Frictional Games's SOMA to see if the problem lied in that developer's increasingly hoary "hide from monsters" survival horror approach, or if Machine for Pigs' developer TheChineseRoom simply misjudged how Frictional is able to make such suspenseful horror games. Frictional did, of course, create the original Amnesia: The Dark Descent, a game I "enjoyed" to the extent that anyone might enjoy a horror game. It's such an odd genre, in that the more effective it is at its intended goal the harder and less fun it is to play, but then you don't necessarily play those games for a psychological sensation as straightforward as "fun". Like horror movies and other horror fiction, the goal is to invoke an uncommonly pursued emotional state in its consumer - fear - and the quality of the product is determined by how effectively it manages to convey those scares and spooks. If you create a terrifying game with a deliberately-paced mystery at its core that slowly reveals more of the game's plot and the player character's role in it, and a player quits early out of pure fright before learning anything, have you succeeded or failed in your objective? Which one takes precedence: the horror or the story that generates it?

Mechanically, SOMA greatly resembles Frictional's other games. It's probably far more like their Penumbra series than Amnesia, since there's almost zero emphasis on creating and chasing light sources with a finite means of creating them. They're still banging that "don't look at the monsters" drum too. For each of their games, they've implemented a frankly contrived reason for never looking at the game's antagonistic creatures: in Penumbra, it was to avoid panic attacks; in Amnesia, it followed a very Lovecraftian approach where's one sanity naturally starts to crumble when forced to countenance creatures that simply should not be; in SOMA, it's more that there's something about the nature of the monsters and the player character's relation to them that causes the player's vision to glitch out and blur. I'll have to get into more plot details to expound on that further, but while it makes more sense than the previous two cases, it still feels a bit... convenient? I guess? Like the idea that looking at the monster would somehow have a deleterious effect on the protagonist is one that works in an abstract gameplay-sense, because it then makes the creatures in question far more terrifying if you aren't allowed to look at them, but at the same time it's hard to implement that as a game mechanic when there's no sufficiently sound explanation why you can't check out the monsters skulking around, especially since it's important to know where they are so you can avoid them. Frictional keeps trying to make that idea work with different rationalizations for why you can't "stare into the abyss", though, so bless them for that.

SOMA switches narrative genres from the 19th century to sci-fi, which is both a necessary and welcome switch because there was no way to directly follow up Amnesia: The Dark Descent (as TheChineseRoom discovered). SOMA's narrative structure is an unusual one in terms of twists: there's a few huge ones right near the beginning which are used to contextualize SOMA's core "mission", and the rest of the game's plot has a fairly conventional progression in pursuing that mission to a semi-predictable outcome. Like Inside, the game's flow is a major part of its appeal and so is the way the game explores major themes of identity and consciousness that are tied directly to those aforementioned twists, and I can't really be as skittish as I usually am about spoilers if I intend to get as deep into it as I would like. Keep in mind that it will be spoiler city from here on out - you may have gleaned the major ones already from promotional materials or the Quick Look, since they arrive early, but that's your warning.

The player is a regular Torontonian store-owner from 2015 named Simon who, after suffering brain damage in a traffic collision, goes to receive an experimental brain scan from a new medical device with the intent of helping his doctors determine how he can be cured. Instead, Simon suddenly awakes in the future on a derelict research station. You learn a number of shocking revelations in quick succession: it's a hundred years into the future, something happened to wipe out 99% of the Earth's population, the station is at the bottom of the ocean and part of a larger facility of Greek-lettered stations named PATHOS-II, the entire facility's been taken over by a virus-like AI infestation that manifests as a lot of gungy black pipes and orifices, if there's any people around they're in robot bodies, and that Simon himself is one of those robots. By following a friendly voice to a different research station, walking along the bottom of the ocean to close the distance, the player encounters Catherine. She's another fellow human mind trapped in a machine who knows what's going on and asks Simon to help her complete her life's work of The Ark: a computer server that contains the brain scans of humanity's last few survivors in a virtual utopian environment which will preserve whatever remnants of mankind remain, and needs to be launched into space to ensure its solar collectors can continue to power the device for thousands of years. At the bottom of the ocean, where it is currently, the power consumption won't last nearly as long, and it threatens to be swallowed up by the rogue AI "WAU" that is taking over the base like a malignant cancer. The game then has the player move from one station to the next, often because of unforeseen mishaps, until they can find the Ark and then move it to an underwater high-tech electromagnetic cannon to be launched into space with Simon and Catherine's consciousnesses on board.

