Sports Radio in Final Fantasy X

By thatpinguino 12 Comments

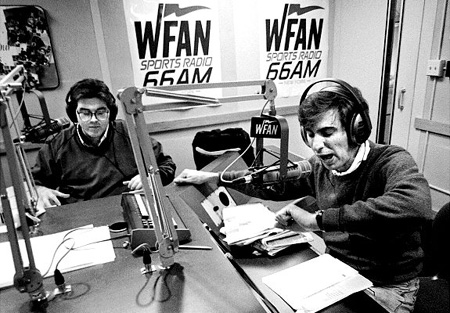

I am a New Yorker and my father is a sports fan. Growing up, that meant that every car ride was accompanied by WFAN and the ubiquitous talk radio team of Mike and the Mad Dog. The calm, deep, and authoritative voice of Mike Francesa mixed perfectly with the shrill and frantic energy of Chris “Mad Dog” Russo. These two hosts’ bickering about the sports events of the moment were the soundtrack to much of my childhood, and ingrained in me a strong appreciation for talk radio. For hours the two would go back and forth about the Mets, Yankees, Giants, Jets, and maybe they would even acknowledge the existence of the Islanders or Bills, if it was a slow news day. Years of exposure to their program has led to me associating sports talk radio with many fond memories, and as a result there are few things that say, “I’m home,” quite like Mike Francesa berating some listener about the Knicks salary cap situation. Sports talk radio is that little bit of milieu that always resonates with me. Whenever I get to a new town, a good sports radio show can both make me nostalgic for Mike and the Mad Dog and make me feel like I am a little bit closer to home. So it was quite surprising to hear Zanarkand sports radio in the opening minutes of Final Fantasy X.

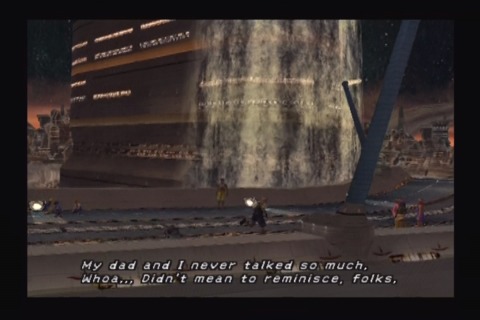

Final Fantasy X begins in a city called Zanarkand with a blitz-ball game (an underwater combination of American football and European fútbol). The main protagonist of the game, Tidus, is the star blitz-baller (blitz-ballsman? Blitz-ballist?) of the Zanarkand Abes. At the game’s outset, he is on his way to play in the Jecht memorial cup. This ceremonial tournament is played to remember Jecht, Tidus’s father, who disappeared 10 years before the events of the game. All of this setup exposition is conveyed, not through a wall of text or a narrator, but through a Zanarkand sports radio broadcast which plays as you control Tidus on his way to the game. As you run through the sprawling city streets of Zanarkand, an initially somber radio host reminisces about the day Jecht went missing, saying,

I was in a coffee shop, running away from home when I heard the news. Our hero, Jecht, gone. Vanished into thin air! My dad must have been his biggest fan. I knew how sad he'd be. Heck, we all were that day. 'Zanar,' I says to myself.' What are you thinking?' I went running straight back home. We sat up talking 'bout Jecht all night. My dad and I never talked so much.

The game told me about the culture of the Zanarkand in a way that my New York state of mind could understand. The game presents Tidus’s father’s disappearance as an earth-shattering, life-changing event for the people of the city, like Lou Gehrig’s famous speech or any number of uniting sports moments. The impact of Jecht’s disappearance is conveyed through the anecdote of an ordinary sports announcer. I found the game’s opening brought me back to car rides with my dad, just as Zanar used Jecht’s disappearance to reconnect with his father. Jecht’s disappearance is framed as a sports tragedy first, and a magical happening second.

I don’t know of many pure fantasy games that utilize the minutia of modern-day sports culture quite like Final Fantasy X does, but I wish there were more of them. The little touch of adding sports fanaticism to an otherwise fantastical world did a lot to ground the world of Spira for me. It gave me a bit of shorthand to understand the people of Spira; if they have sports radio they can’t be that different. I wonder what Mike and the Mad Dog would have to say about Titus’s team leadership or my work as the general manager of the Besaid Auroks.

Log in to comment