Rami Ismail is one half of the team best known as Vlambeer, the developer behind games like Ridiculous Fishing, Luftrausers, and Nuclear Throne. Getting him to stay in one location long enough to have a conversation may prove difficult, so try talking to him on Twitter instead.

2017 was an extraordinary year for me in many ways, most of which not related to game development. While Vlambeer is stirring again after a long hiatus, this year focused on both of recovering and healing from running a tiny, lovely, stressful indie studio for seven years already. Where my co-founder decided to work on Minit with friends and his partner, I decided to spend a year focus purely on everything outside of making games.

That means I toured the world a little less this year, spending only 200 days abroad, and finally got my drivers’ license, introduced my mother to gaming via Final Fantasy XV and Dragon Age: Inquisition, and got married to my wife, Adriel, during a perfect ceremony surrounded by amazing people on the beautiful island of Malta. I spent the other days of the year reading a lot of books, watching a lot of movies, and--obviously--playing a lot of games.

And gosh, was there a lot to play. Early 2017 felt like an unexpected extension of the overwhelmingly amazing release rush at the end of last year, followed by a highlight in the hype-surrounded release of the Nintendo Switch. As I write this, I could literally not imagine traveling without my Switch, and I genuinely have turned into both one of those people that asks "what about a release on this other platform," and a walking Nintendo advertisement.

One of the more exciting moments of this year happened midway throughout the year, as the re-appearance of the mid-budget title was one of the least-contested experiments in AAA studios surviving the weird stalemate they’ve reached balancing budget and expectation.

In independent games, as most notable indie games’ budgets rise above the hundreds of thousands of dollars, gaining access to a ‘cut of the pie’ has become a target most new developers (wisely) avoid, instead opting to create in an entire new layer of experimental games. That layer will slowly grow into a full form, just like indie originally grew under the "budget AAA" genre. It’s a rough new space, but it feels teeming with potential, and I’m incredibly excited to see what gets made there over the next few years.

Like last year, I have one caveat before I start: I think the core design of PlayerUnknown's Battlegrounds is phenomenal, but I don’t enjoy playing it as much as I enjoy appreciating it. You won’t find it on my list, although I want to acknowledge the effect it has had on gaming all-year round. We have our new Minecraft, and I can’t wait to look at all the also-PUBG’s that’ll come out the next few years in a weird mix of amusement and desperation.

Best Game: NieR:Automata (PS4, PC)

My top 5 games list has been the same for over a decade, and NieR:Automata is the first time it has changed in a long time. NieR:Automata is the weird fusion of a game designer with a remarkable understanding of our medium, and a studio that can make a great Transformers game. What makes NieR:Automata stand out is that it shouldn’t work, and it often stumbles with things that feel like amateur errors, but somehow, it all adds up to be by far the single-most compelling game in years.

The first play-through of NieR feels remarkably sloppy, with a poor sense of progression and direction, multiple quests that feel broken or out-of-place, and a story that feels like it could’ve been that much more. The second play-through of NieR is the same story from a different characters’ perspective, and it feels revolutionary, and you have a sense of progression because you already know where it ends, and those broken quests and plotlines suddenly make sense, and the story fleshes itself out to be so much more. By the time the third play-through is well-underway, NieR has become unforgettable, the stakes have become unforgettable, the story crescendos into the unforgettable, and the conclusion is unforgettable. NieR would already be my Game of the Year if it stopped there, but the credits sequence and questions posed therein make it unquestionably one of the greatest games ever made.

Favorite touch: There is a moment in NieR:Automata that reveals just how well the game revels in using the players’ knowledge of games to emotionally prime or manipulate them. Halfway through the final play-through, the doors on an ally close in her self-sacrifice, NieR’s phenomenal soundtrack swells, and the game cuts to black. The words “Developed by PlatinumGames” fade into the screen as if it’s the opening of the game. The sequence continues as if the game is just opening, with opening credits and title-cards mixing with the on-going cutscene, despite the player having spent 30+ hours to reach that point. The game uses the players’ understanding of game frameworks as a way to indicate that a new world has begun, and primes us for a new beginning, and we should not expect the old status quo to return. It’s simple, and I still get goosebumps thinking of just how effective that trick was.

