The Dredge of Seventeen: November

By Mento 0 Comments

When it comes to game releases every year has its big headliners and hidden gems, but none were more packed than 2017. As my backlog-related project for this year I'm looking to build a list of a hundred great games that debuted at some point in 2017, making sure to hit all the important stops along the way. For more information and statistics on this project, be sure to check out this Intro blog.

After all that effort last month to get through as many remaining 2017 games as possible we're back to a relatively sedate offering here on November's The Dredge of Seventeen, working through a mere trio of games that are nonetheless solid contenders for the mid-tier that I'm sure many folks missed out on, my 2017-situated past-self included. They're all adventure games too, which I'm starting to think had as much of a banner year as the RPGs did. When I knock out December's entry some time around New Year's, I'm planning to break down all the games left behind; as I suspected at the outset, there's still so much left in the year that I couldn't quite accommodate in time. That includes big names like Metroid: Samus Returns, Cuphead, Snipperclips, Sonic Mania, Pyre, and so many others but also a huge number of games I'd never even heard about prior to researching this project back in January, and adding what I'd found to various wishlists (and shopping carts) as this year pressed on. That "late to the party" process accounts for two of the games presented here in this November entry, with the third only coming to my notice after covering its predecessor sometime in 2019.

It's given me pause for thought that - even if the intervening years haven't been quite as strong as 2017 on the whole - I'm sure similar scenarios apply to them as well: that there are simply too many franchises and corners of the game industry I'm negligent about following, left to slip through the cracks and denied their due. A reason if more were needed that Giant Bomb could use a few more staff members to extend its reach.

The Inner World: The Last Wind Monk

The United States is credited with establishing the point-and-click or graphic adventure game, being the home of both Sierra and LucasFilm, but it's Germany that kept the home fires burning after the genre all but disappeared from the mainstream after the FMV era of the late '90s. Since the genre's Indie insurgence, Germany has continued to have a significant presence in that arena with the likes of King Art Games's The Book of Unwritten Tales, Daedalic's Deponia, and Studio Fizbin's The Inner World. All three have a similar sardonic sense of humor influenced by Simon the Sorcerer, a UK-developed series that saw greater appreciation in Germany the way the US-made Wizardry and Lode Runner saw massive traction in Japan. Of those three, however, I'd only discovered the first The Inner World fairly recently: this February, in fact, when the first game popped up in the rotation for Indie Game of the Week. I'd then find out around that same time that its sequel was a 2017 release: one I quickly pencilled in for a visit with this feature before the end of the year.

The Inner World's titular setting is an inverted globe with limited illumination and no naturally produced air. Instead, wind is summoned through massive tubes running through the world's "underground" courtesy of a ruling class that can musically activate the tunnels with their nostril flutes to flood the world with fresh oxygen. It's an odd idea for a setting and one that the first game takes its time in delineating as it moves from one situation to the next along with introducing the protagonist, Robert, the last of the flute noses, his rebellious paramour Laura, her pigeon partner Peck, and the evil tyrant (and Robert's adoptive father) Conroy. As The Last Wind Monk picks up a few years afterwards, the first game is essential to understand the world, the lore, and how the events of that game have led to this sequel's present predicament. It also means, as a direct sequel, I can't talk about the story of this one without spoiling the previous.

