The Dredge of Seventeen: October

By Mento 0 Comments

When it comes to game releases every year has its big headliners and hidden gems, but none were more packed than 2017. As my backlog-related project for this year I'm looking to build a list of a hundred great games that debuted at some point in 2017, making sure to hit all the important stops along the way. For more information and statistics on this project, be sure to check out this Intro blog.

With this entry of the Dredge of Seventeen I came through on a threat I made last month. October was going to be a last stand of sorts for this feature (excepting for a moment that we still have two more entries to follow): one big push to get me over the 100-item goal with wriggle room to spare in case I wanted to bump off some of the lesser Dredge entries from the finalized list. With six new games added to the 2017 GOTY rankings we've done just that: the grand total now sits at a very handsome 104 games going into November. That said, I sadly didn't quite get to all the horror-themed 2017 games I had prepared, but I think writing about six games in one entry is probably overkill already and what's more Halloween-themed than a surplus of killing?

It's also been a very dense month for adventure games. With the exception of the Zelda-like Hob from Runic Games, each of the following items were of the adventure genre, albeit often very different interpretations: Another Lost Phone, the follow-up to previous Dredge candidate A Normal Lost Phone, uses the uncommon (for games, at least) interface of a smartphone for its epistolary clue-gathering puzzles; Eponymous is an ominous walking simulator in a Minecraft-inspired blocky video game world stuck in a beta phase; The Letter is a dyed-in-the-wool horror visual novel (and moonlighting as this month's VN-ese Waltz entry); Detention is a 2D survival horror game that eventually drops the spook-evading aspect; and A Mortician's Tale is a macabre but heartfelt puzzle game somewhat inspired by those Trauma Center games from Atlus.

An eclectic mix to be sure, and another indication if more are needed that the year still has plenty of surprises left in store.

Another Lost Phone: Laura's Story

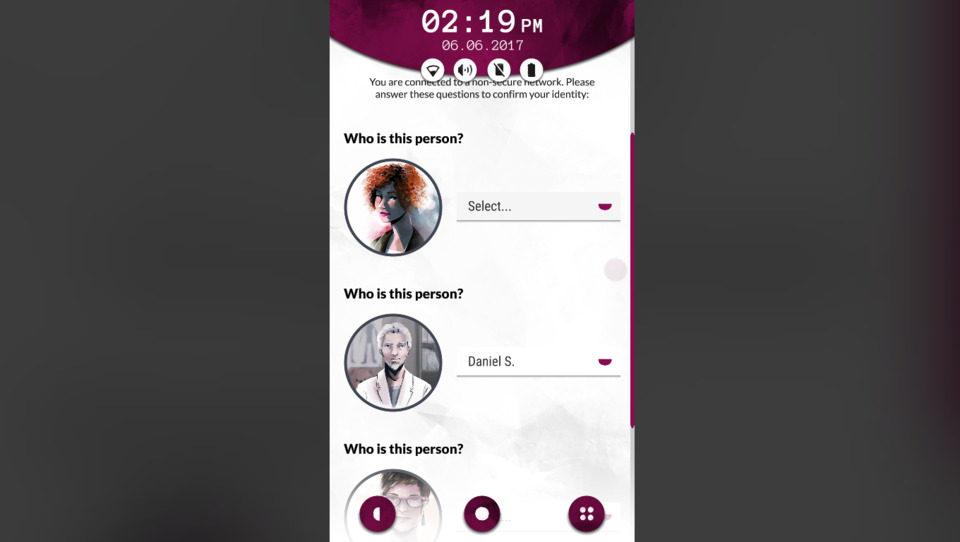

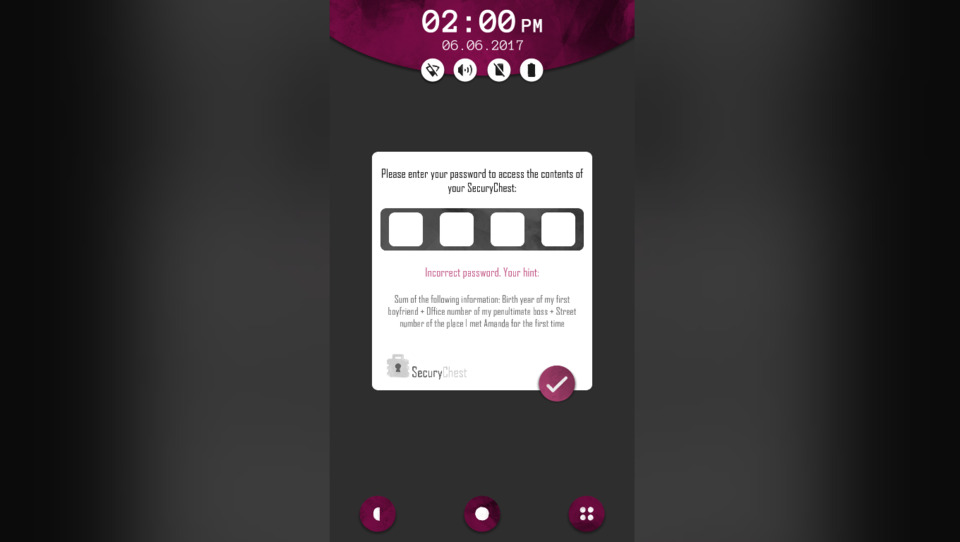

I have a small stockpile of 2017 games that, for whatever reason, released the same year as their predecessors, so my strategy was to play one early in the year and the other late to give them some breathing room. Another Lost Phone is one such same-year sequel for A Normal Lost Phone, which I played back in February. The quirk of these games, one shared by similar series Simulacra, is that the entire "world" is seen through the screen of a single smartphone: the apps are your levels, the passwords your broken bridges, and the treasures are the nuggets of personal data you're trying to mine to understand who the phone's owner might be and how you might get in touch with them to return their device. There's obviously a voyeuristic aspect too, and the game plays a little with that by how willing you are to interfere with the owner's life: there's a button right on the phone's home screen to summon the owner's partner to come pick it up if it's ever misplaced (though there's a few hoops you need to go through to get it working, such as activating the GPS), and it sits there tempting you to take the quick and less invasive option rather than go digging yourself for the info you need.