Least favourite thing: NieR is broken in an infinite amount of ways, and it’s hard to argue the first-run progression is anywhere near what it should be to be an alluring kind of game. The amount of friends I’ve recommended this game to that understandably bounced off of the first play through remains one of the saddest truths of any game recommendation I’ve ever made.

Alternatively: Mario Odyssey is a masterclass in game design. From the laser-sharp focus on Cappy, to the level design that expertly allows players to approach things from multiple player archetypes and playstyles, the game offers dozens of hours of gameplay almost completely devoid of any significant flaws.

Best AAA Game: Persona 5

If 2016 was a return to form for first-person shooters, 2017 was a return to form for Japanese video games. While the AAA output from Japan hadn’t been abysmal, it definitely went through a lull and got left behind a bit as the Western industry kept evolving. 2017 showed that Japanese can evolve just as well, and Persona 5--the latest instalment in the equally beloved and adored as opaque and inaccessible Persona series--shows how to leap forward.

With a incredible cold open, the game kicks off in high gear with an introduction that cleverly allows the game to foreshadow events ahead, and guide the player through their first adventure in its world. The game meanders between the brilliantly designed JRPG action-packed in gorgeously hand-designed palaces and the purposefully slow grind of daily school life, always nudging you to divide your attention between both, but rarely ever forcing you one way or another.

The thing that really stands out is the interface: I cannot remember the last time any RPG had an interface that felt this snappy and aggressive. Most turn-based combat systems feel strategic and intricate, but Persona 5 revels in its characters’ rebellion and their destructive powers towards the enemy combatants. There is a directness and boldness to the interface and animated battle sequences are a huge part of establishing that feeling.

Persona builds an intriguing cast and world, and manages to dangle just enough carrots in front of the player to keep you guessing for what comes next, while giving you enough hints to keep you trying to upcoming certain plot points. While the game stumbles a few times in its final act, the final showdown and resolution are both more than worth fighting through.

Everything in Persona 5 feels smooth and rebellious, and the Persona staple ‘One More’ system that allows a player to string together multiple attacks if they exploit an enemies’ weakness is no exception. In Persona 5, the Baton Pass adds to the system by allowing a character to pass on their turn to another available character of choice, so that they can continue their streak with a small boost. It’s simple, but it allows for so much more clever-feeling freedom in combat. This game even rebels against its own character attack order.

Between an incredibly bold style filled with bright saturated reds, blacks, whites, diagonal lines, striking shapes and illustrations, and an effortlessly memorable jazz-y soundtrack, Persona oozes its main theme, rebellion. It’s rare that every part of a single game feels geared towards a single word, but Persona 5 manages it while still being too cool to break a sweat.

Most favourite touch: The structure of the game’s story is remarkable. I’ve played many in-media-res and convenient-amnesia type of stories in games, but none use the central hinging moment as beautifully as Persona 5. The opening of Persona 5 occurs near that moment, as the protagonist gets arrested and interrogated by Sae Niijima, a special prosecutor. Using Sae’s forward interrogation dialogue, the game can set up antagonists and events far before they happen by having her mention them, and each chapter begins with Sae discussing the protagonists’ crimes. You spend the entire game trying to get ahead of Sae, figuring out what led to your imprisonment. It only makes sense, then, that the central hinging moment of the narrative shows that things aren’t quite what they seem.

Least favourite thing: Persona 5 opens in a brilliant casino-sequence of high-paced stylish action to introduce its combat, and then cuts to a dreary Tokyo district for the introduction of the social element of the game. It would work if Persona didn’t insist on the first hour or so of the social element entirely linear, and if the linearity wasn’t underlined by clearly locking a lot of options behind a “You must be tired after today. Let’s go to sleep.” dialogue prompt. By the time the game opens up, I’d been primed to hate those two sentences enough that every time something triggered them later on in the game, I’d instantly feel as dreary as those Tokyo skies.

Alternatively: OK, listen, I know being Egyptian might have introduced some bias here, but I can reassure you that the margin by which Assassins Creed Origins stood out to me will minimize the effect of that bias. For the first time since Brotherhood do I feel fully engaged by an Assassin’s Creed game, and maybe that is because the series finally dared to re-invent itself. While some might argue Origins is a good game but a bad Assassins Creed game, I say good on Ubisoft for daring to do something new with their franchise.

