Overview

Visual novels are a sub-genre of Japanese adventure games and are a form of interactive fiction. The genre is similar to a mix-media digital novel where the focus is mainly on reading text. The presentation of visual novels is usually made up of character portraits on top of background images accompanied by music, sound effects and sometimes voice acting. Some titles have no gameplay whatsoever and simply involve reading a linear story. However, it is more common for visual novels to have branching narratives where the player can experience different routes in a story and obtain different endings by making choices, very similar to Choose-Your-Own-Adventure novels or Gamebooks. The genre originates from the Japanese game industry and has seen the most activity on open platforms like the PC but is also prevalent on home consoles and portable devices. In Japan itself, the genre is often classified as "novel games" or simply "adventure games," due to it being a sub-genre.

Origins

During the 1980s the adventure genre grew and evolved in Japan. Over time, some titles began to be released that focused more on reading instead of traditional puzzle solving. Early magazines sometimes classified these adventure games as "storybook" or "gamebook" style titles [17]. There were also many adventure games released for early CD-based consoles that were marketed in Japan as "digital comics" due to the fact that they focused more on storytelling [19]. However, one of the first companies to specifically label their titles as gamified "novels" was System Sacom with their Novel Ware franchise in 1988 [17].

While the idea of a story-focused adventure game had existed in Japan for years, the series that truly popularized the "novel game" concept was Chunsoft's Sound Novel franchise. The series began in 1992 with the Super Famicom release of Otogirisou and later gained mainstream popularity with 1994's Kamaitachi no Yoru (also known as Banshee's Last Cry) [5][7][15]. The way these games focused on reading and branching narratives inspired the creation of many imitators on consoles like the Super Famicom and PlayStation.

However the word itself, "visual novel," was created a few years later when the genre moved to Japanese computers thanks to an adult video game developer named Leaf. Released in 1996 for the NEC PC-98, Shizuku was an erotic horror game marketed by Leaf as the first volume in the Leaf Visual Novel Series, coining the word "visual novel" for the first time [5][7][8][15]. Playing off Chunsoft's own brand name, the developer's goal with Shizuku was to create a title similar to Kamaitachi no Yoru for the PC market, since that style of game had been exclusive to consoles at the time [16]. However, the creators classified their game as a "visual" novel rather than a "sound" novel simply because the term "sound novel" was copyrighted by Chunsoft and because their game focused more on visuals [8]. Shizuku, and the other Leaf Visual Novel titles released afterwards, used detailed character portraits with multiple expressions and fullscreen event illustrations to visually punctuate their narratives. This was a stark contrast to the minimalist graphical style of most sound novels, which tended to focus more on audio presentation.

While the first two entries in this series were cult classics, Leaf's Visual Novel Series exploded in popularly within the otaku fandom after the release of 1997's To Heart, a romantic comedy about dating in high school. The genre then evolved to heavily focus on otaku interests and many companies in the late 1990s and early aughts began mimicking the storytelling style of Leaf's titles. Most notability a studio called Tactics began copying the format and presentation of Leaf's games with their release of MOON. in 1997 and One: Kagayaku Kisetsu e in 1998. Many of the developers at Tactics would eventually found Key in 1998 where they created other popular novel games that further grew the genre's popularity among otaku including Kanon, Air, and Clannad. Additionally, thanks to the emergence of free graphic engines like KiriKiri and NScripter, amateur creators also began using the novel template established by Leaf and Key to create their own doujin works. However, outside of Leaf, none of these companies or fans classified their games as "visual novels" with the notable exception being Type-Moon. This former doujin group labeled their early games, such as Tsukihime and Fate Stay Night, specifically as visual novels in the 2000s which helped spread the ubiquity of the term and popularity of the genre [5][9]. Over time, however, the term "novel game" began to be used by Japanese fans to collectively classify these novel-like adventure games while, in the West, the term "visual novel" caught on with English-speaking fans.