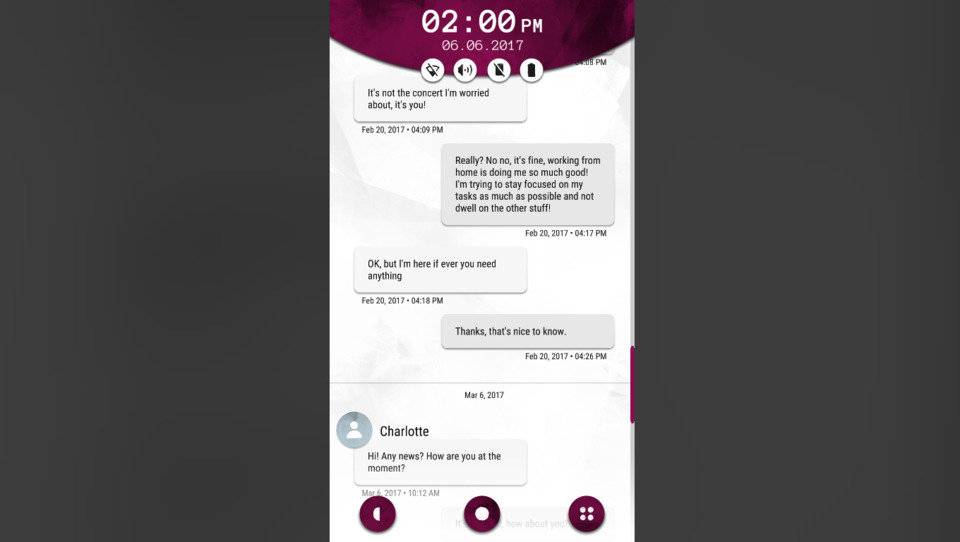

Both Another Lost Phone and A Normal Lost Phone are built on twists and secrets: the key to their mysteries can be found by unlocking the path to the owner's most secret sanctuaries and learning the truth behind their current predicament and why they may have abandoned their phone in a hurry. That also means that a review like this has to tiptoe around those revelations, focusing on the means in which it delivers that story without being overly descriptive. The surface-level correspondence paints a picture of a young female professional who has been estranged from her closest friends with the exception of her current squeeze, the picture of a supportive and caring boyfriend. Of course, there's a few hints that he might not be as he seems, and the more emotionally intelligent players (or those with similar experiences) can probably pick up what's going on relatively quickly before the game makes it explicit.

Another Lost Phone first has you looking for a public wi-fi password in the images and conversations saved to the device, moving onto social media websites and email once an internet connection has been made, and finally a private messaging app with several layers of secrecy obfuscating its presence. Each lock requires careful examination of the information presented in the apps currently available: a saved image providing a street address, for example, or an email correspondence that reveals a relationship between two contacts that isn't made explicit elsewhere for the sake of answering a security question. It's clever stuff, requiring some logical deduction, reading comprehension, and observational skills: aspects of a player's potential perspicacity that adventure and puzzle games don't commonly invoke. The interface is pleasant too: while revolving around a piece of modern technology, the art style has more of a hand-drawn feeling with softer edges to the displays and more calligraphic fonts in lieu of whatever cold and mechanical defaults are the norm with phone manufacturers. This softness also helps alleviate the pervasive wrongness that is present whenever a game tasks you with delving into a stranger's personal business: while your avatar has no bearing on the story and thus has no evident intent or interiority to define them, the game's stated goal is to help Laura in whatever way you can, and that means learning as much as possible about any predicament she might be in before deciding on a course of action.

Like A Normal Lost Phone, I found Another Lost Phone a compelling mystery framed in a fairly uncomfortable delivery method. Uncomfortable both for my aversion to smartphones and to privacy invasion alike. That doesn't necessarily serve as a knock against the game - art is often about taking you out of your comfort zone, after all - but I feel this game might be better appreciated by those who live in their smartphones and are more familiar with the territory. And, to be fair, that's like 95% of people my age or younger, so I can definitely see this adventure game format continuing to propagate as a means to tell chilling, personal stories about potentially imperilled individuals: it's like the opposite side of the coin to how horror stories have to either write around the fact that everyone can call for help on their phones at any moment, or else have to make them '80s period pieces where we're too harangued by knife-wielding stalkers to spin a rotary phone the necessary number of revolutions.

Ranking: C. (It wouldn't feel right to put this too far away from where A Normal Lost Phone will end up on the list, given all their strengths and weaknesses are identical and the dawning realization of their twists are delivered in a similarly effective slow-burn fashion. If anything, they function as a double helping of the same meal.)

