When Video Games Feel Like Work (And That's OK)

By Mento 8 Comments

With all this talk about The Order: 1886 being a ponderous five hour rental at best, I began to consider how almost all games have a small amount of content stretched across a much longer runtime, and how in a lot of cases--especially with the open-world games and RPGs I tend to consume--I spend a lot of in-game time doing mindless chores while I concentrate on other distractions. What troubles me more is that I don't actually mind games that do this. I've decided to look at how some recent games I've played felt like work at certain points, and whether or not that's actually a bad thing. It's gotten me wondering about "games that feel like work" and how I've felt about them.

For the sake of argument, let's say there are three tiers of a video game experience if we're going by a work/play metric:

- The twitch shooters, fighters, brawlers and other Arcade style games that are all fun, all the time. These are usually games where the action is relentless and the player must be completely focused on the gameplay. Most games are this, and most folk will tell you that all games should be this. It's a myopic view of the wide range of experiences video games provide, but there's merit to the idea that a video game ought to keep you fully engaged throughout and cut any chaff in the process.

- Games that deal in delayed gratification. The grown-up approach to life is to reserve the parts that are fun to a small timeframe, around which you're working or doing chores. The idea being that the fun parts become all the more enjoyable due to the undesirable effort you've put towards reaching them. In reality, "the idea" is that you need to earn money to live and need to do chores to not starve to death or smell like a hobo's corpse's armpit, but delayed gratification is just one of those things you begin to appreciate about being an adult regardless, like drinking cups full of foul, bitter liquid to keep you awake. Most RPGs and open-world games tend to have a lot of what folk will call "filler", where you're setting up the fun for later with some training, farming or other prep work first. Monster Hunter's the present Dalamadur of this concept, putting players through a rigorous (and tedious) process of procuring supplies, traps, curatives, materials for equipment and other necessary items before gallivanting off with a group to hunt some enormous beastie. MoHu fans tend to consider this lengthy prep time integral to the experience, because it makes the satisfaction of landing a mark all the greater.

- Games that are almost all work, but with the conceit that there's satisfaction to be had in good old-fashioned repetitive tasks and labor too. This tends to be where the simulation genre lives, where the goal is to recreate a person's vocation in a virtual environment for something approaching a versimilitudinous look at someone else's 9 to 5. One could argue that a lot of open-world games are this too, depending on how much time you're spending doing menial tasks. Obviously, if a game feels like this and probably shouldn't, then it is almost certainly failing its chief objective.

The reason I bring this up is because I've played three games this week of a mild simulation bent. However, the games are really just using an unusual vocation (or, in a fourth game's case, the player's own obsessive completionist tendencies) as a comedic framing device for their incongruous gameplay, rather than trying to adapt the profession virtually in any realistic manner. While they all felt like work, to an extent, I do not necessarily mean this in a negative sense.

Grow Home

A Botantical Utility Droid (B.U.D.) is neither a profession nor a thing that exists, but Grow Home's adorable robot protagonist lives to serve his role. It's fairly common knowledge that the word "robot" derives from the Czech word for "hard worker" (so named by Czech science-fiction author, Karel Capek, in 1920), and so BUD's existence is purely to work for the purpose he was built for. In this case, it's to nurture an enormous star plant to the point of blooming, and recover the star seeds it produces for BUD's unseen masters.

Grow Home has a fairly simple premise: grow the plant, ride its shoots into floating rocks filled with sustenance the plant can absorb, and continue to climb the figurative beanstalk to its ultimate destination above the clouds. The QWOP-like controls are both frustrating and endearing, presenting BUD as some sort of unsteady but determined little trooper, whose frequent knocks and unfortunate explosions are warmly (if condescendingly) remarked upon by its caretaker AI "M.O.M.". Climbing entirely consists of putting one hand above the over, using BUD's clamps to gain purchase on any type of material, and much of the game is spent slowly ascending the central plant while a peaceful harmonious beat plays endlessly in the background, punctuated ever so often by the tell-tale twinkle of one of the game's glowy collectibles.

