Indie Game of the Week 239: The Magic Circle

By Mento 1 Comments

Seeing the discourse around the recently released Axiom Verge 2 - surprise, surprise, I'm fascinated by yet another Indie explormer - reminded me of a Quick Look for a different Indie game with an interesting approach to subtly changing the game world by essentially hacking into its base code, from changing an enemy's health value to its core abilities and behavior. The Magic Circle, released by Question back in 2015, is a game about game development. In particular, it's about a studio that has let perfect become the enemy of progress: this studio eventually scrapped their '90s space-faring FPS for the sake of a fantasy adventure-RPG, but is no closer to finishing that project either after almost two decades of development. The staff is in something of a chaotic state - the director hems and haws over every decision, the head level designer is trying to get herself fired since she's unable to quit for contractual reasons, and a new recruit with an obsessive love for the developers' prior games is planning a Machiavellian gambit to bequeath these never-to-be-finished projects to the fanbase to complete. However, the player character is none of these people. In fact, it's a big question who the player actually is: they're treated as a nameless playtester, but it's evident they have more control over this incomplete world than they should.

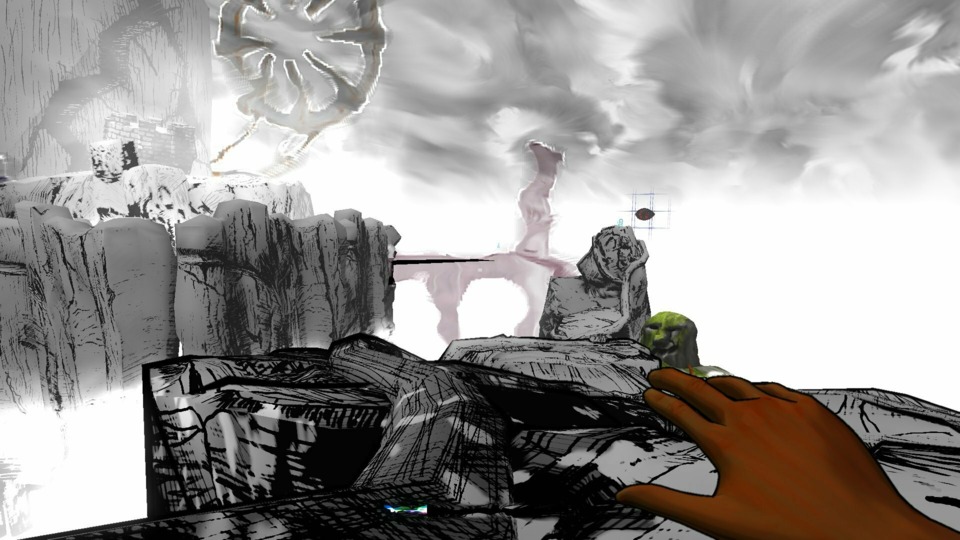

The game's title has a double meaning: the fantasy game-within-a-game (and the sci-fi non-entity that preceded it) is named The Magic Circle for lore-related reasons, but the Magic Circle is also a real-life association of stage magicians whose first and only rule is to never reveal what's going on behind the curtain or under the hat. You, however, will see every line of code and every asset, active or temporarily deleted, as you explore the Magic Circle's fragmentary and (mostly) monochrome setting. After a brief intro, you're dropped into an open-world to explore methods to get the game closer to a complete state, but first you need to work your way through and over a number of obstacles and broken bridges (literally, in one case). Given a set of developer tools, you do this by changing the behavior of wandering monsters and other objects. A rock, for example, comes with the fireproof behavior: you can pull this behavior from it and make something else fireproof instead, ideal for crossing the river of lava blocking the volcano. Monsters can have their allegiances changed in order to target whichever foe is in your path (or just stop them attacking you) and you can even choose to upgrade a companion creature by powering up their stats or changing their attack patterns to something more powerful: a meagre cyber-rat becomes a little more formidable when given a Securitron's railgun or the fire breath of a flame elemental.