Best AA-Game: Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice

Hellblade feels special because it breaks through two important barriers at once: making a genuine game about mental disorder, and making a AAA-feeling independent game. In an industry in which AAA is increasingly trying to find new ways to get money out of people to fund the blockbusters of tomorrow, Ninja Theory tried the opposite: what if they made a game that’s smaller and cheaper--and since the risks are lower--do something a bit riskier?

The result is Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, a game that is distressing and violent and scary and informative. The game is effectively a thriller-meets-walking simulator, mixed with a simple "hidden object" game, mixed with a satisfying Bloodborne-lite combat game. You take control of Senua, who experiences psychoses, but is mostly defined by her aim to resurrect a loved one through a vision quest through Celtic and Nordic mythology. Throughout the game, Senua faces mythological creatures and deities, each tied to their own gameplay mechanic, but without really building forward on those mechanics. They appear, you master them, and the game moves on. It feels different, but it’s not jarring.

A lot of the game was designed with feedback from people that experience psychosis, and while the game will never fully be able to articulate every experience with a topic as personal and diverse as mental disorder, it manages to feel genuine and sincere. The game doesn’t hold any punches, and if you’re anything like myself, you’ll need to come to terms with how Senua’s mind works as you play to resist the urge to quit and escape the continuous horrors she experiences--a luxury that the main character doesn’t have.

A large part of that is in the audio, which the game recommends you experience through binaural 3D headphones. The voices that Senua hears move towards and away, taunt and advice, whisper and scream. They’re continuously there, and the game uses them to phenomenal effect, making you hate them when they’re there, but making you miss them when they’re gone.

Senua crafts a compelling story, a strong and phenomenally acted hero, in a fascinatingly harrowing but beautiful world. More than anything, the game gave me a small glimpse--even if just a voluntary, temporary glimpse--of a human experience I would’ve never been able to feel otherwise. Nothing but a game would’ve sufficed to communicate this experience, and Senua’s Sacrifice manages to use small scope and budget to impress way beyond its resources.

Most favorite touch: I couldn’t pick here, so I’m picking two: the developers’ bluff at pretending there’s a perma-death system in the game to raise the sense of tension is daring, bold, and a strong reminder that games are less about what they are and more about what the player believes they are. The other thing is far more subtle--during combat, I love the way the camera snaps between enemies when switching targets, and the slow movement the enemies have towards you make switching between two targets marching at you frequently a proper strategy. The camera snapping feels urgent, hurried, and panicked, and it made me love the combat so much more.

Least favorite: Senua’s hidden-object moments are often far from strong, and feel somewhat out of place. While there are genuine moments of brilliance even in the shape-matching mini-game, more often than not I found myself running around waiting for the screen to light up before swerving the camera around wildly--not something that fits Senua, her character, her circumstances, or the world around her.

Best Atmosphere: Yakuza 0

Ah whatever, I’m doing it: Yakuza 0 was the most atmospheric game of 2017. Yes, I know it doesn’t have dreary violins, and there’s no beautiful piano solo, and no glowing orbs that remind us of our humanity, but holy shit, have you ever seen a young Kazuma Kiryu pick up a phone? If that doesn’t remind you of what truly matters in life, I don’t know what will.

Yakuza 0 is an action-adventure brawler that manages to walk the thinnest possible line between absolutely preposterous, weirdly offensive, breathtakingly hilarious, depressingly nihilistic, and straight-faced crime drama. The story starts with shit hitting the fan as your protagonist is framed for murder, and as the game goes the amount of shit increases exponentially until by the end of the game the situation has escalated to a planet-sized shit hurricane as you’re at the centre of a nation-wide yakuza conspiracy claiming dozens of lives, fighting over succession rights for the clan, the future of a city, billions of dollars in cash, and the lives of those both innocent and dear to you. That is, you’ll get back to that after you stop tweaking your micro car because you need to beat an 11-year-old at model car racing, and maybe there’s some time to help this super-popular band of Elvis-wannabe figures out with pretending to be cool by advising them on how to be as yankee as possible during a surprise Q&A with their fans.

But when Yakuza 0 wants to play straight-faced crime drama, it doesn’t miss a beat. Kiryu is thoughtlessly empathetic, often landing himself in ridiculous situations, while his counterpart and the second playable character Majima is always a bit too empathic for his own good. Throughout the game, the game switches perspectives like a television series, complete with last time on this story intros, and always at exactly the moment you really want to know what happens next. By the time you realize you care for the characters, the game has already set them up for a perpetual fall from grace, every solution to every problem causing bigger problems with allies or enemies unknown or unforeseen.