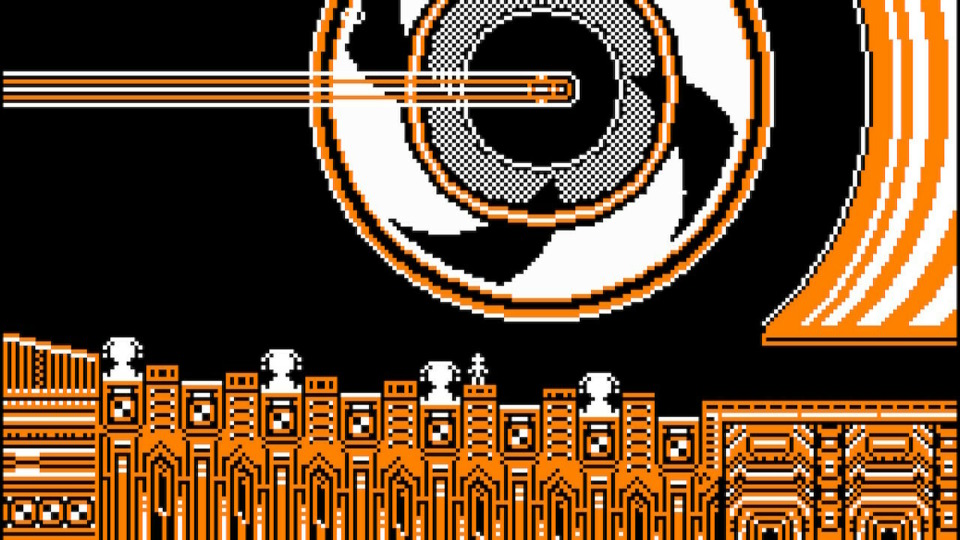

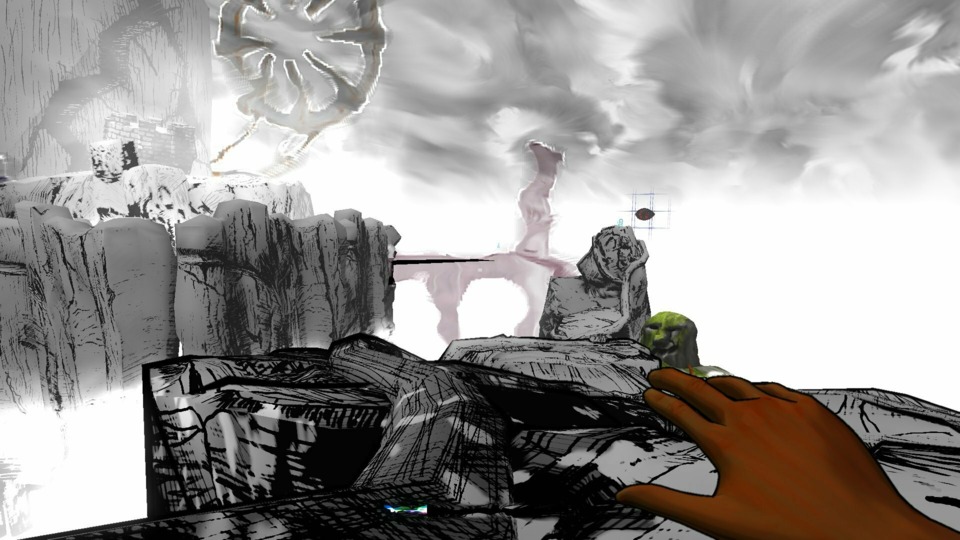

Eponymous

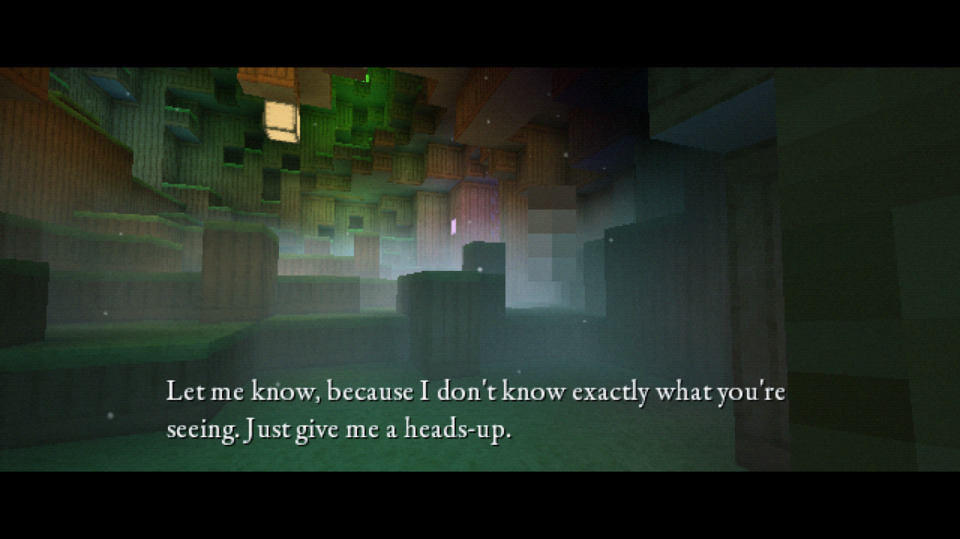

I added Eponymous to my reading (?) list after playing a different game from this studio for an Indie Game of the Week (Minor Key Games and Super Win the Game, respectively) and wondering what kind of range this developer had, given the IGotW in question was a Zelda II-inspired explormer. Eponymous is... well, hard to define, but it's a walking simulator combined with explormer type advancements - say, acquiring a crouch or double-jump move in order to explore more of the world - set in an ominous and surreal world made of Minecraft-style lo-fi blocks with a meta twist in that the game's programmer is frequently talking to you, guiding you through what game there is like they might a QA tester during an alpha phase of development.

Eponymous, or "Eponymous: In Which a Work Is Known by Its Reading" to give it its full title, feels like an experimental palate-cleanser between projects: a notion that the developer had and turned into a short piece on a whim. Excepting any amount of time spent wandering around lost, the game takes about thirty minutes for a blind run at most. It's not wholly a walking simulator, despite what I said in the lede: there's some platforming involved, though it's relatively minor and unintrusive if you're not adept at those games (or their 3D incarnations, as is the case here), and the game mostly serves as an unsettling tone piece. As you play, you catch glimpses and sound glitches of a potentially malignant entity: one that goes unacknowledged by your voiceover guide. This being manifests in the game as a shape with a heavy pixel-mosaic that causes visual and audio distortion just by looking at it, similar to the titular antagonist of the Slender games, though is otherwise a passive observer of your actions that cannot be interacted with. This entity will speak to you also, often providing conflicting information to the developer voiceover, and as the game gets more bizarre with its environments it becomes a little bit of a psychological horror game where you're left considering who to trust, especially as the stranger of the two voices is frequently warning you of danger you cannot yet see.

While the game isn't terribly involved or compelling, with its levels of abstraction often working against it as much as for it, if you chance upon it for free like I did (its normal asking price is around the $2-3 range though, so you're not breaking the bank either way) it might be worth seeing it through to its twisty and enigmatic conclusion. I might argue that the game is meretricious by design: the horror, the platforming, and the narrative are all paper-thin, but the actual aesthetic of an empty and half-complete video game world with a potential ghost in the machine makes for a quite striking setting to just wander around in, offering strange little passages to read for those who explore all its nooks and crannies. It did make me wonder if the developer intends to do something much bigger with the concept one day, and is simply testing the uncanny valley's waters here.

Ranking: E. (An intriguing interactive short with some novel ideas but not much in the way of mechanical depth. It won't threaten any of the more elaborate games on my list, but there's enough substance to its ominous oddness that I can't dismiss it entirely either. It can sit in the "I'm not sure what this is" zone, otherwise known as 81-100.)