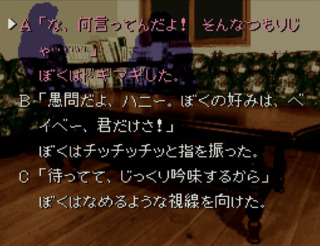

Kamaitachi no Yoru (1994) Kamaitachi no Yoru (1994) |  Shizuku (1996) Shizuku (1996) |

One: Kagayaku Kisetsu e (1998) One: Kagayaku Kisetsu e (1998) |  Tsukihime (2000) Tsukihime (2000) |

Japanese View on the Genre

While the term, visual novel, originates in Japan it is actually used far more often in the western gaming community than it is used in Japan itself, with the two regions having different understandings of the genre. Many titles that are thought of as visual novels in the West are classified as "adventure games" in Japan, with the abbreviations "ADV" or "AVG" often being used. Many popular titles that western fans would call visual novels, such as Clannad or Steins;Gate, are in fact advertised as just another type of adventure game in Japan [10][11]. Kotaro Uchikoshi, the creator of the Zero Escape series, explains in a 2013 interview that:

"The visual novel term does not really represent the genre in Japan. This is accepted as the genre and regarded as the genre outside of Japan, overseas. In Japan people think about it as... We have the adventure game, we have the sound novel, and we have the bishoujo genre. But there is no visual novel per say. With me personally, when I made 999, and Virtue's Last Reward, these are not referred to as visual novels, they're referred to as actual adventure games. Whereas overseas they're refereed to as visual novels. But in Japan, we don't really make that distinction [between visual novels and adventure games]" [6].

Jiro Ishii, director of 428: Shibuya Scramble, once elaborated that the adventure genre in Japan can be separated into two categories. These categories being traditional "command-based" and "novel type" adventure games [14]. Command-based titles allow the player to directly control their character through verb commands, or by other means, and require some kind of problem solving in order to continue the narrative. Basically, these games are structurally very similar to western point-and-click adventure games. However, "novel type" titles use the presentation of an adventure game to tell a story that does not require the player to overcoming gameplay challenges and keeps player interaction to a minimum [14]. Basically, command-based games are about "solving a riddle" while novel-type games are focused on reading a narrative. This novel-type of adventure game is what is often classified as a visual novel in the West or sometimes a "novel game" in Japan.

Western Definition of the Genre

In the West, the definition of a visual novel is vague and the word is often used as a catch-all term for various Japanese genres that don't have a strong presence in the English-speaking community. The term is usually applied to games based on their presentation rather than their gameplay or structure. Some of the commonalities shared between titles classified as VNs in the West are that they are text heavy, have an "anime" art style (or were developed in Japan), and are presented mainly through character portraits and text boxes [5].

Even Japanese titles that would be considered traditional adventure games are often classified by western fans as visual novels. These include titles released before the term was invented, such as The Portopia Serial Murder Case, and modern games like Ace Attorney even though the franchise's creator has stated that Ace Attorney is completely different from a novel game [18]. Additionally, due to the sub-genre's history in the eroge industry, western fans will often label any adult Japanese PC game as a visual novel if it has a large focus on story, even if the core gameplay is an RPG or something else. There is similar confusion with the dating sim genre where many visual novels that involve dating different characters will be classified as "dating sims" despite not containing any stat building.

There are also some western publishers and fans that think of visual novels not as a sub-genre of adventure games but an entire medium on its own. John Pickett, MangaGamer's Public Relations Director and Head Translator, explained in a 2011 interview that visual novels were their own medium that contained different gameplay genres within it, with the "novel" genre only being one of many [13]. The first American company to actually call their products "visual novels" was a publisher from the early 2000s named Hirameki International, who explained on their website that a visual novel is any game that involves "reading, listening, watching and choosing" [12]. None of the titles released by the company were classified as visual novels in Japan but they would label all their products as "Interactive Visual Novels" in spite of whatever they were called by their original developers, perhaps leading to many early English-speaking fans internalizing the company's loose definition of the term.

Gameplay

Visual novels are similar to "Choose Your Own Adventure" books, but take advantage of the digital medium to evolve the concept further. Common features of visual novels include branching storylines that lead to multiple endings with the gameplay often revolving almost entirely around the narrative. Gameplay is often fairly limited, and sometimes nonexistent outside of pressing a button to advance text, as the focus is placed primarily on storytelling. Actions are usually contained to simply making choices based on a selected number of options such as whether or not a character talks to a certain person, choosing dialogue responses, or deciding to move to another location. Making certain choices will often place the player on a "route" that will put the player on a specific story path that leads to different endings.

