"This Is Not A Game."

By Little_Socrates 43 Comments

This is a long one, folks. So first, a video.

This Is Not A Film debuted at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival after being smuggled out of Iran on a flash drive. It's got a 100% on Rotten Tomatoes, and I found it one of the most boring and miserable filmgoing experiences of my life. Walking out of my college's union theater Thursday night, I felt I had gotten more out of About Cherry, a movie only notable for being the exact opposite of Boogie Nights and for containing the nude breasts of the girl from Chronicle. Needless to say, I disagree with This Is Not A Film's 100% rating.

However, I now find it an extremely useful weapon in the fight for narrative-driven games. Luckily, the thumbnail for the trailer centers on the exact line that is circling my brain today;

"If we could tell a film, then why make a film?"

The Walking Dead has just won the Spike Video Game Award for Game of the Year, along with a smattering of other category victories. People are now lining up because they are faced with the reality that The Walking Dead, a game they've chosen to dismiss entirely as "not a game," is liable to win not just the VGA for Game of the Year, but also several more Game of the Year awards, in direct contrast to their nominations of XCOM: Enemy Unknown, Crusader Kings II, and Far Cry 3. Shane Satterfield of GameTrailers is trashing the VGAs for nominating Journey and The Walking Dead, and yet goes on to point out how much he loves Journey, intentionally omitting praise for The Walking Dead. Our own users are questioning whether or not TWD is a game regularly.

This blog will not be particularly original in format. In fact, it pretty much owes its structure to This Is Not A Pipe, a blog by jbauck that brilliantly approaches disappointment with the Mass Effect 3 ending. At some point, I suggest you read it, as it's been part of a long healing process that is causing me to absolutely adore Mass Effect 3.

But, for a moment, let's return to This Is Not A Film.

The "movie" centers around two directors sitting around a house and making a rogue "not-film." The lead director, the one who "acts" throughout most of the trailer and movie, is under house arrest, will probably go to prison, and has been banned from directing or writing films for twenty years. So, he decides it'll be okay if he acts in a movie by another director, and decides to try to read through his last script to give a glimpse as to what his movie would be like. However, he gives up at one point, asking:

"If we could tell a film, then why make a film?"

The next five or ten minutes or so centers around the explanation behind this line. It's easily the best sequence in the documentary, and it's the only reason I haven't written an inflammatory rant questioning how this film is so beloved instead. In essence, by showing clips of his previous films, our lead director explains that the independent director is a more adaptive personality, responding to what he's been given. He shows a clip of an amateur actor who is offended at a jewelry shop, and explains that he'd have never intended to ask his actor to become so deliriously upset, but instead he wound up with an intensely human reaction that is shockingly empathetic. In essence, the amateur actor becomes the director; because the director doesn't know what the amateur will be able to do, the director has to adapt to the amateur's skill set and work to focus on their strengths. Next, he shows a clip of a woman running through an airport; here, the location is director. The repeating parallel vertical lines moving quickly enhances the tension of the scene, but the woman's face is invisible behind a veil; there isn't really any acting happening here, no "particular face" that the actress needs to wear. Here, the director acquiesces to the location and uses its strengths to enhance his vision.

A film is too much more than words on a script; it comes to life through its actors and its locations, and the director simply gives a lens through which to view them. The director gives up in outrage. How can he tell a film without any actors in his apartment?

Back To Games

We all acknowledge that there's a lot of reasons people play games. Quickly, let's break out some of the clichés: to have fun, to escape, to view art, to simply "enjoy", to hear meaningful and modern stories, to spend time, to socialize, to see a creator's expression, to challenge themselves, to grow, to see technical achievement, to replicate a real-life goal, etc.

Ultimately, interactivity isn't even inherently subject in those goals. Several people enjoy the stories of games, socialize, or have fun with games by watching Let's Plays on YouTube, or Endurance Runs here on Giant Bomb. That experience is not a game; it is a viewing of entertainment media, more similar to television or film than playing a game. Think "This Is Not A Pipe" here.