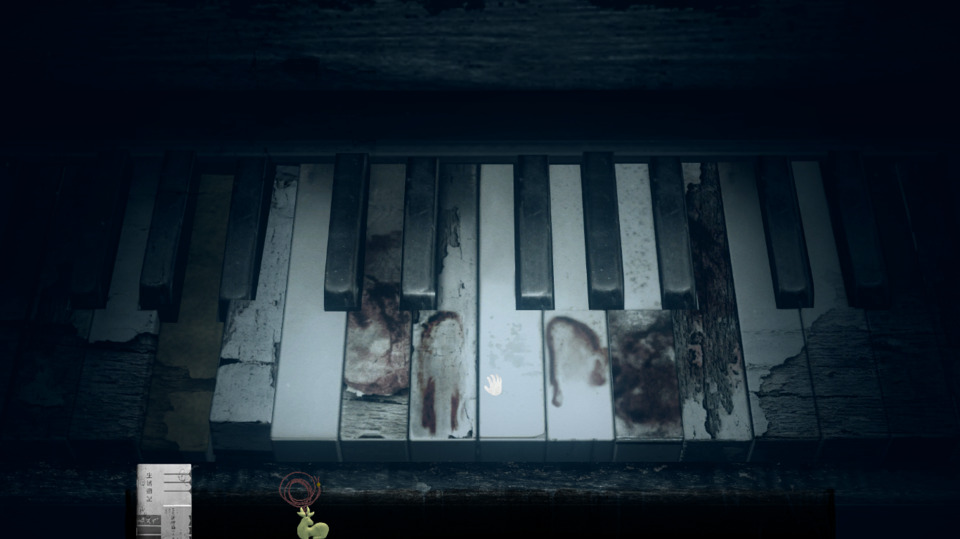

Detention

So I didn't know this until planning this month's 2017 itinerary but Detention had a live-action movie adaptation? The movie originally came out in 2019 but Netflix started promoting the localized version over the past month. Hearing about it made me more determined than ever to get into this Taiwanese horror adventure before the end of spooky season, on top of it being a well-acclaimed slice of psychological (and political) horror.

Set in the politically tense environment of 1960s Taiwan, a dozing highschool student named Wei wakes up in the late afternoon to find his school abandoned due to a typhoon warning. Wandering around he meets a senior, Ray, unconscious in the school's auditorium. Realizing that neither can leave because the bridge has been washed away, the two buckle down for the night until help can arrive the following morning. However, something in the school suddenly shifts, leaving Wei mysteriously dead and Ray the only survivor, prompting her to start looking around the school for answers. Early on, Ray must evade the notice of malicious spirits roaming the school by following the instructions left behind in notes, but as the mystery behind her predicament deepens the game's direction shifts in turn.

Many horror games from countries less represented in the gaming industry will often draw upon their folklore and culture as a means to distinguish themselves from the crowd, summoning any number of local creatures and spirits as the antagonists, but Detention goes a step further by setting the game in Taiwan's White Terror period in the 1960s, roughly analogous to the McCarthy communism witchhunts but with a much more aggressive government mandate behind it, and couching the game's supernatural evil in an all-too-quotidian malevolence. Anti-communist sentiment was strong enough to get you killed if you were found to be in possession of banned texts or espousing certain values, and the literati of the era found themselves stifled creatively and intellectually by these oppressive laws: it works effectively as the backdrop to the game because of how it factors into the more personal story of its protagonist, Ray. The particulars of this tale are doled out very gradually and often through subtext rather than directly: the Ray the player controls has a selective memory loss of the events surrounding the time when she meets Wei during the typhoon alert, but eventually starts to remember as the player explores the school and beyond its walls.

Its structure is similar to Silent Hill 2, in that the titular foggy town is less of a real-life entity and more of a metaphysical construct of the protagonist's tortured mind, with nonsensical geography that works mostly to funnel the player from one moment in Ray's life to the next. The game has its monsters, all of which must be evaded somehow, but these too aren't entirely real: in fact, they simply stop appearing after the halfway point of the game, relegated to an afterthought once the true nature of this illusory world becomes evident. I suppose it's a bit of a spoiler to give away this progression, but it's not exactly some late-game exclusive happenstance: the game's shift in purpose and design happens gradually throughout its early, middle, and final chapters, and is key to its appeal as a contemplative horror game that's not so much swimming in supernatural chills than it is about exploring its protagonist's interiority.

As far as the gameplay goes, though, I was consistently impressed with the type of puzzles Detention had to offer. They start as relatively benign key puzzles common to the survival horror genre - explore from one end of the available areas until you find an item, go back to where it's needed, try to survive the spooky scenario that arbitrarily triggered as a result of your actions - but start getting weird, befitting the dream logic rules of this abstract world. One such instance includes turning a radio dial to different stations, each time causing the world to shift: one has you exploring Ray's home as it once appeared to her, while the next moves all the furniture to the ceiling and walls and generates new areas to explore. A mirror puzzle a little later on has you changing the lighting to suit the reflection's behavior. Despite the increasingly surreal and obtuse situations behind these puzzles, they remain approachably intuitive to solve throughout. The ghost encounters too are fairly novel in their mechanics: the first type simply requires you to hold your breath (toggled by hitting the right mouse button) and pass quickly by before you run out of air, while the next requires you hold your breath, stand perfectly still, and not make eye contact by looking in the opposite direction as it walks past. They vanish after that point though, so I'm slightly curious how much more elaborate the evasion strategies might've become if they had stuck with it.

Detention's strengths are in its slow reveal of what Ray did to lead her down this disturbing trajectory and its use of mature themes of (minor spoilers) abandonment, loneliness, political upheaval, sexual awakening, seeking redemption, and ugly emotions spurring uglier acts of defiance and suffering as the background to the game's central intrigue. However, mechanically as a survival horror game and a standard adventure game alike the game is surprisingly strong as well with multiple inventive puzzles and a ghost evasion tactic more nuanced than "run the other way;" certainly more impressive than most 2D Indie Silent Hill ersatzes I've played in the past. That a genre such as this, which nominally exists to give YouTubers a histrionic fright or two to the amusement of their audiences, can produce a game with such solid mechanical and emotional cores alike is a rare and wonderful thing. I'm clearly going to have to try their follow-up, Devotion, before too long. (I just hope it finds its way back on Steam or GOG eventually once they grow a spine, though there's always the developer's own site if all else fails.)

Ranking: B. (I'm not a particular fan of survival horror games because they tend to be one-trick-pony jumpscare delivery systems, even the more interesting ones like Siren or Fatal Frame, but Detention works in that space better than most in part because it has a grown-up tale to tell about living in the wrong country at the wrong time in its history. To witness the abuse this developer has gone through, Detention's bogeyman of oppressive regimes censoring anything even mildly critical is as potent as ever.)