After that series of initial reveals, the game simply has the player pursue the Ark and figure out how to launch it. While you're trying to complete those few specific long-term goals, each new wrinkle introduces a detour or an additional task to resolve before you can move on. These naturally put you in harm's way of the WAU: a machine intelligence that is wholly distinct from a human being's thought processes. Rather than treated as a human-like intelligence that has gone insane, say a HAL or a SHODAN or a Skynet, this AI is instead more like a virus or some other simple organism that perhaps best exemplifies where artificial intelligence is at presently. Its core programming is intent on saving humanity, but it doesn't have the same lofty ideals about individualism and freedom that a human might, and so the way it is preserving humans is by turning them into biomechanical creatures that - while no longer sapient - are at least built to last. Other humans are placed in a nightmarish form of stasis that keeps them alive and aware even while their bodies wither away to nothing. It's an impressive twist for the game; before you come to understand what the WAU is or how it thinks, it resembles some kind of alien infestation, like the oily black Giger biomechanical goop that the xenomorphs call home. The actual explanation turns out to be even scarier, because an inscrutable machine has determined the future course of humanity and there's no-one really left to stop it. That human civilization was wiped out by a comet, which made the planet's surface unsurvivable, or that Simon was brought back because his mind scan was built into later models of the same machine as one of the "defaults", is a little less impactful. I do like that, as the guinea pig for this new technology, Simon's consciousness has been used for the sake of advancing medical science for who knows how many different attempts to recreate a human mind from a computer reading: there's little explanation given for why Simon woke up this time in the modified body of a human corpse in a diving suit, just that this happens to be the Simon consciousness that the player assumes.

This is the major metaphysical quandary that the game presents: Simon's consciousness isn't so much a unique occurrence than one that has been copied endlessly. At one momentous juncture in the game, Simon needs to transfer his consciousness to a hardier "power suit" in order to travel to the abyssal parts of the PATHOS-II facility; those stations situated so far beneath the surface that the pressure would crush his original suit like a soda can. Catherine begins the process, then nonchalantly lets it slip that Simon didn't so much transfer his consciousness but copy it, leaving his original consciousness in the old suit. Simon's understandably livid about this, leading to the first of many heated verbal spats with the more pragmatic scientist, and the player is given the option - with no explicit repercussions - of either letting his original "body" eventually wake up later on his own with no hope of making it to the Ark, or shutting it down while it sleeps and effectively killing that Simon. The player, meanwhile, has jumped from Simon's original consciousness to this new one, and the in-game Simon sees this as a "coin-flip": a specious attempt to explain why the player has switched over, even if the truth is that there are now two concurrent Simons. The player also finds out what happened to the original Simon of the 21st century, as if to further reiterate that the player character is merely a copy, or a copy of a copy, or a copy of a copy of a copy.

One of my favorite elements, and one that I wished the game could've expanded on via a menu page or codex even though it wouldn't have added much, is following the often context-only subplots of the station's other employees to their eventual fates. You're driven to figure out what happened to Catherine at least - the Catherine consciousness that's with you was one of the first to be scanned and uploaded, so while she's knowledgeable about PATHOS-II and its employees she learns along with you what eventually happened to the Ark, her team and her own physical self - but there's also a large number of secondary characters that you learn about from personal keepsakes and log entries and you find yourself invested in figuring out what happened to them too. The player has the ability to "datamine" computer recordings of voices and dialogue, drawing from intercoms and the "black boxes" inside the heads of employees, which were used to track their whereabouts and current medical status. When you reach a station full of headless corpses, you get nothing but static from your datamines and have to rely on more conventional information-gathering methods to figure out what happened: it turns out one employee learned what the WAU was trying to do and endeavored to help another scientist shut down its core, and before she could move out the WAU "shrieked" - the result being the simultaneous destruction of everyone's black box implants, which in turn 'sploded their heads as well. It's grisly, but it's one of the game's fun many little mysteries that you can figure out with some probing. While I was always focused on whatever my current objective was - the game does a fine job of ensuring you always know what to do or where to go, usually via Catherine and her instructions - I was always more interested in what happened to each of the stations, and what resulted to the various named characters that I've been listening to and reading about. One example is a gregarious dispatch operator named Strasky who was introduced early on - he's heard speaking to the two mechanics you meet at the initial Upsilon station - and half the game goes by before you finally find him.