But the subject in question is still primarily a game, and so the Let's Play is a representation of a game, an abstraction of the playthrough of a game. This becomes immediately obvious when one tries to watch, say, a playthrough of Sam & Max Hit The Road on YouTube, and the player barely bothers to talk to the Woody Allen fisherman character I would have absolutely showered with clicks in order to hear all his dialogue. I am not playing the game, but simply watching the game does not remove me from the experience of playing all the same.

Let's Plays inherently put us in a sort of game-playing limbo between playing and not playing a game. We are obviously not playing a game, but we may be playing with the abstraction all the same. When one watches a Let's Play, you're often engaging with the game on a metainteractive level, saying "I would have chosen to do this" or "NO, YOU IDIOT. IT'S RIGHT THERE! I ALREADY SAW THE SOLUTION! GOD!" But in that moment, especially in a puzzle game, you are still interacting with the game.

Therefore, interactivity is less defined than simply pushing buttons to make things change on the screen. Heavy Rain is a strong example. Its Quick Time Events and wonky controls definitely help to define Heavy Rain as a game, although the story does indeed adapt slightly if a character chooses to encounter a situation a specific way. The "game" of Heavy Rain, however, is really in its mystery; who is The Origami Killer, and can you deduce it before the game reveals itself? That's ultimately why the plot of Heavy Rain is such a betrayal; the ultimate reveal is too implausible, thematically unsatisfying, and just plain unreasonable to ever satisfy the "metagame" of Heavy Rain.

Enter The Walking Dead.

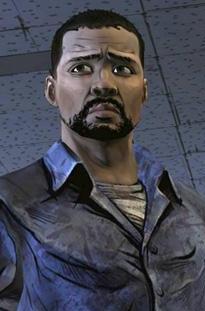

The Walking Dead is a prime example of a game that engages us more with its narrative elements than with its gameplay. It is a game that can be experienced with another player's hands on the controller, so long as you are in charge of Lee's decisions, and it can be emotionally affecting without that control as well. The "metagame" of The Walking Dead, of course, is about choice and the characterization of Lee. Similarly to Mass Effect, Lee is only a shell if you choose to allow him to be one, and if Lee is a robust and dynamic character, it is because The Walking Dead gave you the tools and relationships necessary to shape him into the character you want him to be. He can be a petty survivalist or an altruistic communal thinker, a leader or a wilting flower, a kind but troubled man or a distant and forceful ex-convict.

Shaping Lee is, in my opinion, the primary gameplay mechanic of The Walking Dead, and the secondary mechanic is considering your options when there is no good option. Imagining the next result is a more vital part of The Walking Dead than mashing the Q key to avoid getting eaten by a zombie. And deciding whether or not Lee is a good father based on your own choices and responses to questions is more essential to The Walking Dead than taking the belt off the generator to get a look at the barn.

This is not satisfying to a lot of players, obviously. The argument will probably rage for weeks now as to whether or not The Walking Dead deserves to be a game, or, beyond that, if it's any good. In "This Is Not A Pipe," jbauck effectively divides the responses to the Mass Effect 3 endings into four separate categories, using Robert Frost's " Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening" as a baseline for these responses. Using this same idea, responses to The Walking Dead can be broken down into several categories:

1) It's an emotionally affecting poem that allows you to pour yourself into its well.

These are the people who have adored The Walking Dead and feel they understand its purpose. To them, the game is about shaping Lee and his relationships with other characters, as described above. Maybe they're new to adventure games, or maybe they've been playing Myst, Monkey Island, and visual novels for years. However, they have trouble understanding how The Walking Dead could have ever lost. To these people, the victory of The Walking Dead is encouraging.

2) It's definitely a poem, it doesn't have to rhyme to be a poem. You're all a bunch of knob-eaters.