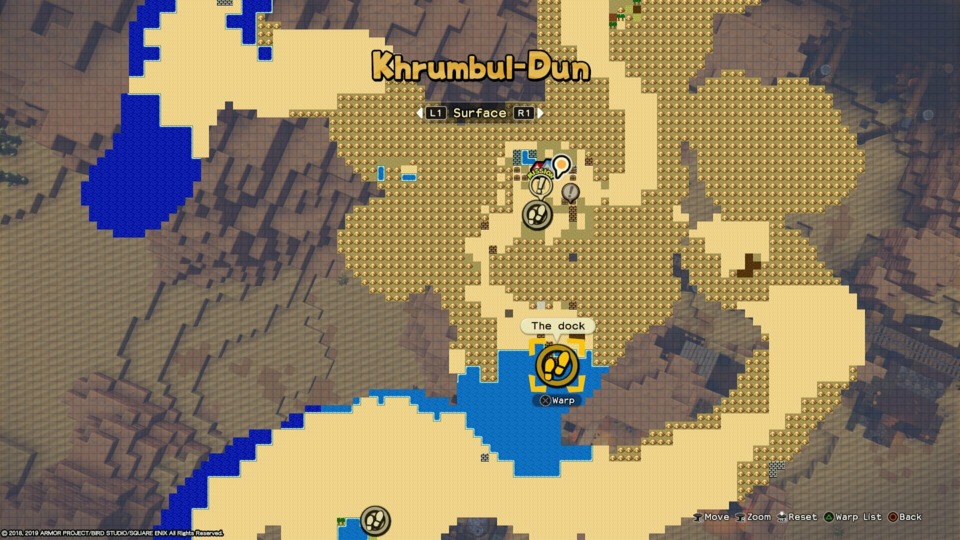

Hob

Probably the game with the highest profile of this month's batch, Hob was an attempt by Runic Games to branch out after the second of their Torchlight loot RPGs. Sadly, the studio closed down months after Hob's arrival, though I suppose we should be grateful they managed to get the game out before that happened. Hob has some obvious parallels to the Legend of Zelda franchise, adapting a similar angled top-down perspective and exploration occasionally gated until the player had solved a puzzle or found an upgrade.

However, perhaps unconsciously channelling the recently released Breath of the Wild, Hob offers very little in terms of dialogue or lore or direction: rather, what it does offer is subtext and hints to the current state of its mechanical world. One glance of the setting of Hob would suggest an untamed, arboreal world with alien flora and fauna, but some rudimentary exploration is enough to prove otherwise: much of the planet, beneath a veneer of grass and nature, is entirely mechanical. Switches raise and lower artificial landmasses covered with intricate, arcane designs, and almost every NPC you meet occupies a robotic frame. It's also covered with a sinister corruption of extraterrestrial origin, which glows with a bright blue and purple sheen which creates a stark contrast against the natural greenery of the less effected environment. The protagonist, a hooded figure, is one of many of its kind: all the rest of whom appeared to have been taken over or destroyed by the malevolent corruption and its approximation of a hive intelligence.

Hob has something of a dichotomy behind its world design and progression. While it does little to hold the player's hand beyond offering a point on the map to head towards, there's not much in the way of open-world exploration. You can wander off the beaten path only to find obstacles every where you turn until the current objective has been met, which'll often reshape the world in unpredictable ways to make more of itself accessible. One example is fixing a water plant and opening a series of pipes, which fills empty reservoirs with lakes and rivers, allowing your protagonist to cross to the opposite banks and continue exploring. There's plenty of collectibles and upgrades to find off the beaten path, mostly involving the game's skill system: any new skill requires both the blueprint to add it to the store and the currency needed to then buy it, the latter also dropping from larger enemies. In addition are the requisite health and stamina upgrades, the former needing two and the latter needing five to upgrade the respective gauges. There are also butterflies, which are the more elusive types and serve to unlock some of the double-edged alternative costumes, each of which improves either stamina, attack, speed, or health at the cost of another. Finally, there are the vista points: places to stand that causes the camera to zoom in on the more scenic regions of the game, adding to the game's pool of concept art. These vista points can be hard to spot, however, due to their small size. Most collectibles will appear on the map as icons if you were unable to collect them the first time (vistas are the exception, which conversely only appear on the map after you've accessed them): most of the time, they're not so much locked away by a missing upgrade but simply because the player needs to find another route to reach them, possibly one that has yet to be opened. Since subterranean areas are smaller they lack maps, but in its place you have a set of icons that correspond to all the collectibles in that area for the sake of completionists.

The world design, though attractive, can often obfuscate finer details that deserve to be a little more apparent. While the game does give important interactive objects a slight sheen to help distinguish them from the background, the world can often be an awkward place to navigate. Pathways route circuitously over and under the landscape in ways that aren't always obvious, especially with the fixed perspective. The game puts this to effective use when hiding its valuables from all but the most observant and thorough explorers, but it's less welcome when the path to the current objective is the one being obscured. Other irritants include the way the map zooms in when fast-travelling to make it harder to understand where fast-travel stations are in relation to each other; you can then manually zoom back out, but it's an odd choice for the default option. There's also the inconsistent respawn rules: most of the time, if you tumble down a pit you'll respawn right next to it or at the entrance to the current room as in Zelda, with only full HP loss requiring you to return to the previous checkpoint. However, the game is annoyingly inconsistent about this rule, dumping you some ways back if you're trying to hop over to an out-of-reach collectible or some other daredevil platforming challenge.

One of the game's shining virtues is its combat, which is layered in a way most Indie Zelda clones don't bother with. Combining aspects of the top-down 2D Zeldas with the later 3D ones, you have a standard sword swing, dodge roll, and enemy lock-on initially but are continually adding new moves and abilities to your repertoire as you find and purchase their blueprints. This might be a simple extension to your regular combo, a stronger stabbing move that is performed while sprinting, or something based on new abilities: using the grapple hook to pull off armor plates, for example. Through this system of incremental advancements, the combat remains compelling throughout if never super involved in terms of unique enemies and boss fights. The puzzles are inventive too, and there are many dungeon-like structures and other set-pieces that involve multi-stage puzzle-solving, like restoring the aforementioned water system or climbing up a massive tower of gears. Reviewed on their own, these aspects sound like they make for a strong game, though the relatively minor irritations combined serve to detract from the moment-to-moment experience of actually playing it. It certainly doesn't seem like the game was rushed at any stage given the intricacy and relatively large size of its world; it simply doesn't coalesce in the way it probably should, considering all its parts on an individual basis. Its wordless presentation also serves to work against it more often than not, creating a layer of narrative obfuscation - where the player simply goes from place to place completing objectives for reasons unknown until later - in a world more deserving of some detailed backstory. The hands-off approach is a bold choice though, and a relatively unusual one, so I can't fault that particular aspect too much: I'm the kind of dumbass who reads all the books in Elder Scrolls games and item descriptions in Souls, so maybe the issue here is more internal.