Throughout all of it, Yakuza 0 feels right. The city, the people, the seriousness and silliness, it plays off of each other seemingly effortlessly. I never doubted its atmosphere for a moment, whether it was singing “Judgement” at a local karaoke bar, blocking a metal bar swung at my from a motorbike racing at me in a sewer pipe, or watching a tense interrogation scene play out resulting in the loss of a formidable ally.

Favourite touch: If you hit an enemy, which happens frequently as somehow every street corner of Tokyo and Osaka has thugs waiting to be spectacularly disposed of by you, stacks of money literally fall out of them, because why not. It’s a weirdly satisfying alternative to the usual blood flying around, although Yakuza 0 doesn’t shy away from buckets of blood either. I guess someone on the development team just thought hundreds of bills flying out of somebody’s face to flutter around a fight would look cool, and they were so right.

Least favourite thing: Every single stealth section in the entire game. It’s very hard to justify the clunky mechanics of awkwardly sneaking around a bunch of enemy combatants because of "danger" when the very next scene involves Kiryu confidently and effortlessly disposing of a good thirty unfortunate and heavily armed opponents.

Alternatively: The way What Remains of Edith Finch structures its characters, worlds, revelations, and story is poignant and powerful, and its clever use of vignettes to communicate all of the above is incredibly evocative.

Best Emergent Territory: Engare

Mahdi Bahrami’s previous title, Farsh, is a title that I often use as example when discussing how supporting more diverse game developers can lead to entirely new mechanics, aesthetics, mythologies, and stories being introduced into our medium. A game focused around rolling a carpet, the game is rooted deeply in Mahdi’s Iranian background, but Mahdi never tried to make a game about Iran. He just made a game, and him being from Iran made the game Iranian.

His latest game, Engare, is a near-flawless execution of exactly that same notion. A challenging puzzle-game, the game is rooted in Islamic geometric art, and at its most simple asks the player to place a single dot on a contraption. Said contraption will then move according to the laws of the game, and the dot moves along with the contraption, drawing a line on whatever it touches. If your dot draws the shape you’re challenged to recreate, you pass the level.

It’s infinitely mesmerising, and frequently challenging as the game offers more complex situations, contraptions, and challenges. For those people who just like pretty shapes, the game features a sandbox mode where you can experiment with contraptions and results. Half game, half toy, Engare is a stark reminder that there is so much more game out there, waiting to be made, if the industry supports creators from other places in achieving their dreams of making games, too.

Favourite touch: If you pass the level, the contraption continues moving, revealing complex geometric art, colours, and shapes. It shows that repetition and pattern can create beauty, and beating a level ends up becoming its own reward.

Least favorite: At times, Engare feels like it never quite figured out whether it wanted to be a sandbox or a puzzle game, and some of the puzzle levels feel less like they have a solution and more like they’re an excuse to try all sorts of random things. It’s not a terrible problem, but it sometimes makes finding the actual solution feel less rewarding, instead of a gained understanding.

Best Whimsical: Fidel Dungeon Rescue

Dungeon crawlers, roguelikes, and roguelites come in incredible variety, from Vlambeers’ own over-the-top-down-shooter Nuclear Throne to Michael Brough’s incredible Zaga-33, and from Spelunky to Crypt of the NecroDancer. One entry that came out earlier this year was Fidel Dungeon Rescue, and it’s probably one of the cleverest implementations of the genre I’ve seen.

It’s a one-screen dungeon crawler where the challenge isn’t uncovering the route, but finding the best route through what is presented. It’s a game with an undo functionality, it’s a game where death is not necessarily the end, it’s a game in which you play a dog and you can bark.

If that makes Fidel Dungeon Rescue sound easy though, it’s anything but. It’s accessible--as in most people would be able to pick it up and play--but it’ll often leave you staring at a single screen in disbelief, as you poke and poke at solutions that never quite work out. It can’t be that hard to solve this, you think to yourself, until you realize that master-designer Daniel Benmergui has crafted something deceitfully clever, and you either yield or the ghost chases your run to an ignoble end. As your dog's ghost flies to the heavens, the game will remind you that the SHIFT button barks, and then taunts you that dead dogs can’t bark if you try. Don’t be fooled by the cute aesthetic or the accessibility features, because Fidel Dungeon Rescue will tear everyone down equally and it will clearly enjoy it.

