Indie Game of the Week 236: Super Win the Game

By Mento 1 Comments

Look. I know. I know I play a lot of these explormers. I know I have to keep linking the word explormer to the metroidvania page because no-one would know what I'm talking about otherwise. It's become a well practiced routine here in Indie Game of the Week Central. And yet, I couldn't help but find myself with a huge stack of these map-traversal types and I'm never not in the mood to play one. So here we go, this week's explormer is Super Win the Game: a commercial sequel to the freeware game You Have to Win the Game, following similar simple-directive Indie games like You Have to Burn the Rope that end up having some additional surprises in store.

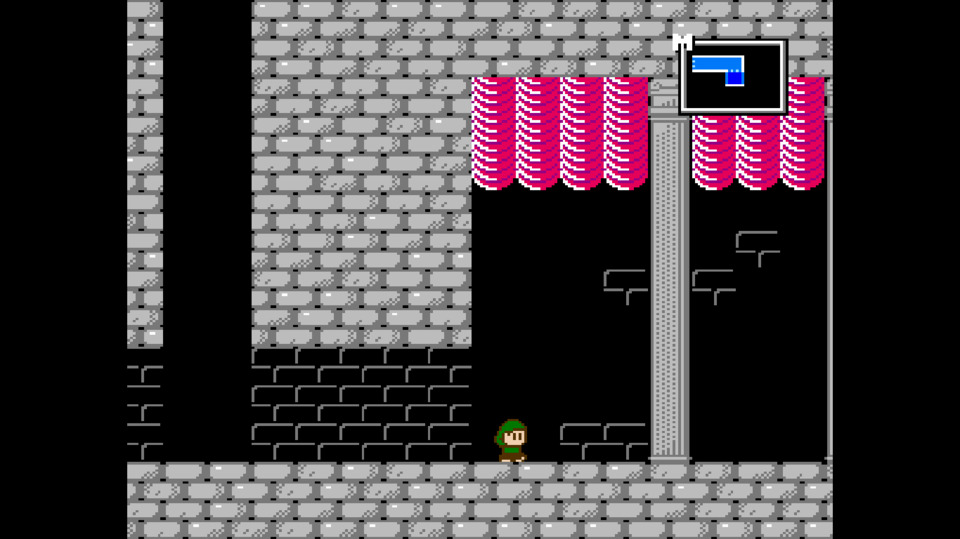

Naturally, the more explormers I cover the more I'm drawn to what's different about them. Super Win the Game is superficially straightforward enough: it has a specific 8-bit style overtly modeled on the second Legend of Zelda game, Zelda II: The Adventure of Link, but plays like a standard platformer with zero combat and, initially, not a whole lot else beyond a single jump until you find a few upgrades. What intrigued me first of all is that it has an overworld map: not the most common sight in an explormer game, even for those that delineate zones as separate areas to explore. It's another aspect it borrows from Zelda II as well, which means there's plenty of secret nodes hiding in conspicuous single-tile forests or along the furthest contours of the geography. The dungeons are big on secret areas too: there's plenty of secret walls to feel your way through, and it's easy to overlook barriers like pools of acid or lava until you suddenly find an upgrade that lets you swim through caustic fluids and are left trying to recall the areas in which you passed over them.

Other Zelda II flourishes include a dungeon key feature that gives you some options if you're not eager to find all them in the wild - you can buy them individually, you can borrow them at astronomical interest rates, or you can just buy a skeleton key that ensures you never have to worry about locked doors again - and a collectible currency by way of gemstones. Each region mercifully tells you how many gemstones there are to be found in the current map, as well as map icons if you happened to pass by one. Beyond that, it's mostly poking your nose into dungeons, finding some new upgrade, figuring out where else in the wide world you can go with this new upgrade, and maintaining that loop until the end-game when you need to find six heart fragments to restore the kingdom's cursed monarch. Up to that point, the game offers a free fortune teller service to point the way, but finding the heart pieces is left to the player's own resourcefulness and ability to take notes from hint-offering NPCs in the various villages and nooks across the world map. The game does a fine enough job replicating the mystery inherent to the first two Zelda games without necessarily being too obtuse for NES nostalgia's sake. No trying to figure out what the hell "a graveyard duck" is supposed to be, for instance.

The gameplay, for being no-frills, is as responsive as you'd want with traversal upgrades adding much to your ability to whiz through areas you had to take slow and steady the first time through. A double-jump naturally helps a lot, as does a way of ensuring bodies of water can be explored instead of instantly fatal, but it's a wall-climbing glove that really makes it easier getting around places. Each wall-jump resets your double-jump, so with enough finesse you can triangle-jump your way up even arched ceilings to find out what lies above. Most dungeons need to be visited at least twice to explore everywhere within, not to mention acquiring all the collectibles, and some may in fact have more than one traversal upgrade. The challenge level is just right for an 8-bit throwback too: you'll probably rack up a death count measured in the hundreds before the end, but frequent checkpoints and fast resets ensure a minimum of frustration. It's not a huge game by any stretch but it felt like there was plenty to explore at all times, and the end-game heart piece scavenger quest relied upon all the skills I'd been taught so far and the familiarity I'd gained with the world and its various themed regions.

Finally, the game has a certain surreal undercurrent that could've been explored in a little more detail. At the end of every dungeon, usually just after the traversal upgrade, is a magic book you can read: they serve to warp you to the start of the dungeon as a convenience, but prior to that each one will first teleport you to a black-and-white realm of the unconscious where the game briefly becomes a bit meta with its commentary, with each of these smaller dream realms playing with the level design in some odd ways. An example would be a corridor where the surrounding walls eventually melt away to nothing but a black hallway before it spits you back out into the real world. An alien race of helpful advisors that call themselves Arcadians are said to have first come to the planet through these liminal spaces of thought and mind and found themselves trapped, and it leaves a slightly surreal subtext to the game's otherwise standard minimal-plot video game tale of a wandering heroes, evil wizards, and cursed kings. It's not significant enough to factor into the game much - there's no post-game business where you're breaking down the reality of this 8-bit pocket universe or anything - but it's a theme that the developers explore again in Eponymous, based in an empty Minecraft-like world.

Super Win the Game is fairly standard as far as Indie explormers go, though given it was released in 2014 when they weren't quite as ubiquitous as they are currently I'm willing to give them some slack. Its use of an overworld map and discrete zones to visit (and revisit) does provide a distinction over its more common contiguous-world peers at least - there's precious few stage-based explormers out there, including the likes of Order of Ecclesia and Demon's Crest - and while basic the platforming is smooth and concise and aided ably by the slow trickle of traversal upgrades. I think it has been left behind in the dust by several subsequent years of imaginative and elaborate evolutions to the genre, now that explormers have to do more than ever to set themselves apart over the competition, but I found its modest charms to be the tonic I needed between larger playthroughs. (For what it's worth, after finding all the gemstones, I super won this game.)

Rating: 4 out of 5.

| < Back to 235: OPUS: Rocket of Whispers | The First 100 | The Second 100 | > Forward to 237: Brigador |