There's much the game doesn't tell you, also, and I think a lot of that is deliberately kept unclear. Almost all of it concerns how the WAU operates, and how its horrific "post-humans" mutants created to preserve humanity work. It's not clear if these post-human mutants are completely mindless, or their original minds have turned irrevocably insane by the WAU's genetic tampering, or if they're animated corpses controlled by the WAU directly and used to ensure that it can resume the imperative it was programmed to complete. Or maybe any of the above on a case-by-case basis. That inscrutability is a major element of the game's sense of horror, and is also the slightly spurious explanation given for why the player can't stare at the monsters too long: the WAU has infected the player's suit as well, to some minor extent, and by looking at the monsters, the WAU is able to exert greater control over the player and cause them to glitch out. It also means the monsters know where you are if you look at them for too long, because the WAU is relaying that information back to them in some hivemind-like sense. Something about the WAU creatures' limited conventional sensory functions means that you can often effectively "hide" in the same room as the monster in plain sight, just as long as you don't look at them or make too much noise. Each monster is slightly different though, based on the mutation, so there's never a guarantee that it doesn't know where you are. I used to run into rooms and shut the doors behind me, but that stopped working when the monsters figured out how to open them (or the WAU just did it for them remotely). Cleverly, the game sets up in the prologue that Simon starts getting headaches and vision deterioration whenever he's stressed due to his brain damage, but given that ceases to be a factor as soon as he's given a robot mind/body it's probably more of an elaborate red herring. Or maybe it's psychosomatic? The title of the game is in that word somewhere, so I guess I can't discount it.

I really liked SOMA. I might mirror the sentiment others had, including horror-aficionado Patrick Klepek, that the game didn't really need its monster encounters. Occasionally a game will feel compelled to include more elaborate gameplay for the sake of it, as was also the case with Murdered: Soul Suspect's wraith encounters or Deadly Premonition's "otherworld" dungeons, but I didn't feel that it was too distracting here. Without those sequences, you run into the danger of making the facility feel too safe when it's very emphatically made out to be anything but. The peril has to be real, and Frictional likes its little games of hide and seek too much to quit them. At the same time, they're definitely not the highlight of the game, and I can understand the frustration of having one's exploration of this amazing setting and the little investigations of what went on in any given station, reading through computer logs and datamining the nearby intercoms, interrupted by these sequences that comparatively add very little to the game's overarching narrative. There were also times where the game went for a more action movie pacing, where you were required to run away as parts of the level were imploding or a monster was chasing you, and they felt a little incongruous to the leisurely-paced and suspenseful atmosphere that 90% of the game operated under.

It's very well-written and I liked that it played around with questions about transhumanism and the nature of consciousness in a format that can make those thoughtful philosophical predicaments feel more immediate and pressing to the viewer, using the game's first-person perspective and how the player's never quite sure which "Simon" they currently are. Or even if it matters much. Definitely a thinker, this one.