Fidel Dungeon Rescue feels like your favourite Picross-like game mixed with the depth and layers of your favorite roguelike. It’s bite-sized but worth really committing to. You’ll find new mechanics and secrets and enemies and obstacles frequently, you’ll run into unsolvable walls only to realize you should’ve made a better choice minutes earlier, and you’ll bark your way to the very end, because darn it I’m smart enough to solve this thing, Daniel, you won’t get to taunt me that I can’t bark as a dead dog again, just you wait.

Favourite touch: Fidel Dungeon Rescue’s undo is not unique, but it’s brilliantly applied here. To undo any move, you simply move backwards over your leash. It’s simple and effective, and a great application of don’t introduce a new button unless you have to.

Least favourite: The ghost in Fidel Dungeon Rescue is the only way you can lose the game, but it feels a little haphazard. It does a good job of building tension and allowing a tight escape, but more often than not you find yourself staring at the screen for three seconds, wishing the ghost wouldn’t waste your time rushing at you with no way to avoid it.

Alternatively: Everything. I don’t understand why it is enthralling, but it is. I don’t understand why I keep playing for a little bit, but I do. Everything is a toy masquerading as a game, a game that is acting as if it were a statement, a statement that pretending to be a toy. There’s a joy to it that is different from other games, and there’s a curiosity embodied in the game that--if you let it--can be a great conversation partner for conversations about nothing and everything.

Best Multiplayer: Destiny 2

Destiny 2 is the thing I love about second installments of games: they’re that iteration that a first game could never make because of choices made early on that turned out to hinder more than help later on during development. On the other hand, they’re not a third game--the game that gets made because now a franchise is a genuine franchise, with all the additional risk aversion that comes with that. Mass Effect, Assassins Creed, Half Life, Uncharted--the greatest video AAA game series are often at their strongest in the second game, and it is with that in mind that I understand Valve’s decision to never release Half Life 3.

Going back and playing through Destiny’s full story clearly shows Bungie’s understanding of the behemoth they’ve created improving, and you can see how they started to define the shapes of Destiny 2. Events in patrol spaces that would eventually become the High Value Targets, multi-step patrols that would become the Adventures, increasingly complex and cinematic story sequences and characters that would become the heart of the Red War campaign, and ever-more vertical spaces in the Taken King as the development team first removed the shackles of the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3, and then the shackles of the original game engine. The Crucible’s remake is never clearer than in the incredibly streamlined Control mode, which allows for more tactical and interesting play with the smaller teams and tighter maps--offset by the faster captures. Destiny 2 feels like Bungie has figured out how to build a foundation to expand upon, instead of the first games’ precariously towering improvements expansions, and it feels incredibly coherent.

Even considered without its prequel, which will forever be etched in my heart as the game I got proposed to in, Destiny 2 stands incredibly strong. The game’s Milestone system has players returning weekly if they want, the updates and expansions come out at a steady enough pace to leave and come back again, there’s enough content in Lost Sectors and Nightfalls and Crucible if you choose to, there are enough weapons and armour to find if you care, enough light to upgrade towards if you can be bothered, but nothing feels forced and the game never asks for too much.

There’s always something to do, but never too much to do. It’s a subtle balancing act to prove a whole experience for those who play hours daily, and those play an hour weekly, and Bungie and their team managed to walk that line admirably.

Favourite touch: The new ability paths feel like a significant downgrade to Destiny 1 at first, as they allow far less customization. It took me some puzzling to figure out what the advantage here would be, but as I played I realized that the limited player paths allow Bungie for extreme freedom in creating their weapon and armour perks. Combined with the overhauled weapon classifications, which see players switching around load-outs more frequently, Destiny 2 actually gives players far more freedom to express themselves, and nudges all players to tinker with their character setup far more than the static ability selection screen from the first game. It’s another example of the subtle brilliance at play in the design, and another reason to appreciate Bungie’s willingness to rebel against what is expected to create something new that’s good.