Ranking: C. (I enjoy most "Zelda-likes" and I think Hob is a spirited attempt to make a moderate-budget one of those with an impressive length, art direction, combat systems, and puzzle design: all the ingredients a game of that genre needs. It just felt a little soulless and rudderless to play for reasons I can't wholly put into words, pushing me through the motions of completing the game's railroaded objectives while never being quite so burned out by the process that I didn't pause to take the time to poke around every currently accessible area looking for secret caches and other surprises. Like a fulfilling meal rather than a delicious one, perhaps is one way to put it. It's going to end up square in the middle of my overall rankings once I'm through, I suspect.)

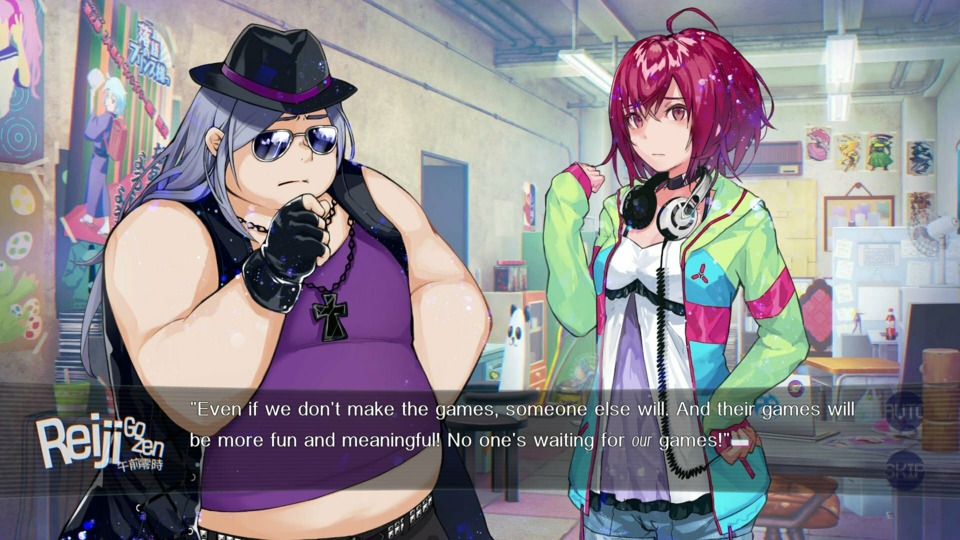

The Letter

(I reviewed The Letter in more detail in this blog. This entry is a continuation of that review, discussing the multiple routes and endings with as few spoilers as possible. Best to consult that one first if you want a more general rundown of the game, but here's a brief synopsis for the sake of clarity: as one of seven people cursed by an old chain letter found in a haunted mansion, the player must try to survive ghost attacks while working out how to free themselves from the curse. These seven characters include Isabella Santos, one of the estate agents looking to sell the mansion; Hannah and Luke Wright, the affluent couple that buy the place; Marianne McCollough, the interior decorator hired by the Wrights; Ashton Frey, a police detective friend of Isabella's; Rebecca Gales, a schoolteacher friend of Isabella's; and Zachary Steele, a photographer and filmmaker friend of Isabella's.)