The game is entirely work. Whether you want to quantify that work as the menial labor this tiny robot must perform to achieve its mission, like a horticulturally-focused WALL-E, or the very real left-button, right-button Carpal Tunnel-inducing exertion required by the player whenever BUD must slowly climb up or around a rock or plant to reach their next target, the fact still remains that much of Grow Home is laborious. Sisyphean, sometimes. Despite that, the game has such a gentle and peaceful aesthetic that this arduous gameplay gives way to a Zen-like state of serenity. You work hard to maneuver yourself around a planetoid for a crystal, but the process doesn't ever seem that draining due to its calming visuals and audio. Maybe it's the ever-present (and rather discouraging) danger of falling off, or the vertiginous view as you get past the thousand vertical meters mark, but something about the climbing remains engaging, even if all you've done in the last ten minutes was to ascend to the next teleporter shortcut or moved about three shoots' worth of horizontal growth to reach a single floating rock. It's safe to say that, for as short as the game is, it feels as precisely as long as it needs to be. Or, perhaps, as long as it can get away with before it really does start to feel like a chore.

Still, there's a lot to be said for looking down occasionally just to see how far you've come. Delayed gratification, this game has it.

Weapon Shop de Omasse

Weapon Shop de Omasse follows a rich lineage of RPGs with a twist, in that the player isn't the brave hero leading the adventure narrative and saving the world, but one of the thousands of regular folk who help them in some small way. Often, this person is a shopkeeper, the type that would disperse weapons and armor at a suspiciously reasonable price depending on the hero's progress in the game. It's one of those RPG tropes among hundreds that simply exist because the alternative would be too inconvenient for programmers were it the case, something RPGs have had to contend with for years in lieu of the tabletop format's versatility, but at the same time it's still a field of illogical inconsistencies rich for referential comedy and in-jokes for genre-diehards.

Like Torneko no Daibouken: Fushigi no Dungeon and Recettear: An Item Shop's Tale before it, Weapon Shop de Omasse puts you in the worker boots of a blacksmithing father and son pair, who find themselves suddenly picking up a lot of business as the world slowly descends into chaos precipitating the regular semicentennial emergence of an evil lord. As well as serving literally nameless NPCs who are rarely optimistic about their chances, the duo must also cater to a gaggle of unusual RPG hero archetypes, from a pair of acrobatic twin sisters to a flashy superhero wannabe who speaks in broken French to a lady pirate whom people don't take quite so seriously while she's stuck on land. The pair also contends with their elderly matriarch, Grandma Snow, who frequently walks out of their weapon shop with an enormous battleaxe with which to search dangerous locales for her senile wandering husband.

The game was conceived by Yoshiyuki Hirai, one half of a Japanese manzai duo named America Zarigani. Manzai is a true and tested formula for Japanese stand-up comedy, consisting of a boke (idiot) and a tsukkomi (straight man) who mine various conversational topics for back-and-forth routines. In the game, these roles are served by the son and playable character, Yuhan, who is a bit of a naive idealist who perhaps overestimates the caliber of "hero" who enters his store, and his father and experienced blacksmith sensei Oyaji, who tends to be a lot more grounded and cynical. Their scenes with the customers are presented like a stand up routine, or some other comedic performance, with an unseen audience that provides canned reactions (laughter at jokes, applause whenever Oyaji shows up, hushed gasps when something scary happens). Most of the game's humor is reserved for its Twitter-like "Grindcast", however, which relays what heroes are doing in real-time after you've sent them on their way. It's a very direct form of feedback for all your hard work at the anvil, even if most of it is scripted to happen a specific way (certain NPC story quests are bound to end in failure, for instance). In fact, the vast amount of text in the game is what delayed its English localization by a couple of years.

As for the gameplay, it's simply the same blacksmithing mini-game over and over. The goal is to chip away at a block of molten metal in tune to a rhythm: each hero has their own leitmotif, and the weapons they tend to use have the same ones while forging e.g. Grandma Snow's jaunty alpine track also pipes up whenever you're working on axes. Hitting parts of the block that still need removing in time to the beat grants larger bonuses, as does occasionally reheating the metal to its "perfect heat" level whenever there's a spare moment. It can be difficult to create a weapon that's much stronger than its blueprint, and this challenge is what stops the game from becoming an endless chore. The player can also polish any weapons that have been freshly forged, or any weapons that have been returned after a hero successfully uses them (the shop is a rental service, for some reason), to buff its stats a little higher. It's all in service of ensuring the heroes have the best possible weapon with them when they depart on a mission. Given that the whole game is in real-time, the player is often forced to prioritize the tasks they are doing, ensuring that they continue to be stocked in high-level weapons just in case a hero wanders in asking for a specific type of weapon (and, more often than not, a specific type of weapon that does a specific type of damage: either blunt, piercing or slashing, similar to Shin Megami Tensei's weapon affinities).