Least favorite: I understand why the token system exists, but I truly, deeply, dearly miss the end-of-mission rewards that made the end of any activity such a rush. Destiny 2 feels more check-the-boxes than Destiny 1, and while that’s not necessarily a bad thing, finding a Gjallarhorn at the end of an intense session of gameplay felt better than finding a Prometheus Lens at a random vendor in exchange for tokens.

Alternative: The Nintendo Switch feels made for multiplayer games, and even though Mario Kart 8 and ARMS and Splatoon 2 are all phenomenal multiplayer games, the multiplayer game that really stood out this year was Snipperclips: Cut It Out, Together! A simple mechanic with deviously clever challenges make the game into a memorable experience, best shared on the small screen.

Best B-Game: Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy

Bennett Foddy’s Getting Over It is an homage to an indie game from a different age, when the most famous independent developers mostly knew of each other, and most of the indie scene made strange, experimental B-games mostly because they could. Some of those games were good, most of them were bad, some of them spoke to something fascinating, and many are games that are offensive or otherwise immature. To me, as someone who lived those years in an early part of my career, it is a nostalgic feeling, not one of wanting to return to simpler days, mostly because the things that are happening nowadays are infinitely more exciting.

But some of the games made then were the spark and the inspirations of the developers that work today, and one of the games that was fascinating was a game by a developer by the name of Jazzuo. Jazzuo’s Sexy Hiking was a compromise-less game about manipulating a hammer as your sole mode of movement to hike through a complex environment.

One of the games industry’s less obscure historians is Bennett Foddy, a professor at the NYU Game Centre and an independent game developer himself. His games include some of the most frustrating, broken, and frankly unplayable games that have ever gained widespread renown: QWOP, a game about running down a 100 meter track by controlling the thighs and calves of a character; GIRP, a game about climbing a small wall by using every letter key on the keyboard; and CLOP, a game in which you control a horse trying to cross a small hill.

Getting Over It combines Bennett’s understanding of games, controls, and history seamlessly. The game plays pretty much like you’d expect--and the homage to Sexy Hiking makes it feel like Bennett’s output was deeply inspired by it: the game offers a very simple task, an extremely convoluted control method, and a million ways to make mistakes that’ll cost you only minutes of progress if you’re lucky, and way more of it if you’re not lucky.

While you’re playing, Bennett Foddy speaks to you from the game as a caring parent watching their child, explaining the history of the game and its inspirations, the way he approached creating the game. More importantly, this narration explains his thoughts on what the game is and represents, and his thoughts of what a game is and represents, and his thoughts on what games are and represent.

Bennett describes, in no uncertain terms, one of the stranger tensions of game development: we have to love our work and the player equally, but to make them mesh, we often have to hurt both. Getting Over It, as a game, is about hurt, love, challenge, pride, hubris, joy, guidance, independence, unfiltered rage, determination, despair, regret, victory, and loss. A game with such lofty ambitions cannot exist without asking a lot of the player, and it asks for your undivided attention both emotionally, physically, and intellectually.

Favorite touch: Bennett’s genuine concern for the player, something you can clearly hear in the love for the player in his voice, as his work mercilessly taunts you. It might feel like a strange juxtaposition, but let me reassure you: Bennett made this because he wanted to, and he sincerely and deeply cares for every player that touches it.

Least favourite: I have nothing. This game is pure.

Alternatively: Freeways is a game about drawing a highway system. It’s interesting, simple, and fun, and a worthy way of spending an hour or so. You might find yourself sucked into the game, and at that point, there’s no knowing how much time you can spend on making something just a tiny bit more efficient than your previous attempt.

Best Indie: Gorogoa

It’s rare that a game can make you feel clever without feeling condescending, and Gorogoa manages to walk an impossible line between being an incredibly clever game, and an incredibly rewarding playground. With a relentless internal consistency, Gorogoa is a puzzle game based around manipulating four panels, panels that can be interacted with independently as well.

While that might sound abstract, in practice it feels extremely natural. Explaining more of what the game is would be a disservice to it, as so much of the reward of playing Gorogoa is in the sudden realizations, the unexpected surprises, and the joy of figuring out a new way to manipulate the panels and their contents. The game isn’t trying to make you feel clever by telling you you are, or by creating reward structures, or by creating clearly defined sequences with an ending--the game makes you feel clever because you can keep up with how clever it is.