These people have been championing interactive fiction for years, or understand the history of games. They already know that an adventure game and a visual novel totally count as games, at least in their eyes. They are people like Jeff Gerstmann, who @MattyFTM has done a good job quoting in respect to this issue. Here's the quote, which pretty effectively summarizes the argument.

@MattyFTM said:

"There’s really no need to maintain such a narrow view of gaming. The answer to the question “what is game?” changes every year. If you disqualify The Walking Dead now, would you disqualify Monkey Island back in 1990? Zork in 1980?

All of those games fall on slightly different spots on the play-to-watch scale, I suppose, but to say that The Walking Dead isn’t even a game is a bit much.

Instead of worrying about what gaming is or isn’t, focus on what you like about games and why. It’s perfectly OK to think that The Walking Dead is lame, boring, or not for you. But to go all the way to the end and start saying that it doesn’t even fit in the same category as other, “real” games starts to feel a bit elitist, right?"- @Jeff Gerstmann, doing a better job of answering this post than I ever could. Via his Tumblr.

This situation is frustrating to this group of people, because this shouldn't really be an argument. To these people, the victory of The Walking Dead is reasonable.

3) This poem isn't very fun to read. This guy seems depressed, and why is he hanging out in the cold?

These people play games for some form of enjoyment, either narrative or gameplay-wise. While most will champion gameplay over narrative, they will also fall in line and agree that Uncharted 2 was one of the best games of the generation because it was so much goshdarn fun. Gameplay is generally central to the argument for "fun" by these people; the gameplay must be at least serviceable to carry a fun story, and fun gameplay can cause players to completely ignore a dumb story. For this group, The Walking Dead isn't just mostly unenjoyable, it's almost threatening to think it might supplant the kind of games they enjoy. To these people, the victory of The Walking Dead is terrifying.

4) Wait, I thought this was a short story competition.

These people feel they missed a memo in which games like The Walking Dead were suddenly being considered Game of the Year nominees. Maybe they weren't playing games at all during the heyday of adventure games, but suddenly they find themselves surrounded in a revival. The Walking Dead's support is so universal as to be confusing. They might ask, "don't we usually try to find innovative gameplay mechanics and technical achievement to give this award? This game only has QTEs and massive technical bugs. And what makes this so different from Mass Effect, anyways?" Some of the people have played TWD, and others have not. To these people, the victory of The Walking Dead is baffling.

5) Maybe it's technically a poem, but the part everybody enjoys is the author's biography.

These people understand that The Walking Dead has quicktime events, puzzle-solving, and action sequences, but didn't find that they enjoyed any of them. This group argues that The Walking Dead's strength is in its narrative, which we've come to learn does not change a whole lot from playthrough to playthrough. While they may or may not have ultimately found The Walking Dead enjoyable, it's not for the reasons that they consider a game the best medium in the first place. To these people, the victory of The Walking Dead is frustrating.

6) Poems aren't as good as novels. Why are you wasting your time with this drivel?

These people don't take video games all that seriously. They're fun, sometimes they're emotional, but ultimately, they're entertainment. A game having an ultra-serious narrative as its big plus seems completely silly to these people, as they'd rather have spent the twenty-plus hours playing The Walking Dead or an RPG just reading a good book instead. To these people, the victory of The Walking Dead is trivial.

The conflict arises from the distance between arguments 1 and 6. The people who fell into the first category (also, those liable to give it a Game of the Year Award) absolutely value the types of stories a game can tell, while the people in the sixth category absolutely do not. The range of opinions in the middle definitely show that The Walking Dead is obviously not a binary experience, but it's the distance between the two extremes that will allow for so much dissent and disagreement about the game in general.

Personally, I find myself in the first two categories. I really enjoyed The Walking Dead, and I'm a bit frustrated that people don't want to consider it a game. But, rather than simply let this end with me preaching more than I already have, I'm going to play devil's advocate and try to posit arguments from the dissenting sides. I feel that I emotionally resonate with each and every one of them, and so I'm going to discuss The Walking Dead from both sides. Let it be known that I do really like The Walking Dead.