Weapon Shop de Omasse, like all the eShop Guild games that Level-5 have put out, isn't a particularly deep game, nor does it have a huge amount of content. Level-5 devised the Guild series as a means of giving a group of designers (and famous video game enthusiasts like Hirai) the means to work their creative muscles with a premise that could stretch for as long as a few hours, perhaps desiring to foster a similar industry of smaller-scale Indie games that are slowly supplanting the expensive but far too samey big console games here in the West. Weapon Shop doesn't outstay its welcome in that respect, and like Grow Home finds the sweet spot between a runtime that's neither far too ephemeral to be worth a purchase, but not so long that it starts to feel tedious. (Though maybe it helps that I'm currently playing it in bursts.)

Roundabout

Revolving limousine driver isn't an everyday job, but Georgio Manos (played by a wordless yet expressive Kate Welch) isn't an everyday guy. Set at some point during the Spinning Seventies (which, of course, followed the Swinging Sixties), the player is tasked with a series of Crazy Taxi-esque passenger delivery requests that sends them all over the various districts featured in the game. It's far from a regular driving game, however, as the environment is designed strictly to be a pain to navigate around in your constantly spirouetting vehicle. It's all in homage to obscure GBA title Kuru Kuru Kururin, with a groovy disco-era FMV twist.

Of course, the most notable aspect of Dave Lang's Turnover is that aforementioned FMV, played by various famous and less famous video game industry figures trying their darndest to either act or not act, presumably depending on which was deemed funnier by the game's developers No Goblin. There's a few faces familiar to duders too, including Harmonix raconteur Eric Pope, Microsoft face Eric "e" Neustadter, No Goblin's director and frequent E3 guest Dan Teasdale and our very own Steve @fobwashed Kim, T-shirt designer extraordinaire. Similarly to Weapon Shop de Omasse, the game has a deep love of performance comedy and a lot of the time you're working towards the next amusing cutscene.

I have to say, while I enjoy the presentation and humor a great deal, I am absolutely awful at the game itself. I regularly come last on the online friend scoreboards and not a mission goes by when I don't explode into a fiery wreck several times over. The game runs like total poop on this computer, even with all the quality settings down to minimum (which isn't fun when the game's 70s presentation depends on a lot of odd visual filters) though I'm not sure it can be entirely held to blame for my inability to steer a twelve-foot long revolving vehicle around obstacles. I actually have fond memories of the original Kuru Kuru Kururin, which received a PAL localization (which explains why the Australian Dan Teasdale's heard of it), so maybe I've just let my spacial awareness skills atrophy since then.

In this particular case, the game only feels like work because I'm having such a hard time with it. Were I little better at the game, perhaps practicing my cornering as I hunt around for collectibles (which I love doing, but preferably with some sort of running total of collectibles left in the area so I'm not wasting my time combing an area already emancipated of all its shiny treasures), I could be having more fun with it. Or maybe crashing all the time is sort of the point, since it doesn't seem to be too much of a detriment. Either way, I'm not yet ready to give up on Georgio and his dreams, as hard-earned as they'll end up becoming.