Gorogoa is one continuous puzzle that tells the story of a boy trying to avert a terrifying future, probably, because while the story plays out throughout the panels as you solve the puzzles, it is also presented in a way that leaves a lot of room for personal interpretation. Usually, solving a major puzzle leaves you with one animated panel in which the boy achieves the goal of the puzzle, and that panel’s animation ends with the start of the next puzzle.

The game feels like the first video-game equivalent of Alfonso Cuarón’s incredible long take near the end of Children of Men, a new type of expression of mastery, a dedication to craft, and an unwavering attention to detail. In one fluent hour-long sequence, the game introduces itself, all of its mechanics, its levels, the easiest and most complex challenges, protagonists and antagonists, the premise, the story, and the resolution.

Favorite touch: Gorogoa feels precise. There is not a single moment that is superfluous, and not a single moment is missing. It has a level of intent and a clarity of design that is unrivaled. Regardless, the game is an absolute joy to play, and giving away my favourite touch in this game would be incredibly unfair to everyone who hasn’t had the opportunity to do so themselves.

Least favourite: I have nothing.

Alternatively: SteamWorld Dig 2 evokes the brilliant Spelunky, but is an entirely different beast. Masterfully designed environments full of secrets and puzzle-like challenges, SteamWorld Dig 2 was my ambient game for weeks, the game I would mindlessly enjoy when I needed distraction, and fully engage with when I wanted to make progress.

Best Mobile: Bury Me, My Love

One of the reasons I enjoy this medium is because it can place you in situations you would never find yourself in, like being a super soldier fighting a intergalactic war, or a expert race driver, or a cunning thief unraveling a global controversy. Another one of the reasons I adore this medium is that it can place us in situations that we could find ourselves in, but without the real-life consequences.

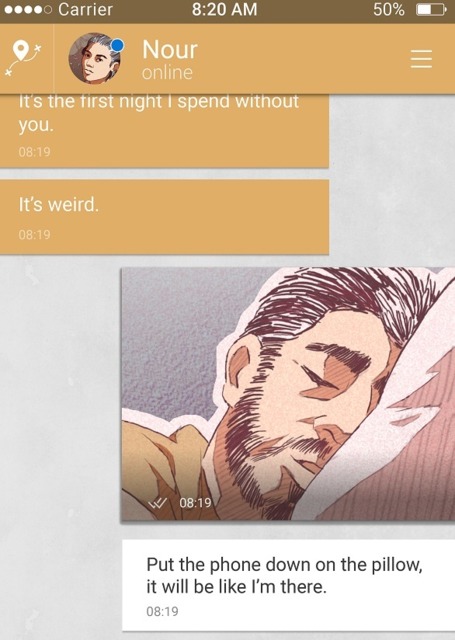

Bury Me, My Love is a game about two people in a situation that 5 million people on this planet have lived or are currently living. You take the role of Majd, a Syrian citizen living in the war-torn country taking care of his elderly family. Your wife, Nour, undertakes the dangerous journey to escape from the country, and you two stay in touch via phone chat.

The game uses the phone as its literal interface, pretending to be a chat app. You pick conversation choices to give advice, encourage, warn, and entertain Nour as she travels, and then you wait. Nour sometimes disappears for hours, and there is nothing you can do but wait as you hope that she is finding a place to charge her battery, but you know she might have been captured, arrested, or killed. At no point does stray from being that, a communication between people, and at no point does the game tell you how to feel or what to think. It is genuine, restrained, and deeply powerful.

The game is directly inspired and based upon the stories of many refugees that have made and survived the trek to safety, and paints an incredibly human story filled with choices that have no right answer. The tensions and situations that occur are human, strains on relationships, trust issues, and people making choices for themselves.

As a half-Egyptian, I find “Bury Me” to be one of the prettiest Arabic words, يقبرني. The phrase loosely translates to “I hope you will eventually get to bury me, so that I don’t have to suffer the pain of burying you”, and is a commonly reserved for loved ones. The mostly French team that developed the game clearly spent a lot of time researching the people and culture that they depicted, as the game feels genuine and true.

If games have any superpower, it is surely this one: to show us the humanity and situations of others. And while we use that power usually to offer power, moral questions, and challenge in a fictional world, that superpower can be used to tell the stories of the real world too.

Favorite touch: The writing is tremendous, to the point of me responding to Nour based partially on how I would answer questions from my younger siblings, and getting the response I expected from them from Nour. While the character in the game is not directly based on any real person, the game managed to tell the story of a modern Arab woman in a sincere and genuine way.