Because visual novels revolve almost entirely around storytelling and character interactions, this can allow narratives to be more non-linear. This is one of the key elements usually differentiating visual novels from traditional adventure games, where the plots are often more linear due to their greater emphasis on exploration and puzzle-solving. However there are also entries in the genre that eschew all forms of gameplay and tell completely linear stories while using the presentation of a visual novel.

Variations on the Genre

Otogirisou (1992)

Otogirisou (1992) Sounds novels existed before the visual novel term was invented, serving as the progenitor to what most people recognize as a visual novel today. The word was invented by Chunsoft in 1992 to brand their series of simplified adventures games but, even though the term is copyrighted, it is also sometimes used by fans to classify titles created by other developers that are similar. There is no significant difference between sound novels and visual novels in terms of gameplay structure but there are differences in how they present themselves. Sound novels usually minimize visuals, with the story's text being the main focus, and are known for relying more on audio design, with atmospheric sound effects and music being used to set the mood for the narrative.

Planetarian (2004)

Planetarian (2004)"Kinetic novel" is a term often used by western fans to describe a visual novel that does not have a branching narrative or any kind of gameplay. These are titles that focus purely on telling a linear narrative while using the presentation of a visual novel to deliver its story. The term originated from a brand created by VisualArt's called KineticNovel that was used to classify a line of linear visual novels, beginning in 2004 with the release of Planetarian. Western fans have since adopted the name to describe any kind of linear visual novel created by any publisher.

Hybrid Visual Novels

Utawarerumono (2002)

Utawarerumono (2002)There are some visual novels that are hybrids between two different genres with the two gameplay styles often being very segmented. This style of game was popularized by Leaf in the late 1990s with titles like Comic Party which contained novel-style story segments mixed with management sim gameplay. The Zero Escape series is also an example of a hybrid title where the puzzle solving gameplay and novel sections are very clearly separated. Other popular hybrid games include Utawarerumono, which has strategy RPG gameplay, the Baldr franchise, which has action mech combat, and the Spirit of Eternity Sword series among many others.

Sources and External Links

- Soundscapes – Back to Basics with Visual Novels, - by Peter Hasselström (Nightmare Mode, 2012).

- Visual Novels: Unrecognized Narrative Art, - by Alex Mui (John Hopkins University, 2011).

- The Weird World of Japanese "Novel" Games - by Ray Barnholt (1UP, 2012).

- Peter Hasselström: Can AAA games learn something from visual novels? - by Aare (Visual Novel Aer, 2012).

- ビジュアルノベルはいつ成立し、そして現在に至るのか? ストーリーゲーム研究家・福山幸司氏が解説する歴史 - by Koji Fukuyama (Game Business, 2019).

- Interview with Kotaro Uchikoshi, "The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Vol. 1" (Pages: 340-341).

- A Brief Introduction to Visual Novels by Matt Fitsko, "The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers Vol. 1" (Pages: 314-316).

- Bungle Bungle - The official website of Tatsuya Takahashi and Tooru Minazuki, creators of the Leaf Visual Novel Series.

- Type-Moon Offical Homepage (2004) - Classifies Tsukihime and Fate/stay night as "visual novels" on their Product page.

- Steins;Gate Official Homepage (2009) - Markets Steins;Gate as a "想定科学ADV".

- Key's Official Product Page (2004) - labels Clannad as a "恋愛AVG".

- What is a Visual Novel?, Hirameki International Group Official Website (2007).

- ANNCast's Interview with John Pickett of MangaGamer (2011).

- イシイジロウ氏ら第一線で活躍するクリエイターがアドベンチャーゲームを語り尽くす!――「弟切草」「かまいたちの夜」から始まった僕らのアドベンチャーゲーム開発史 (4Gamer, 2013).

- Otaku: Japan's Database Animals by Hiroki Azuma (Pages: 75-76) - Defines the origin of "novel games".

- TINAMIX INTERVIEW SPECIAL: Leaf's Tatsuya Takahashi & Woodal Harada (TinaMix, 2000).

- History and Origins of Novel Games (ADVGAMER, 2016).

- Capcom's Takumi Shū X Storytelling Ishii Jirō - Discussion on Creating Adventure Games (2015) (Gyakuten Saiban Library, 2016).

- Digital Comics Japanese Wikipedia Page

Log in to comment