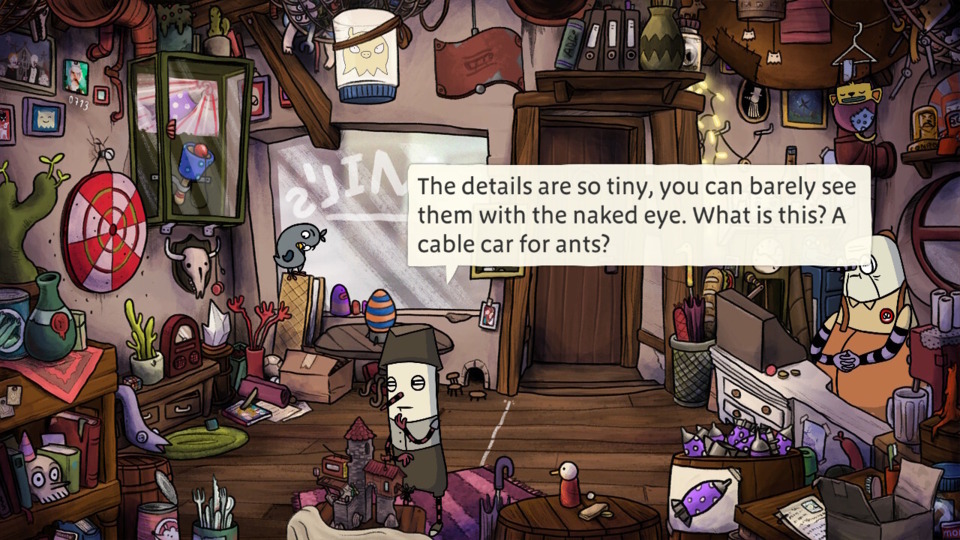

With that in mind, I'm just going to focus on the structure, puzzles, and script quality. Like many modern adventure games, Studio Fizbin took an episodic approach where each new chapter takes place in a new zone with new puzzles to solve and almost all the inventory is thrown out after moving on. That has the positive effect of reducing the number of active hotspots and inventory clutter as the game progresses, meaning it's that much easier to solve puzzles through trial and error if you can't get there logically in the manner the game intended, but the regular switching of venues also allows for a greater variety of puzzles. A persistent mechanic is the way Robert can learn songs to play through his flute nose, each of which has an affect on the world's hidden machinery: a song that makes platforms rise, for instance, or produces a strong gust of wind from any tunnels nearby. Different screens will have elements that these songs can activate, while in others they're irrelevant to the current puzzle(s). A new change to The Last Wind Monk is giving Laura and her partner Peck expanded roles, with both now playable in their own chapters of the story or together with Robert. Sadly, a lack of special abilities means Laura is often interchangeable with Robert when it comes to the puzzles themselves. Peck's a different story, however: though he cannot talk, he is able to fly and that means reaching items and hotspots that others cannot. All three share an inventory when together, though there's one memorable section in a monorail station where Robert and Laura have to figure out how to pass items back and forth while trapped in different rooms.

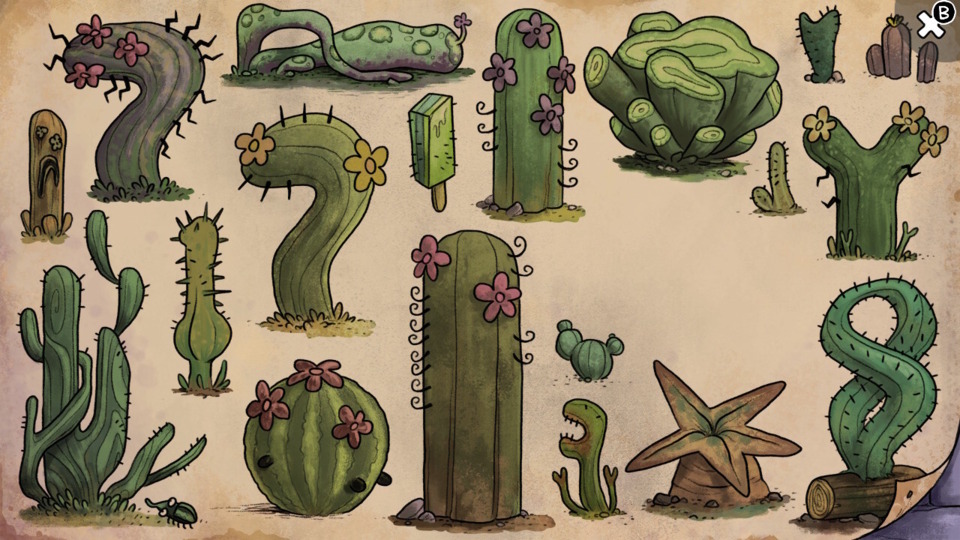

On the whole, the puzzles in this one are slightly tougher than the previous game's, but the aforementioned compartmentalizing of the game's regions means you're unlikely to be stuck for long. However, there are a few where you might need some external note-taking to solve them, including a puzzle where you have to instruct someone to draw a specific unseen breed of cactus by comparing and contrasting with six others: the idea being that three of these cacti have characteristics that the final one might have, but are not apparent on the other three, which means eliminating every element that appears on those latter three (it makes slightly more sense in-game). There's another puzzle involving connecting nodes on a switchboard that relies on some entirely unhelpful new age-sounding hints about the sun and roots and whatnot: these hints actually correspond to icons on the switchboard, but the symbols and the instructions are often so vague that you're left trying a bunch of combinations for many minutes until everything finally lights up.