Least favourite: The waiting between messages feels awful, and similar to the popular Lifeline series, it is played to tremendous effect. Occasionally, though, it feels like the developers could’ve used a little more bravery in creating an experience that actually more real-time. I understand the game needs some tempo, but I found myself not having the time to commit to conversations as they happened frequently, and thus leaving Nour without a response for extended periods of time. The game doesn’t recognize that wait as a courtesy, but I feel the tension could’ve been resolved with a more real-time application.

Alternatively: There are actually two other games that both deserve the Best Mobile spot. The long-anticipated sequel to Reigns, Reigns: Her Majesty, feels like a leap forward on top of an already fascinating foundation. The other game is Hidden Folks, a beautifully drawn Where’s Waldo game with clever hints and fascinating little stories hidden in its sizable worlds, is a remarkable experience.

Best …: Injustice 2

There are so many other games that I feel are worth a mention. Mario Odyssey’s magnificent design, with an opening that was so expertly crafted that it genuinely made me angry, is one such game. The vistas and world of Horizon Zero Dawn mixed with the never-decreasing threat of robot-dinosaurs. The clever use of verticality as both a reward and means of exploration in Zelda: Breath of the Wild. The painfully human world we live through a cat’s eyes in Night in the Woods. The enormous achievement that is the almost impossibly versatile Divinity II: Original Sin. Pyre’s subtle opening up followed by a ruthless sense of responsibility. The proof that any genre of game can be an RPG in Golf Story. The masterful brawling of Aztez and its genuine lessons of Aztec mythology. The “small” Uncharted game that packed a punch. The atmospheric nostalgia of Hollow Knight. The spectacle of Nex Machina. Oikospiel Book 1’s incredible weirdness. The confusing amusement at the RPG that is Kingsway. I spent hours missing enemies to score points in Splatoon 2, controlling an RTS with a mouse rather than a mouse in Tooth & Tail, and I played Tetris to beat someone at Puyo-Puyo.

But there is one game that I unexpectedly kept coming back to when I had nothing else to play: Injustice 2. This category is my crutch, my way of giving a shout-out to a game that doesn’t fit any other category, but that was somehow important to me this year. Injustice 2 is by no means the best fighting game ever released, but it is by far the most complete fighting game I’ve ever played.

The acting (and performance capture) in it was so utterly convincing, that I played through the story from start to finish at least three times already, and I never got tired of the way the action flows from cut-scene to gameplay seamlessly. If DC wants to know how to make an interesting cinematic universe, I think they might want to look at games rather than movies.

While I enjoy the story and the combat, I adore how Injustice 2 commits to its fantasy of playing a superhero or villain. Nowhere does that show better than in the Clash system, a strange and seemingly out-of-place betting game that can be triggered in the second half of any fight. The two fighters clash, sparks flying as they stare each other down up close. They speak a witty one-liner each, and the bet resolves in damage taken or life healed depending on who initiated the Clash, and how it resolved. It breaks the combat’s flow, stopping the action entirely momentarily, and initially, I considered it bad design.

As I played more, I realized that it was design focused on selling a fantasy rather than the flow of battle. It turns out that in those DC superhero battles, a huge part of what sells the fantasy is those awkward lulls in a fight filled with taunting and joking. You’ll never see a superhero efficiently dispose of an enemy, or a super-villain dispose of a hero without theatrics. That might be what makes the best fighting game, but it’s not what makes the best superhero fighting game.

Injustice 2 entertained me, impressed me, and taught me about my craft. It’s a tremendous game that I would recommend even to those who do normally not like fighters. There’s something special about Injustice 2, a intentional trade-off that might stop the game from being a Great Fighting Game, but it gives the game a soul that few other games in the genre could hope to ever posses. It is worth not missing it.

Favourite Touch: The Clash system, for reminding me that sometimes it’s OK to sacrifice a bit of the gameplay stuff that people want if it helps sell the emotional effect you hope to achieve.

Least Favorite: The combat sometimes feels a bit off, and I think some of it is in the way Injustice 2 is animated. It feels like some of my issues are related to the technical implementation of the animation pipeline, but I can’t quite put my finger on it.

Alternative: Opus Magnum is a Zachtronics Game. If you like Zachtronics Games, you should play it.