And, perhaps most importantly, there will be spoilers from this point out if necessary. You should really finish The Walking Dead.

Now, then, let's begin.

It's Terrifying

Games are in a weird place right now. Retail releases have largely been considered disappointing this year, with the only standout favorites being Dishonored, XCOM: Enemy Unknown, and Far Cry 3. The downloadable space is getting huge, and I have a feeling there'll be hardly a person out there who doesn't have at least one downloadable game on their Top 10 lists this year. And the downloadable space is getting weirder; while art pieces like Journey and The Walking Dead usually lose out to games like Mark of the Ninja and Bastion, they seem poised to win most Downloadable Game awards this year. Hell, Tokyo Jungle, Fez, and Dyad all came out to critical acclaim this year.

So, what's going on? Obviously, a lot of major 2012 titles got pushed to 2013, BioShock Infinite included. And there were several disappointments in the retail space, including Max Payne 3, Assassin's Creed III, and Resident Evil 6.

But I think indie also got bigger, and it continued to get weirder. Articles like @patrickklepek's Worth Reading have pushed games like Frog Fractions and dys4ia far beyond their normal exposure. People are looking for more personal and artful experiences, and "fun" is sometimes falling to the wayside in the search for "art." Papo & Yo was perhaps one of the most divisive games of the year for this reason; some found it artful and resonant, and others found it dull and trite.

But the entire conversation is terrifying for those who just want to have some fun. Do games really have to always be this serious, all the time? Can't we reward Far Cry 3 for being a brilliant play experience with awesome gamefeel, even if it's tone deaf to its misogyny and primitivism? Rewarding The Walking Dead seems like a step away from what games used to be. Hell, games are already running from it constantly; analysts won't stop saying we'll be playing all our games on phones in ten years. It's easy to imagine the VGA judge from Entertainment Weekly having only played The Walking Dead on their iPad, even though we should probably logically know better.

Giving The Walking Dead Game of the Year isn't only unsatisfying because these people didn't get much out of it, it's a signal of the downfall of the thing they've come to love for so long.

It's Baffling

Okay, I'll be straight here; I don't think The Walking Dead is the best game of 2012. My last blog was about how the game is technically broken. I think it's got narrative issues, and its Episode 5 solutions for dealing with Kenny can be unsatisfying and cheap. Episode 1 is not especially good to begin with. Episode 4 is light on a lot of content, and Episode 2 is barely connected to the rest of the story. The emotional watermark of Episode 3 is a high one, but I really don't think it's enough to mark TWD as Game of the Year.

So I understand entirely where these people are coming from. They want a game to win Game of the Year, and preferably, it's a game that comes in a box from a store shelf. Smaller, bite-sized experiences can't compete with the vast expanse of a game like Far Cry 3 or Borderlands 2, especially when they're narrative-focused. This is where Shane Satterfield sits; this is where a whole lot of people sit with him. The idea of an adventure game or visual novel ever winning Game of the Year is baffling; even in 1990, Secret of Monkey Island can't compete with Super Mario Bros. 3, and there's never been a point where they've stood out as the best title of a given year.

Granted, a downloadable still has a shot with some of these people. You can jump and play online in Journey; Fez's gameplay is the primary mechanic; FTL is pretty much all-game, all-the-time. But The Walking Dead doesn't really deserve that kind of support, and they're confused as to why it's really even part of the conversation.

It's Frustrating

The Walking Dead is full of quick-time events, mediocre puzzle-solving, and middling-to-bad action sequences. It can be a bit frustrating to play. And therefore, why should it win Game of the Year?

Well, as I've discussed above, I don't think the primary gameplay mechanic of The Walking Dead is the part where you mash the Q button; I think it's the part where you decide who Lee is going to be.

Unfortunately, I can't relate to this side because, in this case, I feel the opposite is true. I play table-top roleplaying games with no combat mechanics because I think there is a game to creating a character and telling a story, even if it follows a pretty established narrative.