The script is generally witty and like the first game leans into Robert's oblivious wishy-washy nature and Laura's aggressiveness to humorous effect, giving them a lot of material to work with when talking to each other or NPCs. One particularly mean-spirited running gag carried over from the first game is the way that some adventure game puzzles call for the occasional bit of misanthropy, and the soft-hearted Robert always chastises himself for possibly hurting or killing an unhelpful NPC once you've solved whatever puzzle is connected to them - small splashes of dark humor like this are common to the Simon the Sorcerer template these games venerate. NPCs can be interrogated on a number of topics, each of which are grayed out on the interface when no new information can be gleaned, though those same options won't disappear entirely if you need to hear them again for the sake of a hint. Speaking of which, the in-game hint system seems to have been altered too, and now they simply remind you of what your current goals are; find a way to get this item, distract this NPC, and so on. Handy for a refresher if you're completely lost, but you're not going to be able to rely on them for explicit instructions.

The Inner World: The Last Wind Monk carries over the strengths of its predecessor even if it hasn't evolved too much - that's perhaps by design, given that it's from a throwback genre - and after two games it's evident that Studio Fizbin has a very clear idea how these games work and what makes them appealing. My usual favorite QoL features are here, specifically the button that highlights all hotspots on the screen to eliminate pixel hunting, and visually the game has a simple look that nonetheless benefits the light-hearted adventure it presents. That it can also juggle darker themes like child abuse (verbal and physical), religious persecution, racial discrimination, and oppressive autocracies while maintaining its sense of levity is admirable also. The one negative I can hold against the game beyond a few duff puzzles are the awkward controls on Switch if you're playing that version while docked: instead of using the analog stick as a cursor, you have to walk as close to the desired hotspot as you can and hit Y enough times to cycle through all the nearest hotspots until you get the one you want. It's awkward enough, especially when there's a group of hotspots bunched up together, that you're far better off playing undocked and using the touchscreen for everything.

Ranking: C. (I've been packing the C-tier with so many new additions since embarking on this blog feature that I've lost sight of where the current goalposts are, but I'm pretty sure The Inner World: The Last Wind Monk will make it in. It's a solidly made throwback with a few fun gags and a slightly higher than average challenge level but isn't particularly remarkable or noteworthy beyond that, which is why it won't be placing higher. For reference's sake, the B-tier has games like Gorogoa, Life is Strange: Before the Storm, What Remains of Edith Finch, and Rakuen - all very daring games both thematically and mechanically. C-tier meanwhile has Tacoma, Night in the Woods, Subsurface Circular, and Bear With Me which are better neighbors for The Last Wind Monk's modest charms. Damning with faint praise perhaps, but it really is getting competitive in that region of the list.)