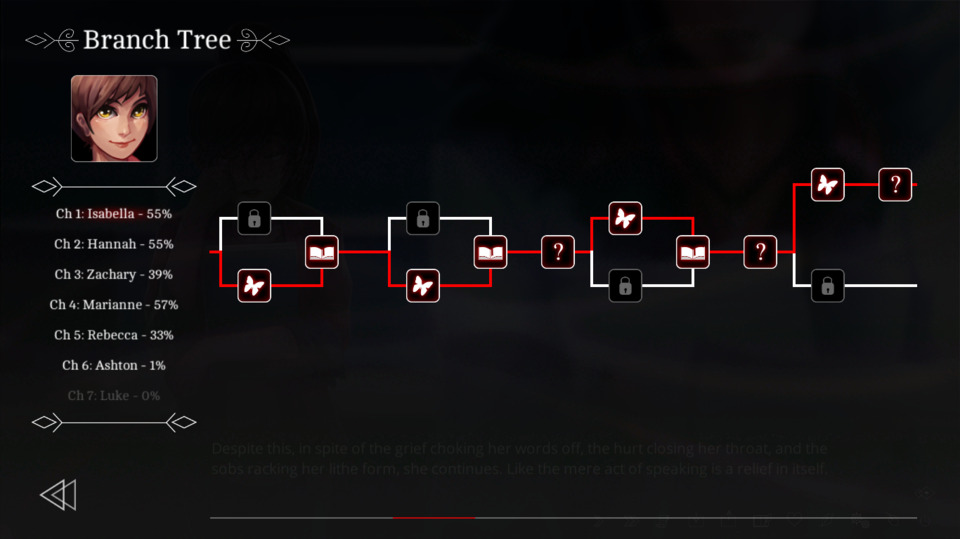

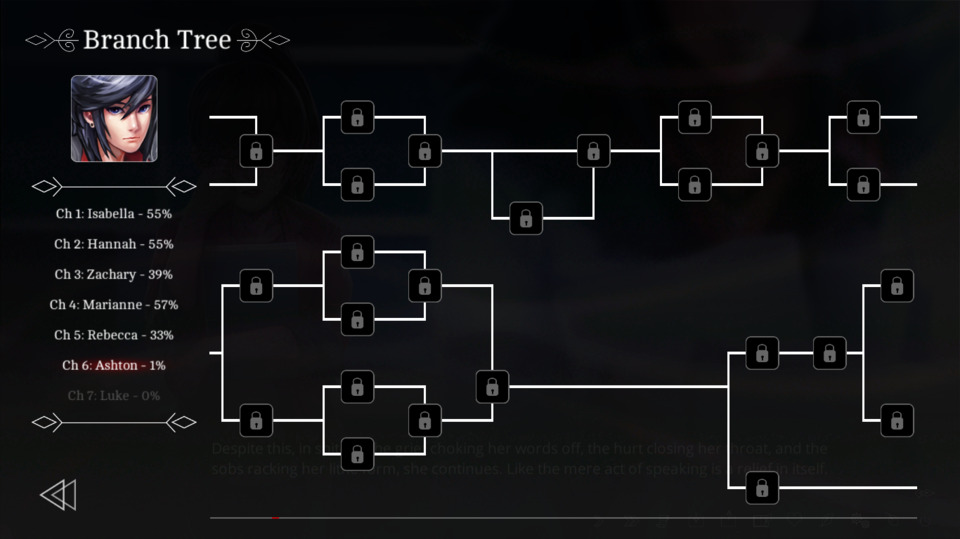

I've now completed The Letter three times, seeking out its elusive "true ending" and discovering more about how the game is structured. Similar to Raging Loop (covered here), there's merit to seeking out endings where characters die: every chapter, each of which has a different viewpoint character, can either end with that character's death to or narrow escape from the Ringu-esque spectral antagonist (who, is turns out, actually was a Japanese woman. So I guess it isn't appropriation after all?). These fatal endings unlock "memory fragments," that are accessed by the final viewpoint character, the caddish Luke Wright, due to some genetic memory tying him to the cursed mansion. By playing through routes that leave characters deceased, the player can witness Luke's recalling of the memory fragments attached to those characters' fates and learn more of the backstory of the game. Once enough information is gleaned, you should theoretically realize the "correct" combination of characters to kill off for the game's true, if not best, ending. Alternatively, you can seek out the game's many epilogues, each of which based on the following variables: each character's relationship status with the other characters, and whether or not that character perished. There are, for instance, ten different versions of a "romantic" epilogue which rely on those two characters maxing their affinity with one another, though only for certain combinations of characters (for instance, there is only one same-sex coupling in the game).

To emphasize just how many variables the game is juggling, the Steam version of the game has 172 achievements. I initially wondered if it was one of those games that gave out achievements every ten seconds as incentive to keep playing or whatever that scam is about, but each achievement is actually connected to a specific CG or event that you can only trigger by choosing specific decisions during the story, plus a few more general ones like completing every ending for one character's chapter or nailing the QTE ghost attack mini-games. After three playthroughs I've achieved barely over half that number: some are going to rely on some very specific routing, which helped me realize just how complex the game's branching system is. Even if you're not a fan of the "Choose Your Own Adventure" format most visual novels seem to follow, it's both admirable and a little bewildering just how intense the branching is in The Letter. Luke Wright's chapter, which is also the last, is relatively short: the game's denouement begins just as the previous character's chapter ends, and after some backstory to establish Luke's role in the story you see the game out from his perspective. However, for as relatively short as it is to read, the flowchart for Luke's chapter is easily ten times longer than Isabella's, the first. It has to be, to account for every variable: who died, who is closer or more distant to whom, whether you decided to talk to this NPC or that NPC, etc..

All that said, I think there are some plotting issues with the game and some very strange character choices that probably needed rethinking. For instance, as if to establish that Luke Wright isn't a particularly nice person, he's the only character in the game that freely drops racial slurs around the game's minority characters Zach, Isabella, and Ashton. In some ways this makes sense: Luke's a ruthless businessman raised by a heartless tycoon and has killed (or had killed on his behalf) several people that threatened to derail his financial empire, though the player can choose to help him realize his more empathetic side through his interactions with his wife Hannah, but slurs feel like something that a medium shouldn't need to utilize to make the point that a character is a villain. The fact that he gleefully murders Hannah on one of his routes should be enough to establish his villainous bona fides. To the game's credit, whichever characters he's with immediately call him out on this behavior, including - perhaps incongruously - the corrupt Chief Inspector of the city police. Some character deaths are the result of boneheaded decisions, making them obvious death flags for anyone who's seen a horror movie, though others are a bit trickier: Hannah, for instance, will be possessed by the antagonist if she's too forgiving of Luke's actions and will be murdered by him if she's too hostile - the only way she survives to the end-game is by being somewhere in the middle, acknowledging that their marriage is on the rocks and could use either a trial separation or couples therapy to resolve.

Now that a single playthrough will take in the region of an hour or two given most of the dialogue can be skipped - excepting route variances I've not seen yet, since the fast-forward feature won't skip past any new text - I might find myself jumping back in to check out what happens if certain characters don't make it to the end. I've yet to try a run where everyone dies, for instance, or one where everyone lives for that matter (my first and third attempts had one casualty each). I'm not sure I have it in me to play through the game the 30 or more times it'll take to see every variance, but it does turn the game into a little collectathon of sorts: how do I access that one branch of unseen events? What kind of far-reaching consequences does this choice have? How many character pairings can I find? I might bounce back in occasionally to try a new route if the inclination strikes... though it's more likely I'll get distracted by something else this November, including the next visual novel.

Ranking: C. (A dense structure doesn't necessarily make up for a clichéd ghost story, even if the characters are mostly well-realized by their individual chapters and the script relatively engrossing in its delivery. The art and animations are generally decent, the latter more so due to how effectively it's utilized for the jumpscares, and I'll admit that there's some part of my lizard gamer brain that is compelled to hunt down all those different route variables and CGs and achievements, and the game sure has a lot of all three if I wanted to talk up its longevity potential. The Letter couldn't quite evoke the same emotional response that something like The House in Fata Morgana did - which has many plot similarities, not least of which being the central haunted mansion and a raven-haired maid spirit - but I'm positive enough towards it that I'm sure it'll find a firm placing in the middle tiers somewhere.)