Let It Die

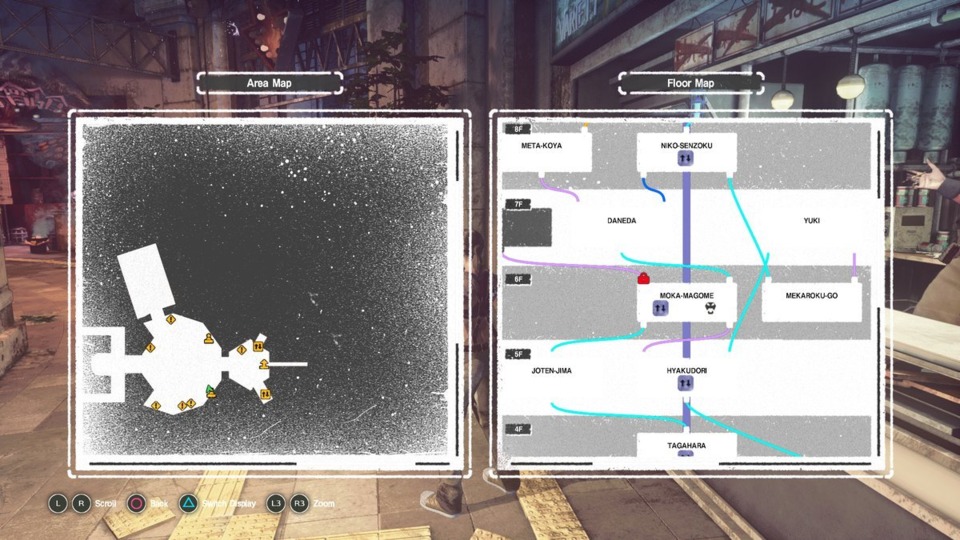

I'm not sure what it is about Grasshopper's Let It Die, but I decided to resume from where I left off after the Go! Go! GOTY! series earlier this month and have played several more hours of it since then. I had died and lost my current Fighter after exploring three floors without finding a single elevator and felt a little ticked off by it, but it's gleaning on me now how this game works. The tower is built with multiple floors, the goal being to defeat the boss at each tenth floor until you reach the top at floor 40 (and I want to believe the game has plans to add extra sets of ten at regular intervals). However, there are also multiple "stations" per floor: many of these "stations" - what I call them because they all have subway-style Japanese names - have multiple branching exits leading off to different wings of the tower. The central column contains the main elevator: this is the one that takes you back to the "waiting room" hub area, as well as to all the mid-bosses I've fought so far, and is situated in the middle of the tower as it appears on the world map. However, this central column abruptly stops around the 4th floor. The key is to explore these side stations for an exit that leads back to the central column, where more elevator stops await. You end up moving up and down floors going through these side stations looking for the right path to reach that central column again and return home to unload your treasure/materials, hand in quests and restock your equipment.

What was an irritating journey into the unknown before has now become another facet that I've come to appreciate about the game. Let It Die is full of these instances, which is why it's been such a slow burn for me. I hated the focus on item durability, but learned to appreciate it because it forced you to jump between different weapons and study each one's role in combat: even the humble fireworks gun is a serious ranged weapon if you buy an upgraded version from the store and have enough mastery levels, and there's a few enemies you'll want to fight at a distance. I hated the music, but turned around on it fairly quickly once I realized how well it fits the metal/punk aesthetic the game's going for - like a post-apocalyptic roguelike version of The Warriors - and there's a few tracks, like Survive Said the Prophet's "Let It Die" (a lot of the band music has songs named for the game's title for whatever reason; I'm hoping these are all Indie acts commissioned to make music for the game, possibly by Suda directly) a.k.a. the theme for the Jackals, that are now among my front-runners for this year's "best soundtrack" considerations. I hated the game's antagonistic online and its always-on PvP features, but then began to accept how that too is part of the game's central coda of letting things go: money and "SPlithium", the game's shop currency and upgrade currency respectively, are so quickly gained and spent that it's no huge deal if someone robs your waiting room while you're away. It's not nearly as irritating as getting cleaned out in MGSV would be, though I've yet to reach the point where I need a huge amount of jealously-guarded resources to upgrade. I hated the easily-reached low level cap for Fighters, but relented after learning that the caps get raised after every boss and this is simply a way of making the game's challenge level stay stable.

As a result of these epiphanies, and after spending more time with the game, Let It Die has been slowly climbing my GOTY ranking list. I don't know how much more of it I'll play this year - as stated in the intro, I've got a few new games to check out tout de suite - but it's definitely grown on me. And all this from a F2P game, no less. I've presently left the game at the penultimate floor before the first major boss of the game, so that's going to be the one remaining goal for Let It Die I intend to complete. If nothing else, I'll want to hop back in occasionally to see what they've added: if a crazy new Suda51 character shows up in the waiting room to enable a whole suite of features, I'll definitely want to meet them.

Log in to comment