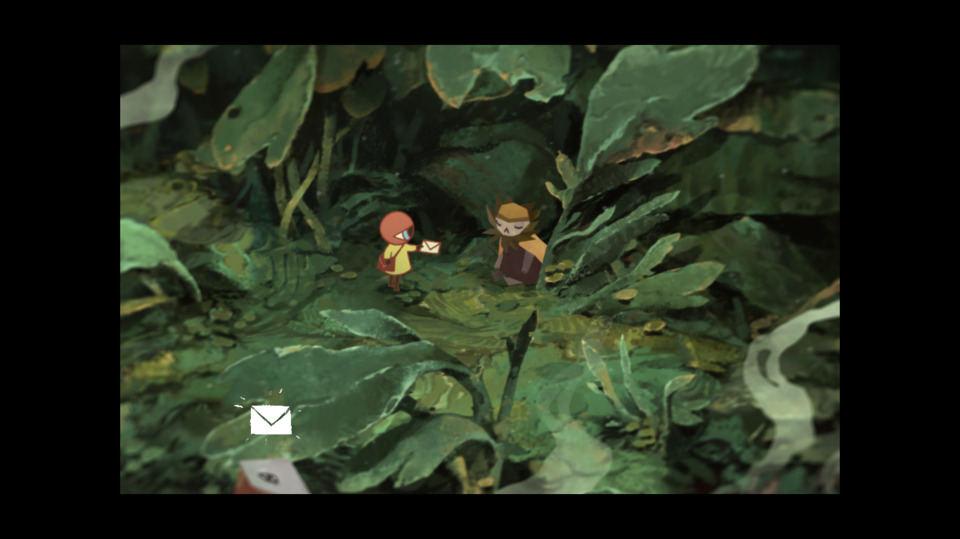

Tiny Echo

Even compared to the breeziness of the above game, Tiny Echo is considerably more modest and streamlined. Centered around a simple quest of delivering thirteen pieces of mail to enigmatic beings across a subterranean world, Tiny Echo is far more dreamlike and sensory in its approach and like many foreign-produced adventure games (the studio, Might and Delight, is based in Sweden and is best known for those Shelter arboreal survival games) foregoes language and text for mostly ideographic and contextual exchanges. The protagonist, a little eyeball with a torso and legs named Emi, sets out to deliver what aren't so much physical envelopes but manifested wishes: these all come from the surface, where a group of odd humanoids are struggling to survive a barren world. By awakening the spirits these wishes are for, each representing a different natural or manmade concept, the surface becomes that much more survivable for its occupants.

Because emotions and immersion play a larger factor in its wisp of a narrative, the game is a sensory treat: visually impressive with realistic looking areas (they almost look like miniatures) with less-than-realistic anthropomorphic residents, and great sound design that often are a factor with the game's puzzles along with a serene soundtrack that is like a balm for the soul. It's very akin to the work put out by Amanita Design: playful experiences connected by a loose thread of a narrative rather than something more story- and script-focused. While the world is relatively small it compensates by being a little convoluted in its structure, with doorways often leading to unexpected exits. You'll often solve a puzzle or activate an object in one area for it to open a route somewhere else, so you get to learn how the game map operates with some exploration and experimentation. An early example involves waking up a creature sitting in a hole: once awoken, the creature sits up and reveals that its lower half was blocking a tunnel. That same creature is one of the thirteen that you must deliver a message to: some are ready to accept your delivery as soon as you find them, while others might involve a little mini-game or puzzle before they're amenable to receiving their mail. The latter scenario constitutes the majority of the game's interactive aspect, which is otherwise fairly slim and lacks mechanics common to other adventure games such as a persistent inventory or a means to communicate with NPCs that isn't just handing them a letter.

Tiny Echo is a brief (about ninety minutes) and simple yet attractive and thoughtful adventure game that fits the Indie model to a T: it's not something you could hope to sell in a retail context, so minimalist is its approach, but something worth seeing through for the meagre amount it asks for to enjoy its surreal, striking aesthetic and smattering of cute environmental puzzles. If you're a fan of artsy point-and-click games from Amanita or, going further back, Windosill or The Tiny Bang Story, it's worth seeking out.

Ranking: C. (I'm starting to realize my lazy tendency to give everything four stars is going to bite me in the ass in this case, since I've taken an already competitive tier that was twenty games strong and expanded it to at least fifty since January. I've no idea where Tiny Echo will end up on the finished list, but I feel its combination of strengths and weaknesses - though different to The Last Wind Monk - will put it in a similar position. Its dreamlike ephemerality, though potent while in the moment, might end up working against it come the final judgement.)