In the midst of all this code tinkering, you're picking up bits of lore not from the game world, which seems to be barely formed even after 20 years, but rather that of the studio behind it and its unfortunate past. The studio founder Ishmael Gilder - voiced to sardonic and delusional perfection by James Urbaniak, formerly of The Venture Bros. - created a compelling world way back in the text adventure days but seemingly has no idea how to translate his ideas and stories to a modern 3D action game and has long since lost his verve for this line of work and the fair-weather fans that seek to demolish any carefully-built world for their own amusement, and while the eager new recruit Coda appears on the surface to be a breath of fresh air for this struggling studio she plans to sabotage the game and depose its director for the sake of some misplaced fan entitlement. Maze, the lead level designer, is more savvy about Coda's schemes but has her hands tied after years of answering back to the boss due to him dragging his heels about implementing a multiplayer mode, and at this point no longer cares either way and is looking for an exit. All this dev drama is made apparent as the player digs into audio logs and visual files, many of which are purposefully hidden in glitchy assets, giving the player reasons to explore every nook and cranny beyond picking up new behavior protocols to exploit - these logs more or less explain why the Magic Circle is stuck in the state it's in and comprise the meat of the game's storytelling.

My first concern with any game involving programming (or in this case scripting, and yes there is a difference) is whether or not they make it simple enough for the player to understand. I've done my fair share of scripting in the past and the parser used in the game is considerably easier to use than the real thing - it's intuitive too, which is more than can be said for most programming tools - and there's often multiple solutions to problems in case your brain happens to work differently. For instance, there are these enemies called "flamers" that need to be removed because they're guarding bridges, though you can't edit their behavior directly because their flame attacks tend to demolish your avatar before you get close enough to use the tools on them. Instead, you can either program an ally to have a powerful ranged attack to eliminate them all from a safe distance, or you can give that same ally the fireproof status from those rocks I mentioned to let it safely melee them all to death as they try in vain to roast it. When you finally find a monster capable of flight, you can then use a combination of a flat creature (the rocks will do - they're much more versatile in this game than in others) and the waypoint tool to ride them around as your personal hoverboard and overcome a lot of hazards that way. The game's not particularly long and doesn't have too many of these puzzles to solve, but it fills what geography it has with enough incidental storytelling and surprises to make it feel much more expansive. The endgame too goes in a completely different direction, albeit in a fashion germane to the themes of the game.

The Magic Circle is an unconventional game that can be a little too meta for its own good on occasion, though like similar games about game development - The Beginner's Guide and There Is No Game: Wrong Dimension, both of which I've yet to try, and to some extent Baba is You - there's a subversive and almost self-defeating streak about trying to convey the countless difficulties inherent to creating a piece of interactive media that would resonate with a wide enough audience to justify the cost of making it. Its message is less some "woe is me" artist kvetching or about how toxic entitled fans are ruining the joy of making games (there's a few jokes about both however) than it is shining a spotlight on the unique challenges faced by those in game development that mostly go unknown by those embracing the final finished product. The Magic Circle heightens the drama and comedy alike of this process by envisioning a studio truly stuck in developmental hell: its visionary leader stymied by indecision and embitterment while his many subordinates fret about the future of the game and their careers both. While the real thing is rarely as tragic, there's a sense that any project might stretch on for eternity given the right (or wrong) set of circumstances and it takes almost a literal deus ex machina by way of the player's unpredicted interference to finally push the project over the finish line. While its true appeal is in that comedic exaggeration of how the game industry can be a merciless taskmaster to amuse those who closely follow in-progress game development and regularly partake in betas and fan mods, there's enough clever puzzle design and dark workplace comedy to enjoy for those less invested in that world.

Rating: 4 out of 5.

| < Back to 238: Batbarian: Testament of the Primordials | The First 100 | The Second 100 | > Forward to 240: Symphonia |