But I realize that most of what I've written in that regard probably sounds like hogwash to someone who disagrees, and I empathize with that. I feel the same way about someone trying to explain to me why XCOM: Enemy Unknown's base building elements are successful and how the tutorial for those parts is even remotely acceptable, or someone trying to explain to me how good The Ocarina of Time is. I offer you the chance to reject my writing because it's reasonable to reject a game or an opinion. And if you reject the perception that The Walking Dead's gameplay is metacontextual, then yeah, the gameplay is kind of rubbish, and it's absolutely undeserving of an award.

It's Trivial

I approach television with largely the same lens; in the time it takes me to watch one season of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, I could read House of Leaves all the way through. You want me to watch, like, ten seasons of a TV show to hear one story? Sorry, but I'm not sorry. I'm out.

Of course, there are exceptions. I'm watching Breaking Bad because I also find it entertaining. Twin Peaks is short and sweet, and Firefly is lucky it's only one season long.

But this approach is thrown around a lot with games, and it does tend to make me sad. I mean, I've spent 300 hours with the characters of Persona 4 over my own playthrough and watching other people play, and it's probably been the most intense relationship I've felt with a piece of fiction. Metal Gear Solid 3 grabs me in the same way. The stories of video games can definitely be better than books regarded as "the best books."

The question, however, lies in the time commitment. Again, the time it took me to play through The Walking Dead's season is equivalent to watching ten movies. Will The Walking Dead's five episodes ever compete with the experience of watching, say, Citizen Kane, Vertigo, Apocalypse Now, Alien, Star Wars, Blade Runner, Casablanca, and Seven Samurai?

Well, actually, no. But only because they're playing different sports.

"If we could tell a film, then why make a film?"

Longevity is the advantage of episodic media. The Walking Dead's significance may well be lost as a marathon, I'm not sure. The large advantage of The Walking Dead's episodic format were the months we'd spend waiting between episodes after each cliffhanger. It caused us to attach to the characters when we weren't even playing; take a look at the #ForClementine hashtag for evidence of that happening to several players.

This does happen over the course of a non-episodic game of considerable length, too. If somebody tells me Xenoblade Chronicles is their favorite game of the year, I'd say "I certainly hope so." Because if you put yourself through that roughly 120-hour game without ever emotionally attaching yourself to its characters, you have fucked up. Sequels can do this too; Mass Effect is the obvious example, although the ending is exceptionally controversial in that regard.

But in episodic media, the waits are built-in, expected, and breathless. I'll make a comparison to yet another previous blog; my blog about Slendervlogs. I talked a lot about what made Slenderman "scary" inherently, but I missed perhaps the most important element; we're always watching for him. You see, when you spend three years watching a series where he can show up at literally any moment (and, when they're good series, he doesn't,) it starts to creep on your mind. I've seen him over the last year in a hospital, a school, a forest (obviously), an airplane, people's homes, etc. He's basically been everywhere I could possibly be afraid of him, and he's been on my subconscious for the last year or so. That is what makes him scary; the fact that when each entry stops, he only goes away until I next see him.

And by "I next see him", I do mean "I." You see, those videos are first-person found-footage videos almost exclusively; that immerses the viewer in the experience, as we're all aware. It changes the subject to the viewer, and that increases the terror tenfold.

That is what makes The Walking Dead's format effective; by involving the player directly, it can keep us personally involved in the character of Lee, and his relationship with Clementine. But the longevity kept us always thinking about our responsibility to Clementine, waiting with baited breath for the next episode to be announced.

The Walking Dead would not have succeeded as anything other than an episodic game, and it cannot be helped that The Walking Dead is a stepping stone in the narrative of games.

Little_Socrates is also known as Alex Lovendahl, the host of the podcast Nerf'd. Little_Socrates is also working on his Game of the Year awards, which will be posted on Giant Bomb in the coming weeks!