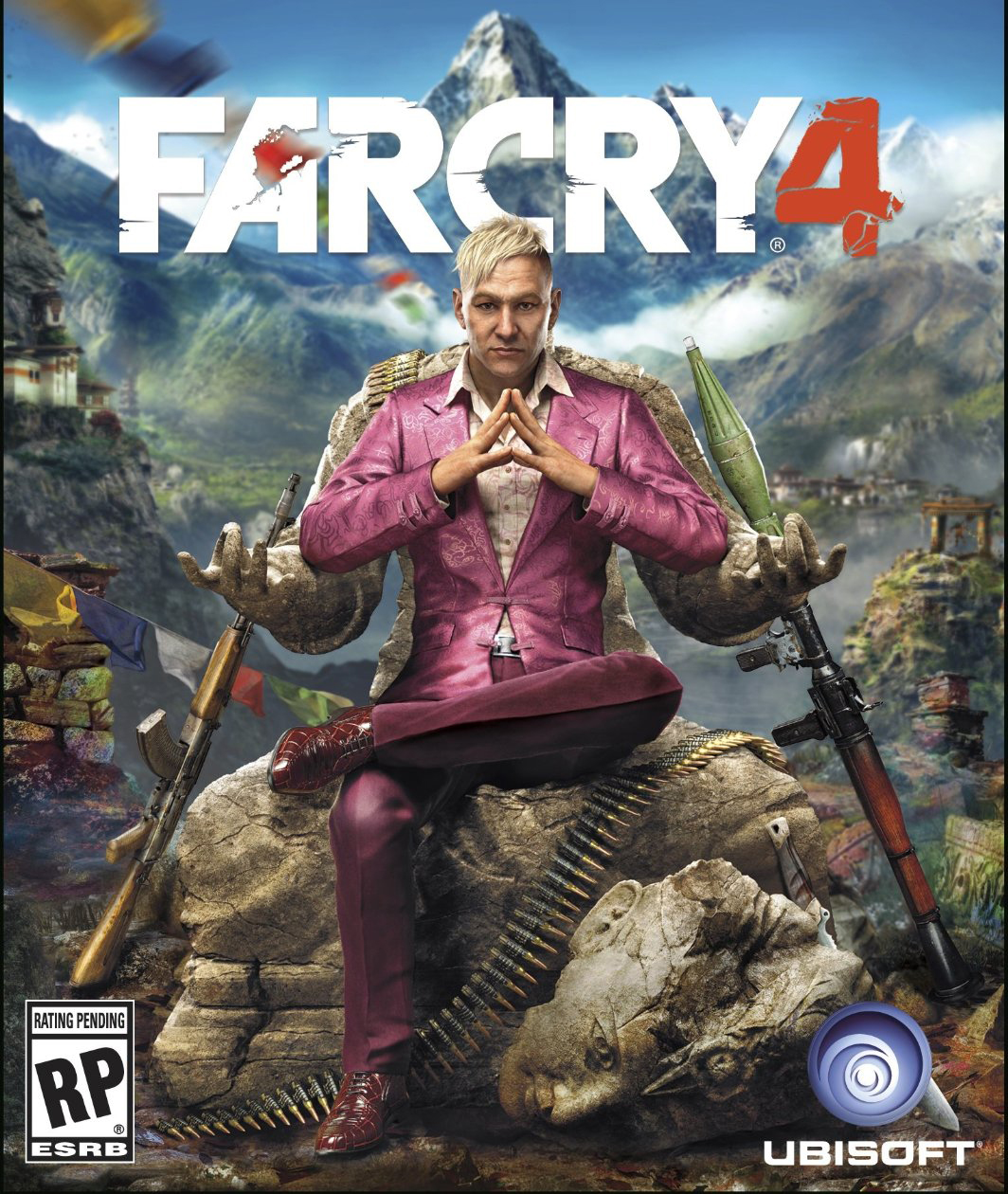

Far Cry 4

Far Cry 4 doesn't really put its hero, Ajay Ghale, in any sort of vocational role except "guerrilla fighter", and that's not the sort of role you can put on the ol' Curriculum Vitae. The game is equally formless, letting the player wreak bloody havoc across the fictitious mountainous Himalayan nation of Kyrat in any direction. Smartly, the game never really makes it clear if fighting the despotic Pagan Min (who, despite clearly being a bit psychopathic and whose opiate-centered repurposing of Kyrat's economy isn't doing the country any favors, hasn't actually wronged you personally) is what's best for Kyrat. You're frequently having to choose between the lesser of two evils whenever assisting the game's central resistance force the Golden Path, founded by Ajay's parents, and much of the time is spent doing errands for other colorful and opportunist visitors to Kyrat who are probably also not looking out for the put-upon Kyrati peoples' best interests.

It's a subversive take on the usual open-world task-a-thons, putting the player in a largely self-driven rampage across a troubled country, blowing up corrupt army officials and endangered wildlife in equal measure. Hard to say that those damn birds don't deserve it, but everything and everyone else seems like collateral damage in a quest for vengeance of which Ajay doesn't ever really pause to consider the necessity. It's also gigantic: the world feels a lot bigger than Far Cry 3's, closer to Just Cause 2's immense island nation of Panau, so when you're a completionist like myself this world becomes a nightmare of obsessive-compulsive icon chasing.

So with this game, it only began to feel like work because I. Just. Couldn't. Stop. Grabbing every collectible, clearing every outpost, climbing every bell tower, completing every side-quest and hunting every animal that I needed to complete my pouches and wallets ensemble. I did manage to stop short of looting the game's thousand or so chests, especially once I stopped needing money, but that 100% completion came at a heavy price to my sanity. I believe this will be the last open-world game I play for a few months, at least until I can work up the courage to all of this again with Dragon Age: Inquisition or Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor.

There you have it, four games that began to feel like work after a while (or did from the offset), but not necessarily four games I would decry or rate poorly for that reason. There's a time and place for a little bit of repetitive gameplay, usually whenever I have a podcast or five that needs listening to, and so I can't dismiss it entirely. Maybe games would be better off if they were all killer and no filler, but there's something to be said for doing something a little more mindless to pass the time too.