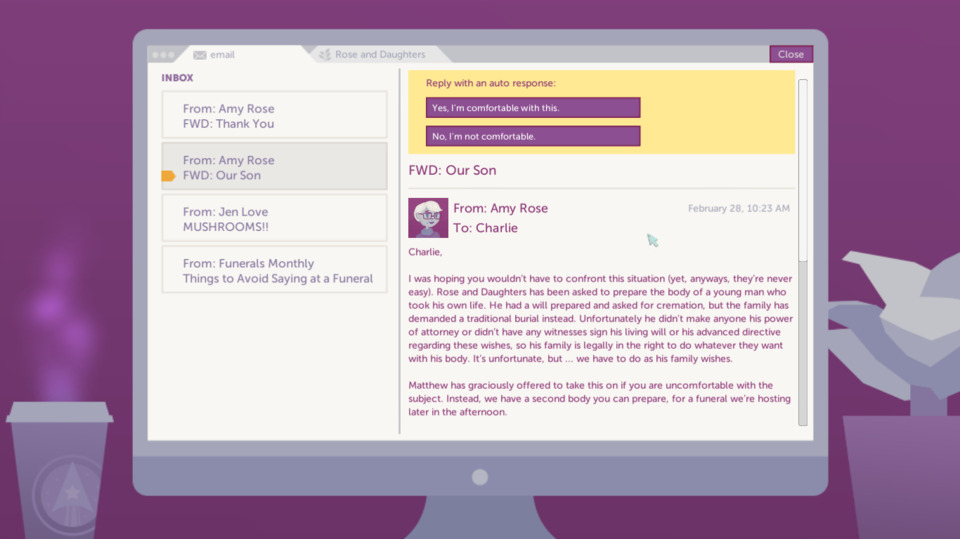

A Mortician's Tale

Our final October entry is a game that isn't strictly Halloween or horror-themed, and in fact calling it such might be a disservice to its death-positive message of empathy and unity in the face of loss. A Mortician's Tale has you, as funeral director Charlie, preparing bodies for burial or cremation for bereaved families, working with them to provide the type of service that'll best help them with their grief. It's a sweet-natured narrative adventure game that handles its subject matter with the sensitivity it deserves, delving into a part of life - the last part, specifically - that most media is hesitant to touch.

Each of the game's small "chapters" begins with Charlie checking her emails, which along with the new assignment also includes correspondence with Charlie's university friend Jen, now working as a forensic scientist in a museum, as well as with the other employees at her funeral home. These little asides both work as a means to provide little side-stories for you to follow over time, as each "chapter" is separated by several weeks and months, as well as explain more of what a funeral director's work entails and the decorum and conventions related to funeral services and interring the deceased. The educational aspect comes from Charlie's subscription to the "Funerals Monthly" newsletter email, which also discusses what to say and not say to mourners, alternative means of laying a person to rest including eco-friendly "green" funerals involving biodegradable chemicals, and how different cultures handle death including the colors worn at funerals.

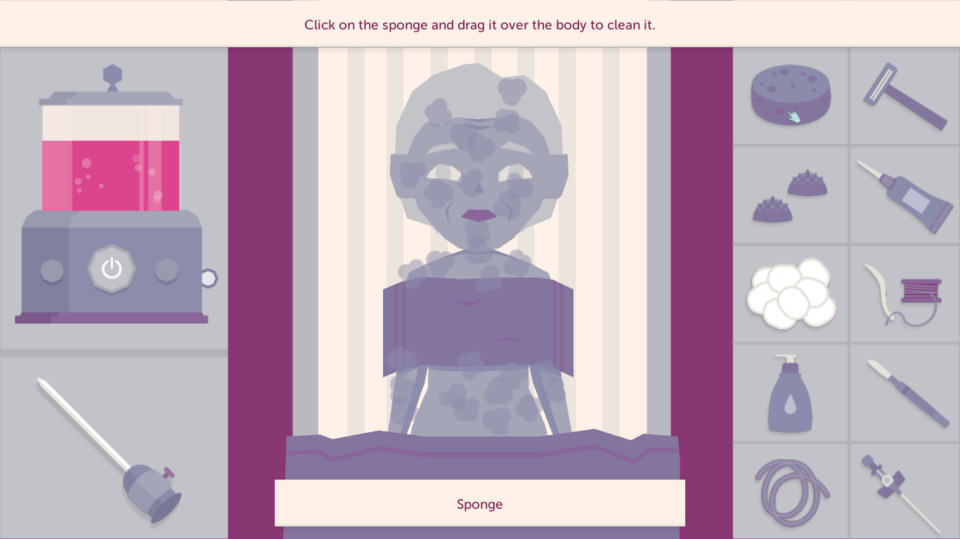

Following the acceptance of the new assignment, the player must then prepare the body. This plays out a little like the operations in the Trauma Center series, following a standard series of processes using a sidebar of tools. If the body is to be preserved for an open-casket funeral, for instance, you need to carefully clean and massage the body to preserve the skin, drain the blood, and inject it with formaldehyde to ensure it's presentable for the service. Fortunately, there's no part where you need to do reconstructive surgery on someone who walked into helicopter blades or something equally unpleasant - no having to work on a "Timmy Headloaf" - but there are a few complications that arise with some cases. For one, you have to surgically remove a pacemaker before cremation to ensure it doesn't explode mid-incineration, while other items like jewelry need to be removed from the cremation process and added to the urn afterwards. Each of these body preparation mini-games have full step-by-step on-screen guides so there's no point where you need to memorize the process: these mini-games aren't really about challenging the player with increasingly difficult scenarios, only serving to demonstrate the type of process bodies go under in preparation for their funerals in a hands-on fashion. Finally, there's the funeral itself: you are free to talk to mourners to gauge the type of person the deceased was, or simply pay your respects at the coffin/urn and return to the lab area for the next chapter of the game.

The game's relatively brief - about ninety minutes total if I had to guess - but there's a few asides like a death-themed minesweeper clone that your friend sends you. One case gives you to option to skip if you feel uncomfortable with it: a suicide victim, whose final wish to be quietly cremated is superseded by the family who prefer an open-casket funeral instead. You're given an alternative case to handle instead if you choose to pass on it. The developers' intent is quickly obvious when playing: not only to remove the stigma surrounding death and celebrate those whose job it is to see us out with dignity and respect, but to detail the day-to-day processes and the challenges that funeral directors and technicians face. The game's overarching plot, which eventually sees Charlie's "mom and pop" funeral home change hands to corporate ownership and adopt a clinical and profit-focused approach to services, is handled well and highlights the importance of empathy to those grieving. Its wholesome aesthetic does much to soften the morbidity of the subject matter - the deceased look a lot like Animal Crossing villagers when they're on the slab, come to think of it - and I'm a mark for any game that opts for an isometric perspective, just out of nostalgia if nothing else. It's the type of game I could see being played as part of a school assignment: a straightforward and educational look at a career many would be too squeamish to acknowledge or examine too closely. I can't say I handle death particularly well either, but a game like this does much to alleviate the fear and trepidation of knowing me and my loved ones will only exist on this planet for an extremely limited amount of time. Certainly puts playing six 2017 games in one month into stark perspective.

Ranking: C. (While it handles the same subject matter as Rakuen, it's not quite as emotionally resonant nor as involved gameplay-wise so I'm thinking of dropping it a few places underneath. Games like A Mortician's Tale are certainly important to the medium though: offering a necessary perspective on the death industry that's both informative and emotionally intelligent, highlighting challenges that arise from preparing the bodies to doing right by the deceased and their family.)

Log in to comment