Chaos;Child

Chaos;Child follows last month's The Letter as a visual novel that I was able to talk about in two separate features (the other being VN-ese Waltz, my unfortunately-named trek through some big name visual novels) and like The Letter is a spooky supernatural thriller where anyone might perish at any moment. I've discussed most of the essential qualities of Chaos;Child in its aforementioned VN-ese Waltz entry, so this will be a round-up of final impressions and spoiler-blocked plot twist discussions. (Just for a recap though: Chaos;Child is set in Shibuya some six years after a massive earthquake leveled the area. Recently, a string of bizarre murders has caught the attention of the local highschool's newspaper club, the president of which finds himself entangled with the murders and, soon enough, a far more dangerous and strange reality hidden beneath Shibuya's surface.)

Chaos;Child was considerably darker than I anticipated, even with those grisly and bizarre murders right at the forefront. The default story becomes almost a struggle in part because of the procession of downer moments that punctuate the late-game, or at least its default route. Speaking of which, the game has an uncommon structure when it comes to replays for alternative endings. I figured the delusion feature of the game - where the protagonist imagines a positive or negative fantasy scenario, or skips them both to stay on track - would have some effect on story branches, and I was right to an extent. What actually occurs is that the delusions have zero effect on your first run through the game: the story is railroaded to a specific conclusion regardless of any delusions you may or may not have triggered. Upon a new game, though, you have the opportunity to unlock character-specific routes regarding four secondary female characters based on activating specific delusions related to them: the protagonist's overbearing older foster sister Nono Kurusu, the bubbly underclassman and human lie detector Hinae Arimura, the quiet gaming otaku Hana Kazuki, and the legally dubious foundling Uki Yamazoe. Not only do each of these smaller scenarios explore what might happen if you get closer to that character - mild spoilers, but none of these "romances" end well - but they also reveal important character motivations and other vital background information about the overarching story that help fill in gaps in your knowledge. It's only once you've seen all four of these routes and learned all they have to impart that the "true" ending, set a few months after the main story, can be viewed. The true ending works better as a satisfying conclusion to the story as you might expect, though there's still much heartbreak in store and the door left wide open for another story set in the same world - something that the Science Adventure series as a whole excels at, given its many sequels.

Anyway, I'm glad Chaos;Child didn't descend into a thousand-branch nightmare like The Letter - as clever and difficult as wrangling that many variables must've been - and playing through the game the first time while cherry-picking delusions (or save-loading before the delusion trigger to see both) made it easier to ascertain which ones would trigger specific character routes, so it's not quite as obtuse as similar VNs have been. I still dig a big ol' flowchart of decision branches I can navigate, such as the one in Zero Escape: Zero Time Dilemma, but Chaos;Child's approach works as a more subtle alternative.

So, as is usually customary in VN-ese Waltz when I can actually complete the game in time, I've got some spoiler-blocked sections that discuss the end-game. I've separated them into three categories: the end of the normal route, the content of the four character-specific routes, and then a smaller blurb on the game's true route and finale. The idea is to peruse them once you've passed those parts of the game, though if you're not interested in doing that and just want to hear about some wild anime shit by all means partake at your leisure.

Part 1 (Normal Ending):

Part 2 (Character-specific Endings):

Part 3 (True Ending):

Anyway, I think the mark of a good visual novel - or a regular novel for that matter - is that it leaves a strong enough impression for this amount of garrulous musing on plot details days later. Those murder scenes aren't something I'll soon forget either.

Ranking: B. (Steins;Gate is one of the strongest VNs I've encountered while covering the things and Chaos;Child is only slightly worse in my estimations, making it a strong contender for the top half of the list at the very least. I'm putting it in the B-tier just so I don't triple up on the poor old C-tier for November's entry, but it might end up slipping to just under 40th place when the dust has settled all the same. Again, given how I've turned this list into an organizational bloodbath to contend with in a few more weeks after this series reaches its finale, it's certainly not a placement to sneeze at.)

Next time: There was another Falcom RPG released in 2017 so you best believe it's going to be my swansong for this feature. It'll be a busy month with the holidays and this ridiculous GOTY-related feature I'm batting around so I might not have time for anything more, but I'll see what I can scrounge up for some last-minute additions. We've now reached 107 items on the list - 101 if you remove the HOPAs and the one F-tier I've awarded - which means we're safely in the clear regardless of what December brings. That's a(n entirely self-inflicted) load off, at least.